A year ago this month, Pope Francis gave a long interview to Antonio Spadaro, the editor in chief of an Italian Jesuit journal called La Civiltà Cattolica. Francis was just a few months into his papacy at the time, and the interview — published simultaneously by more than a dozen Jesuit outlets — was for many people around the world their introduction to the first Latin-American pontiff. The interview is long and complex, but a few words were quoted everywhere. “We cannot insist only on issues related to abortion, gay marriage and the use of contraceptive methods,” Francis told Spadaro. “When we speak about these issues, we have to talk about them in a context. The teaching of the Church . . . is clear and I am a son of the Church, but it is not necessary to talk about these issues all the time.”

Two nuns watch Pope Francis celebrate mass in St. Peter’s Basilica on his first day as the new pontiff © Dan Kitwood/Getty Images

This may not sound like much — it was, after all, a shift in emphasis, not in doctrine — but coupled with subsequent statements about the evil of inequality, the pope’s words suggested the possibility of a new era for the Church, one in which economic justice would take precedence over divisive social issues. Perhaps the most important change was tonal: the punitive, absolutist cadences of John Paul II and Benedict XVI had been replaced by gentle, openhearted language. Progressives both in the Church and outside it celebrated the development. Suddenly, the world had a new apostolic heartthrob: Francis was Time magazine’s Person of the Year and the cover boy for Rolling Stone.

One group in particular may have taken special note of the pope’s remarks. At least since the priesthood was first shaken by the sexual-abuse scandal two decades ago, and perhaps even before then, America’s nuns have been the de facto leaders of the country’s liberal Catholics, especially those more interested in social justice than in holding the Vatican’s line on sexual politics. Like Francis himself, these women have been reprimanded for failing to give sufficient attention to abortion, contraception, and gay marriage. Their choice to focus instead on the needs of the poor has been met with heavy-handed behavior both from Rome and from U.S. bishops. In recent years, two separate Vatican bureaucracies have launched investigations of American nuns. If the new pope were serious about shifting the Church’s attention, one sign might be his treatment of these women. They are a mainstay in inner-city schools and hospitals; they are an important presence in shelters for the homeless and for victims of domestic violence; they minister in prisons and in various venues that serve the mentally ill. They carry the heaviest loads. But a year and a half into his papacy, Pope Francis is looking an awful lot like his predecessors.

The fight between the Church’s male hierarchy and its women religious is nearly as old as the institution itself, but the most recent flare-up occurred during the debate over passage of the Affordable Care Act. The U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops opposed the bill on the grounds that it would require Catholic employers and Church-affiliated providers to cover contraceptive services, including abortion, but many American nuns were vocal in their support of Obamacare. Network, a progressive Catholic lobbying group led by Sister Simone Campbell, sent an open letter to Congress in support of the ACA. Written by Campbell, the letter was cosigned by dozens of Catholic sisters’ groups, including the Leadership Conference of Women Religious — an organization representing the leaders of 90 percent of America’s 59,000 nuns — who asserted that their experiences in their diverse ministries made them uniquely aware of the terrible burden of unaffordable health care. “Despite false claims to the contrary,” the letter concluded,

the Senate bill will not provide taxpayer funding for elective abortions. It will uphold longstanding conscience protections and it will make historic new investments — $250 million — in support of pregnant women. This is the REAL pro-life stance, and we as Catholics are all for it.

The LCWR letter gave a number of Catholic Democrats in Congress cover to support the bill, and President Obama invited Campbell to the ceremony when the Affordable Care Act was eventually signed into law.

The disagreement didn’t go unnoticed. By this time the Vatican’s Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith had begun a three-year investigation of the LCWR, which ended with a censure. “While there has been a great deal of work on the part of LCWR promoting issues of social justice in harmony with the Church’s social doctrine,” the CDF concluded,

it is silent on the right to life from conception to natural death, a question that is part of the lively public debate about abortion and euthanasia in the United States. Further, issues . . . such as the Church’s Biblical view of family life and human sexuality, are not part of the LCWR agenda in a way that promotes Church teaching.

In other words, the nuns were chastised for speaking too little about homosexuality and abortion, precisely the issues Francis believes the Church spends too much time on. The Vatican’s punishment of the LCWR included a stipulation that it no longer meet without the supervising presence of a bishop.

