From “Grand Old Inquisitor,” which appeared in the November 2004 issue of Harper’s Magazine. The complete article—along with the magazine’s entire 174-year archive—is available at harpers.org/archive.

When I left the Republican National Convention, I was in awe and a little depressed, as if someone had told me to go fuck myself, and had told me with a kind of meticulous exactitude that was overwhelming, irrefutable. No particular words had done it. It was their reckless profusion, the ceaseless tide of pointless language churning through Madison Square Garden, crashing against the walls, losing meaning with each dyslogic wave. Politicians have spoken self-serving nonsense since the beginning of time, but this was different: larger, more calculated. Whereas John Kerry at his convention had struggled to create meaning—no matter how stupid, dishonest, or clichéd—George Bush seemed to be plotting its demise.

When I left the Republican National Convention, I was in awe and a little depressed, as if someone had told me to go fuck myself, and had told me with a kind of meticulous exactitude that was overwhelming, irrefutable. No particular words had done it. It was their reckless profusion, the ceaseless tide of pointless language churning through Madison Square Garden, crashing against the walls, losing meaning with each dyslogic wave. Politicians have spoken self-serving nonsense since the beginning of time, but this was different: larger, more calculated. Whereas John Kerry at his convention had struggled to create meaning—no matter how stupid, dishonest, or clichéd—George Bush seemed to be plotting its demise.

Certainly the speeches meant nothing. Yes, the president, with his “calling from beyond the stars,” spoke in the coded language of the Rapture, but the code once broken contained only a single message, which was in fact a meta-message: “I am speaking in code to Christians.” Other combinations of words slipped the bonds of meaning entirely. Did Arnold Schwarzenegger somehow end the Cold War in Austria? Was Bush a war hero? Did Kerry want to destroy America? These were half-narratives, made up of questions so preposterous as to end discussion and possibly even subvert our understanding of what it means to mean something. The real message was not “I care,” or even “vote for me.” The real message, radiating from the podium and echoing through the rafters, was that there was no message.

That soul-negating echo was terrifying to me, and all the more terrifying because it was clearly the result of so much effort. Witting or not, everyone there was a participant. The Garden and its surrounding streets had been converted into a monstrous echo chamber, ring upon ring of technology-laden humanity: protesters with their signs and their chants, New York City cops with radios velcroed to their shoulders, Treasury agents talking into their sleeves, the crush of delegates with their BlackBerrys—and reporters, fifteen thousand of them, writers with their wireless laptops, radiomen serenading their outsized microphones, surly camera crews, bright lights in tow, connected by winding cable to rows of idling vans outside on Seventh Avenue, the microwave dishes on top sending signals to satellites miles above only to be sent right back down again, into countless thousands more speakers and screens, bouncing, reflecting, blending, an overwhelming vortex of absurdities. All of it had been orchestrated with ruthless precision, and you couldn’t say a word about it because if you did it wouldn’t mean a thing.

That spinning sensation was not merely symbolic. It was manifest in the very form of the Garden, itself a massive bowl of concentric rings, and in the constant circling of those rings by the thousands of reporters, politicians, and bagmen gathered there to do their work.

In the weeks leading up to the convention, I’d formed an unconscious and somewhat naïve conception of it as a theatrical performance in which some kind of story—likely offensive to me, but a story nonetheless—would unfold upon the stage. Certainly that was where a story ought to have taken place. There was the brightly lit podium, with its odd cruciform moldings; there was the massive video screen, a waving flag one minute, a gospel choir the next; there were the orators themselves, foreheads shining in the bright lights. But no story. The rest of the show was no different. Before I could process one cheap symbol, the producers were on to the next. Even the biographical video, typically a narrative high point of political conventions, lacked momentum. Indeed, it was composed entirely of still images, panned in the manner of a Ken Burns documentary. Setup, climax, resolution—all the elements of narrative—had become superfluous.

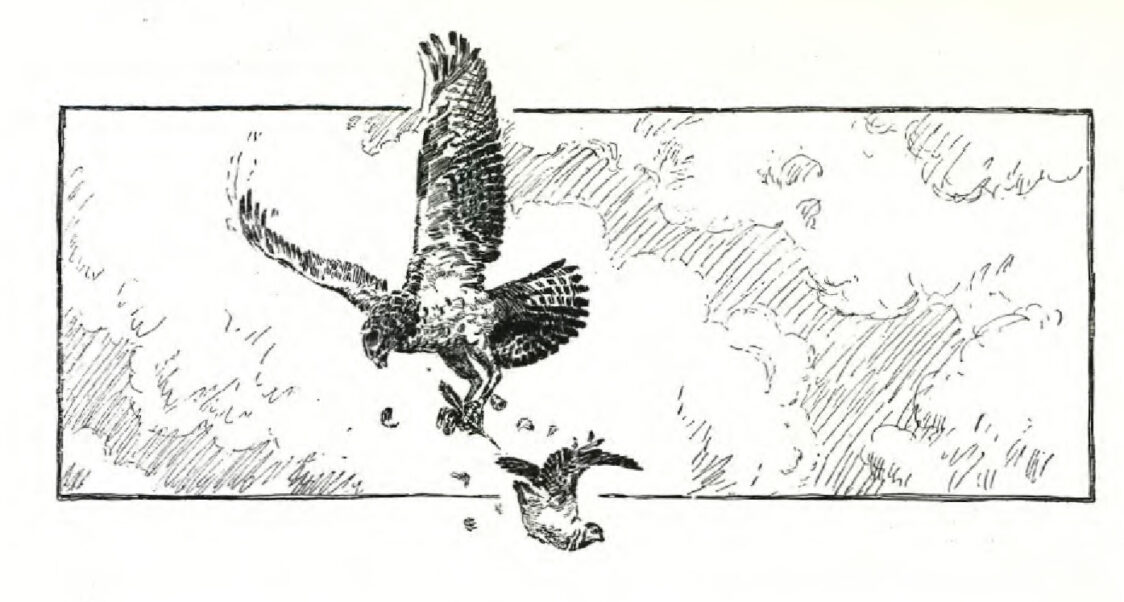

Up along the outer rings my thoughts turned naturally, if dismally, to Yeats and his “Second Coming,” with its rough beasts and its center that failed to hold. After a few constricted circuits of the skyboxes with no real story in sight, I even began to envy the falcon his widening gyre.