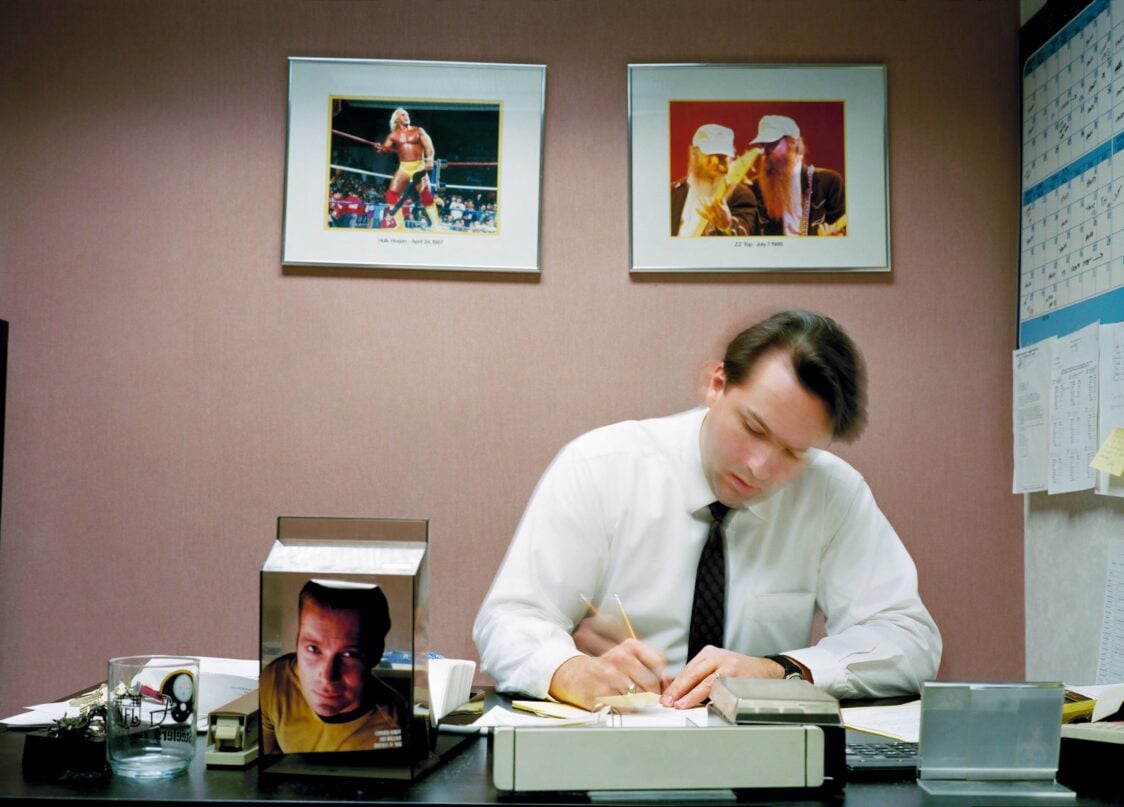

A photograph by Steven Ahlgren from his book The Office, which was published by Hoxton Mini Press © The artist

I’ve never visited the office of this magazine. Oh, sure, the editors have invited me up—they’re very polite—but I’ve declined, because an unseen office is a useful thing. The imagination can tailor it to any occasion. Say I’m stuck mid-paragraph and need to summon some intellectual sangfroid. I picture the magazine’s brightest and best in saddle-leather armchairs, snifters of Armagnac aglint in the sunset, sharpened red pencils fanned out in an empty jar of genuine Dijon mustard. But my words will be judged too sternly in a place like this. I make it more approachable, fusty, with fiberboard ceiling tiles and eye-scalding LED bulbs. It wears its history lightly. Encased in dust on a high shelf is a signed first edition of a Pol Pot biography that sold three hundred copies. In a disused drawer survives a malcontent note from one intern to another, scribbled on a receipt from a sandwich shop that closed in 2009. Now my column is late. I have to convince myself that no one cares. The office becomes unbuttoned, juvenile. There’s an air-hockey table, two liters of Sprite going flat in the fridge. Someone high on the masthead sips Lipton from a faded Garfield mug. Everything will be okay.

