The dog was my fault. I knew perfectly well that a Pekingese would be wrong in a household of ridgebacks and Irish setters. I also knew that one didn’t buy puppies from a pet shop. Our dogs came in as rogues — the runt of someone’s litter, or a stray, or a gun-shy hunter that refused to breed. But at thirteen, severely discontented with the dos and don’ts of life, I wanted to see just how far the determination to do the wrong thing might take me. And so I nagged.

Even after the heart was out of my petition, I kept it up. As the youngest child in a large establishment of family and servants, I seldom had my way with anything. Still I persisted. Meal after meal I harangued them. I just didn’t know how to stop.

But then one day, and to my alarm, my parents gave in. Enough! they said. They were sick of me! Sick of the sound of my voice. Okay! they said, the bloody puppy! Fine!

So there he was now — a nervous little creature that would scuttle under a chair whenever anyone, person or dog, approached him. He yapped and squealed and wet the carpet, and when someone reached down for him, he bit. After a while he bit even if you didn’t reach down for him, darting up to nip an ankle or a foot. And he was particularly fond of biting children.

“If one weren’t a bit squeamish,” my mother said, “one would simply tell one of the servants to drown it.” She was sitting across the couch from my father, well into her first glass of Scotch.

He ran a hand across his brow, which was to say he’d had a long day and this sort of thing was not what he wished to come home to.

“If anyone drowns him,” I shouted, “I’ll report you to the SPCA!” I was rolling around on the floor with the big dogs, not much caring what was decided, although I still felt obliged to keep up my side of things.

My father slammed down his glass. Reporting anyone for anything was not the way we did things. And it wasn’t funny. He was about to bellow something to this effect when Emma arrived in the doorway.

“Master,” she said, “I knock, but no one they hear me.”

“Yes, Emma?”

“The small dog, he can stay with me.” She closed her lips over her large front teeth and cupped her hands, one into the other, in formal supplication.

This was startling, not because she had overheard our conversation — news in that house, despite its big rooms and thick walls, seemed to carry, as if by magic, to wherever the servants happened to be — but because Africans generally did not like dogs, and for good reason. Just let an African walk past a house, and the dogs would be after him, roaring, snarling, leaping at the fence. Let him set foot inside the gate, and he’d need a stick or a whip to defend himself.

The improbable thing was that Emma had fallen in love with this puppy from the start. Perhaps for her, as for our other dogs, he wasn’t really a dog at all. Whenever the dogs saw him, they would rush up in a pack as if chasing a cat. And then she, who as part of the household was exempt from their terrorizing, would come bustling in, shooing them off, heaving herself onto her knees so that she could coax him out from under a chair with a few lines of “Sentimental Journey.”

Song was as natural to Emma as talking. More natural in a way. Out in the laundry, she sang the hymns she’d grown up with — “Rock of Ages,” “The Lord Is My Shepherd.” If I happened to walk past, she’d gesture madly for me to join in so that she could harmonize. She could harmonize with any hymn, any song, even those she didn’t know.

She had grown up in a Methodist mission station in Zululand, the daughter of a Methodist preacher. As a teenager, she’d been sent to the city, like other Zulu girls, to go into domestic service. How difficult this had been for her — how big a part homesickness played in the hymn singing out there — I never asked myself. I just sang along, teaching her some of the hymns we sang in prayers at my Christian school, and a song or two I’d learned in my afternoon Hebrew classes. Soon I’d hear her trying them out, adding ornaments here and there, turning minor to major to cheer things up a bit as she wielded the iron, serenading the puppy.

And the strange thing was that he never bit her. When he heard her voice, he’d push his flat little snout out from wherever he was hiding and then wriggle into the open, wagging, licking, trying to clamber into her lap. Soon he was trotting happily after her in the house like a small, mobile mop. If the other dogs became too much of a nuisance, she would scoop him up and put him into the pocket of her apron, singing to calm him down.

She had learned popular songs from the kitchen radio, which she would plug and unplug as she moved from room to room, dusting, tidying, making the beds. She listened not only to Your Hit Parade but also to the morning soap operas, in which my parents, who were actors, often played parts. If the story was becoming too tense to bear, she would come shyly, like now, at drinks time, when she knew, as did we all, that my parents were at their mellowest, to ask them whether this character or that was indeed going to die, or leave her husband, and was the baby going to be a girl or a boy, she herself was hoping for a boy?

But now here she was, standing solemnly before my parents, pleading formally for the puppy’s life. We had all seen her singing to him as she carried him about over the weeks. It was an eccentric situation, unprecedented for us, and everyone found it funny. Still, it had occurred to no one that she could be the solution to the problem.

