The Branson Pilgrim

All photographs from Branson, Missouri, February and May 2021, by Rafil Kroll-Zaidi for Harper’s Magazine © The artist

The Branson Pilgrim

i. NEMESIS

In 2010, I was forwarded a letter this magazine received in which the writer complained about an ungrammatical sentence. As both the author of the offending sentence and—in the one real, full-time job I’ve ever held—something like this publication’s usage authority, I felt obliged to reply, and explained that the sentence in question (“five white tigers in a Chinese zoo had become fearful of the live chickens offered them as food”) was definitely kosher, though I understood it sounded a little archaic not to say “offered to them.” This was not enough for my correspondent.

His name was Steven. He had a personal website that featured a range of his writing, which was consistent foremost in its infectious sui generis infelicities—whether fiction (“Bologna, he thought, but to him, it wasn’t just bologna; it was his crown of thorns”), spec ads for nonexistent restaurants (“Backyard Place. . . . We won’t put any fancy in your pants; just the tough stuff”), service articles published on how-to websites (“For the best chance of success, the single man should press his pants”), or even his bio (“In April of 2007 I became married to my wife”). Steven had finished college at twenty-five, putting himself through Missouri State by prep-cooking at the Olive Garden in the nearby town of Branson. By the time he wrote to me, the year after he graduated, his assumptions about the opportunities his education entitled him to seemed to have been let down. He expressed a frustrated aspiration to a world of letters where everyone who couldn’t get by on artistic endeavors could with ease swing handsomely paid hackery, on the long-dead model of the writer who supports his literary indulgences by deigning to pick up Hollywood rewrites or ad copy.

This all endeared Steven to me (granted, I was and remain a person with abnormal interests). He wasn’t the typical boring scold. His mind worked in peculiar ways, and his prose seemed always in thrall to stylistic principles that did not exist for anyone else. So I was happy to engage with him as he returned to me week after week bearing passionately nonsensical arguments for why I was wrong, and when he eventually named the authority he would defer to in the matter (“A Writer’s Resource . . . the grammar curriculum of accredited universities in Missouri”), I wrote to its authors (three busy women who were university presidents and the like), asking them to draft a letter in support of my sentence, which they did. I forwarded the letter to Steven but didn’t hear back.

Long after any hope of a reply had died, I still waited eagerly for any new work of Steven’s to appear. I had come to notice a prickliness toward his adoptive hometown, its hokeyness and its conservatism; in a familiar-feeling development, he picked a fight with the local newspaper and its op-ed crank: “It’s not simply that there are spelling and grammatical errors in every issue, but more so that you allow ‘The Old Seagull’ to publish racist rants.” I sensed that Steven was spontaneously espousing progressive values less than he was bridling at the values that prevailed around him. For Branson, I had come to gather—beloved and famous among some of our countrymen but unknown to many others—was no ordinary American town. It was, if anything, the inverse of the limpid paradise Steven imagined my world to be (and that I wished it were).

With two years gone by, I found myself still curious enough about this man and this place that rankled him that I decided to pay them a visit. So, at the Starbucks across from the nicer shopping center, the man and I met. Considering that I hadn’t offered him any kind of sensible explanation for why we were doing so, we got on well enough. And I found much besides Steven to fill my days that week—and keep me coming back to visit a number of times over the course of a decade. I confirmed my suspicion that Steven’s writing had underplayed Branson’s strangeness and appeal; if he was not to be my Virgil, he had at least been the Charon who brought me over the White River. And if I was lucky, I thought, the town might have some powerful thing to reveal to me about this nation, a half-superstitious hope that was buoyed by my later watching, at the big-cat rescue outside town, dead chickens being fed to five unfearful white tigers.

Branson, Missouri, has long been a pilgrimage for a very particular Real America. For decades it has been a show town: shows that feature cornpone hillbilly humor, rhinestone-spangled kitsch and “The Star-Spangled Banner,” “The Battle Hymn of the Republic” defanged of its Yankee bite, Lincoln and Lee paired in imaginary fraternity on the wall of the men’s room, country ballads and gospel standards, all haunted by the righteous presence of Jesus and Reagan and our honored military veterans, who if they are in the audience should stand (just the vets, though if the other two are here with us tonight . . . ), and, bused in from every corner of our great nation, old white people—old white people and their parents. Several times I hear “There’s a one-hundred-four-year-old in the audience” or “There’s a one-hundred-eleven-year-old in the audience, and it’s her birthday,” yet never does the person respond, and I can’t tell whether some or all of these are deadpan bits wherein it’s suggested that the (super)centenarian has died. But even if you are “white” all the way back to before the Gospel reached your ancestors, if you tell me you’re the child of two college graduates, I will bet you money (anathema in this town) that you’d never really heard about Branson. As part of his book about the divergence between socially elite and working-class white Americans, the sociologist Charles Murray created a quiz you can take on PBS’s website that weighs your coastal bubble against your Heartland ballast, and when I answer that “Branson” brings to my mind this town ahead of Sir Richard, I get an extra drop-down question asking whether I have ever visited, and when I answer that in the affirmative—I mean, just look at my name and you can guess most of my other answers—it basically breaks the scoring algorithm.

This shibboleth, thanks to a cabal of knowing outsiders, sometimes finds its way into mainstream pop culture. The on-the-lam sequences of Gone Girl take place in this neck of the Ozarks, allowing Tyler Perry’s New York City lawyer to crack wise about a down-market Real Housewives of Branson. “This ain’t Branson, Missouri!” is how Danny Trejo’s turncoat gangster on Breaking Bad teases a DEA square for his white-bread rectitude. Very, very rarely you’ll come across an appreciative recommendation in a place like the Washington Post or Forbes. Until Steven entered my life, all I knew of Branson came from a scene in a 1996 episode of The Simpsons in which four of the fourth-grade boys wind up there in the course of an illicit road trip; the class bully, Nelson, insists they stop so that he can see Andy Williams in concert, and is brought to the verge of tears by the second-encore performance of “Moon River.”

The town, greatly loved or gently maligned, manifests as a dense, gorgeous vision of American strip-mall wasteland unfolding over some six sinuous miles of neon and LEDs tracing West 76 Country Boulevard, populated by the names and faces in lights of familiar departed stars and unfamiliar living ones, cozy motels and vast cafeterias of tasteless food that wind down at six o’clock, marquees signaling that certain itinerant performers have jumped from one venue to another, or that set lists cast in amber are right where they’ve been for decades, third- and fourth-string offerings pulled in by the gravity of the rest (hole-in-the-wall acts playing to a dozen audience members in banquet chairs, ungainly hoards of memorabilia advertised as “museums”), starting in the old downtown and ending where the buildings abruptly thin out and the road rises twisting among bluffs above wooded hills, toward Silver Dollar City, an 1880s-pioneer-themed amusement park.

The park sits atop one of Branson’s original but now minor attractions, a colossal cave that has been welcoming visitors since the 1890s. Other early tourists came for a tepid lake. But what made Branson’s name was the enormously best-selling, evangelically flavored 1907 novel The Shepherd of the Hills, by Harold Bell Wright, which is set around the town. Half a century later, just as Silver Dollar City opened and the Army Corps of Engineers dammed the White River to create miles of prime boating and fishing waters, a play based on Wright’s novel, running to this day, debuted.

In the book and the equally tedious play, an old erstwhile Chicagoan lives harmoniously among the proud, simple mountain folk, bedeviled by bushwhacking anarchy and burdened by the secret shame that the fine-talking Big City artist who knocked up a local girl then left her to die of a broken heart was his son. The original cast members of Shepherd helped set up some livelier entertainments, and by the Eighties Branson began to pull in outside names for extended residencies or to settle—some of them with national profiles, most of them country and/or western, but all G-rated, clean enough for (if not alumni of) Sixties broadcast TV. New performers who hadn’t heard of Branson were pitched on “Vegas without the gambling”; Homer Simpson’s description is “Vegas if it were run by Ned Flanders”; a 1991 60 Minutes segment said that the town’s four-million-odd annual visitors came in the faith that “they will never hear a dirty word or see a bare bosom.”