I haven’t worked at an office in years. I miss them, especially magazine offices—not in the Zoomed-out way that we’re supposed to miss them now, but as catalysts for social and antisocial behavior alike. I miss the gossip, the stilted gatherings, the unexpected displays of hierarchy, the way our shared purpose was always coming in and out of focus. The scent of microwaved leftovers wafting over cubicles. The being there was actually really nice; it was the having to be there that sucked. As the hours accrued, I learned my colleagues’ footfalls so well that I could tell when they needed urgently to move their bowels or when they’d taken an Adderall. Wilfrid Sheed published his novel Office Politics (McNally Editions, $18) in 1966, thirty years before the FDA approved Adderall, but he’d have known what I mean, which is one of many reasons it makes sense to reissue this book. One of his characters, the illustrious Gilbert Twining, keeps “pep pills” in his desk. Twining edits a small literary magazine, so he can’t be caught unawares; like all editors in chief, he presides over a subtle, daily psychodrama that consumes his entire staff. This is what Office Politics is about: the ironies of jockeying for influence at an uninfluential periodical. As one editor says, “I mean it’s a good little magazine—but really. On a cosmic scale—”

The cosmos means nothing to Twining unless there are potential subscribers out there. He’s helmed The Outsider for seven years, and its circulation has slipped from 27,000 to 21,000. Is it stale? Or is staleness actually a mark of quiet distinction, as for magazines it often can be? Whatever the case, The Outsider has become the sort of publication with “a reputation that shrank a little every time a subscriber died.” Twining maintains that it’s “possibly the most civilized magazine in the United States,” but somewhere between the long, scheming lunches and longer, martini-soaked evenings, he has to settle in and read the thing. Its contents are the “most soporific stuff in the world”: pieces on farm surpluses, action painting, federal funding for education, Nyasaland. In a word, literature.

Twining considers himself the magazine’s “constitutional monarch.” Then the king suffers a heart attack. His three senior editors vie clumsily for the throne, distracting and neutralizing one another as only men of letters can. (“Brian or someone had placed on his desk a dingy-looking article about the gold standard.”) George Wren, the most starry-eyed and newest member of the bunch, has long adored The Outsider, but up close he finds it a far grubbier affair, especially without its charismatic leader to tramp around “wearing squalor like a badge.” The office—a “greasy little play pit,” per one colleague—is too cramped to afford private conversation. What it lacks in natural light and fresh paint it recoups in pettiness and resentment. The magazine is so understated, so distantly bemused, that its philosophy hovers between elusive and nonexistent, “adding up to urbanity, lack of fluster, loyal, courteous, brushes teeth after every meal.” But Wren can never quite bring himself to quit, even when he feels that putting out a new issue is

like wheeling an old gentleman down to the promenade for his afternoon airing. No one expected anything fresh and exciting. . . . Did this happen to all magazines? He supposed it must. The editors clamored for new ideas, but always found something wrong with them, and were drawn magnetically to the old ones; and old subscribers woke up just long enough to deplore any change in layout, any modification of the puzzle page.

Well, imagine reading that as you sit down to write a column whose format hasn’t changed in more than twenty years. Flip ahead to the Puzzle (page 79), and you’ll see that it, too, is intact. I wish I didn’t recognize myself, and most of my peers, in Wren as he vacillates between cultish literary devotion and despair; I wish I didn’t see certain bosses in Twining, who grooms successors only to devastate them with offhand pronouncements about their work. (“These won’t do, you know.”) The jokes in Office Politics are still funny, and its weariness still resounds, one subordinate’s sigh at a time, within the 501(c)(3) nonprofit organizations that today produce our most important, least-read magazines. Sheed’s novel has warmth, too, and plenty of wisdom about finding meaning in life and how to face middle age among moribund institutions. Also the risks of becoming an institution oneself: an editor thinks that one of his star writers “had actually been quite a good critic in his day, with enough native intensity to last about two years—after which most critics should be shot anyway.” This is the book I’ll remember as I’m led to the firing squad.

