What makes Argia different from other cities is that it has earth instead of air. The streets are completely filled with dirt, clay packs the rooms to the ceiling . . . From up here, nothing of Argia can be seen; some say, “It’s down below there,” and we can only believe them. . . . At night, putting your ear to the ground, you can sometimes hear a door slam.

—Italo Calvino, Invisible Cities

It had been ten years since I had invaded Iraq, armed and dressed to look like dirt. I pulled out my new map of the country as a visitor this time. No targets, no units, no routes given code names as women or beer. I’d spend ten days working my way from Baghdad through Wasit Province to Jassan, a town near the Iranian border. I had served as its provisional military mayor in 2003 but hadn’t seen a single report on it since I left. My hope was to return without revealing that I’d been there before, to travel under my first name, concealed by a beard, to the place I was known only as Major Busch.

On December 9, I boarded a small plane and made the jump from Amman, Jordan, across the angry Sunni provinces, and into Baghdad. As we glided into the city’s variegated glow, I looked for red tracers, bullets fired into the sky. I looked for the war. But we didn’t dive like military transport planes avoiding rockets; we just shuddered onto the surface as a voice welcomed us to Iraq. It was a few months yet before fighters from the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant (ISIL) would threaten the capital.

At passport control, there were two signs, in Arabic and in English: iraqis and others. I stood under my label. We had spent nine years trying to determine which Iraqis we had come to free and which to fight, and we had never really learned the difference.

No traffic from the city is allowed within miles of the terminal, so shuttle vans take arrivals to a meeting area at the far edge of the security perimeter. I sat in the back next to two Syrians and behind four Jordanians, one of whom spoke in a hush while our Iraqi driver examined the currencies and worked the exchange values in his head. He held my ten-dollar bill up to a light before sliding it into a stack of Turkish lira, Iranian rial, and Syrian pounds. I didn’t say a word, my cover already blown by Alexander Hamilton.

The road was empty as we drove, fountains lit in the median with colored lights. Everything was in good order there in no-man’s-land, an immense empty space meant to keep the runways out of rocket range. My interpreter, whom I’ll call Khalil, was waiting in the sequestered lot at the airport’s entrance. He had a cough but, like most Iraqis, continued to smoke. He was dry about it. “If it doesn’t kill me, it would have been something.” He offered me a cigarette, but I declined. “See. Americans get everyone to smoke . . . and then you all quit.”

Khalil always wanted to travel, and it damned him. He worked for the Intelligence Service under Saddam, the only job he could get after school, and was posted to New York City as a United Nations diplomat with the Iraqi Ministry of Foreign Affairs. In 1991, he watched coverage of Desert Storm from his apartment on Manhattan’s East Side while, two hours up the Hudson, I watched as a senior at Vassar College. Because of his connection to the Baathists, he can’t get a visa to move his family to the United States now, despite many years as an interpreter for American forces during the occupation. He will be left in Baghdad as Iraq falls apart.

Traffic was sparse as we drove into the city’s center, where I spent two nights in the Karada district. The storefronts were luminous at the base of dark apartment buildings. There were no police rushing past, no shots fired, just the growl of generators and thump of trucks hitting holes in the road, the cool air thick with exhaust. A radio reported car bombs: eight killed, twenty-two wounded.

“The numbers are all lies in Iraq,” Khalil said. “How many votes, how many dead.”

“How was it here today?” I asked.

He smiled. “Shit.” He was numbed by survivor’s fatigue. The country had all the symptoms of collapse, but the lights were on, international flights were landing, and stores were open as bombs went off. “Even if it’s bad we say: ‘Today is better than tomorrow.’ ”

Traffic filled the streets, and sunrise lit the haze. Flocks of pigeons turned bright as they beat their way above the shadows cast by buildings. Cigarette smoke hung in the lobbies, the clink of small tea glasses ringing like bells. In the alleys wires were draped loose and tangled from rooftops.

Iraq is a place of prismatic identities, the ancient diluting the present, portraits of Shia martyrs appearing on market walls beside crude paintings of Mickey Mouse. There was a time when, despite ethnic and religious conflict, Iraqis were forcibly nationalized. But our occupation labored to ensure that Baathists were criminalized, erased with the declaration that the country was to be a democracy in which they could not participate. Soon people began to see change not as progress but as a steady decline into dysfunction. Many now feel nostalgic for Saddam’s autocratic predictability, and they see their internal conflict as a proxy battle between foreign powers.

A man sweeping the sidewalk said: “Look around. There are only products and politics from other countries here. This is not Iraq anymore.”

A salesman who overheard our conversation added: “What is my country? This is my homeland, but I’ll be a refugee here all my life. I’m a refugee who can vote.”

The street merchants had not yet set up. Congestion and checkpoints delay many motorists for up to three hours, so even at 10:30 most are just getting to their shops. The clothing-stand mannequins are bare, hundreds of plastic torsos hanging on steel bars or wrapped in sacks, legs piled in carts along the curb. Suicide bombers often target crowds in shopping areas like these or cafés where young men gather to watch soccer and play cards, punished for simple pleasures. There were almost no children to be seen out in public areas.

Crews worked jackhammers in the streets for pothole repairs, but the ground underneath was just dirt, sandy concrete shoveled in and leveled, the business of a city sealing its wounds with scabs. Construction was under way everywhere: buildings being chipped down and new ones being poured into rough molds. The quality was so poor it looked like they were erecting ruins. Khalil explained that this part of Baghdad was Jewish until the early 1950s; it is believed the land is still in their names, billions in real estate, but they are gone.

Foreign imports drive the marketplace now. An iPhone 5 is $700, but gas is only forty cents a liter ($1.51 a gallon). The most popular shirts and jeans come from Turkey; fruits and vegetables come from Egypt, Iran, and Lebanon. China is pumping the stores full of cheap merchandise, and though the lore of American quality still exists, the Chinese have found the bottom dollar. This has wiped out most local shoemakers, carpenters, and textile workers. Unemployment is high. Almost no Iraqis have credit cards, so people can spend only what they have in hand.

Every few blocks there was a corner that glittered with tinsel on artificial evergreens. Ranks of inflated plastic Santas smiled with lunatic glee from patches of cotton snow. I asked Khalil whether there were many Christians in the neighborhood. He said, “No. Everyone here celebrates Christmas.”

Billboards showed another world, clean and Edenic. Framed posters of waterfalls were everywhere, fantasies imported along with wide-eyed dolls and stuffed bears. Photo shops covered their windows with studio pictures of children posed on backgrounds that resembled anywhere but here.

The Fourteenth of Ramadan Mosque blared its call to prayer over the whine of police sirens. It stands on one side of Firdos Square, where U.S. Marines pulled down the statue of Saddam in 2003; his bronze feet are still standing on the pedestal. Across the square from the mosque is the Cristal Grand Ishtar, a former Sheraton, where many Western journalists stayed during the war. There were dozens of flags flying in front of it, but the American flag was missing. The absolute absence of Americans anywhere was noticeable. I didn’t see us on the streets, at the airport, or even in the hotels. Our diplomats are hidden in the embassy, our largest oil company is divesting from wells outside of Kurdish control, and our military has vanished.

