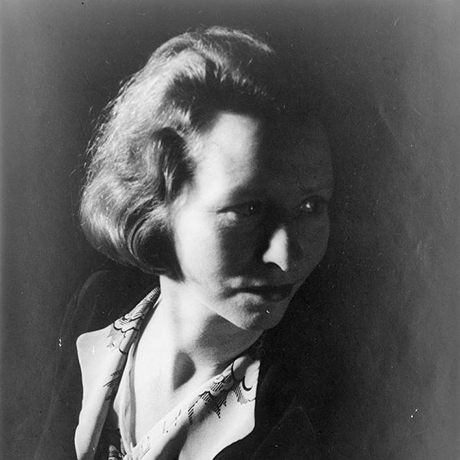

Edna St. Vincent Millay attempted to subscribe to Harper’s Young People, the Harper brothers’ fourth and least successful magazine, in 1902, when she was nearly ten years old, but it had shuttered in 1899. Following her parents’ divorce, she moved in 1904 with her mother and two sisters to Camden, Maine, where she remembered having “twenty-five red books full of knowledge” and all of life’s luxuries, but sometimes few of the necessities. She learned Latin for love of its sonority, read Caesar’s Gallic Wars in the original at age fourteen, and forever carried books of Latin verse with her. At Vassar College, she once told a professor she had fallen ill and would be unable to attend his class. When he ran into her later that day, she explained, “I was in pain with a poem.”

In 1912, Millay submitted the poem “Renascence” to a contest held by the annual anthology The Lyric Year. The editor, Ferdinand Earle, complained of scouring through “piles of disgustingly awful rot” before coming across her submission. “I wrote to ‘Mr. E. Vincent Milay’ to express my amazement at the beauty of the piece,” he later recalled. “It is only after months of correspondence and inquiry that I am convinced that the author is really Miss Twenty Years, saucier and more attractive than ever, tho’ poor as a church mouse.” The poet Arthur Davison Ficke wrote to Earle that “a sweet young thing of twenty” could not possibly have written such verse: “It takes a brawny male of forty-five to do that.” The poem received Earle’s vote, but the other judges cast their ballots elsewhere, and she was awarded fourth place. Some have called it “poetry’s scandal of the century.” “The young girl from Camden, Maine, became famous through not receiving the prize,” one critic wrote. The first-place winner, Orrick Johns, later admitted that he had been given “an unmerited award,” and refused to attend the award dinner: “I did not want to be at the center of a literary dog fight,” he admitted to Millay. “I have $250 that belongs to you, any time you ask for it,” the second-place recipient wrote her.

Millay moved to New York, after her time at Vassar, in June 1917 and quickly entered the heart of a thriving Greenwich Village. She starred in several productions with the Provincetown Players, where she met an early paramour, the writer Floyd Dell. “Floyd,” she would tell him, “you ask too many questions. There are doors in my mind you musn’t try to open.” Dell was later charged under the Espionage Act for editing the socialist and pacifist magazine The Masses, but, after two hung juries, was never convicted.

Millay’s 1920 collection, A Few Figs from Thistles, garnered attention for its feminist themes, and The Ballad of the Harp-Weaver and Other Poems, for which she was awarded a Pulitzer Prize, was released in 1922, the year of T.S. Eliot’s The Waste Land and James Joyce’s Ulysses. She married Eugen Jan Boissevain, of the illustrious Dutch Huguenot descendants the Boissevains, in 1923. Due to severe intestinal pain, she underwent surgery soon after the wedding. “If I die now,” she told her friend Ficke, “I shall be immortal.”

By the end of the decade, her poetry had fallen out of cultural favor. “It is supposed to be fashionable to find Edna Millay’s new volume a trifle disappointing,” the critic Max Eastman wrote of The Buck in the Snow (1928), published amid the early years of modernist poetry’s critical ascendance. “Straightforwardness is wrong, evasion right,” she would later write in a sonnet. “It is the fashion now to wave aside,” a riposte to the likes of Eliot and Ezra Pound. “It is correct, de rigueur, to deride.” Her stature fell further upon her endorsement of American engagement in World War I, when she took a post with the Writers’ War Board, producing such prowar propaganda as The Murder of Lidice, a book-length poem on the Nazis’ destruction of a Czechoslovakian town, and “Not to Be Spattered by His Blood,” written shortly after the attack on Pearl Harbor: “Can I with seething hatred kill him, and return / And be myself, hating no man, / Once he is dead? / Yes. With God’s help, I can.” “I am disgusted with the hollow talk of disarmament,” the one-time pacifist told reporters in 1934. “This is no time to think of one’s reputation when the world is in the midst of disaster.”

Still, she admitted that the poor poetry she turned out for the war effort took its psychic toll on her: she wrote to Edmund Wilson, “I can tell you from my own experience, that there is nothing on this earth which can so much get on the nerves of a good poet, as the writing of bad poetry,” and she soon experienced writer’s block. On October 19, 1950, after a night spent reading a translation of the Aeneid, Millay collapsed of a heart attack—some say she fell down her staircase—and was found in her nightgown by a caretaker, eight hours after her death. She was fifty-eight years old.