My parents looked at each other as if to say, Why not? They asked her a few questions, pretended to consider. And then, nodding graciously, they pronounced her the new keeper of the dog. It was to sleep in her room in the servants’ quarters. And, yes, she could name him anything she wished.

As it turned out, she had the name ready: Hong Kong, because he looked Chinese, Honky for short. No one considered this odd. “Honky” was not a word in use in South Africa then, and is not now either — not as a racial slur or as anything else. Anyway, none of us had ever seen a Chinese person. Under apartheid, Chinese were categorized as colored; Japanese as honorary white (although none of us had seen a Japanese person either). We’d seen photographs and films and cartoons. And so Honky was Honky, and that was that.

It was only twenty years later, once I was living in America, that I found there was another meaning to the word. I was being asked by the bank, which I had phoned to set up an account, to choose an answer to a security question. I could choose one of various questions, all of them relating to childhood: A favorite pet? A best friend? The name of the street on which I’d lived? I chose favorite pet and, because he was the least favorite, thought I might find it easiest to remember Honky. “Honky,” I said.

There was a pause. “Could you repeat that?” said the operator.

“Honky,” I said again. “H-O-N-K-Y.” I was used to this. My accent seemed to make me particularly difficult to understand on the telephone.

“Hold, please,” she said.

I held. And held. Until, after about ten minutes, I hung up and, with some annoyance, phoned again.

This time, I was passed directly to a supervisor, someone of a different order of understanding. “All we need,” she said curtly, “is your mother’s maiden name and date of birth. Thank you,” she said, “the account is now active.”

Having a dog in her room made difficulties for Emma with the men in her life. When she adopted Honky, Reuben, the houseboy, a proud, dark Congolese man, who was her lover, ordered her to put him out of her room at night. But Honky was not negotiable, and there were loud rows in the servants’ quarters. After some weeks or a month of this, and quite suddenly, the authorities deported Reuben back to the Congo, and Emma became unsmiling and doleful, singing solemn Easter hymns as she moved through the days, Honky in her apron pocket. I couldn’t even tempt her with “Stormy Weather,” one of her favorites. “Ai, no, Bum,” she would say, “too much work to do.”

Ours was a family of nicknames. To Emma I was Bum, another word unrelated to its American meaning. I never asked why. To me she was Amazinyo Kanogwanga, Rabbit Teeth, or Empress Wu of the Feathered Dog. My first boyfriend, a plump, devoted, hapless boy, she named Pullman Bus, Pullman for short. “Bum,” she’d say, “Pullman at the gate.” And when, eventually, she took up with a new man herself, someone as cross and unpleasing as she was cheerful and pleasant, she called him Old Man, although he was no older than she was.

When I asked her to write out the words of “Nkosi Sikelel’ iAfrika,” a hymn she and I had sung many times together, she said she would ask Old Man to do it, he was educated and knew how to spell. But when she asked him, he just clicked his tongue. “Ai, suka!” he said. Old Man was political, she whispered to me. By which I took it that he was annoyed by the idea of a white girl presuming to learn a black hymn.

Emma herself, who had had to leave school after Standard Four, was a keen reader. Every night she read Napoleon’s Book of Fate to find out what lay ahead. She also read the Bible and the newspaper, and taught herself to read recipes and to calculate times and temperatures for when she had to take over as cook. But she was not political. Political in the Fifties and Sixties was a dangerous thing to be, and for Emma it held no romance at all.

Her romance lay in the songs she sang: “Sentimental Journey,” “Now Is the Hour,” “Tennessee Waltz.” There was also the holy romance of praise and supplication — “Jesu, Lover of My Soul,” “Oh God, Our Help in Ages Past.” She sang to console herself or to lift her heart, to rejoice if there was something to rejoice over, or just to keep herself and Honky company when there was no one around to join in.

In a household of mild eccentrics, she fitted in quite nicely. Every now and then, for instance, she was in the habit of hauling one of her enormous breasts out of her uniform and leaving it hanging there like a balloon. This she did with such pride and good humor that it seemed to me simply something she did, the way my father wrapped his head in a silk scarf every morning, like a pirate, to straighten out his curls. Anyway, it was often perishingly hot in our subtropical climate, and she was a large woman, who wore thick stockings for her varicose veins and wool slippers with pom-poms for her flat feet. So perhaps she was just cooling off.