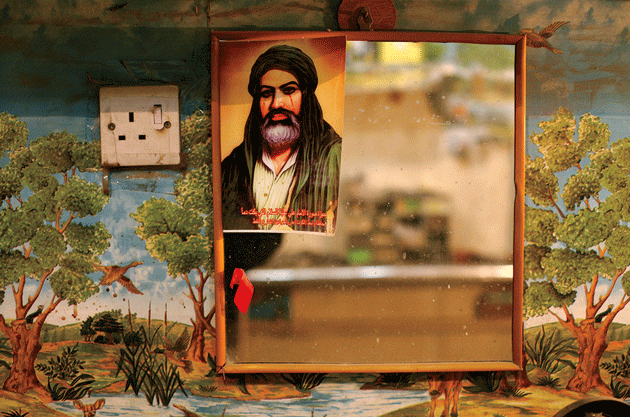

Banners with Husayn ibn Ali’s impassive face colored the streets. He was killed in Karbala in 680 and enshrined there. The pilgrimage had begun, Shias walking to his tomb to mourn his death, targeted by Sunni extremists along their route. Traffic was constant, the jabbing of horns continuous. Iraq looked busy but it did not look happy, a concrete hive filled with families grinding out the day just to make it to the next one. As long as I kept moving I stayed inconspicuous. It was when I stopped that I felt out of place. Iraqis moved around me, purposeful like I had been when I was a Marine.

The door of a corner post office opened into a blackened hole, the inside filled with bricks and trash, wild cats slinking over the piles. It had been hit by a car bomb and had never been rebuilt. I asked how people got letters now, and a snack vendor replied: “Who would write?”

Khalil and I stopped at a café on the next street. In October 2007, another car bomb went off here, killing 230 people, Khalil said. (Official estimates put the number of dead at only twenty-five.) Khalil had lived above the café; his apartment was destroyed and his daughter was badly wounded. He was an interpreter for an American army unit based in Baghdad at the time, and the soldiers came to her rescue after Khalil made a desperate phone call to their headquarters.

Baghdad is a city of armed men and bullet-pocked barricades. The ministries are still ringed with our fortification walls and makeshift watchtowers. Wire, soldiers, and up-armored Humvees are placed at regular intervals. The feeling is of an invisible siege, the awaiting of another inevitable defeat. In 2003 the transition from what Iraq had been into what it could be, though in disarray, was colored by potential. We couldn’t see that instability was going to replace autocracy so completely — and then Nouri al-Maliki’s government brought both. The blast barriers we erected as temporary defenses became permanent fixtures, giant nameless gravestones.

To get to Jassan, we had to go to Kut, the capital of Wasit Province. At a transportation hub on the eastern edge of Baghdad, drivers yelled the names of Iraqi cities as if they were reading from a Shia map: Basra, Najaf, Nasiriyah, Karbala, Kut. The U.S. State Department had been emphatic in trying to dissuade me from independent travel in Iraq, especially so far from Baghdad, but journalists have always come to that city and told the country’s story from its point of view. I needed to see what had become of the distant villages I had known. They had remained intact for centuries because of their political insignificance and isolation. It was my hope that those same qualities had preserved them, so far, from the violence and social collapse of the cities.

Khalil got a cab to Kut for 30,000 dinar ($25 at 1,200 dinar per dollar), and we set out on a route that ran east, above the erratic path of the Tigris. The traffic out of Baghdad moved in jerks, passengers expressionless as they stared into other cars, men in the front and women in the back. We passed a former American base, now Iraqi, and it looked run-down, dirt-filled Hesco barriers sagging into piles, soldiers slumping at their posts. We saw hundreds of flatbeds loaded with rebar for new construction, and there were herds of sheep, pens of chickens, and mesh bags of melons pressed up to the road. Baghdad was being fed from its immediate perimeter like a medieval city. It is a medieval city.

We were stopped and questioned at an elaborate new structure on the border between Diyala and Wasit. It had the design of a triumphal arch, the paved passages through it incomplete and the building still empty. It looked just like a border station between countries. These never existed between provinces before. There was no point. Khalil felt it was preparation for the future division of Iraq.

Boys swirled through the stalled traffic selling boxes of cookies and cigarettes. A heavy man in the passenger seat rubbed beads in one hand, smoked with the other, and spoke as if he had grit in his throat. “Half of us are soldiers, the other half are merchants now. All of Iraq is a shop with a war in it.” The backs of his hands were dark tan, his palms bleached pink. The driver looked like a bird: long, sharp, drooped nose, small eyes, gray leather jacket. He barely made a sound, eyes fixed on the road.

For a few miles, when the river curled close, there were fields of green grass and young palm trees. New brick houses have replaced huts once built from the silt of the Tigris. It was like another climate, a verdant country winding through an arid one, the two sharing nothing but proximity.

Police checkpoints profiled “foreign” Arabs, men from Saudi Arabia and Qatar especially. Muqtada al Sadr was on billboards promoting his religious rank among Shias, his dark glower no longer adolescent. (His Mahdi Army, raised to expel occupation forces, has been reconstituted as the Peace Brigades and is now fighting ISIL alongside the Iraqi army.) Gigante cigarettes posted their own highway signs, photographs of wealthy men smoking. They stood above hovels where laborers squatted by fires, the fumes from burning plastics stuck to the air. Mourning flags waved over homes, and donkeys grazed in trash. Traffic surged after each checkpoint, and we sped along the open road, sparse scrub on the desert side, tall reeds and fields irrigated from the Tigris on the other.

Roadside refreshment stands had been set up with rows of chairs for pilgrims to rest on as they made their way to Karbala. Separate tents were nearby for men and women to sleep in. I asked Khalil whether he had ever walked the route, and he said you only walk if you believe.

In 2003 we advanced from Kuwait to Kut with orders to push all the way to the Iranian border afterward. Most of our maps had nothing but a single road drawn through flat space, our pen marks on the route meaningless to the land. We would piece the maps together as we drove north, passing from one rectangle of desert to another. The terrain was open and scarred by tank trenches dug to guard the only highway from the Persian Gulf to Baghdad. The tanks — Soviet imports — were still there, scorched by air strikes, relics of two-dimensional thinking. In these dirt barrens nationhood was impossible to see: a herd of sheep and a single man, a Bedouin tent sometimes afloat on the near horizon. My unit had been brought from the cold, wet coast of North Carolina late, and we hurried into Iraq far behind the fighting. It was a kind of immediate war tourism, the burned wreckage of our own amphibious assault vehicles still on the muddy shore of the Euphrates in Nasiriyah. Torched and hollow, they sat below the bridge as we crossed, heading north in disbelief. The fires had died out, but the buildings along the river looked long-forsaken: pitted by bullets, windows chewed open, with bricks spilling from the walls. Marines from Task Force Tarawa were on rooftops and street corners, Iraqi women walking cautiously around rubble and wire with their children, in occupied territory.

