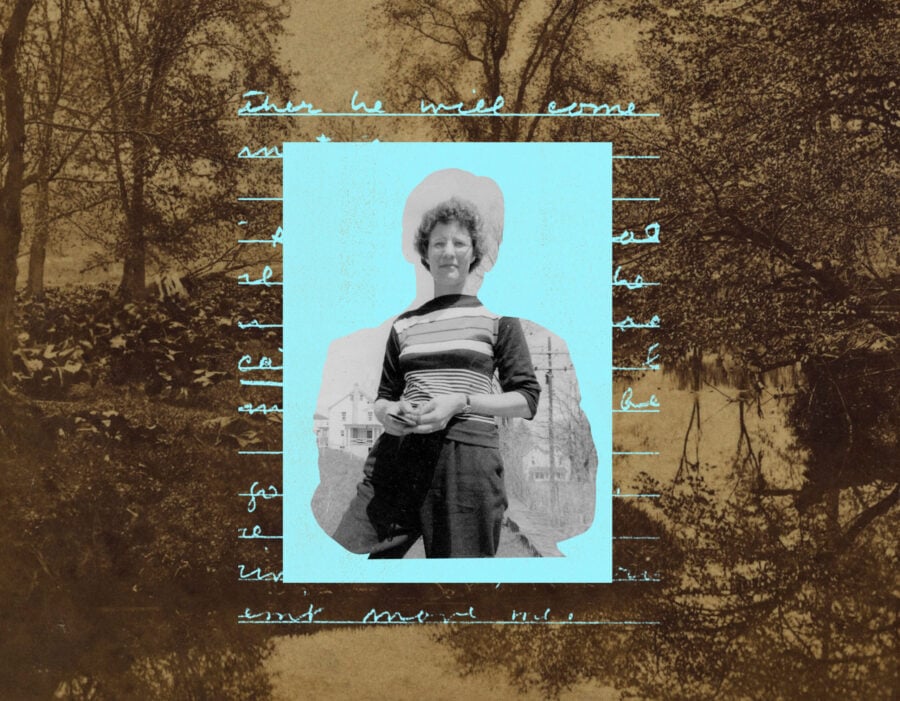

Collages by Lauren Peters-Collaer. Source images of Elaine Rosenbloom and her diaries courtesy the author

Somewhere, Freud remarks that he who is his mother’s favorite will carry that victory with him to the end of his days. I believe this may well be the case for me—but, as many other favored children can confirm, the victory is almost always a Pyrrhic one. How do I know this? Well, in part because I’ve spent the past two years both contemplating the possibility of my imminent demise and writing another novel about my mother.

That’s right—another one. When I embarked on writing this second novel about my mother, Elaine, my wife remarked laconically, Well, finally you…