Collages by Catie O’Leary for Harper’s Magazine

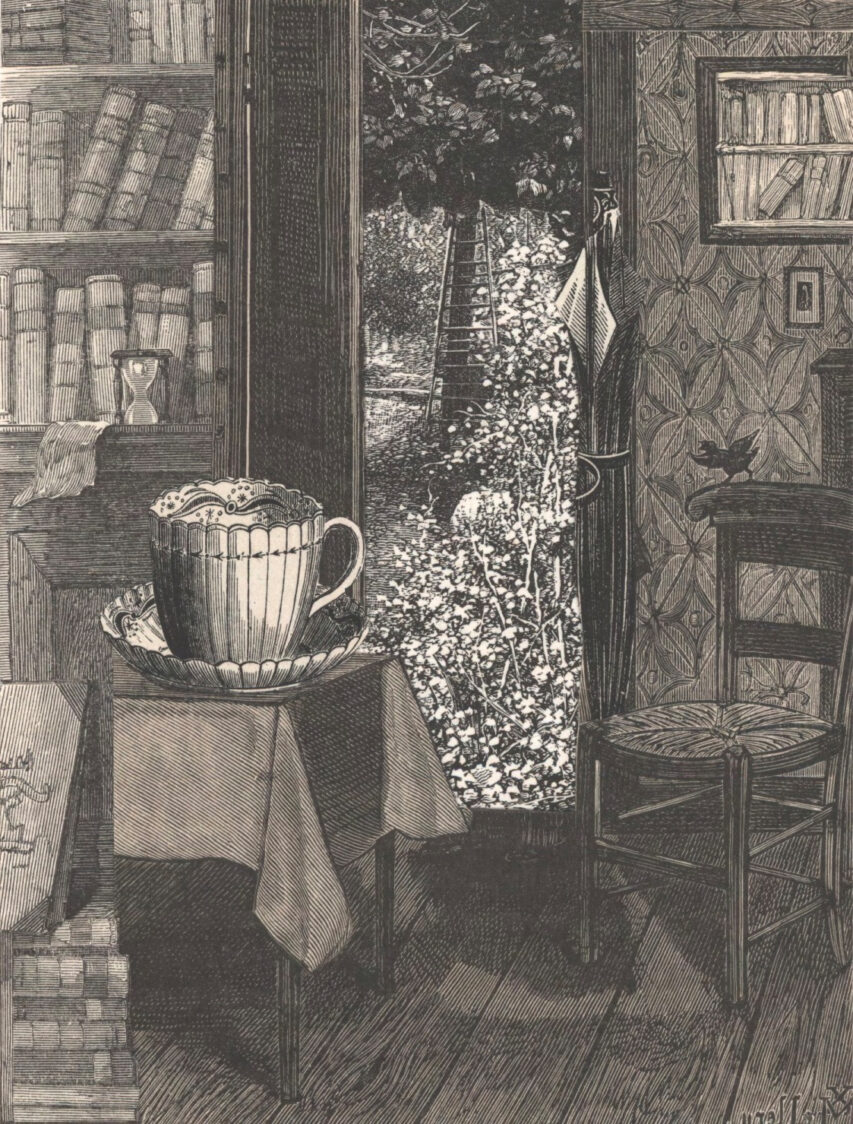

There is someone in the house. Heard as he moves around the room upstairs. When he gets out of bed or when he goes down the stairs and into the kitchen. There’s the gush of water through the pipes when he fills a kettle. The sound of metal on metal when he sets the kettle on the stove and the very faint click when he turns on the gas. Then there’s a pause until the water comes to a boil. There’s the rustle of tea leaves and paper as first one, then another spoonful of tea leaves is taken from a paper bag and poured into the teapot, then the sound of water being poured over the tea leaves, but such sounds can be heard only in the kitchen. I can hear the fridge being opened, because the door bumps against a corner of the countertop. Then there’s another pause, while the tea steeps, and in a moment I’ll hear the chink of a cup and saucer being taken from the cupboard. I don’t hear the sound of the tea being poured into the cup, but I can hear footsteps moving from the kitchen to the living room as he carries the cup of tea through the house. His name is Thomas Selter. The house is a two-story stone cottage on the outskirts of the town of Clairon-sous-Bois in northern France. No one enters the back room overlooking the garden and the woodpile.