Untitled, by Gabrielle Garland © The artist. Courtesy the artist; Corbett vs. Dempsey, Chicago; and the Pit, Los Angeles.

The Outsider’s office manager believes new furniture could turn the whole magazine around. There’s no room in the budget for such extravagances, but reading Harald Jähner’s Vertigo: The Rise and Fall of Weimar Germany (Basic Books, $35), with its many manifestos and rhapsodies to the New Man, the New Woman, the New Building, it occurs to me that she was correct. The right seat will change the sitter. The Bauhaus’s famous Freischwinger chair debuted in the late Twenties with a cantilevered, tubular steel design that made one feel “ready at any moment to catapult oneself back into active life,” Jähner writes. “It matched the intensely nervous mood of the era.”

Jähner, a German journalist, enjoys studying his nation at its most defeated, in the liminal periods when its identity was demolished and tentatively rebuilt. He eschews provocative theories and sweeping reevaluations, instead sifting through song lyrics, novel excerpts, newspaper clippings, and paintings in search of fugitive cultural history. His last book, Aftermath, about picking up the pieces after the fall of the Third Reich, wrought emotion from stones (Jähner writes with surprising poignance about rubble clearance). In Vertigo, he finds the passions of Germany’s first democratic republic ignited by traffic, typing pools, herbal diets, and the Charleston; after the turbulence of the First World War, there was “a desire to consume, a desire to dance, a hunger for experience, pride and hatred.”