Whatever the case, I’d laugh along and, when I was still a child and she supervising my bath, reach out for the baby powder and shower the breast with it to turn it white. “You naught!” she would say, happily brushing the powder off. And then on we’d go with my bath, she reminding me yet again to save up some urine to wash my face, it was good for the skin.

“Bum,” she wrote, once I had left home and was living in America, “Wu finish with Old Man. My mind is made up. I am too old to wait, so I have come to the conclusion that I walk to you in America if you do not send for me. Honky he give away. Time for me to leave.”

Honky given away? I wrote to my parents, remonstrating loudly. But my mother just wrote back to say that when they’d moved from the big house to a smaller maisonette, they could take only one dog with them, and that was, of course, Simba, the last of the ridgebacks. They’d found an elderly teacher, however, long retired, who was only too pleased to have Honky, although she’d changed his name to Fluff.

“Dearest Child,” Emma wrote, “surprise for you. Wu is got no teeth all gone. Please let me know about the life there in America. I am get old and I like to know everything. Who sing with you now? Who laugh?”

No one was the answer. I was married to a sour, humorless man, who happened also to be tone-deaf. “Oh, Amazinyo Kanogwanga,” I wrote back, “I’m coming home in July!”

She was waiting in the driveway as we drove in from the airport. There she stood without her teeth, her whole face sunken in, her body, too, it seemed. “Oh, Em-Bem!” I cried, “no more Amazinyo Kanogwanga!”

She laughed, all gums, and Nicholas, the new houseboy, laughed behind her, carrying in my suitcases. “Wu she get old, Bum,” she lisped. “Too late now for America. You must come home.”

The next time I came home, she was dying. When I went to see her at McCord Zulu Hospital, she looked up out of the skeleton that was left of her. “Bum,” she whispered, “please bring Napoleon Book of Fate. Please bring XXX mints.”

But when I came with the book and the mints the next day, her bed was stripped and empty. The patient in the next bed closed her eyes and turned her face to the wall.

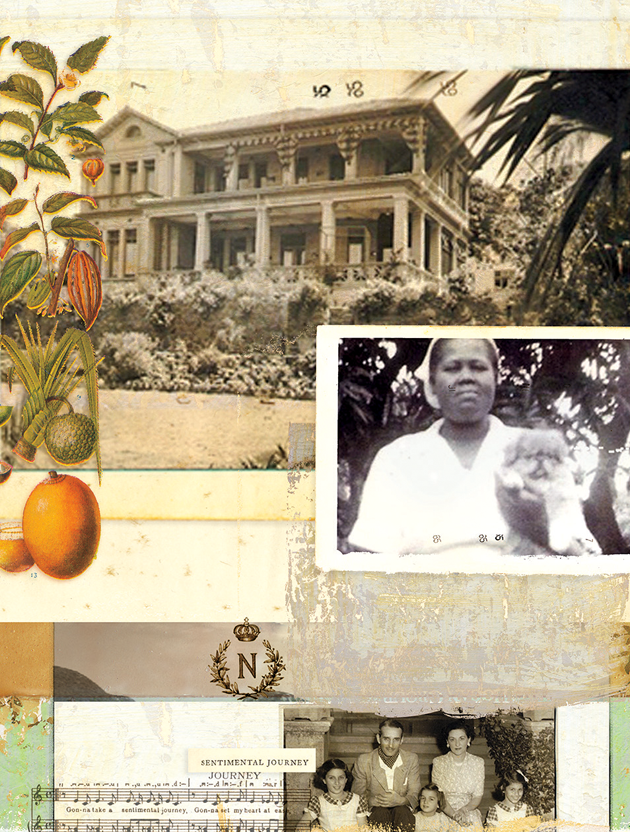

I stood where I was, holding the worn old book, as awkwardly as if I were being asked to believe a lie. A photograph was closed into it, keeping a place: Emma and Honky under the mango tree, I had taken it myself. She had composed herself for the camera, Honky under one arm, her lips closed solemnly over the front teeth.

Soon her family would be coming to claim what she had left behind, people I hardly knew. They’d knock at the kitchen door, asking for my father, wanting money for the funeral — a goat or a pig.

I tucked the photograph into my pocket and made my way out of the hospital. Nicholas would be making fried sole and chips for lunch today. When Emma began to feel ill, my mother had instructed her to teach him how to cook. But she had just turned her back so that he couldn’t see what she was doing, and my mother, who couldn’t cook herself, had had to intervene.

I stood out in the sunshine, breathing in the heat of the day. In a few weeks I’d be returning to America. For the rest of my life, I thought, I’d be arriving and returning like this, everything loosening and shifting over time, with less to leave behind me, another world to come home to again.