It is the eighteenth of November. I have got used to that thought. I have got used to the sounds, to the gray morning light and to the rain that will soon start to fall in the garden. I have got used to footsteps on the floor and doors being opened and closed. I can hear Thomas going from the living room to the kitchen and putting the cup down on the countertop and before long I hear him in the hall. I hear him take his coat from its peg and I hear him drop his umbrella on the floor and pick it up.

Once Thomas has gone out into the November rain, there is silence in the house. Broken only by my own sounds and the soft patter of rain outside. There is the scratch of pencil on paper and the scrape of the chair on the floor when I push it back and get up from the table. There are the sounds of my footsteps as I cross the room and the very slight creak of the door handle when I open the door into the hall.

While Thomas is out, I usually wander around the house. I go to the toilet, get water from the kitchen, but I soon go back to the room. I close the door and sit down on the bed or the chair in the corner, so I won’t be seen from the garden path should anyone look in.

When Thomas returns carrying two thin plastic bags, the sounds start up again. The key in the door and shoes being wiped on the mat. The crinkle of the plastic bags when he sets down his shopping. The sound of the rolled umbrella, which he lays on the chair in the hall, and a moment later that of his coat being hung on the rack by the door. I hear the repeated crinkle of plastic as he places his shopping bags on the countertop and puts things away. He puts cheese in the fridge, pops two cans of tomatoes into a cupboard, and leaves a bar of chocolate on the countertop. When the bags are empty, he balls them up and stows them in the cupboard under the sink. Then he closes the door and leaves them to carry on crinkling in there.

During the day I hear him in the office upstairs. I hear a swivel chair rolling across the floor and the printer churning out labels and letters. I hear footsteps on the stairs and the gentle thud on the floorboards as Thomas sets down packages and letters in the hall. I hear him in the kitchen and the living room. I hear the sound of a hand or a sleeve brushing the wall as he goes back upstairs, I hear him in the bathroom and I hear a sound from the toilet that can only be made by a man peeing standing upright.

Presently I hear him on the stairs and in the hall again, then he goes into the living room and sits down in an armchair by the window facing the road. And there he waits, reading and watching the November rain.

He is waiting for me. My name is Tara Selter. I am sitting in the back room overlooking the garden and the woodpile. It is the eighteenth of November. Every night, when I lie down to sleep in the bed in the guest room, it is the eighteenth of November and every morning, when I wake up, it is the eighteenth of November. I no longer expect to wake up to the nineteenth of November and I no longer remember the seventeenth of November as if it were yesterday.