Shortly after the LCWR came under investigation, an “apostolic visitation” was imposed on most American nuns by another Vatican office, the Congregation for Institutes of Consecrated Life and Societies of Apostolic Life. The visitation was to consist of a minute examination of the lives of all American nuns in apostolic communities. It would scrutinize their work, their prayer lives, and, perhaps most important, their finances. This was a rare and serious undertaking, more typically used, as it was in 2009, to investigate such entities as the Legionaries of Christ, a conservative organization whose founder has been accused of drug abuse, molesting teenage boys, and fathering children in Europe and Mexico.

The visitation was made known to the sisters involved by a phone call and a fax an hour before it was announced at a press conference. One person, Mother Mary Clare Millea, the superior general of the Apostles of the Sacred Heart of Jesus, was tasked with collecting the data requested by the congregation; she would have sole responsibility for visiting and reporting on every aspect of every religious community in the United States. Sister Sandra Schneiders comments on this appointment in her book Prophets in Their Own Country:

An analogy would be appointing a single chemistry professor from a foreign university to evaluate singlehandedly all the universities in the United States: programs, professors, administration, finances, libraries and laboratories, admissions processes, graduation and placement statistics, extracurricular activities, student life, etc., judge them all and prepare a secret report for the Department of Health, Education and Welfare on their quality.

The reports Millea compiled remain confidential; those who were investigated were given no opportunity to correct errors or rebut interpretations. Refusing to submit to what they felt was an unjust process, many superiors declined to comply with certain requirements. A few simply attached a copy of their community’s constitution to the congregation’s questionnaire, leaving the form itself blank. When the Vatican demanded a more cooperative response, the sisters sent the blank questionnaires again, expressing gratitude that their constitutions were being read carefully. This was a particularly bold move, for under canon law the Vatican has the right to suppress a religious community. If communities lose their legitimacy, and therefore the right to call themselves Catholic, they are open to asset seizure from the Church.

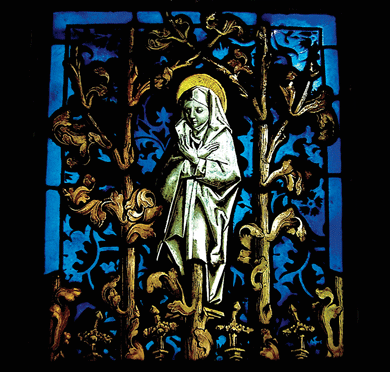

Stained glass depicting Hildegard of Bingen, from the collection of Eibingen Abbey © HIP/Art Resource, New York City.

The Congregation for Institutes of Consecrated Life and Societies of Apostolic Life had claimed the visitation was initiated because of concerns about the quality of the nuns’ religious life and a decline in the number of young women taking vows. But male religious in the United States have also suffered a dramatic decline, without any such inquest resulting. The findings of the visitation have not been made public, and Francis has been silent on the topic.

Meanwhile, the pope has reaffirmed the censure of the LCWR, and a bishop’s presence is still required at the group’s annual meeting. Lifting this mandate would be one way for Francis to signal a real commitment to a more open relationship between the Vatican and nuns. Instead, the new head of the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith, Gerhard Müller — a protégé of Benedict XVI whom Francis elevated to cardinal — recently rebuked the LCWR again, this time for honoring the theologian Sister Elizabeth Johnson with its annual Outstanding Leadership Award. Müller called the award an “open provocation against the Holy See and the Doctrinal Assessment,” because Johnson’s work had been denounced by the Council of Catholic Bishops for its “theologically unacceptable” conclusions. In a statement issued on its website in May, the LCWR leadership sounded conciliatory:

In some ways, for LCWR, nothing has changed. We are still under the mandate and still tasked with the difficult work of exploring the meaning and application of key theological, spiritual, social, moral, and ethical concepts together as a conference and in dialogue with the Vatican officials. This work is fraught with tension and misunderstanding. Yet, this is the work of leaders in all walks of life in these times of massive change in the world.

But while the nuns have committed themselves to asking difficult ethical questions, the Vatican does not seem to feel such a need. The day after his interview with La Civiltà Cattolica was published, the pope, addressing a body of Catholic gynecologists, reaffirmed his implacable opposition to abortion. The first excommunication of Francis’s papacy was of an Australian priest who supported the ordination of women. The pope has appointed as the only American on his committee to reform the curia Boston cardinal Sean O’Malley, who refused last May to attend Boston College’s commencement because the prime minister of Ireland, a proponent of same-sex marriage and abortion rights, had been invited to speak.