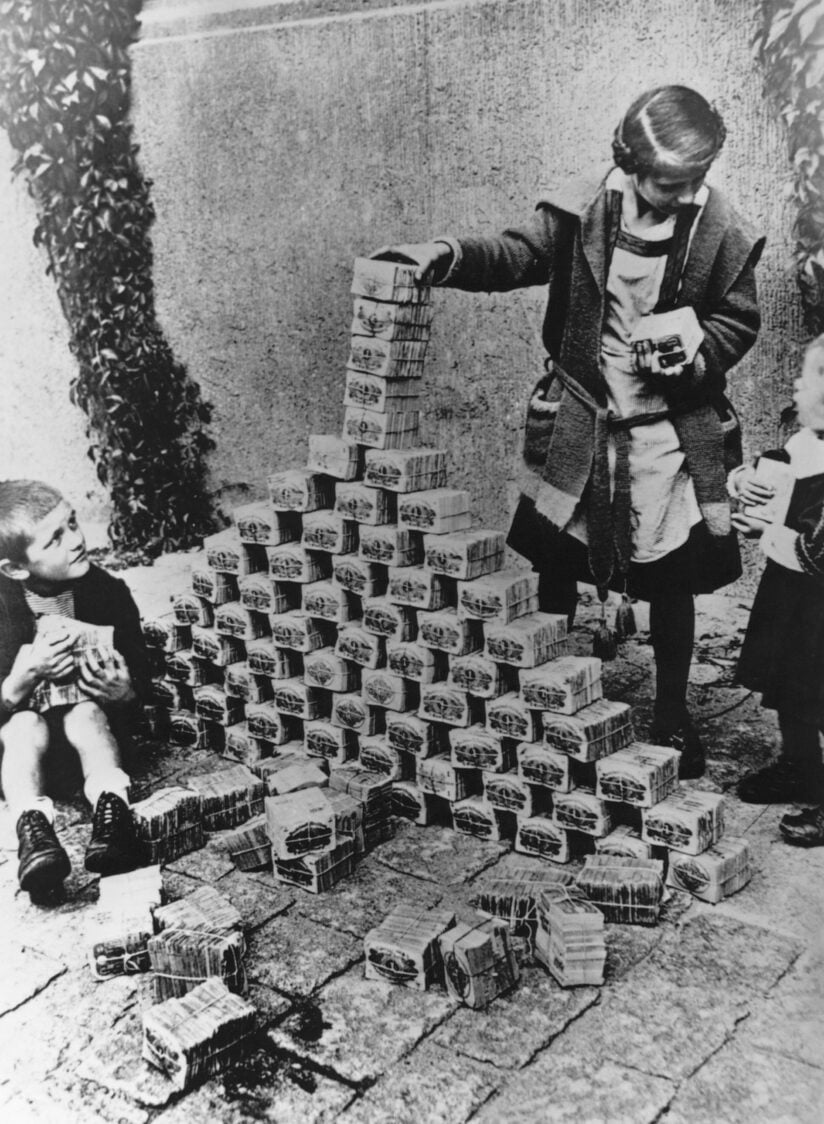

The new Germany couldn’t tell its birth pangs from its death rattles. Everyone and everything was too fragile to be trusted. As nightclubs surged with manic energy, a revue composer warned Berliners to a jaunty tune: “You can’t dance the shame from your body. . . . In the middle of your foxtrot there’ll be a bang and then it’s night.” Hyperinflation so devalued the mark that some theatergoers paid for their tickets with eggs. Parents gave their children bundles of banknotes as playthings.

German children playing with money in the street, 1923 © Hulton Deutsch Collection/CORBIS/Getty Images

Some felt that the nation’s morals were devalued, too, as the visionary and the voluptuary went hand in hand. Dance teachers campaigned against “the misuse of dancing freedom.” “Why should we be more stable than our currency?” wrote Klaus Mann, Thomas’s son. “Millions of underfed, corrupt, desperately lewd, furiously pleasure-seeking men and women twist and stumble away in a jazzy delirium.” Of course, even people in the jazziest of deliriums had to work, and for this they went to offices, which were larger and more official than ever. No one had ever seen so many desks under one roof. Commentators noted the rise of the “Salaried Masses” practicing “the bent or seated way of life.” There were armies of secretaries now working in high-rise “palace[s] of administration,” living in hulking, functionalist structures, their kitchens sometimes no larger than cockpits. They danced alone, or with gigolos (Billy Wilder was one), and dressed as if they believed themselves pharaohs. Most offensively to the old order, women sometimes wore monocles, which, as Joseph Roth noted, were the defining accessory of a kind of constipated, upper-class German man. “The monocle only stayed in place if the man held it there with his facial muscles,” Jähner explains:

It acted as an emotional brake. . . . A reminder to avoid spontaneous reactions; sudden laughter, for example, would unfailingly make the glass fall to the floor. The wearer was condemned to a stiff body posture, and became accustomed to reacting as slowly as possible to spontaneous things and events. “That is the reason why his face is so empty and so nobly discreet,” Roth observed.

If women could boast such severity and emptiness, what were men? The old categories were blurring together. New traffic signals included a yellow light between red and green—these patterns seemed to dictate how citizens should think. As Siegfried Kracauer wrote, very Germanly: “By introducing an intermediate light, caution is to a certain extent objectivized and initiative displaced from people.” On the rooftops, meanwhile, critics read between the lines and the angles, too. The flat roof—which, according to its proponents, “meant that conscience had finally awakened”—was a freighted alternative to Germany’s traditional gables, though some reactionary architects, such as those of the Heimatschutzstil (“homeland protection style”), maintained that flatness was irredeemably African, Arab, Communist, or Jewish.

Jähner has an attuned sense of the Weimar mood—an amusement-park ride whose heady, dizzying thrills soon gave way to a long bout of national nausea. The Reichstag fire burns in the distance, and precursors to Nazism are everywhere in evidence; the coming violence feels ineluctable. Even the popularity of hiking, Jähner muses, “with its aspiration to harmony with nature, made way for the aggressive conquest of space associated with marching.”