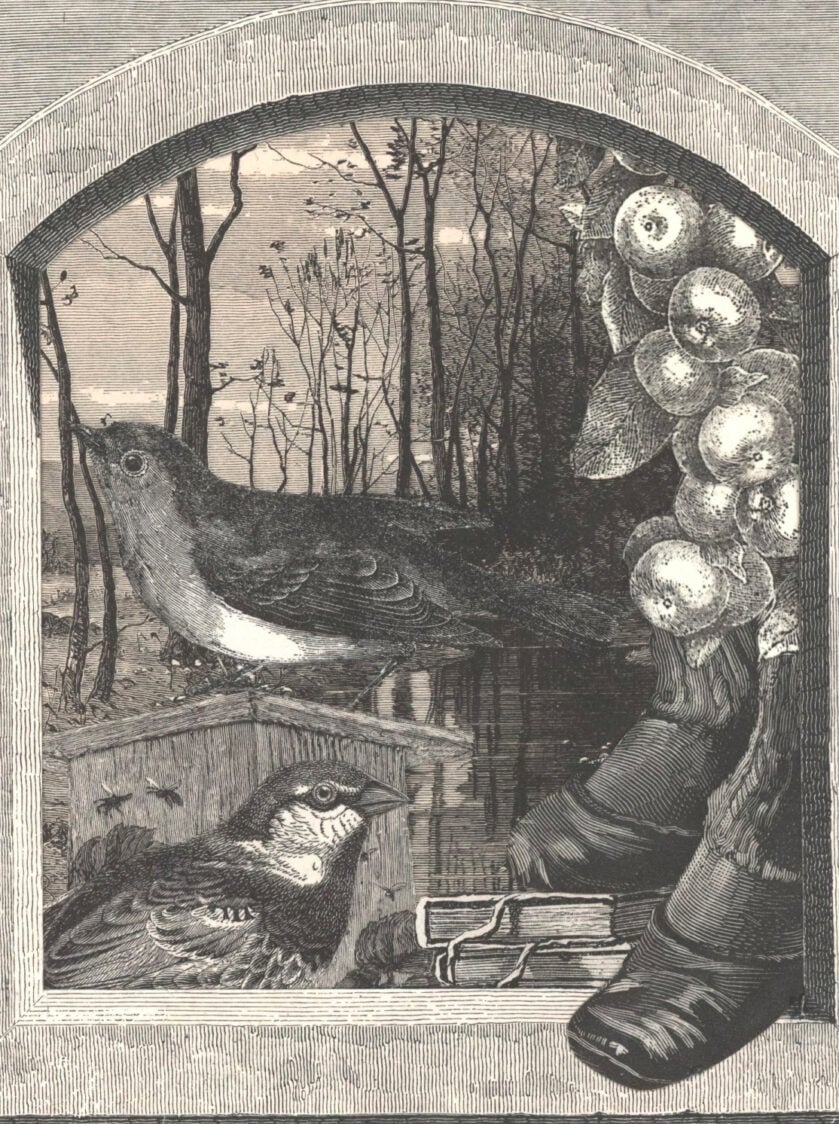

I open the window and throw out some bread for the birds that will soon be gathering in the garden. They show up when there is a break in the rain. First the blackbirds, who peck at the last apples on the apple tree or the bread I’ve thrown out, and then a lone robin. Moments later a long-tailed tit flies down, closely followed by some great tits who are promptly seen off by the blackbirds. Shortly afterward the rain comes on again. The blackbirds carry on feeding for a little while longer, but when the rain gets heavier they fly off to take shelter in the hedge.

Thomas has lit a fire in the living room. He has brought in wood from the garden shed, and I soon start to feel the house growing warmer. I heard the sounds from the hall and the living room, but now that Thomas is sitting with his reading, all I can hear is my pencil on the paper, a whisper soon eclipsed by the sound of the rain.

I have counted the days and, if my calculations are correct, today is November 18, No. 121. I keep track of the days. I keep track of the sounds in the house. When it is quiet I do nothing. I lie down and rest on the bed or I read a book, but I make no sound. Or hardly any. I breathe. I get up and tiptoe about the room. The sounds carry me around. I sit on the bed or gently pull the chair out from the table by the window.

In the middle of the afternoon, Thomas puts on some music in the living room. First I hear him in the hall and the kitchen. I hear him putting a kettle on the stove, hear his footsteps on the floor as he goes back through to the living room and puts on the music. Then I know it will soon clear up. The clouds will pass and there will be a glimmer of sunshine.

I usually get ready to go out as soon as the music starts. I get up and put on my coat and my boots. I stand by the door for a few moments until the music is so loud that I can leave the house without being heard, the strains issuing from the living room masking the sound of doors being opened, of footsteps on the floor and doors being closed.

I leave the house by the garden door. I slip my bag over my shoulder, softly open the guest-room door, step into the hall and close it behind me. On the floor are three medium-size envelopes and four brown cardboard packages with our name on them: T. & T. Selter. That’s us. We deal in antiquarian books, specializing in illustrated works from the eighteenth century. We buy the books at auction, from private collectors or other booksellers and then sell them on, sending them off in brown packages bearing our name. I slip silently past the packages on the floor, open the door, and step outside. I don’t need an umbrella. It is still raining slightly, but it won’t be long before it stops completely. I don’t take the garden path leading up to the gate, instead I turn left and go around the side of the house, past the shed and down to a corner of the garden that can’t be seen from the house. I pass a plot of leeks and two rows of Swiss chard and come to a gap in the fence, which brings me out onto the road. I glance back briefly. I see a thin trail of smoke coiling up from the chimney, hear the very faint sound of music, but I hurry on. A few steps further and I can hear neither music nor rain because the rain has stopped, the music has been left behind me, and the only sounds are my footsteps on the sidewalk, the rumble of a few cars and the distant voices of children at a school some blocks away.

Not long afterward, when Thomas sees that the rain has stopped, he turns off the music. He puts on his coat and picks up the pile of letters and packages from the hall floor. He leaves the house at 3:24. Carrying letters and packages. T. & T. Selter. That’s us. But time has come between us. We walk along the narrow roads into town or back to the house. We are outside, we walk around in a break in the rain, but we do not take the same roads. He does not expect to meet me along the way, nor will he. I know another route, and by the time he returns to the house I am back in the room looking out on the garden.