O’Malley also prohibited an Austrian priest from speaking to a Boston parish about the ordination of women, and Francis’s own works on that subject were in stark contrast to his wish that the Church be more gentle in its tone and more open to genuine dialogue. In an interview with journalists upon leaving Brazil last year, the pope said: “With regards to the ordination of women, the Church has spoken and says no. Pope John Paul said so with a formula that was definitive. That door is closed.”

In fairness to Francis, it would be asking a lot for him to bring about a complete détente between the Church’s male leadership and its women religious, since hostility of the former toward the latter has been consistent throughout Catholic history. A typical example is Hildegard of Bingen (1098–1179), a composer, poet, herbalist, diplomat, and head of a Benedictine community, who was excommunicated because she refused her bishop’s command to disinter a nobleman buried on her convent’s property. The bishop contended that the nobleman had no right to be buried there, since he himself had been excommunicated; Hildegard replied that because he had been given last rites, the excommunication had been de facto lifted and she would not allow the exhumation to proceed. Not only was she excommunicated but the sisters in her community were forbidden the sacraments and prohibited from singing their prayers, an important aspect of their worship. Hildegard has long been commonly referred to within the Church as a saint, but she wasn’t formally canonized until 2012, when Pope Benedict recognized her as a doctor of the Church.

A portrait of Mary MacKillop at the Mary MacKillop Memorial Chapel, in Sydney, Australia © Greg Wood/AFP/Getty Images

More recent history suggests that hostility toward nuns becomes especially strong when they successfully challenge those who wield power within the Church. The French nun Anne-Marie Javouhey, founder of the Sisters of St. Joseph of Cluny, fell out of favor with the local bishop, who wished to function as the community’s superior, at least in part because he wanted to be in control of its resources, particularly the sisters’ labor. Javouhey traveled to French Guiana, where she became involved in the care of slaves, and, returning to France in 1848, during the February Revolution, became active in ensuring their emancipation. When she returned to Guiana, the French government, realizing that she had the trust of the soon-to-be-freed slaves, put her in charge of governing them. She made provisions for their education and allowed them to marry. The resentment of the local civil authorities, however, combined with the untiring efforts of her bishop in France, hindered her efforts. She was deprived of her sacraments and, understanding that her presence would make the work of her congregation impossible, removed herself from the community she had founded and returned to France.

In 1871, Mary MacKillop, the Australian founder of the Sisters of St. Joseph of the Sacred Heart, was excommunicated by her local bishop for disclosing that a priest involved with one of her schools was sexually abusing children. MacKillop, who was working with twenty-one schools, an orphanage, a reformatory, and a home for the aged and incurably ill, was forbidden to have contact with anyone in the Catholic community. A local Jewish family took her in, and it wasn’t until the bishop made a deathbed admission of his error that privileges were reinstated. She was canonized in 2010.

Margaret Anna Cusack (1829–99) was born a Protestant and converted to Catholicism. She began her religious life as a contemplative nun, writing several books on Catholic themes before turning her attention to the political situation in her native Ireland. Cusack directed her energies toward the plight of the famine-ravaged poor, particularly women. She raised money for famine relief and criticized wealthy landowners, some by name, earning herself both political and clerical opprobrium. She also founded an order, the Sisters of St. Joseph of Peace, dedicated to the welfare and education of poor women. When Cusack moved to the United States to work with immigrant girls, she found an enemy in Archbishop Michael Corrigan of New York, who thwarted her efforts and used his authority to encourage other American bishops to resist her as well. Furious and embittered, she left the Catholic Church and died a member of the Anglican communion.

As American nuns made their way West — physically distant from established dioceses on the East Coast — they became virtually autonomous. When bishops realized what these independent sisters were doing, they deprived them of financial support. In the 1860s, a German community of Benedictine nuns was given money by King Ludwig II of Bavaria to establish a German-Catholic presence in Minnesota. The Church took the money from them and used it instead for the construction of a monastery.