The war moved entirely along two highways, both regime and coalition forces ignoring small periphery towns, the vast desert and its villages of no strategic importance to anyone. As we approached Kut, Iraqi army uniforms lined the road near abandoned outposts. No bodies or blood, just helmets, pants, and shirts. There had been a large army garrison waiting for the advancing Marines, but they quickly fled or dissolved into the city dressed as civilians.

Today, as our cab arrived at Kut, Iraqi soldiers at the checkpoint wore U.S. tricolor desert camouflage, the same my unit had been issued for the invasion. It was as if the hidden army of Saddam had reappeared wearing our uniforms. They walked carefully along our cab with a fake bomb detector, purchased from a crooked British contractor who resold $20 American novelty golf-ball locators for $27,000 each. Corrupt Iraqi officials bought $40 million worth of them. The soldier stared intently at the indicator light, three years after their sale had been banned, a keeper of the lie. “Everyone knows it does nothing,” the passenger in the front seat said. They scrutinized my passport and visa stamp. “Ameriki?” they kept asking as if it couldn’t be true and then brought out an officer to verify my papers. He walked from the office with annoyed importance and asked where our weapons were. Khalil explained that we were alone and unarmed. The official looked up from my passport, shook his head, and let us go. Ten years ago I might have done the same to him.

My photographs have been kept in an order absent of chronology: a blindfolded skull, a pile of boots, an English gravestone, a child waving. I never labeled them, just expected I would remember like everyone does. Seven months of circumstantial evidence. Military mobile exchanges only sold 400-speed film, meant to shoot subjects in lower light, so the reduced resolution is noticeable when the pictures are enlarged, their definition becoming increasingly granular, as if composed of pressed dust. The imperfection of vision is at work, the flickering of lines, the involuntary squint to identify, exactly, what you’re seeing, the desert going from vast and static to pulsing and immediate, like memory does.

Kut was familiar but disorienting, the streets swollen with shoppers and thousands of pilgrims. The city made the sounds of collision: sharp honks, truck engines, salesmen calling out, and the constant chirp of police whistles. Goats ate the stiff dead grass in the median. The center of town looked battered.

We stopped in at the Iraqi Journalists Syndicate office. All the government furniture was foreign-made, wood glossy with thick lacquer chipping at the edges. Everyone smoked. They couldn’t believe I came by cab from Baghdad with nothing but an unarmed interpreter. A man shook my hand and smiled. He said they have a proverb: “You enter the house from the door, not by the window.” The last American journalist anyone could remember came here three years ago in an armored convoy and only stayed for an hour. The manager said, “There is not enough violence for Kut to be news. You look for stories, and the city doesn’t exist.” Another added, “I would rather not exist than make the news here.”

A man named Nassir took us to see a cemetery built by the British for the men lost in the battle for Kut during the First World War, its headstones, like its soldiers, brought from overseas. It was the only place in the region that commemorated the people most responsible for Iraq’s creation.

Nassir drove in rushes and jolts, stabbing in between cars, everyone around him doing the same, warning beeps constant, lanes filled like blood vessels, everything somehow pumping through. Traffic intensified as we pushed into the marketplace, the streets channeling a reckless braid of pedestrians, motorcycles, trucks, carts, and cabs.

“It’s amazing the roads aren’t filled with car accidents,” I said. “I can’t believe no one gets hit here.”

Khalil interpreted and Nassir laughed. He had a joyful face.

“Happens,” he said, smiling.

He’d been assigned as our official escort for the next eight days in the province and had been cheerful since we arrived. Tomorrow we would hear that he hit a young boy on his way to pick us up, and a cousin was sent with another car to drive us in his place. The child died in the hospital, and we wouldn’t see Nassir again as his life became suspended between tribal atonement and court. But today he was happy to be on a journey with the only American in Wasit.

We went to the souk, which was easily three times the size it had been in 2003. Even then the market had been a kind of neutral space, uninterrupted by invasion or regime, the stalls passed from generation to generation. Trade was conducted in dinar notes stamped with Saddam’s victorious image or in dollars stamped with our own Founding Fathers. Under Saddam, an Iraqi soldier made the equivalent of $120 a year. By 2004 the Coalition Provisional Authority desperately rehired them at a salary of $400 a month. There was immediate, irreversible inflation. Corruption in the military bloomed as soon as wages did. An Iraqi soldier makes $1,000 a month now.

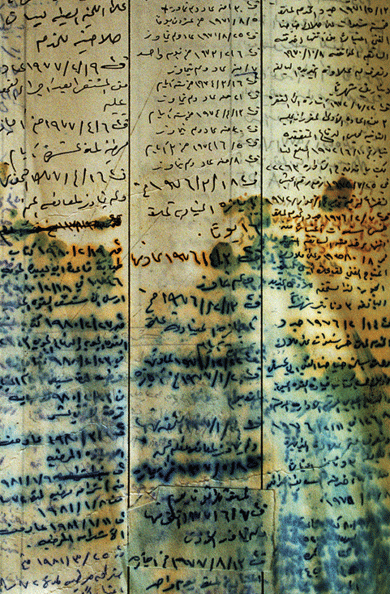

When I first walked through the market in 2003, the concrete pillars in the central square were covered with xeroxed posters of the people “disappeared” by the regime. A week later, near the Iranian border, we would watch as some of them were exhumed from the site of their execution.

Today we passed through groups of women in black, children emerging and retreating beneath their parade of robes, salesmen with handfuls of cash manning caverns of cloth, sandals, and spice. We arrived in the street where the Kut War Cemetery lay. There was a new fence in front, but the rear wall had been pushed down, exposing the site to the city. The concrete cross still stood, but it looked changed, some graffiti spray-painted on it, the U.S. Marine rededication plaque torn off. Children played on a worn dirt clearing where headstones had been, kicking a ball over the soldiers below, one of them digging on the surface with a little toy shovel. Phragmites reeds had overgrown the rest of the lot. The owner of a nearby shop said it had been used as a dump but the Americans cleaned it, and for a while it had flowers and a guard. The guard went unpaid, he added, and “kids” took the headstones and sold them in the market. The cemetery was a dump again.

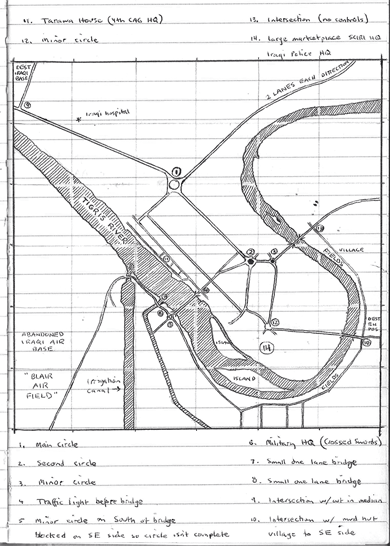

U.S. satellite map found, following a sandstorm, in the ruins of the Iraqi base it depicts, near Kut, 2003

“Many groups have come to study the cemetery since 2003. The Americans built a new fence to replace the British one. Then the British built one to replace the American one. They all look for the missing stones, but they find nothing. They ask questions, take pictures, and leave. Just like you.” Just like me.