There was allure beyond negation. Branson’s geo-cultural attributes—not quite the Midwest or the South or Appalachia yet also all three; a region of old European settlement but also westward expansion; perched above whatever modest altitude turned the soil to junk and predestined the land for poor Scots-Irish pastoralists; in a slave state with the largest anti-Union guerrilla campaign of the Civil War but little practical use for slavery—invite an unmistakable imaginative allegiance. This is the aspiration and the apparition that the novelist Joseph O’Neill has termed Primordial America, the “buried, residual homeland—the patria that would be exposed if the USA were to dissolve.” “Wherever they hail from,” 60 Minutes’ Morley Safer went on, “they feel they are the Heartland.” No matter the innate fuzziness, Real America in this formula is white, Christian, and prizes independence from the state. It is atavistic, not reactionary.

A pasture with such a flock seemed to me, a decade ago, more resilient against change than the unfolding years would prove—than even the years before my arrival should already have hinted. And while Branson’s recent evolution has taken many forms, one in which both stasis and progress may be observed is in the town’s conspicuous population of dinosaurs. I have found dinosaurs in abundance at, naturally, the Dinosaur Museum (a dimly lit office building whose creatures have crashed through its interior walls), but also on happenstance patches of pea gravel, and on mini-golf courses, and, tellingly, at interactive learning attractions—now that other, still extant megafauna (human children) have become as important as senior citizens to the town’s economy. The older crowd who keep the faith, meanwhile, can still get their fix at the Creation Experience Museum a few miles north of town, where all the dinosaurs, fiberglass models as well as pictorial fantasias in the bowels of the Ark and in the seas and skies on the Fifth Day, defiantly dangle the forbidden fruit of evolutionary theory. The statues are clearly from a professional theme-park shop, but most of the museum, like a lovingly handmade Halloween costume at architectural scale, exhibits a winsome amateurism that persists in pockets of Branson but whose age is drawing to a close.

The museum’s founder, Rod Butterworth, a wee English transplant, points me to one of his “politically incorrect” paintings, of a bird and a brontosaurus in anachronistic synchrony. Dinosaurs and humans cohabited, he tells me, until a time just out of mind, the era of New World exploration.

Maybe cultural change seems different if you believe geologic time can be reckoned in human lives, if the strata of grayish-green thin-bedded crinoidal limestone and finely crystalline Cotter dolomite blasted visible in the highway cuts around the museum came into being a mere eighty Dolly Partons ago.

ii. mascot

As an Eighties baby, I am barely old enough to remember Yakov Smirnoff in his original iteration—as a genial, beaming, against-type import from the dour Evil Empire whose shtick was bemused wonder at restive, bountiful America. He had roles on Night Court and in movies starring A-listers like Robin Williams, Tom Hanks, Meryl Streep, and Richard Pryor, plus seven Johnny Carson appearances and many TV commercials and a single season of his own sitcom. He hosted the 1988 White House Correspondents’ Dinner. His signature not-quite-punch line is “What a country!” But his enduring contribution to American culture has been the “in America” vs. “in Russia” inversion joke, which he made famous in a Miller Lite commercial: “In America . . . you can always find a party! In Russia, the Party always finds you.”

“Jay Leno started making fun of this,” Yakov tells me, the first time I meet him. “When he would see me, he would say, ‘Yakov! In America, you watch TV; in Russia, TV watches you!’ And those made sense. But ‘in America, you drive the car; in Russia, car drives you,’ that makes no sense!” I sheepishly offer a Yakovian joke that I once made up, and which he receives with patient magnanimity. The form has been endlessly riffed on, often (and more and more as time passes) by people who have no knowledge of its inventor or else attribute the ersatz absurdist specimens to him. “They were so easy to do that the kids still think that I—on the Wikipedia, that’s sort of what I’m famous for.”

Once his original notoriety dissolved in sync with America’s great geopolitical foe, Yakov was left looking for a second act, and in the early Nineties, on a tip from Willie Nelson, he found his way to Branson, where few patrons followed his career before the fall. “So, I have this line in the show,” he tells me, “ ‘I started looking for a place where they did not know that the Soviet Union had collapsed.’ ”

I affirm that it is a good joke.

“It’s a great joke, but the point is, it’s true. They didn’t really care here.”

He started playing to audiences that numbered in the teens, then, as word spread through the grapevine of Branson’s die-hard repeat visitors and the crowds grew, he built his own theater, a two-thousand-seat brick-clad hulk on eighteen acres commanding the heights above U.S. Route 65 at the eastern edge of town, welcoming weary travelers to Branson and appropriately resembling a highway rest stop. The lobby walls are dense with memorabilia, such as a self-portrait that Yakov, who is trained in the visual arts, painted of himself as (I think?) Jesus, a signed headshot of (unmistakably) George W. Bush, and photos of Yakov with basically everybody—LeAnn Rimes, Andy Williams, Arnold Schwarzenegger, Nancy Kerrigan, Magic Johnson (at a Bush–Cheney inauguration). Out front, a gigantic animatronic caricature of Yakov’s head, wearing an ushanka, unblinkingly cycles its lower lip to a loop of one-liners that all self-reflexively concern the bigness of the talking head (“I blew up my computer trying to get onto Facebook”), followed by Yakov’s gasping laugh, which Jerry Seinfeld once compared to the sound of rusty nails being pulled out of old floorboards.

The head must postdate the theater by some years, since it captures the crow’s-feet that have softly settled into Yakov’s face and which complement the flinty, dyed look and sharp wardrobe of a veteran pleasure-boat magician. I ask whether the shift to Branson was as simple as hitting repeat on the Eighties, or whether the transition from national recognition to regional cash cow was tricky, playing to such a straitlaced crowd. “My material was always clean,” he says, “so what resonated with Branson audiences was that I was clean, I was family-oriented, and I was patriotic.” Without these necessities, others who might have seemed closer to the town’s stereotypes had tried making the move here and failed. Take Merle Haggard, an established country-and-western star (and, like Yakov, a personal darling of Reagan’s) who fizzled because he was too salty and insufficiently deferential to evangelical mores. Andy Williams, by contrast, wasn’t the least bit country, but was able to win over the Branson audience with his accessible yesteryear gentility, and by making the right noises about his values and allegiances and including the obligatory white gospel.

The arc of Yakov’s show, which has several versions (Christmas, dinner-and-a-, etc.), follows him from his Soviet childhood to his experience of arriving in America with his parents at twenty-six (the unadorned hell of Cleveland, the stirring bustle of New York), to his professional success and his brushes with the Gipper, for whom he wrote jokes to punch up speeches that dinged the Reds. There are other Forrest Gumpian anecdotes of his cameos in world-historical events, and extended digressions in which he waxes sentimental, answers audience questions, and ponders the dynamics of romantic relationships. The meat consists, as ever, of ESL wordplay gags.

To gauge Yakov by the orthodox Branson standard—the country-variety jubilee—one has to write off the expected musical repertoire (the Oak Ridge Boys and the Collingsworth Family, gospel and the careful concessions to rock classics and newer pop-country) and look to the town’s one truly indigenous entertainment offering: the hillbilly. Back when The Shepherd of the Hills was still the biggest driver of Branson tourism, enterprising locals refashioned themselves to fit the mold of the novel’s characters, creating a living diorama to cater to visitors eager for the bucolic authenticity of the Ozarks. Later, the Clampett family of The Beverly Hillbillies, hailing from this corner of the Ozarks, returned “home” for five episodes filmed at Silver Dollar City. Today, the variety shows’ wise-clown hayseeds (overalls, prosthetic teeth, silly hats, no shoes) are the ones who get all the good lines, whose material is distinctive in its political sensibility and cultural hobbyhorses.

Yakov, too, is a naïf who asks the right questions and gets wrong-footed by homophones and consumer modernity, and he knows he is cut from the same cloth: in years past, he would as part of his show debarrass himself of a Cossack costume to reveal cutoff overalls. And though he’s often gentler with his touch, he serves up much of the same material: early-Nineties toilet humor about flatulence and Taco Bell, American Indians and their casinos, the existence of Spanish-speaking immigrants. “They didn’t speak English,” he says of the landlords he and his newly arrived family had in 1977. “They were from Ah-ree-zoh-nah.” He doesn’t refresh his references for every presidential administration, preferring to lionize Reagan than to disparage others, but nor does he leave Obama alone entirely: “I wasn’t born in America. Not even in Ha-wai-ee.” He proposes sending Russia “ambitious, aggressive people from America that we can spare. Like personal-injury attorneys. Give them the Kardashian family. And Rosie O’Donnell.”