More recently, the Sisters of the Immaculate Heart of Mary ran afoul of the ultraconservative Los Angeles prelate James McIntyre, who served as archbishop of that city from 1948 to 1970 and was later elevated to cardinal. McIntyre believed that the doctrines promulgated by the Second Vatican Council — the ecumenical gathering organized by Pope John XXIII in 1959 — were disastrous for the Church. (He would not allow mass to be said in English in his diocese.) He commanded the sisters to return to dressing in traditional habits and to follow the customary practice of horarium, or fixed hours for communal prayer. Many of the sisters had taken jobs with irregular schedules, and horarium was no longer practical. Having appealed to the Vatican, which backed up the cardinal, the sisters were faced with the decision of whether to obey the cardinal or their own collective wisdom. Most decided on the latter; 80 percent of the 350 sisters opted to be released from their vows and become members of a noncanonical institute — that is, one not officially recognized by the Vatican or the Roman Catholic Church. (This community is still flourishing, and includes both men and women, married as well as celibate.) Approximately fifty sisters sided with the cardinal and formed their own community; the cardinal rewarded them with luxurious living quarters, complete with a swimming pool.

The struggle between Cardinal McIntyre and the Sisters of the Immaculate Heart related directly to disagreements over the liberalizing efforts of Vatican II. This conflict is still alive, and it crucially informs today’s tensions between the Vatican and American nuns. In convening the council, Pope John XXIII spoke of a desire to open the windows of the Church, letting in the air of the larger world. For conservatives, who tend to see their ideal Church as a fortress defending itself against that world, these open windows have allowed much of value to be blown away. For progressives, like the American nuns under investigation, the open windows let in the Pentecostal wind of the Holy Spirit and were an invitation to a mature and responsible relationship with God and the world. The nuns assert that the changes they have implemented in religious life are in conformity with the dictates of the council’s encouragement of women religious to move in the direction of greater responsibility, which entails higher levels of education and self-governance. To this end, they cite “The Nun in the World,” an article written in 1962 by one of the most prominent council fathers, the Belgian cardinal Léo-Joseph Suenens, in which he urged nuns to modernize their dress and to qualify themselves for the varieties of work now open to them.

The cardinals who headed the two offices responsible for the recent investigations of the nuns were of the group that believed Vatican II had done more harm than good. Cardinal Franc Rodé of Slovenia, the prefect of the Congregation for Institutes of Consecrated Life, expressed these reservations in January 2009 in an article he wrote for the Vatican’s official newspaper, L’Osservatore Romano, “From Past to Present: Religious Life Before and After Vatican II”:

we come face-to-face with a necessary and brutal question: Wasn’t “renewal” precisely what we did after the Council? Wasn’t this going to bring us into a new era? And was it not precisely this “renewal” that has landed us where we are today? . . . As soon as naturalism was accepted as the new way, obedience was an early casualty, for obedience without faith and trust cannot survive. Prayer, especially community prayer, and the sacramental liturgy were minimized or abandoned. Penance, asceticism and what was referred to as “negative spirituality” became a thing of the past. Many religious were uncomfortable with wearing the habit. Social and political agitation became for them the acme of apostolic action. The New Theology shaped the understanding and the dilution of the faith. Everything became a problem for discussion.

Rodé’s colleague William Levada, former archbishop of San Francisco, headed the apostolic visitation for the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith. He was noted for marching in protest against gay marriage and criticized for ignoring complaints about clerical sexual abuse. Cardinals Rodé and Levada are close associates of Cardinal Bernard Law, who left Boston because of his role in shielding pedophile priests there. The National Catholic Reporter, the Religion News Service, and the Guardian all ascribe to Law a strong impetus for the Vatican investigations of nuns. He had become an important presence in Rome after he was transferred from Boston and given the prestigious job of archpriest at the Papal Basilica of Santa Maria Maggiore. This transfer enraged many Catholics, particularly Bostonians, who believed Law’s proper place was behind bars.

The Vatican has long been a fertile breeding ground for conspiracy, but the timing of the investigations intersects with other events in ways that cannot be coincidental. The apostolic visitation began in 2008, the year of the first large payoffs connected to the pedophilia scandals, and the total cost to the Church since then has been estimated at $2 billion. Whatever else it is, the sexual-abuse scandal is clearly a crisis of masculinity. It’s all about men and boys. (Girls who have been molested by priests never come into the conversation.) And so powerful women who seem to be taking over traditionally masculine roles, asserting that they don’t need to be subservient to men as in the past, are one more threat to the Catholic patriarchy. What better way to re-establish masculine authority than to demonstrate the ability to dominate women?