Outside Iraq, Kut is a city remembered only as a military disaster. The British had marched a colonial Indian division up the Tigris toward Baghdad but were stopped by the Turks and their Arab allies at Ctesiphon and sent into a retreat that ended here. For five months they were trapped by siege, unable to resupply or escape, pounded by Turkish artillery, finally surrendering at a loss of 12,000 men. Only 420 have graves here; the rest are buried somewhere underneath the city. I waded into the dense stand of reeds and found a few toppled headstones still largely intact.

1525 private

w. hoskins

somerset light infantry

24th november 1915, age 20

lord remember me

when thou cometh

into thy kingdom

The reeds stood ten feet tall and were plumed with clouds of seeds. I watched them sway above me while crouched by a grave in their shade, a cat passing by using the line of fallen stones as a path. It was my birthday, and I thought of all these soldiers, their entire lives marked by nothing but the day they died and now marked by nothing at all. I emerged coated with dust, my hair downy with silky seeds. Khalil had been pacing the perimeter, calling to me every few minutes as if I were lost in the wilderness.

Outside the gate, I noticed some bright fragments tamped into the gutter and recognized the elegant carving of a wreath in marble, the crest of a gravestone sunk into gray drain water. Men watched as I took a photograph. They followed as I went up an alley and found an entire headstone facedown in concrete used as a step into a gated courtyard. It showed no sign of damage or wear, dug up unbroken precisely for this purpose and moved a mere fifty feet from its grave. Another photograph and Khalil suggested we hurry. A small crowd was gathering. As we left I found more stacked as a stoop in front of a shop. Then, embedded in the street itself were five stones used to fill in potholes, carts rattling over them, a carved cross facing up. I kicked aside trash and drew attention from nearby vendors, who wondered why I was so interested in the pavement.

In contrast to the forlorn British cemetery, the Ottoman memorial is proudly guarded by an Iraqi Arab paid by the Turkish Embassy. He is the fourth in an unbroken line since his great-grandfather dug the graves. He greeted me with his young son beside him, the next guard. Polished plaques on the gate say turkish martyrs, 1914–1917 in Turkish on one side and Arabic on the other. The white concrete markers inside bear no names, just the raised Turkish star and crescent, dabbed red with too much paint. These fifty Turkish soldiers and seven commanders are all that can be found, representatives of 10,000 lost here. I asked where the rest are buried and the guard swept his arm around the horizon. Iraqis are not interred in Kut. They are carried to the city-size cemeteries in Najaf and Karbala. Only invaders are buried here. The caretaker showed me the visitor’s log, and it was a list of foreigners, mostly Turks. I added my name. On our way back to the car Nassir bought diapers for his new baby. Today is better than tomorrow.

We checked in to one of the two hotels in Kut, and it was unfit for prisoners. They made a copy of my passport visa for the Iraqi police. The state now tracks all guests in hopes of catching foreign terrorists who have no family and nowhere to stay. Guests in hotels are all suspect. Despite the thousands of pilgrims passing through Kut, the hotel was almost completely empty. We tried to find a restaurant but failed to please Khalil after two cab rides. He was suspicious of all the kebabs since meat is no longer inspected and regulated like it was under Saddam, and some places will secretly serve donkey. (If there is anything an Iraqi disrespects more than a donkey, I’d like to know. I remember a police officer wiping his hands and saying, “Saddam Donkey,” as the highest sign of his disgust.)

I lay awake most of the night, feeling insects real or imagined, seeds from the cemetery still in my hair, the bed uncomfortable and heat up too high. The ventilation fan didn’t work, pigeons nesting in it, septic gas seeping out of the bathroom and smearing the air in the room. Unlike Baghdad there was no security curfew in Kut, so the sound of horns and police whistles came through the coo of birds all night. A loose wire kept a long fluorescent light blinking, the mint-green paint on the walls appearing and disappearing in flashes. Everything was worn down and dirty like everything else in the city.

In the morning, after being locked in our room by a broken latch, we waited to meet Mahmoud Talal, the governor of Wasit, in a building notable only for a sign in the lobby that Khalil translated as: “Don’t torture your children.” Men waited with papers, their needs requiring the brief review of government. Some strode through with an obvious sense of privilege, family of the governor or officials of note.

We were finally invited into the governor’s office, a large empty space with ornate chairs pushed up against the walls. He reviewed and signed documents, pausing to speak with us, his attention often drawn to men bringing messages whispered to him. He answered questions with the neutrality required of his position, the room listening carefully. I asked about the British cemetery, and he said it had been reported to the British Embassy but they had done nothing. I asked about the arrest warrant issued by Maliki against Sunni members of his Provincial Council, and he regarded his audience. “That is just political propaganda,” he said. I responded: “It is very effective political propaganda.” Everyone laughed.

The area around Kut had become dangerous for tribal sheikhs. Notable men were said to be targeted by Al Qaeda now because it was big news and reflected poorly on national security. It was believed that Sunni extremists were attacking their own to frame Shias and encourage sectarian violence. But Kut was rarely the target of bombings. Most of Wasit’s own security forces had been sent to the mixed city of Suwayrah, near Baghdad, which had been especially unstable. Governor Talal was trying to preserve the support of his Sunni minority while Maliki was estranging them. I found out later that a sheikh sitting in the room was from Asaib Ahl Al Haq, the violent Shia militia allied with Maliki. They had attacked Americans for years. He was a very dangerous man who smiled benignly while I questioned the governor and radiated consequence as he responded. I was the only one who didn’t notice that he was silently presiding over the conversation. It must happen all the time. The man who confided this to us said, “We can’t make him leave.”

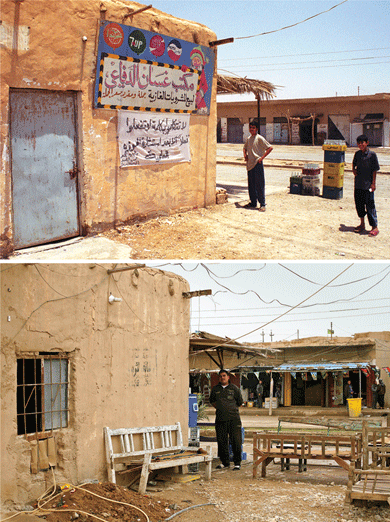

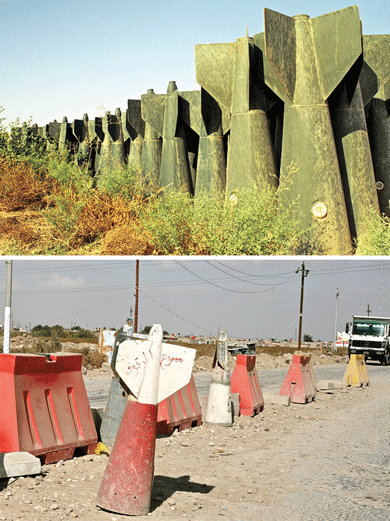

Bomb fins on the Iraqi air base at Kut in 2003 (above), and repurposed as traffic cones in 2013 (below)

After the interview Khalil and I were invited to stay in the governor’s guest house, a kind of overwrought hostel for officials visiting from out of town, and we were very grateful to leave our miserable hotel. Our new room could have been anywhere in the world. The bedsheets had pour les amoureux du café printed on them, and the furnishings still wore plastic wrap as if their newness could be preserved, the desert dust kept off for one more day. An ad for a Saudi falconry contest played on the TV, the only clue that we weren’t somewhere in Mexico, and most channels showed American movies.