Yakov fit his act to the frame of Branson not through any special Cold War frisson but as an unlikely figure of anti-modern nostalgia. “How did it get so complicated?” asks a yokel in Pierce Arrow, the most red-blooded of the variety ensembles I see. “I mean, it wasn’t like this when we was kids, was it? . . . But now they’re changing all the stories we growed up with.” Yet the hillbilly is an unfallen, untrammeled white man who remains free, in part, because he knows no better, whereas Yakov is acutely conscious of and vocally grateful for the freedom he has achieved by leaving the privation and primitivism of “Russia” and coming to America. He closes one version of the show by leading the Statue of Liberty in a waltz across the stage, introducing us to what he calls “the best moment of my life”: Independence Day 1986, when he was administered the Oath of Allegiance by Chief Justice Burger on Ellis Island. (Across the harbor a quarter century later, on the first anniversary of 9/11, Yakov moved mountains—expensively, anonymously—to hang a huge banner bearing his pseudo-Impressionist painting of Lady Liberty over the World Trade Center site.) This enthusiasm still feels radiant decades and thousands of shows into the grind. Its energy can revive the audience’s ancestral European-immigrant selves.

Yakov’s being a foreigner is not a hurdle to his winning over the Branson audience—it is the very means by which he does it. (By and large, the old white folks I visit with in Branson, like true Eighties Republicans, harbor an almost excessive love of immigrants, particularly the bootstrapping, legally entering, English-speaking kind, and I benefit from a spillover of this goodwill. My actual background—half-American, born and partly raised abroad, slipping into a slight Texas accent in a place like this—is too niche to bother correcting such misperceptions.) Yakov once told me that comedy in the Old Country was more like vaudeville than stand-up, and I came to realize that his show re-creates certain strains of American vaudeville: greenhorn immigrant characters represented new additions to the prosperous, assimilated ranks of its working- and middle-class audiences and dramatized the melting pot. While the physical markers of one’s ancestry would endure, one’s heart and mind could be inspiringly directed toward a new allegiance. Yakov cribs an unattributed Reagan line on this American virtue, which his website celebrates in an oddly overdetermined formulation: “Only in America does a Japanese, a Chinese, and a Russian own a theater in the middle of the Ozarks!” (The Chinese being a troupe of acrobats, and the Japanese being the fiddle player Shoji Tabuchi, another ageless—if now deceased—septuagenarian and consummate performer of immigrant patriotism.)

But if there is any group about whom the public at large have failed to buy such happy-sounding generalizations of new loyalties overcoming old differences, it is, immemorially, the Jews. So Yakov is understandably shy about this aspect of his background. When I ask directly whether his family got out on the special exit visas for Soviet Jews, he answers, “It’s because Jimmy Carter made a wheat deal with the Russians,” which is to say, Yes.

The concept of “civil religion” can mean the ideology of American history and purpose raised to the level of spiritual faith (Constitution-worship and the like), or else a fusion of national purpose with Christian religious purpose, running the gamut from progressive, service-oriented Christianity to Christian nationalism, with its center somewhere near the evangelical sense that America’s founding vision, freedoms, and unique character are essentially Christian, “one nation under God,” the providential rather than the experimental aspect in Tocqueville’s analysis. Now and again in Branson I encounter explicit civil-religious dogma, as when the Pierce Arrow performers ask veterans to stand, announcing, “It is your service that allows us to be free. And like our Lord and Savior, without your sacrifice we would have nothing.” Yakov is certainly an America worshipper, and it is for those who like a heaping side of church with their state that he pulls together a winning recipe: by turning naturalization into a drama of salvation, he has roundabout created one of the more evangelical acts in town, one that can make the native-born patriot jealous. If you are American by birth, you cannot have the experience of being saved twice.

iii. mercy mild

One wintry night after Shoji Tabuchi’s Christmas show, outside the brutish theater that by darkness is transformed into a marvel of South Beach neon and inside of which you’ll find not only a stage of Wagnerian scale on which the fiddlesome star has lately emerged in a sequined tailcoat from the belly of an enormous penguin but also the luxurious men’s facilities that were awarded Cintas America’s Best Restroom ® in 2009, I happen upon three lost souls in the parking lot. They are little old ladies (actually one is tall, but the littlest is maybe four foot five) here on a motor-coach tour from Salt Lake City, and they have missed said motor coach back to where they are staying (or really, the motor coach has missed them). I offer them a ride, and they accept.

The ladies are seasoned Branson visitors; the tiny one was here not five months ago with her husband, and Shoji was good then, she says, but tonight, we all agree, he was great. These gals like the Osmond Brothers and the Lennon Sisters and Mickey Gilley, though he hasn’t been the same since he was crushed by a love seat. We weave about, not knowing quite where we are headed but following the light of yonder outlet mall that they know their place is just behind. We realize that earlier in the day we all attended the same caroling performance on Showboat Branson Belle, a paddle wheeler that didn’t leave the dock and on which “dinner” was served at such an ungodly Christian hour that the postprandial coffee appeared at 3:59 pm, so they are about ready to fall asleep as I drop them off, and the tiny one, who thinks my name is Rascal, tries to tip me.

Barely more motile than the Belle is the Christmas train, which is a dressed-up and child-friendly excursion of the regular old worse-for-wear sightseeing train that trundles some miles out of town, over ravines where the owner of an occasional haphazardly stationed RV stokes an open fire, till it reaches, just over the Arkansas border, a trestle bridge to nowhere. Except at Christmastime it trundles back and forth through built-up parts of town, taking us through dim, spectral displays of string lights set at uncertain distances, until it is beset by some kind of hijacking elf or gremlin, rather inconsistent with the narrative scaffolding for our journey, which is licensed from The Polar Express. (The interloper, it turns out, is actually billed as a “hobo,” with the authentic look of one of the local meth heads, who I suppose have supplanted the hillbillies of old and whom I have seen causing no end of trouble at a free local stand-up show.) I have not paid attention to Christmas music in a long time, so it is in Branson that I learn that “Let It Go” from Frozen is now holiday canon, as is, for churchier folks, “Mary, Did You Know?,” a 1991 song that has become widely known because of an a cappella pop cover.

I have likewise not paid much attention to church since I was required to attend daily services in school, but I figure what the heaven, it would be nice to enjoy some atmospheric music at this time of year, and so turn up on Sunday morning at Branson Church of Christ. Unfortunately, I have forgotten that the Church of Christ’s notable characteristic is that they disapprove of both using musical instruments in services and, for the most part, celebrating Christmas. The church was formed through a great doctrinal schism over said instruments, in which, the preacher tells us, the “apostate brethren” stole 90 percent of church properties. So now, along with many other out-of-towners also not of this denomination, I am treated to some fiery warnings against innovation and zero Christmas spirit (though the church apparently does a Secret Santa). It is all too much, or too little, so afterward I go to Don’t Stop Believin’, a Journey tribute whose ideological precepts I am relieved to discover I have anticipated correctly.

Another wintry afternoon, at the Irish Tenors and Celtic Ladies holiday show, which adds a heady Emerald Isle drizzle to the already confectionary sentimentality of American Christmas, I encounter a man who looks and talks and dresses like Habitat-era-casual Jimmy Carter (plus forty pounds and a permanent case of hiccups), whose name tag identifies him as david, here with a seniors’ bus tour from Tennessee. He keeps mysteriously exclaiming, after I’ve come out of the bathroom into the lobby at intermission, “I couldn’t see you in there awhile!” to which I reply that, yes, one does enter the stalls after waiting one’s turn—as we both just did!—and thereby becomes invisible to those without, until after several rounds of this I realize that his mood is not indicative (concerned) but interrogative (horny).