The document detailing the purported moral failures of the Leadership Council of Women Religious was distributed in June 2010, just three months after the nuns’ letter to Congress in support of Obama’s health-care initiatives, and was soon followed by the apostolic visitation. No longer could American nuns be idealized as ethereal, silent, obedient, cheerful, and docile, like Ingrid Bergman in The Bells of St. Mary’s, suffering luminously. Nor were they lovably crusty or lovably gooey, like Maggie Smith and Kathy Najimy in Sister Act. The sisters were now important players in the political arena — and they were surprisingly effective.

Many Catholics, tired of being ashamed, now looked to nuns as the face of the Church with which they wanted to identify. And they didn’t like to see the very people who had shielded pedophiles threatening nuns. All over the country, demonstrations and prayer vigils sprang up; nearly 60,000 signatures were collected protesting the disrespectful and high-handed treatment by the bishops. The Catholic hierarchy, imagining that their censure of the nuns would be accepted obediently — if not by the nuns themselves then by an apathetic Catholic laity — were unprepared for the outpouring of outraged sympathy. They failed to understand that the laity’s experience of the nuns who lived and worked among them didn’t conform to the Vatican’s caricature. One sister I spoke to said, “It was as if the head of some international group of firefighters came to a town and said, ‘You know those firefighters that rescued your grandmother from a burning building and gave you CPR when you had a heart attack? Well, they didn’t really do that. They really have set all the fires in the world and caused all the heart attacks.’ Of course people didn’t believe them.”

In addition to drafting the LCWR’s Obamacare letter, Sister Simone Campbell organized Nuns on the Bus, through which she and her fellow sisters traveled thousands of miles across America to protest the cutbacks to social services proposed by the proudly Catholic congressman Paul Ryan. Sister Simone has become a celebrity, not only appearing on The Colbert Report but also addressing the Democratic National Convention.

Sister Simone’s religious society, the Sisters of Social Services, was founded in 1923, in Hungary, as she explained when I went to meet her at Network’s Washington offices: “Our foundress, Margit Slachta, was the first woman elected to the Hungarian parliament. She was a tireless fighter for the rights of the poor, particularly poor women. The community was, from the beginning, devoted to social justice. One of our sisters, Sister Sára Salkaházi, was executed by the Nazis for hiding Jews in the hostel she ran. She was beatified in 2006 by Pope Benedict. They are credited with saving the lives of at least a thousand Jews. The sisters who came to America in 1923 decided to dress in simple gray suits that any ordinary woman might wear. So you see, our commitment to social justice, our not wearing a habit — there’s nothing new about it. It’s what we’ve always done, who we always were.”

I asked her whether she had been frightened when the Church hierarchy turned against her in such a focused way.

“For two days,” she said, “I was completely paralyzed by fear. I just withdrew, and I spent my time praying and contemplating. And then it was over. I wasn’t afraid anymore. I knew I was right, and I believed that what I was doing was under the guidance of the Holy Spirit.

“People ask where I get my courage, but it’s not courage, not really. When your heart’s been broken, nothing can stop you. And living beside the poor, I had my heart broken every day. I think that’s the problem with the bishops. They haven’t had their hearts broken. Most of them have had very little pastoral experience — they became bureaucrats very early on. When you are with the poor, really with the poor, you weep with them, you weep for the world. Weeping becomes part of your prayer.”

I asked her why she retains her commitment to a religious order that is attached to the Roman Catholic Church, an institution whose sexism is obvious, even for some a source of pride.

“Why would I leave a way of life that’s been so fruitful for me, that’s given me so much, that allows me to live in a way that is so right for me? I think that nuns provide an example — well, not just an example but also a way of life that offers things that the world is absolutely hungry for. We offer community, we offer a real spirituality, we know how to listen, we know how to be with the dying. It’s very precious. I wouldn’t let it go. And I’d much rather focus on that than on the famous ‘dwindling numbers.’ It’s not about numbers. It’s about who we are, what we are and can be in the world.”

Weeping, listening, the dying, the poor. These are the words Sister Simone uses when discussing the work of American nuns. Censure, disobedience, investigation. These are the Vatican’s words. Which would Jesus use?