Back out in the city I traced the edge of the Tigris and came to the souk from a new direction as night fell. The air was damp and smelled of fresh bread.

One shop selling uniforms for security forces displayed the modern U.S. Marine desert digital camouflage, usmc in tiny letters embedded in the pattern. They can only be purchased with an official government ID, and the vendor showed me the logbook in which each purchase was recorded. A T-shirt had the misspelled slogan if everything is exploding around you. “thrt’s probably us.” At a tailor’s shop, portions of shirts and pants were pinned to the wall. They looked like men blown apart, clothing for the bare dismembered mannequins piled on the streets of the Karada district.

The American memories of Iraq are largely urban. Drawn into population centers where people and religion rubbed against each other, our experience became associated most with the names of a few cities. The villages spun away in an expanding orbit, growing more distant from us, and from Baghdad.

The floodplain between Kut and Jassan was covered with winter rainwater, a gray sea reflecting the cloudless atmosphere. As we rode out the next day, the horizon was without distinction, above and below nothing but a singular color, the sky spilled onto the desert. The land here betrayed no proof of an underneath, no outcroppings of bedrock, no hills and no sedimentary layers distinguishable in the dust. It seemed to be of an almost infinite depth, the soil going down for miles, all the way to oil.

Stockpiled aerial bomb fins we once found on an abandoned air force base in Kut were now painted white and used as traffic cones at checkpoints everywhere. We saw buses full of Iranians on their way to Karbala, a sign of tremendous change here. Our cab driver said that once, a few years after the Iran–Iraq war, “they found a candy wrapper made in Iran and the whole area was swept by the military looking for the Iranian who dropped it. All the way from Kut to the border. There was no border traffic before the U.S. invasion. Control by the Iraqi military was absolute.”

The road was lined with blown tires or the rusted steel rings of burned ones. We stopped to visit Bedouins camped along the route. A man from a nearby hut guided us across a ditch to a tent. His wife immediately called his cell phone, afraid that we had taken him. He smiled as he explained her worry. “In Iraq many men have been taken. Walk off like this with unknown people and never come back to the wife.”

Sheikh Sha-lan Debon invited us in for tea. Inside his tent there were two sitting rugs, a small ring of raised clay for a fire, plastic containers of water, and a pile of dry branches. The camp is moved every five days. The camels they raise sell for between 400,000 and 500,000 dinar in Najaf. There was government land for grazing during the regime, but now it’s all privatized and he has to pay rent. His herd is shrinking every year. “The old map should be honored,” he said. When I asked if he had a copy of it, he said, “Of course.” I asked if I could see it, excited by the discovery of the elusive tribal map of the desert, but he just smiled and pointed to his head. A cousin handed me a cup of tea. They have a saying: “Drink your tea and all will be fine.”

Debon said he is in charge of a thousand men. I asked how many women, and he scoffed. “I don’t know. Women come and go in the tribe. Men stay.” The tribe is spread over hundreds of miles, from Basra to Babylon, and he coordinates all of it by cell phone. He has no radio, television, or Internet. “Everything is by speaking.” He takes his flag to funerals or has it taken in his name. A sword and a crescent. He just went to a funeral in Ramadi, where a Sunni rebellion was taking form. I asked whom the tribe sides with now. “We have no enemies,” he said.

He was disappointed by the end of reliable food rations. During Saddam there were monthly allotments of flour, sugar, oil, milk, tea, and beans, but now there is only flour. “If the Americans had stayed or had not come it would be better,” he said. Six of his family members have recently tried to join the police. No success. They participated heavily in the military and police forces during Saddam’s regime. “Without family in government we have no connection to it. We are not represented with anyone we can trust. So we have no government. No state.” The Bedouins had always been considered stateless, but now they longed for one. They voted for Governor Talal. He visited them in their tent and in Jassan but they haven’t been able to see him since the campaign. “A good man, maybe only for election. Ten years electing people and we get nothing.” He said they join no parties. Anyone who does gets fired from the tribe. He’s had to fire some.

Criminals are also expelled. If guilty of murder they are exposed to the judicial system, but traditional law runs parallel to state law — tribes meet and blood money is paid or people are forced to move. It is most important for the tribe to go to the person bringing the charges and try to handle it out of court. Just yesterday he had to negotiate such a dispute. “Najaf people’s car hit one of our tribe — killed. Ten million dinar if someone kills on purpose, but this was accident. My tribe asked for nothing.” I thought of Nassir. The American military generally paid $2,500 to families for civilian deaths caused by military operations in 2003. It was considered a small fortune then.

“Once, everything here moved by camel. Bedouins were first in society. Now we are the poor and soon camels will only be in zoos. Where will we go when all the land is owned?”

One of Debon’s family members invited us to his house by the brick factory. Khalif Milbus is married with fifteen children, and his elderly mother lives with him too. No government support, and the area is off the electrical grid. “Since always there has been a problem with power,” he said.

“Electrical power or political power?” I asked. He smiled.

“Yes.”

Regular blackouts continue throughout Iraq, towns darkening and then flickering back as private generators are tricked on. I heard the same two words everywhere in 2003: “Maqqu kaharlabbah” (We have no power). It is slang born from decades of corruption and savaged or inadequate infrastructure.

Milbus’s sons did not see herding as their future. Zaid wanted to be a teacher; Aneed, a doctor. His eldest son left school to work in the brick factory. He didn’t mention his daughters. They will marry one day. Milbus served in the military “from 1988 until Bush the Son released us.” He was paid no salary, so he had to escape service to earn for his family. If he had money he would buy a tanker, a truck, a tent, and camels. “I would not stay in this prison house.” He would “travel Iraq as a true Bedouin” again. I asked whether he fears the Bedouin way will end in Iraq? “Yes. It is almost destroyed. Not much left. Someday men will not know the sun or the land. Only roads.”

At the brick factory, a kiln the size of a warehouse was filled with ruined bricks. The fuel supply was inconsistent, and they didn’t bake properly. Weeks of labor and 260,000 bricks lost. The tall stack blew smoke in a trail thick enough to cast a shadow on us. I stood on the hot roof of the kiln looking through the heat at the burned land. Boys ran, kicking a soccer ball, their lungs filling with soot.