If there is anything I need, I buy it in a small supermarket a few blocks away. I allow plenty of time and usually take a roundabout way home. I come through the gate and up the garden path to the back door and let myself in. The house is quiet. Thomas is out and it is no longer raining. He is on his way into town and by the time he has dropped off his packages the sun will have broken through. He will take a walk through the woods and down to the river and won’t return until late in the afternoon, after the rain has started again, because there is no one waiting for him in the house and there is nothing he has to do.

Usually, when I return, I leave my shopping bags in the guest room. I hang my coat over the back of the chair, I take off my boots and go through to the kitchen. There’s a cup next to the sink and the kettle on the stove is still slightly warm. I can follow Thomas’s tracks through the house. I go upstairs and into the office. There are piles of books on the desk and a scattering of papers. There are books on the shelves and in boxes on the floor. One of the boxes is open because Thomas has been searching through it for something and hasn’t closed it again. In the bedroom next door to the office, it looks as if someone has just got up, but only one side of the bed has been slept on.

I have an hour and a half in the house before Thomas gets back. I have time to have a bath or wash some clothes in the sink, I have time to take a book from the shelf and sit down with it in one of the armchairs by the window.

If I spend the time in the living room, I usually listen to music or read until it starts to get dark, but today I am staying in here, in the room overlooking the garden and the woodpile. I heard Thomas take his coat off the peg and I heard him leave the house. I opened the door into the hall, the packages are gone from the floor, and now I am sitting at the table by the window. It is the eighteenth of November. I am becoming used to that thought.

On the morning of the seventeenth of November, I said goodbye to Thomas at the door of the house. The time was a quarter to eight, the taxi was waiting outside, and I caught the 8:17 train from Clairon-sous-Bois. I was going to Bordeaux for the annual auction of illustrated works from the eighteenth century. The sky was gray, there was moisture in the air, but it didn’t come to rain.

From Clairon station I traveled to Lille-Flandres, switched to Lille-Europe, and went from there to Paris, where I changed trains for Bordeaux. I got to the station in Bordeaux just before two o’clock and after a moment’s confusion due to road work outside the station, with lots of barriers, signs, and closed walkways, I found my way to the exhibition center where the auction was to be held, arriving there a few minutes later. I registered and was given a program and a badge, which read 7ème salon lumières, followed by my name and, below that, our company name, T. & T. Selter.

I was in good time for the main auction of illustrated books, which was due to start at three o’clock. A couple of auctions had already been held, and I could see from the program that again this year there would be talks and panel discussions, but none that I was planning to attend.

Once inside, I faltered for a moment, slightly disoriented by a scene that spoke of a conference in progress, all closed doors and abandoned coffee cups, until I spotted the signs and arrows pointing to the auction room and the adjoining exhibition hall, where scores of antiquarian booksellers had, as always, set up their stands displaying books and scientific illustrations. I had a fairly good idea of which books I wanted to bid for in the auction, and once I had taken a look at the most important of these, I did a round of the exhibition hall. I said hello to some booksellers I knew from before, and then, at a few minutes to three, I took my seat in the auction hall, which soon began to fill with people streaming out of the conference rooms.

I managed to buy twelve works at the auction. Five for which we had already had requests and seven others for which I thought we could get decent prices. We deal mainly in moderately priced books and sell to a mixed bunch of collectors, most of them in Europe, although we do have a few customers in other parts of the world. As a rule, I am the one who travels to auctions and visits antiquarian bookshops while Thomas takes care of cataloguing and shipping. To begin with we did everything together, but we have gradually split the responsibilities between us. I’m not sure why it fell to me to do the traveling. Maybe because I don’t mind traveling so much and maybe because I very quickly developed a certain instinct for the books, a feel for the paper, an eye for the quality of the printing, for a well-crafted binding. I don’t know what it is, but it’s almost physical, like an inchworm testing whether a leaf is worth creeping across, or a bird listening to insects moving in the bark of a tree. It might be a detail: the sound when you flick through the pages, the feel of the lettering, the depth of the imprint, the saturation of the colors in an illustration, the precision of the details in a plate, the hues of the edges, I don’t know what it is that seals it for me, because even though I generally know which works I’m interested in, usually I’m not absolutely sure whether I want to buy a book until I have it in my hand.