Yakov has a joke for this: “Men, we don’t talk in the bathroom. . . . When you hear one guy say to another guy, ’Nice Wranglers,’ there’s going to be a fight! Or you’re in the wrong bathroom.” This is the wrong bathroom for David’s designs, not least because there is a line of fogies out the door making liberal use of the diabetes-sharps disposal bin. I politely decline his decorous cruising, though this does not dissuade him. Years on, I retain a mild curiosity as to whether he persisted in his hopeful lurking and waited around after the show for me, which is to say for nothing, and maybe missed his bus, and whether he has lately taken the bus he cannot miss, which is to say, not the one that was meant to carry him back to Tennessee, but the great motor coach that brings us all home.

iv. the merchant of memphis

Many of the shows have merchandise on offer: Guatemalan blessing dolls in one-, two-, and three-inch sizes for $1, $2, and $3, respectively; “accurate books on America’s Christian history,” which is being erased; a harmonica; a doll of Cecil the hillbilly clown; cinnamon-glazed almonds and pecans; the display model at your seat for only $5; a $45 value for $25; refillable mugs (“You can bring it back thirty times over the next five years and they will fill it up every single time”); skunk and raccoon puppets; a vase; “not your ordinary pot holders”; DVDs of the show you just saw for $20; a studio-recorded CD for $20, “not counting tax—tax is another two dollars, but Jerry’s going to pay the tax, and he’s going to autograph it.”

Jerry Presley’s offer is the oddest one I come across: a CD of an Elvis tribute artist (“impersonator” borders on a term of abuse), when the whole point is the live show, but perhaps you buy the disc to rekindle the memory rather than to delight the living ear. Jerry is kin not to the Presleys of Presleys’ Country Jubilee, one of the old family variety shows, but to Elvis himself, by way of a kissing-cousins family tree that makes them second cousins once removed as well as fifth cousins once removed.

Jerry is short and solidly built, with loud blue eyes and brilliant white teeth and a bootblacked pompadour, and when he meets me, off the clock and out of bedazzled jumpsuit, he wears hiking boots and mom jeans. When he is onstage, his charm is avuncular rather than sexual, the transubstantiation of legendary manna into comfort food. “Who would like a kiss from Elvis?” his pitchman asks the crowd of three dozen or so, fittingly on Requests Night. A man raises his hand. “You’ll get a little sugar, a fist bump, a kiss on the forehead.” Any ladies who want them get little silk scarves draped round their necks by Jerry, and most everyone sticks around later for an autograph or a photo.

The scarves are mass-produced and available for purchase, without ceremony, in the lobby, but Jerry is also a connoisseur of auratic knickknacks, only some of which are for sale. He tries but fails to locate for me an old address book that belonged to Elvis’s father, Vernon, in which is recorded the birth and death of Jessie Garon Presley, Elvis’s stillborn twin. Jerry is able to produce some pine cones from Elvis’s yard. “Forty-three years old!” And after the sale of Vernon’s former house, full of all manner of furnishings that had been emptied out of Graceland after Elvis died, Jerry tells me, he went in and took everything, two twenty-six-foot U-Hauls’ worth.

He had been one of the original Elvis tributaries, starting back in 1970, though without the explicit sanction of his cousin’s management; after a newspaper wrote about his act, the Colonel sent Jerry a cease-and-desist letter, and he tore it up in embarrassment. He didn’t quit, though, and when he got to Branson, in 1985, his was the first Elvis show, indeed, the first rock and roll show, and he set about building a theater, the King’s Mansion, with a façade done up to look like Graceland. But a mere four years later, he got an offer on the building, sold it, and went touring with some of Elvis’s backup singers, the Jordanaires, till finally winding his way, in 2013, back to Branson and then to the God and Country Theater. The name isn’t Jerry’s, but both are things Jerry holds in ultimate esteem, along with Elvis: “I think the Lord manufactured Elvis Himself and sent him down here for a reason, and we might not know what that reason is yet.”

Among the bulk-acquired consubstantial relics was an eighteen-foot roll of Graceland carpet, which Jerry, in the manner typical of the high-functioning hoarder-speculators I’ve met, started selling.

“I put an ad in Variety magazine. ‘I’m gonna cut it into one-inch squares and advertise it, make one and a half million dollars.’ So—what was the paper that was kind of the slut paper?”

The National Enquirer?

“The National Enquirer. So they called me a ‘carpetbagger.’ ”

Jerry backed off, but his embarrassment is not especially resilient. “I do have a lot of furniture that came out of Graceland. I’m going to cut some of that into one-inch squares, and they can call me whatever they want.”1

If there is one misstep he very obviously regrets, it’s his timing. “I left too early and came back too late,” he says, with rote pithiness. Jerry means his being away from Branson for the Nineties. Branson’s performers, in interviews during the George H. W. Bush and first Clinton Administrations, sound equal parts smug and bewildered at the teeming theaters and easy money. On the 60 Minutes feature that both documented and helped fuel the boom, Waylon Jennings, quoting Mel Tillis, repeated a familiar quip: “Will the last one to leave Nashville for Branson please turn out the light?” In 1983, Roy Clark, of Hee Haw and The Tonight Show, had opened his own theater; Boxcar Willie and Tony Orlando and (on a bit of a whim) Andy Williams had followed suit. Wayne Newton was lured in from Vegas. Willie Nelson and Loretta Lynn and a variety pack of Lennon Sisters and Osmonds (not Donny or Marie, though) were among those who turned up for a few months or for the rest of their lives. Strange ambitions were roused: Johnny and June Carter Cash tried opening Cash Country, a theater and theme park; Guns N’ Roses inquired about local dates.

“We”—and here Jerry is painfully absent from the plural—“used to get five thousand bus tours a year in the Nineties.” But competition was intense, and the demands of the “droves” of motor coaches were outpaced by the supply of “we.” Orlando and Newton’s co-branded theater, Talk of the T.O.W.N., was riven by squabbling over a bugged ficus, though Newton said the real story was Orlando’s inability to keep seats full—an anxiety shared by many of the Nashville and Vegas transplants. Stars started getting spooked and bowing out.

Even with sustained success, Jerry tells me, the bigger performers “who had wanted to get off the road saw it was more work coming to Branson doing six nights a week than touring the country, so they all started leaving.” By the time Jerry settled back in, not a single one of the old household names was still resident and aboveground. As quickly as that, Branson’s stars had dimmed back toward local and often familial renown—Haygoods, Duttons, Hugheses, Presleys—while the town had also been evolving into something beyond.

“I entertained the idea one time of taking my smaller theater and turning it into a competitive gaming room,” he tells me. “Just whatever games these kids play—computers, that’s what they seem to be interested in. Gotta do what the people like, whether you like it or not.”

Even the stable, perennial variety shows make gradual adjustments—incorporating American Idol–style solos and newer Top 40 hits; adopting, widely if belatedly, the glam-country look that emanated from Travolta’s Urban Cowboy; sometimes refreshing their jokes (Obama, Bieber) and sometimes not (Clinton, Taco Bell). The tribute bands themselves, Jerry notes, have been refreshed. “We’ve got Chicago starting, Fleetwood Mac, Three Dog Night, Temptations . . . ” Which is to say, the baby boomer repertoire has finally filled out. Many visitors want to engage with the music of their youth (more than in the Eighties, when the performers and the music were actually of a more recent vintage). Nostalgia, in both the cultural-myth sense (something like big-tent small-c conservatism) and the concrete experiential sense (in our individual and then collective memories), is in an endless process of updating and replacement.

“Elvis is like an heirloom, he’s just handed down from one generation to another,” Jerry says. “Back then, if Mom and Dad liked Elvis, that’s what the kids listened to, so those kids are in their sixties and seventies, and they have their own kids, and even them, they grew up listening to Elvis.”

So Jerry should be relatively insulated against the turnover of various nostalgia-mediated tastes. The fact that I was the only person under fifty in his crowd speaks less to the King’s everlasting appeal, or any lack of it, and more to a different force transforming Branson. The town has long sold itself as “family-friendly,” which was another way of saying showbiz “clean” and therefore safe for old people as well as their parents. But after the stage-show bubble burst in the Nineties, there came a rapid diversification of offerings, in an effort—part organic and part central planning—to lure “families,” in the nuclear sense, to spread the appeal more widely.2

The resulting pivot toward outdoor rides and activities as well as indoor amusements, Jerry grants, wasn’t (as some grumble) a tragic betrayal of the stage entertainment that “built Branson” but a rational anticipation of an inevitable trend: “the people who like music shows are fewer and farther between,” even as visitor numbers are now twice what they were thirty years ago.