Beside the factory is a settlement constructed of discarded bricks. There were women there, and I was cautioned not to take any photographs. They were all squatters who worked at the factory, dead poor, a sewage trench the color of oil running past their homes. I asked Milbus whether he had any family living there. He replied with scorn that he would “never allow his women to live like this.”

When we got to Jassan it was almost unrecognizable. A new colony of a hundred two-story brick homes had been built along the road. In 2003 the entire village was on a hill. It was ovular, organic, interdependent, and defensive in its construction. Its dirt walls had been kept smooth for a thousand years by the vitality of dense occupation. Now it was beginning to wear down, roofs collapsing and spring rains washing the mud away as families resettled in the brick buildings on the plain. The spreading construction was gridded, edged, and fragmentary, suburban seeds of a new order. They seemed to belong to a different people, the tight rural community broken apart into solitary satellites.

While waiting to meet with the town councilmen on the new central street, I asked a policeman why so many people were moving to Jassan and building houses. “Loans,” he said. “Ministry of Financing and Housing gives them now. Thirty million dinar. Free for a while, then monthly payments. No new people moving here. Everyone is from the hill.” It seemed improbable that there could be so many, but the population in the old catacomb of homes on the hill had always been impossible to guess from the outside.

We were invited to meet in the city manager’s office, recently built across the street from the old city-council building and jail my unit had restored in 2003. They looked old and smaller now in comparison with the new buildings, diminished in scale. Mr. El-Timmimy Hawas, district manager, greeted us and then worried how his tie looked when he saw my camera. He said there were no problems with the Americans, just disappointment. “When coalition forces came, Iraqis heard they would get whiskey with the rations, but all they brought were blades.” He said the Georgian troops who were last stationed here were all right also. “They stayed to themselves, which was best.” Ukrainians before them had caused some trouble when they restored a clinic and painted their flag over the entire exterior. “We didn’t want another flag on us.”

Their problems were few in comparison with those of the cities. A drought had dropped the level of the Tigris, and the pipe that drew from the river could no longer reach it. The lack of rain had also stressed herds and palm orchards, but the farmers were still keeping them irrigated. They have three clinics but no doctors or surgical wards. Pregnant women and serious injuries must go thirty-one miles to Kut. They had asked the Provincial Council for aid to expand, but the budgets are based on population, and Jassan, despite administering eight other little desert villages, has only 12,000 people. With an annual budget of about $1.7 million (around $140 a person), they can do only so much. Turkey is contracted to build them a new water pipeline from the Tigris, and a water-purification plant is being built right across the highway from town. They also won a Japanese grant to upgrade the aging Soviet pumping stations.

We headed over to meet Ali Talib Muhammed, a councilman from the original 2003 city council who has kept his post since. He is an exceptionally solemn man. We had met many times while I was stationed in Jassan, but now he didn’t recognize me. With a beard, a pen, clothing from the street in Baghdad, and ten years, I was transformed, detached from their memory of who I had been when I wore a pistol and a rank.

Muhammed recounted the village’s response to our invasion. Saed Khalum was the most respected man in Jassan in 2003, and on his own, he had assembled a council before coalition forces had even arrived. I met them on April 29, thirteen days after their first town meeting, when my unit moved up from its position farther south along the Iranian border. Two years later, on May 30, 2005, the Provincial Council officially acknowledged them as the city council, and they received their first salary. By then I was on my second deployment fighting Syrians and Sunni extremists in the city of Ramadi on the other side of Iraq. While in Jassan this time, I met nine of the original eleven councilmen.

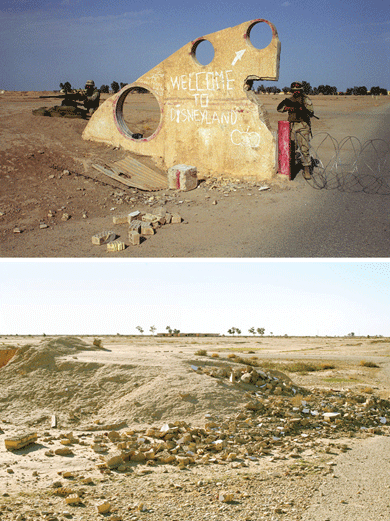

Marines guard the entrance to an occupied Iraqi base near Jassan in 2003 (above), and the site in 2013 (below)

Muhammed said the town has been stable: “There are no strangers living among us in Jassan. Everyone is related or known, so troubles are solved by families.” I asked whether dividing Iraq into three states — Sunni, Shia, and Kurdish — would bring peace. He said no. “I’m from Zubaidi tribe, all over Iraq. We have seen other countries divided and see how much trouble they have.” I asked whether he met with any U.S. forces. “They came to ask some questions, like you do now. Didn’t achieve anything.”

I asked whether he remembered the night the council voted to close an illegal water pipe that irrigated a farm owned by Saddam’s wife Sajida. It was their first recorded vote as a governing body. He said, “Yes. Major Busch.” I wrote my name as if it were unknown to me, but I was pleased to hear it. The night of the vote, a child walked up to the front of the room and handed over a note from the Fedayeen Saddam that promised my death. I had driven off after that meeting sick with a high fever. The desert became a hallucinatory space as I struggled to stand, my night-vision goggles creating a claustrophobic depiction of the open land, the darkness shrinking the view, and my pyretic blood throbbing in my eyes. I don’t remember falling into my tent a few miles away or being worried about snipers, but I do remember walking out of the building with hundreds of men chanting, “Good Busch.” Through my illness it still felt like the only triumph of the war. I thought the new country would be all right. For one night I was sure of it.

Muhammed said Iraq was failing now because state officials are not qualified for their jobs. During the regime, officials had college degrees for their positions. He saw this problem all the way up the Iraqi government. “But Jassan is apart from Iraq.” He felt that the village has always governed itself, drifting in the country rather than anchored to it. “We had the first election in Iraq, and we have been working ever since. No one else in Iraq did this,” he said.

Saad Kareem Izbar, another original councilman, said, “We never agreed with any ruler. Iraq is always against its government (and all foreigners). There wasn’t much of that under Saddam, but he ruled with an iron fist. You can fix anything, but not the man himself. Saddam said that if he was going to turn over Iraq to anyone, he would turn it over as dirt.” I looked out at the desert and said, “And so he did.”

We visited Muhammed’s childhood home on the hill. The house had almost no decoration at all, high ceilings, bare walls of mud and straw painted white. It was cool and felt like an underground chamber. His family were all born here. Now he rents it to a relative and has built a new brick house. He showed me an original door made of slabs cut from a date-palm trunk. It looked ancient, worn, and dust-dried. He opened it with true pride, a museum artifact still at work in a dying town. It was the first time I had been inside a home in Jassan. As a Marine I always stayed outside.