After the auction, I went back to the exhibition hall, paid for some books I had had put aside, and found another six works that I had been looking for, as well as a few I hadn’t known about. I usually arrange for the heaviest and most valuable books to be sent straight to Clairon-sous-Bois, but I often take a few of my purchases away with me in my bag: on this occasion, a pocket encyclopedia of birdcalls arranged by note, new to me; a second edition of Harcard’s book on the anatomy of animals; and a fine copy of Boisot’s renowned book on spiders, Atlas des Araignées, which one of our regular customers wished to give as a present to a friend and which we had therefore promised to look out for.

Late in the afternoon on the seventeenth of November, I boarded the train to Paris and arrived late that evening at the Hôtel du Lison, where we usually stay when we’re in town. The Hôtel du Lison sits on the corner of the Rue Almageste, where several of the antiquarian booksellers with whom we deal have their shops and where our good friend Philip Maurel has his antique coin shop. My plan for the next two days, apart from buying books for our business and seeing Philip, was to visit the research library Bibliothèque 18, in Clichy, where I had an appointment the following day, the nineteenth of November, with a librarian by the name of Nami Charet, who had written an article on some hitherto overlooked variations on eighteenth-century printing techniques. Her discovery of certain changes to engravers’ tools and working methods had made it possible to date illustrations from the end of that period with great accuracy, thereby shedding light on discrepancies between their genesis and year of publication.

Once at the hotel, I called Thomas. It wasn’t a long conversation. I told him about the day’s finds and asked him if he had any titles to add to my list for the next day. He had come up with a couple of works that he thought would be worth looking for, and he had also just arranged with two of our fellow dealers in the Rue Renart, a side street off the Rue Almageste, to have a couple of books set aside. He asked me to examine them and to buy them if they were in decent condition. I added these titles to my list and promised to go take a look at them. I think we chatted a little more about the auction and a bit about the November weather before we said our good nights and hung up.

We try to avoid long phone calls when we’re apart. Not only because otherwise we would just end up having long, detailed dialogues on the condition of the books, publication years, the illustrations, and the pricing, but also because such conversations seem to increase the distance between us. The minute we deviate from simple, practical matters, the conversation lapses imperceptibly into a kind of audio link, a muted love mumble. Our communication, initially meaningful and coherent, turns into a series of fitful exchanges containing neither sentences nor information: little words and sounds meant—I suppose—to keep the line between us open, but that, instead, make all too clear how far apart we are. So we have learned to split the work between us, stick to practical matters, and speak to each other only when necessary.

I’ve forgotten many of the details of our conversation, but Thomas—who remembers the seventeenth of November as if it were yesterday—has told me that I had spoken in glowing terms of my day’s haul and that I had been wondering whether T. & T. Selter should expand its operations to include scientific plates and illustrations. We talked mostly about the practical problems associated with my suggestion, particularly regarding shipping, which would probably be Thomas’s job. I felt the idea was worth considering, but Thomas was not so sure.

I don’t recall the rest of the conversation, but I do remember that shortly afterward I had a bath and then I settled myself on the bed in my hotel room and ran an eye over my book list. I also remember that I was quite tired from all the traveling, that I set the alarm on my phone, got undressed, and climbed into bed.

I still don’t know whether it would be a good idea for T. & T. Selter to expand into plates and illustrations, but I do know that such considerations no longer have any meaning. I know too that Thomas left his packages at the post office a while ago, that he has been down by the river and past the old water mill, and that he has walked through the woods and will soon be back.

I keep an eye on the rain clouds. The clouds tell me when time is up. The light fades, and I see the sky change to dark gray. If I’m sitting in the living room with a book, it grows too dark for me to read and I prepare to retreat to the guest room. I sit for a moment listening to the rain and, when it intensifies, I know that Thomas will soon be back. I get up from the armchair by the window. I go to the kitchen, rinse my cup in the sink, put it in the cupboard, and come into the guest room. I usually remember to turn the heat up before I leave the living room. The embers in the grate have long gone cold, and when Thomas gets back he’ll be drenched.

But I am not sitting in the living room today. I am sitting at the table in the guest room and the rain clouds are gathering once more. I gaze out at the garden and the apple tree. A couple of apples have fallen onto the grass, a light breeze has blown the autumn leaves almost dry while I’ve been sitting here, but the tree will soon be wet with rain again. I can still see the birds when they dart about in the faint light. They can tell that rain is on the way, but they haven’t yet gone to roost in the hedge.