Today’s typical teenager, according to Jerry, “if somebody calls him up and says, Hey we’re gettin’ a few of our friends together and we’re going to go see, I dunno, Lolly-Dolly whatever”—I assume Jerry’s gesturing at something like Lollapalooza but more Swiftian—“some outdoor concert that’s got ten thousand people, the kids can go out there and stand together and jump around and act silly, money’s not an object . . . a lot of kids today grew up playing TikToks and games. Even if we’re doin’ rap by the end, it’s just not what they grew up on.” Attrition isn’t just the same ship replaced piece by piece. It is also sea change.

v. see change

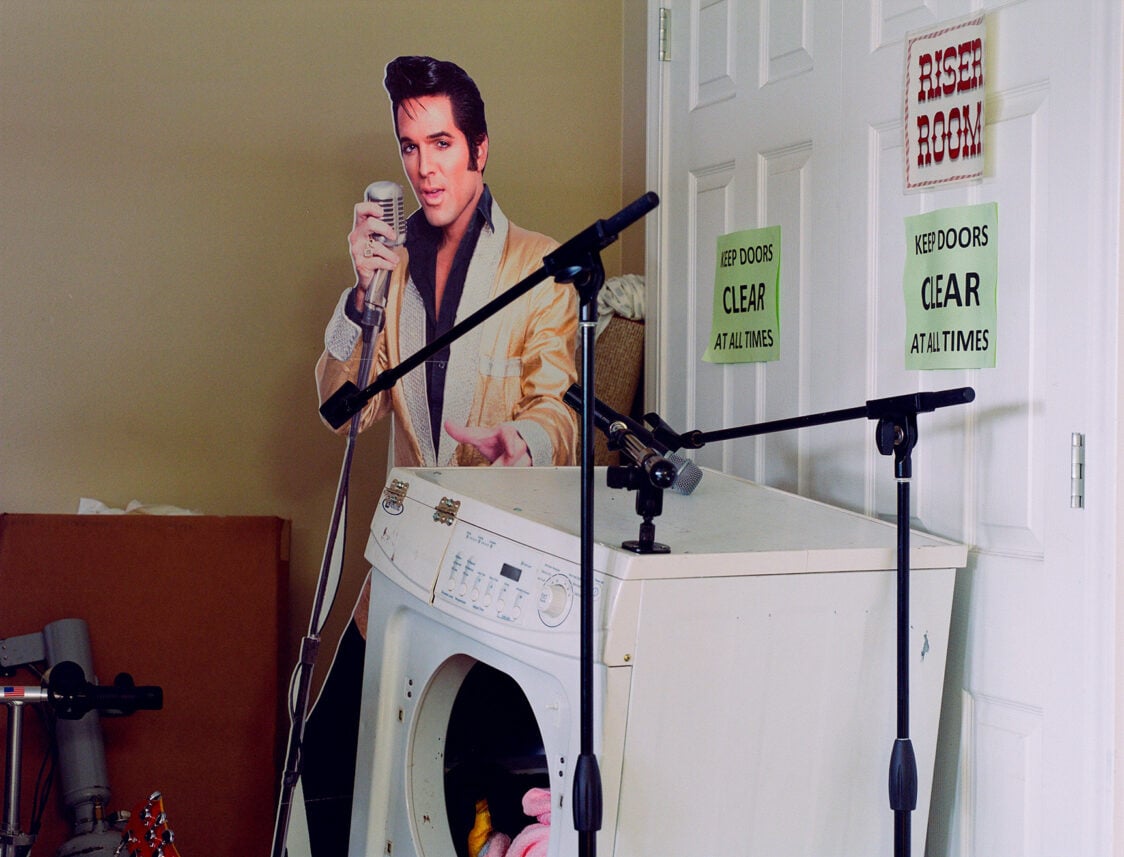

As I stand next to a disconnected washing machine hove up amid two forlorn mic stands and a life-size cardboard Elvis cutout, it dawns on me that this is not the King himself but Dean Z, the resident tribute artist at the Clay Cooper Theater, where Clay and I have stumbled upon each other in the basement and he is elaborating on one particularly visible difference between the years after he arrived—in 1986, at the age of sixteen, with an act called the Texas Gold Minors—and now.

“It used to be like, ‘A black person, in Branson! What’s he doin’ here?’ . . . I get it, twenty-five years ago this probably wasn’t a real appealing town to black folks. But now . . . I’ve asked everybody I work with, ‘Hey have you ever noticed how many black people—’ ‘—at the Wax Museum?’ It’s unbelievable! I can drive by every day and there’s a hundred black people in line! What”—these are excitable, Texas-bred vowels—“is the attraction to the Wax Museum?”

Though I’ve been coming for only a decade, my first visit squares with Clay’s memories: back in 2012, out of, let’s say, ten thousand visitors over five days, my biogeographic scorecard totaled, yes, zero black people, two woozily drunk Japanese women shouting heavily accented song requests at a couple of disintegrating Osmond brothers, and one Latino U.S. Navy vet on the sightseeing train whose conductor, I am as certain as one can be about such things, racially profiled me (probably not accurately) in deciding to search my handsome shoulder bag for contraband snacks.

Clay says a black friend told him, no hesitation, that the allure of the Hollywood Wax Museum is the presence of Michael Jackson. “So you’re a black family,” he mulls, “you got three kids, you drove down from St. Louis, and, like, can’t wait to go to that wax museum to see Michael Jackson. Like, that’s a draw?” He doesn’t buy that it could be so simple. He suggests I go find out for both our sakes.

Clay’s sales director, Pat, asks whether the theater ought to have its family-variety-show impressionist, Matt, perform his pretty serviceable Michael Jackson, and tweak some of their signage to say see michael jackson at the wax museum and also here live on stage! It’s not the worst idea, except maybe it is.

“Yeah, but then they get here and it’s a white guy acting like Michael Jackson,” Clay says, shaking his head. “That’s not good.”

As I skulk around outside the Wax Museum over a couple of days, nobody I ask about their visit—not the white couple from Cedar Rapids who think New England is its own country with an NFL franchise and are awed by the sublimity of mere hills; not the Turkish mom in hijab from Kansas City (doesn’t matter which one) with her nine-year-old son; nor any number of black folks in family units ranging in size from three to about fifteen—tells me they wanted to see Michael Jackson, or Oprah or Tupac or Elvis or Trump. In fact, nobody I ask about the Wax Museum names anything that brought them to the Wax Museum; they tend to answer by naming other things they have come to Branson for. Mini-golf. Go-karts and zip lines. The new aquarium. The butterfly palace. They tell me they’re looking forward to the outlet stores or the full-price retail down in the new riverfront arcade; they tell me they have been to the five-and-dime (presumably the spiffy, old-timey one, not the sad one that sells remaindered curly “IBM compatible” keyboard cords). They say they had a five-for-one ticket deal that also got them into the Castle of Chaos, that they are here just for the weekend, with their kids.

The two other places in America that have a Hollywood Wax Museum (Hollywood aside) are Pigeon Forge, Tennessee, and Myrtle Beach, South Carolina, both of which are stuffed full of off-the-shelf franchises that Branson, too, has acquired: Ripley’s Believe It or Not!, the Titanic Museum, WonderWorks, Dolly Parton’s Stampede. And it’s these budget-forgiving destinations (honorable mention to Wisconsin Dells) that Branson squares up against in its own marketing research. The draw is aggregate: family entertainment as commodity, completely deracinated.

Which has been a bigger and bigger part of Branson for years, like Jerry told me: The younger adults, who are here with and for their kids, have no interest in the town’s particular character and history and the package deal of country, Country, and Christ. They aren’t after a modest, more inviting version of Nashville or Vegas, or an updated country-greats repertory or a Christina Aguilera tribute (never mind that the wistful past does not yet exist for the children—it likely doesn’t for most of their parents). And so they have further tempered the ambitions of the live stage while pushing attractions to a franchise-level polish that children understand to be worth a car ride.

It’s not surprising this demographic is here in force now that it’s summer and school is letting out and plein air venues are attractive, yet I sense something else is different about this year’s summer crowd, beyond just—as a Branson worker named Ian says, confirming what Clay and my own two eyes have told me—that “black people never used to come here.”