We left the hill and went to meet the new council chairman, Abu Hassan, at a tiny café whose interior was painted a flat pink. We sat with five of the original councilmen on a ledge padded by single sheets of cardboard. I asked what had changed since Saddam. They seemed most upset about the awarding of government posts to Maliki’s friends and allies. “Before the new government, the old employees of the ministries worked very hard and serious, not watching our watches. Now they just wait for salary and holiday.”

I passed around pictures from the “military records,” photographs I had taken myself in 2003, and they were thrilled. They called out the names of people and handed them back and forth. A man smiled at one and said, “Major Busch.” The picture he held did not have me in it. I asked him to explain. “Only Major Busch could have taken this picture. He carried a camera and visited my house.” “Did he go inside for tea?” I asked. “No. He went inside no homes. He allowed no raids in Jassan.” “Did you ever invite him inside?” “No. Our women were there. Only we invited him for tea.” At this, a councilman told my story.

“Major Busch had tea with us on the hill and asked why we poured our tea into our saucers. We told him it cools it quicker. Busch asked why we didn’t just wait for it to cool off. We all laughed and said if we waited we would never form any agreements.” The councilmen all laughed again together. What they remembered so well of me and found so extraordinary, I did not remember at all. I would be told this story again from two other men in Jassan. There was something pleasant in hearing stories about myself, like being present at my own funeral. They did not recall the message declaring my imminent assassination. They recalled only that I was there. Drink your tea and all will be fine.

I asked how they felt about people moving off the hill. “The new houses are better, of course. Life on the hill was harder. But I miss the old way. We were all close. Everyone lived together. The doctor lived beside the herder and the farmer. Now we just pass sometimes.”

Abu Hassan took us up the slope again, into old Jassan. The curved passages through the town are all too narrow for cars, so supplies are carried from door-to-door by donkey. I could hear children playing behind the earthen walls.

The tour followed the same route as the one I had been given in 2003 and Hassan repeated the same anecdotes. He showed us the house that was bombed during the war with Iran — rebuilt by a local Iraqi army commander with his own money. “Two women were killed,” he said. I asked whether the soil was contaminated. “Only artillery and air bombs here. Not chemical attack. Soil is fine.” He estimated that 80,000 palm trees were destroyed by the Iraqi army during the war. So far they have planted only a few replacements.

Here in the center of the old village was the original meeting house, an empty room with quartered palm trunks as ceiling beams and woven reed mats to hold the clay roof. No one maintained it anymore, and a corner had opened as if hit by a bomb. Sunlight came in through the hole now, but it must have been completely dark when it was intact, everyone inside lit only by fire. It had fallen into use as a manger, the floor spongy with an uneven depth of sheep manure, a few handmade rugs sinking into the filth. An old man wandered up and spoke with reverence in the space, telling of when the British governor met with the village elders in the 1920s. “He had tea right here,” he said. “This is a historical site, and the government should preserve it.” They have asked, but no one cares. “Soon this will be gone,” he said. “All the stories will have no home.” It will just be an empty square on the hill, like the British cemetery in Kut.

The exterior wall around the settlement was giving way in places, revealing empty rooms and exposing the town’s mysterious interior, so long concealed. “Every year there are more like this,” Abu Hassan said. “If the roof is not maintained before the rains, in two years a house will fall.” An elder added his suspicion: “This is part of a plan to thin the blood of the village. These loans are chains to the government. Always we lived without debt on the hill. Now we live in brick houses . . . but we don’t own them. We leave the place of our fathers and accept a home that can be taken from us. What will our sons have? Not even memories.” But he has moved off the hill, too. “We used to watch the sun set on the land. Now we watch the TV.”

And then there I was again, in the middle of a sentence about the past, Major Busch drinking tea with the grandson of the man who drank tea here with the British governor in 1920 — neither of us remembered as enemies, but neither of us remembered for anything more than having been here once. It could have been centuries ago, the old men telling brief stories of our brief presence. We’ll all have to hope there were children in the room to hear them or we will finally, truly be gone.

We headed back down to the market. It was the feast of Ashura, and about three hundred people had assembled for qimah, a dish made from ground lamb, chickpeas, tomato sauce, and spices, which was served from large aluminum pots. We spoke with Jabir Surman Daoud, who was captured on May 6, 1982, during the war with Iran, and released nine years later in a prisoner exchange. He said life as a captive was good. He had a job at the post office before the war, when Jassan was peaceful. When he returned, the area was crowded with the Iraqi military. He felt like he was returning home to a prison. He resented being away but didn’t blame that on Iran. “We were forced to fight, like against America. We were not volunteers.” I asked what he dreamed of when he was young. “Saddam could see our dreams, so we did not have any.”

I spoke with Jaoudit Abdul Settar as he waited in line for food. Settar was two days into the six-day walk to Karbala from Kazania, his hometown. He had been a carpenter, but all furniture is imported now. “Kazania is also built on a hill. It’s doing the same as Jassan: loans, new houses, everyone leaving the hill. Saddam destroyed our town once before because he accused us of helping Iranian troops. Now we are destroying it.”

As we left, Khalil said, “Jassan is a dead town. Tourists bypass and they have no real product except some farming.” It was a cold assessment of a place that appeared to be well managed and progressing in a country that was largely broken. But he wasn’t wrong.

After three days in Jassan, we drove to the town of Badra, the last Iraqi settlement before the Iranian border. The old section of village was leveled during the war with Iran and is nothing but low earthen ruins now, a worn maze where rooms had been. Saddam had built some new concrete apartments and government offices there, but, like Jassan, brick houses are rising on the outskirts, making the pre-invasion buildings look dilapidated by comparison. We visited the border with the city manager, Jafar Abdul Jabar Muhammed, who had salt-and-pepper stubble and wore a tidy checked blazer. Like so many government managers, he was gracious with his time and guarded in his answers, but as we traveled with him he began to open up. “Our problem is water,” he said. “There is drought, and our farms take from the Badra River.” We crossed a bridge over the wide, dry bed. The river flows from Iran, but the Iranians built a dam and cut it off, he said. “I can’t imagine my childhood without the river. I tell kids the stories, but they see only stones.” The area had been known for its date palms, but we drove past dead orchards, hundreds of tall, bare trunks standing beside living groves that had been kept irrigated. It takes about eight years for a palm to begin producing date crops. It takes one bad year for it to die. It was not only the water, though. Some families have moved away for work in the cities, neglecting their plots of palms. “Before America came, everyone stayed.”

On the approach to the border checkpoint, we saw several lifeless miles of empty cargo trucks either returning to Iran or waiting to load Iranian exports. There were no trucks of Iraqi products. We also saw parking lots full of buses for Iranian passengers traveling to Karbala. The government in Kut has allocated billions of dinar to build a welcome center here to encourage more tourism from Iran. Nearby is the new Badra Oil Field, which is being drilled by the Russian energy company Gazprom Neft. It is a joint venture with oil companies from South Korea, Malaysia, and Turkey. The well is now producing 15,000 barrels a day. Half of the jobs are contracted to be local, which Jabar Muhammed believes will solve all of Badra’s unemployment problems. There were no American oil companies here, and he said Americans didn’t even bother to bid on the project. I was the first one he’d seen in six years. The border follows a rise in the land, and, like most boundaries that aren’t defined by a shore, it is an arbitrary division of uninhabited space. In 2003 we were told to keep our distance because the placement of the line was still contested, our maps only an estimation. Now it seemed like the end of nothing and the beginning of nothing else, Wasit Province a territory with customs stations on both sides, one for Iran and one for the other fragments of the former Iraqi state.