Darkness falls as I wait for Thomas to go by outside. The writing on the page in front of me becomes hard to read. I’ve shut the door to the hall and moved away from the window. I usually sit on the bed while I wait for Thomas to get back, and I know that first one and then another dark shadow will come along the road at the bottom of the garden. The first shadow is our neighbor. The second is Thomas making his way through the rain. This is the only time I see him: a wet silhouette down by the fence. The rest of the day he is just sounds in the rooms of the house.

Not until Thomas has once again become sounds in the rooms of the house do I turn on a light. I heard his footsteps on the garden path, his key in the lock, and the door being opened and closed. I heard him wipe his feet on the mat and the faint click of the switch when he turned on the hall light. I can see light filtering in under the door, and I have turned on the lamp on the table. My light fills this room and filters out under the door, but it cannot be seen from the hall, mingling as it does to invisibility with the light out there.

I have moved back to the table by the window, and before long I hear Thomas’s feet on the stairs and in the passage again. I hear him in the kitchen and the hall. I hear him open the door facing the road and go out to fetch a leek from the garden and some onions from the shed. I can hear him pulling on the pair of rubber boots by the door. I can hear him walking down the side of the house, and then nothing until he returns with his vegetables. I hear him chopping vegetables for soup. Hear the rattle of the pot on the stove and, once the soup is ready, the scrape of chair legs on the kitchen floor. A little later, I hear the gush of water through the pipes as Thomas washes his plate in the kitchen sink, then I hear him putting the plate back in the cupboard before going to the living room. He spends his evening reading Jocelyn Miron’s Lucid Investigations, and it’s almost midnight before he switches off the hall light and goes upstairs, but that is a while off yet, the evening is just beginning. Thomas is getting changed in the bedroom above, and I am remembering a long succession of November days that have begun to run together in my mind. There are 121 days to remember. If I can.

To begin with, the eighteenth of November was in no way unusual. I woke up in my hotel room at 7:30 and went down for breakfast half an hour later. I spent the day visiting various antiquarian bookshops in the area around Rue Almageste, calling in along the way at Philip Maurel’s shop at No. 31. Philip’s new assistant, whom I had not met before, thought he would be back toward the end of the afternoon, so I said I would pop in again around five o’clock. At the different bookshops where we normally buy things when we are in town, I found a number of the works I was looking for. I stopped in at one dealer’s in the Rue Renart to look at the copy of Histoire des eaux potables that Thomas had found for sale and that one of our customers had made numerous inquiries about. It was a very nice copy, so I bought it on the spot and put it in my bag, to be taken back with me to Clairon-sous-Bois the very next day for Thomas to forward to our impatient client. At the same dealer’s, I found a couple of other works, which I bought and asked to be sent to Clairon, and in another I picked up a copy of Thornton’s Heavenly Bodies in good condition and containing two plates included only in this one edition, published in two small printings in 1767.

Just before five o’clock, I descended the steps to Philip Maurel’s shop again. It had been a while since I had seen him, six months, maybe more, and we sat for a while chatting at the big desk in the front of the shop, with Philip getting up every now and again to serve a customer or to answer the phone. I told him about the house in Clairon-sous-Bois, which he hasn’t yet visited, although we’ve been there for a couple of years now. I spoke about love, about the apple tree in the garden, about leeks and Swiss chard. I told him about the autumn floods, about the river that occasionally overflows its banks, and about our business, from which we were at last able to make a living, about the growing demand for illustrated works from the eighteenth century, about the auction and my latest finds. Philip told me about life on the Rue Almageste and his new girlfriend, Marie, whom I had met in the shop earlier that day, about the political unrest that autumn, about the high demand for rare and not-so-rare relics of the past—a trend he had also observed in his own business.

Philip specializes in coins from imperial Rome, a business that, when he first set up shop as a very young man, most of his friends regarded as a bit of a joke, but which in recent years has proved to be a lucrative concern. He told me in wonder how, on several occasions, he had been invited to dinner by one of his regular customers only to find himself at the center of an interested crowd consisting not only of elderly gentlemen, but also of younger men and women, all eager to hear about imperial mint regulations, the details of coin-pressing techniques, or about somewhat suspect Belarusian coin discoveries. He spoke of hosts who would suddenly whisk visitors off through their vast Parisian apartments to show off a coin collection, not to the surprise or embarrassment of their guests at their host’s weird hobby, but to their delight, studying their host’s latest acquisitions intently through powerful magnifying glasses. Philip confessed that he had been rather surprised to see his own quiet passion receiving so much attention. These small metal tokens from a bygone age had apparently become the subject of a new collecting mania—not exactly a wave, perhaps, but certainly a growing interest, of which he was keenly aware, in his business.