Ian, a Belizean who since 2011 has been employed as a “houseman” at Grand Country, a huge hotel-cum-buffet (now also -cum-water-park for the kids), has the profile of an Assyrian warrior and, by certain confluences of imperialism, an accent like a Mexican SoCal bro, spends the work year dreaming of the beach and the congenial decency of life’s pace back in Belize, where he heads to spend the winter with his girlfriend and his three boys once Branson shuts down around Christmas.

Year after year, those grinding nine months, during which Ian works like crazy, picking up extra hours on landscaping jobs or whatever else it takes, have made him keenly attuned to wage fluctuations and the local housing market and federal benefit programs and, combined with a quiet, exacting curiosity, have given him a fingertip sensitivity for paying visitors as well as for the getting-by-but-only-barely Americans he lives and works among, the ones who switch out the steam trays and launder the linens. And this season, in 2021, he explains, the two groups basically converged. Or rather, people from the second category started pouring in as the first. The biggest thing to happen to American poverty in decades—the unemployment benefits and the Trump checks followed by the Biden checks, to use Ian’s terms—allowed these families to travel for the first time. “A lot of them, they’d never been on vacation before. You had kids who’d never seen an elevator. Big kids!”

That’s why so many of the museumgoers were first-timers in a town that usually relies on upwards of 80 percent repeat visitors in a given year. A barrier had come down, and black Americans, with a disproportionate share of poverty, were overrepresented in the new wave of commodity tourists who would otherwise have been hard to distinguish—visually—from the established throngs of regional, kid-dragged younger adults.

On the other hand, the black counterparts of Branson’s dominant white demographic (financially comfortable couples of Social Security age) still only rarely make the pilgrimage. Once in a while I’ve come across unicorns, like Harrison and Pat, of Dallas, whose five kids are grown and gone, who retired in their early fifties and look hardly older than that after a further decade and a half of easy living and recreational travel, which has included multiple trips to Branson. They are seated behind me at a performance by Reza, the town’s star magician, a half-Iranian South Dakotan who crosses Criss Angel goth with arid sarcasm and high-decibel guitar riffs; who as a child dragged his own parents down here; and whose stage show is one of just a few that draw new and old crowds.

Pat says she’d like to see, for her part, a little more . . . “The only thing I think they need to expand on, I know we’re in an environment . . . ” She is conscious of her phrasing. “They have a few R and B things.” Harrison understands but disagrees. “You gotta look at the clientele. The diversity of the crowd, based on whether they like country and western. The demographics, honey! The demographics is the main thing.” He hesitates for a moment, and I imagine his thought process matches mine: the demographics, if you include the broader change in age and sensibility, are what render the entire argument moot. “They have a lot of stuff for kids.”

I can’t probe the negative, so I can only assume other black Americans of similar circumstances to Harrison and Pat’s were long kept away, and still are, by Branson’s corn-bread whiteness or white-bread corniness. “This town,” Clay says, “it always had this cloud over it that we were just a bunch of racist hillbillies singing bluegrass music up in the mountains. I mean, that might have been true in the Sixties when there were two or three shows here and the Bald Knobbers running around like the KKK on their horses, but my God. That was a long time ago. Just like you can’t erase slavery, it happened, it’s part of history, you hope it never happens again.”

The Baldknobbers were one of those original few shows, and they are still going strong: Clay has substituted their earlier namesake, a local vigilante group who got recast as the hootin’, shootin’ villains of The Shepherd of the Hills. And though the original Bald Knobbers started as a Union-aligned militia and their hoods were more commedia dell’arte than KKK, the Klan’s national headquarters are indeed a stone’s throw from Branson, just across the border outside Harrison, Arkansas. And that Klan clan, I am told, are kin to the folks who run Branson’s Dixie Outfitters, whose sales of Confederate paraphernalia attracted community protests back in 2020 that, I am also told, helped lighten the pall Clay describes, showing any younger families who might have been mildly leery of the town that hearts and minds were in the right place, though plenty of Stars and Bars persisted. (Dolly Parton’s horsey dinner show was Dixie Stampede till 2018, when Dolly nixed the Dixie.)

“It is interesting to look out on the crowd on any given—I mean, we don’t get a lot of black folk here. But at my show, when we do, I have a tendency to, I can’t stop—watching them,” Clay says, in an awkward mood lately since his election to city council forced him to adopt public postures aside from his time-tested, affable sincerity. “And especially at the end when I talk about standing up for the police and the whole George Floyd thing. Uh. I’m not defending the cop, I’m saying what the cop did was terrible and George Floyd didn’t deserve it.”

As Ian and I stroll down the strip across from the Titanic Museum and the giant fork-impaled-meatball portico of Pasghetti’s, a young man in a lifted pickup full of young men leans out at us and shouts, “TRUMP!”

It’s the second catcall we’ve gotten in the past few minutes. “Not everybody can walk on the sidewalk here,” Ian says wryly. Then adds, with a weary authority, “Those are locals. People don’t come here to do that.”

I’d say he’s right. If you are one of the faithful who fondly recall “normal” conservatives in all their monstrous decency and await the return of Liz Cheney as the Twelfth Imam, you can surely find them here! They do not seem all that sore, as far as I can tell, that their Real America is becoming less particularly like itself as it welcomes other Real Americas. Or maybe some of them are and are staying away or just quietly expiring. As for the locals, in the years I’ve been coming I’ve seen only hints of something, shall we say, off-key, but it seems that as soon as there is more than one of us present—two, or tens of thousands; and whatever “us” is exactly—something gets too different, it constitutes some kind of irresistible provocation.

Ian introduces me to Ricardo, an actor and truck driver who was inspired to come down from his native Chicago with his fiancée and their three small children. Ricardo is a striking black man: short, powerful, and thickly built, with a shaved head, trim beard, and extensive tattoos, including palmettes that re-create his absent hairline, a map of Illinois’s interstate highways, a Mason’s square and compass, a portrait of his first love, who was murdered while on the phone with him, and an ankh under his right eye from his recent time in prison (he tells me he took a gun charge for a friend on parole, and while still under house arrest got a gig playing a bodyguard on the TV show Empire).

Ricardo has found Branson a charming place, one where you come not with friends to drink and raise hell but with family and significant others: “A love thing,” he calls it. He especially loves the Titanic Museum (the movie, too) and the boat rides on the lake. “It’s different,” he says. “It’s got mountains and hills, good food. I love the Ozarks!”

I have all my camera equipment with me to make the photos to accompany this article, and I offer to take some pictures of Ricardo and family, just so they can use them for Christmas or whatever. They are pleased with the idea and get set up on the cinder-block wall of a planting bed in the parking lot of Ian’s extended-stay, where the land slopes sharply down and away from the strip into an oblivion of low oak forest, the five-year-old boy making goofy faces for too many frames, Ian trying to coax him into behaving and his infant sister into smiling. A late-model SUV floats by, and a young blond woman leaning slightly out the passenger window calls to Ricardo in a rising-falling salutatory singsong, “Nigger!”

Ricardo calls back, “White girl!,” a slight break in his voice. His restraint surprises me only momentarily. He is with his kids and doesn’t want to make things uglier.

“White girrrl,” his son sings to no one in particular.

vi. replacement theory

Nine years after Yakov and I first met in the executive suite in the back of his theater, he and I are there again, the stage doors flung open to the breeze lilting over the green hills just before Memorial Day, overlooking the section of parking lot where long white stripes of decaying rubber paint mark out the spots for motor coaches, which are about as likely as brontosauruses to ever again fill out these berths, least of all in waterslide season. Back when they did, Yakov parked a red Ferrari here with the vanity plate x red; when I first came by, his ride was a Mercedes SUV with the vanity plate cia; now it is a demure Tesla, and the asphalt in the disused lower tiers of the lot, away to the west, is being reclaimed by boxwood, crown vetch, honeysuckle, mustang grape, and prairie sumac.

Yakov is, for my money, the Branson performer who has navigated and adapted and stagnated in the most interesting ways amid change and stasis, who has been fortunate to ride wave after wave of the past into the future, who has rehashed but also reinvented himself.