(“They’re trying to change the maps,” a merchant in Kut’s souk told me. “They are always moving the borders here, since Nebuchadnezzar. All these dead empires from outside. Why here? They’re drawing lines in water.”)

(“They’re trying to change the maps,” a merchant in Kut’s souk told me. “They are always moving the borders here, since Nebuchadnezzar. All these dead empires from outside. Why here? They’re drawing lines in water.”)

Now the borders we watched so carefully, a vigilance we inherited from Saddam Hussein himself, have almost dissolved. Sunni militants have captured Iraqi cities and declared the territory part of their caliphate. The government in Baghdad has called out for American military aid while cursing us, and we have begun bombing campaigns again. Two battalions of Iranian troops, known to have been employed in attacks on U.S. forces during the occupation, have been welcomed into Iraq.

On the route back to Kut we passed the site of the mass grave I saw in 2003. The dead were revolutionaries America had encouraged to rise against Saddam during our first invasion of Iraq. Our withdrawal had left the rebellion unsupported, its members identified and executed. After our invasion, families came to take the bodies for proper burial. They dug the bones and lifted them out of the pit; the arms were still bound with wire and the skulls still blindfolded with strips of cloth. For twelve years they had been in the soil here, unmarked, and now their empty graves were filling in like the trenches along the border.

My tactical maps were all lost when I went home. All I have left is an evasion chart I never used. On it is a tiny square representing the former Iraqi army base where my unit had been stationed. Years ago, I stood in the courtyard of a military training school here as Iraqi maps from the war with Iran blew all around me. Nothing but pulverized bricks and a few concrete bunkers were left now. The bunker entrances still had graffiti from Saddam’s army scratched into them along the stairs descending underground, the interior now used as a shelter for herds of sheep. It felt like an ancient tomb inside, the floor soft with dung and the dead carried off. In 2003 the footprints of Iraqi soldiers were still fresh in the dried mud.

Back in Kut we watched the news. Cloying coverage of Nelson Mandela’s death, riots beginning to push over police barricades in Ukraine, fighting in Syria. Nothing yet about Iraq. As we waited for a cab to Baghdad, there was a brief notice that Peter O’Toole had died, Lawrence of Arabia dead again as the Middle East began to redraw his map. I finally told Khalil that I was Major Busch. “Holy shit!” he said, extending a hand to shake as if I had performed a magic trick. His face was lit up for the first time in our eight days together. “They didn’t know you.”

We spent our occupation complimenting Iraq on its sovereignty, its bravery, never believing it. What was most surprising, seeing our total disappearance, was that 1.5 million Americans served in Iraq. We were 5 percent of the country’s population averaged over a decade; 4,486 of us died there; none of us are buried there.

I have now seen Jassan’s old walls falling, its children eternally standing there only in my photographs. Jassan will continue to exist, its name still on maps exactly where it was, but it will not be the place the elders remember. It will not resemble their stories of it. I am already unrecognizable to the people there, part of Jassan’s past life and not part of it at all. Why should I have expected us to be real to Iraq, to be lasting, when Iraq is starting over again every day without us?

We sought for years to define the Iraqi people, give their nation one cogent label that would allow us to administer a cure. But Iraq has every disease there is; its mind is deranged with too many voices, its organs corrupted, its limbs only long enough to tear at its own body. “It was religion that did this,” one man I met shortly after I arrived told me. “It is religion fighting. Iraqis aren’t themselves. They were an invention by the British. Me, I’m Sumerian.” I asked how he knew. “I just do.” When I asked whether he favored Iraq’s division, he said, “No. That won’t help. The three parts would be ruled by the outside countries, and they would fight.” Several men I met said they were proud to be Shia, but they didn’t think Iraq meant anything anymore. “It is just a place. Since Babylon it has just been a place.”

The Iraq I knew already seems to be underground, the new situation piling up on top of it, the people lamenting its burial but unwilling to dig. The land around Kut is filled with the unmarked graves of foreigners, the removal of the tombstones in the official graveyard just the natural urge of the desert to be blank. The mass grave we exhumed near Badra is filling in, the loose bones and clothing moved and buried again out of order, mud villages slowly reduced to mounds, images of Saddam destroyed, museums looted and the Americans gone, all the footsteps from all the patrols rubbed off by the wind.

On the way back to Baghdad our cab went 100 miles per hour and smelled of gasoline. The windshield had a crack, and my view of everything was split by a bright line. Unlike the village, where the past was being abandoned, Baghdad looked like a place preserving the war, its wreckage kept on display. How many times has Baghdad fallen? This was the land believed to have been the location of Eden, Adam and Eve expelled for taking the advice of a snake.

The main route to the airport was closed to allow Shia pilgrims to walk without the threat of car bombs, so we had to take the long way around to the south and then head west. As we passed a sign that said ramadi, fallujah, and abu ghraib, I was reminded that I was crossing an invisible line between religious sects and into a part of Iraq where most stories about Americans are grim. On the long road to the terminal, a single word appeared in polished silver letters raised on a curve of concrete: goodbye. It was in English, without translation into any other language. No one else is bid farewell from Baghdad. We probably paid to have the sign installed, wishing ourselves away.

Back home in the quiet snow of Michigan, I saw a one-line report about an explosion in the Karada district and wrote to check on Khalil. A few days later he wrote back:

Dear Sir,

Thank you for asking the explosion by booby-trapped car was near my apartment all the window glasses were flown up every were thanks god my both daughters were safe, my wife almost got killed by it, but she is safe.

Best regards,

Khalil

Baghdad is preparing for another invasion. ISIL is executing young Shia men from the surrendered Iraqi army, their bodies displayed in bloody ditches, mothers and fathers looking for their children in the grainy videos being posted by terrorists. I imagine families peering into those glowing frames, trying to know for certain that their son is dead. My father used to study the news reports during my deployments, scanning the troops walking behind journalists for men who might be me. The nameless announcements of casualties became his child every day until he had proof that it wasn’t. He was far from the war, but Iraq also seems a place far from itself now, its own ruins mostly distant, Iraqis in the east viewing Mosul and Ramadi as foreign places few have ever seen, the desert separating everything with sunlight. ISIL has gotten to within a few miles of the capital. They drive American military vehicles and they carry American weapons. Some now wear our uniforms. We have sent troops to guard our embassy and the Baghdad airport. The embassy is the last piece of ground we own, kept out of touch with Iraq in the International Zone, and the airport is the only way out. We are defending the silver sign that says goodbye.