It takes no effort to see such harbingers of doom in our own time, but the Weimar strain of exuberance, of delight and desperation in reinvention, is harder to find. “The old world is in decay, its joints are creaking. I want to help to smash it,” said the dancer Valeska Gert in the early days of the republic. “I believe in the new life. I want to help to build it.” Sadly, this reminded me only of Mark Zuckerberg’s former motto: “Move fast and break things.”

Pamela Harriman was a creature of the old world—she grew up in the secluded Dorset countryside of 1920, the daughter of the eleventh Baron Digby, with a family crest that featured “an ostrich supported by two monkeys with a horseshoe in its beak”—who helped build the new one by perfecting the love affair as a form of statecraft. By the end of her life, she’d become the U.S. ambassador to Jacques Chirac’s France, but if people remember her today, it’s as “a conniving and ridiculous gold-digger obsessed by sex,” writes her biographer, Sonia Purnell. With Kingmaker: Pamela Harriman’s Astonishing Life of Power, Seduction, and Intrigue (Viking, $35), Purnell convincingly turns a comic-book enchantress into a sensualist operator, equally fluent in U.N. Security Council resolutions, table linens, and oral sex.

The Digby mansion had fifty rooms and not, it seems, a water closet among them; Pamela’s grandfather thought bathrooms were “disgusting.” If such refinement was in the blood, so was scandal. One of her ancestors had divorced her husband and eventually ended up in Paris, where some say she slept with Balzac. Pamela saw that, with her aristocratic bearing and flawless complexion (“absolutely strawberries and cream,” one admirer called it), she, too, could use sex to expand her horizons. At nineteen, she married Winston Churchill’s rough-hewn son, Randolph, who’d proposed on their first date (apparently, she was the ninth woman he’d asked that week). Boorish, drunk, and frequently in debt, he made a regrettable husband until his father became prime minister, sweeping Pamela into the corridors of power. She helped the war effort by seducing W. Averell Harriman, a handsome American dispatched to London to run the Lend-Lease program. Their affair began after they watched a bombed Selfridges department store burn down. “There was nothing like a Blitz to get something going,” Harriman later said. Soon he was sharing pivotal information about the American war effort, or lack thereof, with his paramour, who promptly relayed it to the elder Churchill. Purnell refers to this as “Pamela’s strategic sex life”—a kind of lusting gamesmanship sustained seemingly all of her affairs, which, in turn, sustain this biography of more than five hundred pages—arguing that she “helped to weave” the nations’ special relationship, which “began between the sheets of the Dorchester Hotel.” Instead of closing her eyes and thinking of England, she kept them open and thought of America, too.

Purple Tulips, by Romina Milano © The artist. Courtesy Paradiso Images, Barcelona

Her relationship with Harriman enabled her ascent in Washington, but their official union came more than a quarter century later, after his wife had died. In the interim, Pamela bedded, among others, a Rothschild; a Niarchos; Gianni Agnelli, heir to the Fiat fortune; Edward R. Murrow, who smoked not just after sex but during it, letting the ash fall on his pillow; Prince Aly Khan, a dynamo who’d spent six weeks learning to control his orgasm under the tutelage of a doctor in Cairo; and Leland Hayward, her second husband, a thrice-divorced Broadway producer who ate only white foods. When Pamela died, in 1997, following an afternoon swim at the Hôtel Ritz, obituaries called her a home-wrecker. But these weren’t homes. They were dynasties, ventures—corporations that happened to be families. Pamela’s romances gave her access to their ironed curtains, Hermès scarves, white-gloved butlers, and a flower bed “planted with 2,500 pastel-colored tulips personally selected by Billy Baldwin.” (The decorator, not, alas, Alec’s brother.) Purnell marshals a lot of sympathy for Pamela, but in the end hers is a story of old money, amorality, and soft power. One of her fans was Bill Clinton, who speaks on the final page: “Did she have a good time living? Yes, she did. Good for her.”