One of these reinventions is Dr. Yakov: he earned a master’s degree in psychology from the University of Pennsylvania in 2006 and a Ph.D. from Pepperdine in 2019. The threads of his academic interest are a kind of pop-evolutionary relationship psychology that began to infiltrate his shows and sometimes even took them over—masculine vs. feminine energy; independent vs. co-dependentvs. co-supportive dynamics; how romantic dyads are pairs of magnets (available for purchase in the lobby, $20); the foundational importance of shared humor. He has hosted a PBS special, Happily Ever Laughter: The Neuroscience of Romantic Relationships, and his dissertation, which at points rather casually uses his audience as a test group (n=4.5 million), is titled Law of Laughter (LOL). “As long as they’re laughing at those men/women jokes, they feel safe,” Yakov says. “When I get serious, they get confused—am I a psychologist or am I a comedian?” He tells me that when Branson was shut down for COVID, he spent four months in Bali among many Russians, some of them young enough not to have known Communism. None of them knew who he was. “They were not expecting me to be funny. I was able to do workshops, seminars, conversations with people.” A number of Dr. Yakov’s participants were beautiful, accomplished single women who were serially unlucky in love; afterward, he says, “several of them stated that they changed their lives completely.” In this mode, and resonant with his overall look, he seems more than anything like a benign cult leader.

Side pursuits like these would have been impossible during the motor-coach glut of the Nineties, when Yakov kept up a pace of four hundred shows a year. But then the very old—the parents of the just plain old (I stole this joke from Yakov, by the way, and he can have it back when I am dead)—began to pass away without being replaced: these days, Yakov says, “the older people come as long as they can get in their RV or their SUV—and normally it’s couples that come together—and once they can’t do that anymore, they stop.” We talk about my mother, whom I have just come from visiting in Austin, and whose long-haul driving stamina has dwindled to under an hour. The replacement of bus visitors with car visitors also fed the rise of the time-share industry: now half the tickets Yakov sells in a season might go, at a steep discount, to industry reps who hand them off, cheaply or gratis, often with the promise of free lodging, in exchange for a “two-hour” sales presentation. Folks visiting Branson sometimes skitter away from me when I approach them cold to ask questions, assuming that I am one of the ubiquitous, predatory time-share “body snatchers.” (But no body snatchers, I begin to notice, ever approach me; I mention this to a woman who works for one of the town’s many time-share bailouts, and she instantly responds, “You don’t have a wedding band on and you’re by yourself.”)

As the audiences thinned out and the value of tickets eroded, Yakov halved his engagements in the working months of the year. Then, a decade ago, he resolved to claw his way back onto the national stage.

When I visited one Christmas season, I happened to arrive in town just hours before his first foray in this effort, chancing across a simple printer-paper flier for a free sitcom pilot taping that very night. The show is about one Professor Yakov, who, like Yakov, teaches a “relationships” course at Missouri State and is in a second marriage to which each partner has contributed two adult children. The wife is a restless empty nester, the psych department janitor a well-meaning idiot, and some rich Koreans are peripheral.

Yakov’s timing for the camera may have been rusty, or thrown off by the presence of a regular theater audience, so the good jokes I remembered from elsewhere didn’t land. The new jokes were often of a lower standard (“I’m a marriage counselor, not a magician”), and both tended to get lost amid the woodenness and nonsense of the dialogue. But above all, the package was stylistically of another time, beyond the way most TV sitcoms have been retrograde and aggressively tame in their own eras. Yakov told the audience he was aiming for network prime time, something like Home Improvement or Everybody Loves Raymond, and those comps were historically accurate. He had made a mint reworking his successes of the Eighties, so why not try a revival act with the feel of another decade?

Yakov wound up living back in Malibu half of each year, giving Hollywood another shot, trying to push the sitcom and other projects. But they went pretty much nowhere. And so after six years, he left. His final night in L.A., as he got ready to get out of California lest any kind of serious COVID restrictions trap him there, he went to the Comedy Store, as was his occasional habit, to try out new material, that evening joining Pauly Shore and Joe Rogan. The next day, a comedy producer with a quintet of Grammys called. He’d noticed Yakov on the lineup the prior night and sent an emissary, and was fascinated to learn more about him—being in his early thirties, he’d just known Yakov as the “Russian inversion” guy. The production company sent out a researcher who holed up in Yakov’s archive in Branson for three days binge-watching, and the producer was keen to discuss distributing Yakov’s back catalogue. “So I said, ‘Why do you want me on your roster?’ They said, ‘Because the nostalgia is going through the roof.’ People want that comfort, I guess.”

Yakov has become polyvalent: for an elder millennial–Gen X demographic looking back at the figures of their childhood, he is a cultural comfort, while continuing his long second act as a mascot of ingenuous civil-religious patriotism. (In the way that most political “ideology” is mere cognitive preference, not philosophy, perhaps—partly analogically and partly coextensively—much conservatism and patriotism are mostly nostalgia.)

Nor, it turns out, is Yakov willing to relinquish his claim on the truly old. He is going to bring them back. “I have plans. . . ,” he tells me, unfurling a set of artist’s renderings on the table in front of us: His mountaintop, but the theater is gone. The site is transformed into a cluster of sleek low- and mid-rise buildings, “ . . . to create a retirement community on this land that I have.” The vision is called Yakov Towers. It will be a place, Yakov says, for old people who want to leave the big city, where they feel it is unsafe and expensive, and live out here, in a place they know and love from earlier trips, with three hospitals close by and abundant cheap nursing. The project will include 120 hotel units, 220 of independent living, 120 of assisted living, 42 town-house-style dwellings, and for those who have drunk already of Lethe’s waters, 80 units of memory care. For those who never forget, in the front is an eight-story LED wall of Yakov’s 9/11 mural.

Housing hasn’t generally been a growth sector in Branson—the overbuilding of the Nineties allowed for the repurposing of older motels as extended-stay housing stock for upwards of two thousand people, about a fifth of the population, in accommodations that were never designed for residential use, haven’t seen an out-of-town visitor for years, and have become a byword for precariousness and poverty. The previous resident of Ian’s extended-stay room was a woman who died there; Clay fell out of touch with a friend who used to do merchandise for the Beatles tribute show and whom he, years later, while delivering meals-on-wheels to an extended stay, found much altered (no legs, living in filth). The man died there the next week. But meeting one’s end in Branson need not be a grim accident of the marginal life—now people will be dying to get in!

“The theater at this point is very hard to maintain and have the business flowing through here, so this was kind of like, Okay, so what else can I do? So I’m looking ahead and there might be a small theater in there, but nobody needs a two-thousand-seat theater anymore.” (He’s right: the rear sections here and in the other big venues would, if they could, return to nature like the surplus parking.) It should be enough to have a cozy setting, just for Yakov’s captive audience and the occasional drop-in, ideally paying the walk-up price like in the old days.

We need to wrap things up. “I’m gonna go and get ready. My wife is still in Ukraine,” he says. “She’s coming Tuesday, I need to prepare.” I didn’t know his wife was also Ukrainian.

“Yes. She’s from Kyiv, I’m from Odesa.”

Like Golda Meir and Isaac Babel, I offer.

Yakov smiles. “When the tower is here, your mom’s welcome.”

I realize something as I sit in God and Country watching Jerry Presley sing “In the Ghetto.” Jerry’s proud of his voice—he has Elvis’s constant slight glottalic engagement nailed—but his stage look relies heavily on the Elvis of later years (Aloha from Hawaii, Vegas), because he cannot pull off early Elvis. Jerry, you see, is past seventy. He doesn’t even look like “Old” Elvis. Elvis was in rough shape when he died, but he was forty-two.

Elvis tribute artists often go pro around the age Elvis himself did—Jerry and Dean Z, of Clay Cooper Theater, were both teenagers—and focus on Young Elvis. But they don’t quit Young Elvis, or Elvis at all, at any particular point. As when actors in their twenties play adolescents and tweens play children, this adds an uneasy bloat to reality. Elvis continues to live, into ripe middle age and beyond, and becomes a man he never was. (Branson’s John Denver tribute artist, by the time he made it a dozen years beyond Denver’s, had taken up federal wire fraud.)