We reflected a little on this demand for trophies from the past, and I showed Philip my copy of Histoire des eaux potables. We talked about how keen the buyer had been to get hold of it and wondered why someone would want to buy a book like this. Who buys an over-two-hundred-year-old book on the history of drinking water? A collector of some sort, but what exactly his collection consisted of and how the book was to figure in it was hard to guess. I knew nothing about him except his name, his address, and the sound of his voice on the phone when he had called for the third time, a few weeks earlier, to inquire about the book. I assumed him to be a middle-aged man, and I knew that he had purchased two or three other books from us before, although I couldn’t remember which ones.

I still remember how we discussed with a certain irony and detachment this burgeoning interest in the treasures of the past. Although we too could be said to suffer from this same nostalgia or hunger for history or whatever you want to call it, we were both slightly surprised that it was becoming more widespread. I think we almost felt the urge to apologize for our strange interests, which we now evidently shared with more and more people. Well, at least we had managed to make a living out of them. They were our businesses, not a hobby or a fleeting fad. We had our companies, T. & T. Selter and Maurel Numismatique, to manage, and we felt, I suppose, that we had a somewhat more pragmatic relationship with our inner nostalgist than our customers.

Fortunately, Marie turned up in the middle of this conversation. Philip introduced us, we exchanged a few words about the current conversation and also about our having met each other earlier in the day. After a little while, Marie pulled up a chair and sat down at the counter while Philip went out to pick up some food and a couple of bottles of wine from a nearby shop.

It was one of the first cold November evenings. There had been a rain shower in the morning, the rest of the day had been cloudy with the occasional sunny spell, and it was starting to feel quite chilly in the shop. In the little kitchen at the back, where Philip had also slept for the first years after opening the shop, he had an old gas heater, which Marie and I decided to try to light. Marie wiped a layer of dust off the top and together we managed to maneuver the large blue gas cylinder sitting next to it into the back of the heater, attach it, and push the heavy appliance through to the front of the shop and over to the counter. We found a box of matches in a kitchen drawer and lit the gas. By the time Philip got back, the shop was warming up nicely. We sat around the counter and spent the next few hours eating, drinking, and talking.

What I remember most clearly from that evening is how much I enjoyed sitting there between Philip and Marie. They had a closeness I could not help but notice. Not the sort of unspoken awareness that shuts other people out, the self-absorption of a couple, in the first throes of love, who need constantly to make contact by look or touch, or the fragile intimacy that makes an outsider feel like a disruptive element and gives you the urge to simply leave the lovers alone with their delicate alliance. They had an air of peace about them, Marie and Philip, which reminded me of the time, five years ago, when I first met Thomas. The sudden feeling of sharing something inexplicable, a sense of wonder at the existence of the other—the one person who makes everything simple—a feeling of being calmed down and thrown into turmoil at the same time. Philip and Marie had clearly decided to spend the rest of their lives together, it was as simple as that, so what could they do but see what the future would bring. Seen in that light, my visit was a perfectly normal occurrence, I was an ingredient in their life together, a colleague of sorts and a friend, married to one of Philip’s friends from his early teens. I was not in the way, I was neither a help nor a hindrance, neither an opponent nor a supporter, neither a buyer nor a seller; I was simply a fact in their lives.

I no longer remember the details of the evening’s conversation, but I remember the atmosphere in the room. I remember at one point sitting there, studying a corner of the big old oak desk we were sitting around, which functioned as the shop’s counter. I remember the marks in the wood and a little display of coins in transparent boxes, which we had to push to one side to make space for the plates and glasses. I also remember the warmth of the room and my accident with the gas heater. It happened some time after we had finished eating. I had pushed my chair back a bit, but the heat was almost overpowering, so I got up to move the heater a little farther away. I remember Philip had picked up our plates and gone out to the little kitchen at the back of the shop for a corkscrew to open another bottle of wine, and I remember saying something about how hot it was and that I would just move the heater slightly. Marie got up, but I had already placed a hand on its upper edge and given it a firm push away from the desk.