Performers who, at some point, made a name for themselves more widely do something similar and present as they were at a distinctive peak moment of their careers. Their projected highlight reels are a premature memoriam, like Andy Williams’s holographic resurrection tour. They become self-impersonators. And as the audiences age with them, together they triangulate an increasingly distant span of the past.3

I realize another thing: only one tribute or original in town is completely free of these glitches, and that is Jesus. The show is one of the newest in a series of lavish biblical productions put on by Sight & Sound Theatres, which has one other location, in Lancaster, Pennsylvania, and whose elaborate sets, menageries, and special effects signal big-time funding that puts them above the local ticket-broker fray. Palestine here has the rolling verdure of a Swiss tourism promo, and Jesus’ dialogue and acting and casting are subtly bizarre and overtly anachronistic: Caiaphas is Alan Rickman’s Sheriff of Nottingham, one of the disciples’ wives is a sassy slap-happy mammy, and Jesus has a glib, cheesy, chipper charm: “Martha, my home away from home!”; “Never really liked your cooking— I love it!” He pats folks on the arm to comfort them and invents the Lord’s Prayer as a conversational outtake.

There is a wisdom in this weird imitation of Christ: Jesus is not trapped in history the way you or I or Yakov or even Elvis (peace be upon Him) are, and for demotic Protestantism, the “personal relationship” should be with Jesus as He could exist in any specific moment, growing with us yet eternally young.

vii. rendezvous

As I departed Branson for the last time, I detoured south and east through the trackless horror of Arkansas: for Steven, whose letter had drawn me here in the first place, had long since gotten free of the town, moving around between cities like Springfield and Fayetteville—where he had been close enough to hop on over when I came to town—and eventually to the part of greater Memphis that lies just over the Mississippi state line.

In the decade and change since he first wrote me, I came to feel bound to Steven for all kinds of small ineffable self-serving reasons, but I think mainly because we found each other back when it was still an unexpected gift to discover that someone you’d become accidentally interested in had put a large archive of thoughts and feelings out there for you to comb through, before the advent of the commonplace, frictionless seduction and squabbling of whatever version of the web we’re on. In the intervening years he co-parented his son while negotiating with his ex, having become divorced from her, about where they would all live (the source of some of his animus toward Branson, he later admitted), realized he wasn’t cut out for personnel oversight (“generally not a leadership type of person”), and consequently switched jobs, from managing a Verizon retail store to the company’s telesales division. He planned a trip to Europe, but the pandemic messed up those plans. His Twitter account was hijacked by Russian spammers, and it took him years to notice. He had anyway killed off his website when he suspected his job prospects were being hurt by his politics, and he felt, in hindsight, that his blogging was a product of having “way too much time” on his hands.

That had manifestly become truer of me than of him, and when I greeted him that warm, muggy afternoon on a macadamized expanse of the mighty river’s alluvial plain, I found he had grown a handsome, tidy beard, and his chestnut hair was long enough to put in a bun, giving him the air of a calendar-art Jesus. I teased him about it gently and then remembered how shy he is.

Starbucks had removed its tables to keep people apart, so we broke with tradition and went to a local chain restaurant next door, for fried snacks and sodas. The gravity of middle age’s onset now bent the arc of our conversation toward tedium—how Memphis proper’s higher cost of living might be offset by Tennessee’s having no state income tax, the delight of mileage reimbursements, the holiday-rental potential of an underutilized vacation property. I was surprised and pleased when he told me he had joined a local writers’ group. When he had stopped publishing in the preceding years, it was as if my original and favorite Branson entertainer had just closed up shop without warning, taking with him the melody of his misguided semicolons. I had assumed he was casting off certain ambitions as he grew older.

“So you were in Branson?” he asked. “What were you doing out there?”

Growing older and casting off certain ambitions myself; having taken up the demeaning hobby of short fiction; and having learned, like Steven, that what far more artists want from art is not income but connection, it had lately occurred to me that I’d have regretted it had I wound up writing at length, parsingly, youthfully, about this quixotic oddball, and (though I miss the self who would have done it) I was glad I had kept delaying the project. Branson became, as you can see, the focus of what you are reading, but Steven will remain its reason for being. So at long last I told him as much, offhandedly enough that (I think) I did not terrify him. I did not go so far as to reveal that on my first trip down I’d intended to see Andy Williams perform “Moon River,” maybe even as a second encore, in order that I might, like one memorable Steven short story, echo the plot of a Simpsons episode, and that Williams’s death four days before I arrived had made me, even before the chickens and the white tigers came into the picture, superstitious about the whole undertaking.

I asked Steven what he made of the town these days. Had age and time softened his perspective, I wondered—could he miss a place he had once found such a provocation?

In the past he’d told me about Branson business he’d heard about or experienced firsthand: school funding, labor conflicts, corruption, hypocrisy, and vice, always fairly concrete. And there was some of that this time, too, but he had also become looser in his impressions. “It’s kinda weird to go back,” he said. “It’s really a strange town.” His parents still lived in the area, he explained, and his son, now thirteen, always liked Branson, so they’d driven up the past winter and stayed in a hotel like tourists, one pair among all the parents and kids. “He misses it. Like, I tell him it’s not really a good place to live. You don’t really have opportunities . . . It’s just such a small town, in the middle of nowhere. When you drive there, you’re just in the woods—then you’re in this hillbilly town, but it feels like a beach town.”

We covered other ground but he came back to this. “It’s really designed to be a cliché, the whole town is. It’s kinda cool, I guess. In a way.” Then, staring past me, as if he were speaking aloud a thought he’d been turning over silently, “Like I said, it’s kinda like a beach town.”

The description wouldn’t ever have occurred to me, since Branson is so deeply landlocked—notwithstanding the baptismally seductive lakes and rivers that lie amid its hills. But as I tried to picture it, I reckoned he might be right: The colorful plastic landscapes of all the sundry pleasure gardens of mini-golf and water-park frolic and go-karting, the slow traffic winding past all that boardwalk abundance under the holidaymaker’s brainless blue sky. Mostly New Branson. Neither of us was quite old enough to know Old, though I still feel the loss of its passing.

I took my leave of Steven until another however many years, or never again, whichever comes first, now in a hurry to make it to Nashville in good time, and so gave up the chance to detour off I-55 and see, lying less than a mile distant, the gates of Graceland.

viii. night at the museum

The previous evening, I have a plan to meet the men of Motown Downtown—the only long-running African-American act in Branson—over on West 76 Country Boulevard and do a kind of casual photo shoot, maybe sequined shoes bathed in the red light of crawling LED signs, but the hour draws late, and having heard nothing I call their linchpin, Rico J, to check in, and he tells me sorry, the guys are all napping before the evening’s song and dance. I suppose a Motown nap is like a disco nap, except you’re old and don’t do drugs later. I decide all the same that I will go have a solitary bask in the warmth of the strip, and being in the relevant sub-sub-sub-microdemographics of my elder millennial–Gen X edge cohort, I do so on gray-market psychedelics, not such a quantity that the neons and screens will overwhelm me, but enough to open my heart in a curious way to whoever might cross my path, whether weekend rambler or angel incognito.

With night freshly fallen, I meet Amber and Johnny, newlyweds up from Tulsa, who are just emerging from the Wax Museum and say they were the only visitors in there, black or white, among all the paraffinous undead. (My guess, by the way and for what it’s worth, is that Clay’s friend was right: Michael Jackson might be a draw, not because he’s Black Jesus or anything but because he’s the one figure for whom this uncanny yet unpersuasive form of imitation seems actually fitting, the self-sculpting paragon captured, not realistically but faithfully, amid the flux of relentless change.) I ask if they’d like me to take a few honeymoon photos, since I’ve got my camera in my car from the cancellation. They accept.

I suspect that for at least one of them it’s not a first marriage, though with my Big City eyes it can be hard to tell how old people in Real America are. Sometimes when I am in a strange town I swipe through Tinder with a blank profile, to get a cross-section of how locals look and dress, how modestly clothed or heavily made-up or digitally filtered they choose to be, and down here (where it’s all locals—nobody comes to Branson to be on the apps) I’ve noticed hard lives of a certain kind adding an extra five or ten years. At any rate, for whatever reason, I sense experience in this couple and hope to elicit some oracular wisdom, so I ask what they would pass along that they hope others might receive. Who am I to keep pontificating and wittering on, one man fetched up in the lonely hills of southern Missouri in the night? “These hills belong to me,” the old Shepherd says to an outsider in Wright’s novel, “only as they belong to all who have the grace to love them. . . . Your brothers need the truths that you will read here; unless the world has greatly changed.”

It could be, I prompt them, about marriage, or this town, or this country?

Amber speaks first.

“You have to embrace the flaws.”