While we’d been sitting there, the heater had, of course, become red-hot, and the metal edge on which I had laid my hand was scorching, so just as the heavy appliance started to shift, I felt a sudden, searing pain in my hand. I let out a cry, an expletive probably. Marie came over and managed to move the heater while I stood there, paralyzed for a moment by the pain. Having deposited our plates in the kitchen, Philip promptly reappeared with a bowl of cold water into which I plunged my hand, and for the rest of the evening I sat like that, with my hand immersed in a bowl of water, although this did nothing to ease the pain. That was the only unusual thing to happen that night.

I got back to the hotel just before eleven o’clock and shortly after that I called Thomas. He had been engrossed in Jocelyn Miron’s book and sounded as though he hadn’t been expecting me to call. I don’t know whether I had disturbed his reading or whether he was glad of the interruption, but I remember how he filled me in on the central themes of the book and explained the different forms of Enlightenment thinking outlined by Miron. I remember too that we discussed the book’s rather odd subtitle, “Rises and Falls of Enlightenment Projects,” and then I told him about my visit to Philip Maurel, about his girlfriend, Marie, and their obvious love for each other, about the growing demand for Roman coins and my accident with the heater in Philip’s shop. Thomas told me that it had rained for most of the day, apart from a break of a few hours in the afternoon. He had taken letters and packages to the post office and later, when the sun had broken through, he had decided to take a walk through the woods and along the river. He had gone as far as the old water mill, thinking that the rain had passed, but on the way home he had been caught in a heavy shower and got absolutely drenched. I remember how we talked about the risk of the river overflowing. He had said that, judging by the height of the water, if the weather forecast for the next few days held good then the danger of flooding was over for now. I don’t recall all the details of our conversation, but I’m sure I reported on the day’s finds, on prices and delivery arrangements, and I know we discussed my plans for the following day, the nineteenth, when I was due to meet Nami Charet at Bibliothèque 18.

Once or twice during our conversation, I complained about the still-painful burn on my hand and we had a little laugh at my thoughtlessness: it wasn’t the first time I had come to grief for not heeding, as Thomas put it, the basic principles of cause and effect. He suggested I get some ice cubes to cool the wound, and then we probably exchanged a few inconsequential remarks. I remember one of us observing that we were slipping back into our old familiar audio-link mode, murmurings that accentuated the distance between us, and before we said good night a couple of times and hung up I think I promised Thomas I would go straight down to the hotel lobby for some ice cubes. That was the last time I spoke to Thomas before time fell apart.

I lay awake for a while, half an hour, maybe longer. I had got hold of a bag of ice cubes, laid the ice on the burn, and wrapped a towel around my hand. The pain and the cold kept me awake, and I tossed and turned a bit, feeling strangely restless in bed, but gradually the chilling effect or the tiredness or whatever it was caused the pain to recede and when I eventually fell asleep it was with a towel full of melting ice cubes around my hand and a small stack of books on the desk in the room: some notes on birdcalls, an atlas of spiders, a book on heavenly bodies, a work on the history of drinking water, and an encyclopedia of animal anatomy. On a chair next to the bed lay my phone, with the alarm set for 7:30 the next morning. Over the back of the chair hung a dress, a sweater, and a pair of tights, and on the floor were a pair of ankle boots and a large shoulder bag containing an extra dress, tights, underwear, a purse, a bunch of keys, an almost-empty water bottle, and a rolled-up umbrella.

I still have the bag beside me on the floor and the books are on the table next to the spare bed. I am no longer in the hotel, but in our house in Clairon-sous-Bois, in the room overlooking the garden. It is evening and it is still the eighteenth of November. Thomas is in the living room, reading, and soon he will switch off the light and check that the doors are locked. He will go upstairs and when he wakes up tomorrow morning his eighteenth of November will have been forgotten.

This is the 121st time I have lived through the eighteenth of November, and the burn is still visible as a slender scar on my hand. It started out as an angry, puffy weal. This soon began to weep, then a long, brownish scab formed over it. Little by little the scab loosened and fell off, leaving a shiny pink mark. It can no longer be felt and, in a moment, when I turn the light off, it will no longer be seen.

The first two volumes of Solvej Balle’s septology, On the Calculation of Volume, from which this extract is taken, will be published next month by New Directions.

Barbara J. Haveland, who translated from the Danish, lives in Copenhagen.