Even before Juliana Deguis Pierre became famous, or infamous, any Dominican who saw her would have guessed that she was of Haitian descent. Her dark skin, wide nose, and what is, in the Dominican Republic, called pelo malo — “bad hair” — immediately identify her as the child of Haitians, even though she was born in the Dominican Republic and has never been to Haiti.

Until September 2013, Deguis’s life followed a pattern common among children of immigrants. Like Latin Americans in the United States, Haitian immigrants in the D.R. do the menial jobs that most Dominican citizens try to avoid: construction, harvesting fruits and vegetables, cutting sugarcane, cleaning homes, and nannying children. About 7 percent of the people who live in the D.R. are immigrants, roughly the same proportion of first-generation Latin American immigrants living in the United States. Many Haitians crossed the border at the invitation of Dominican businesses or were smuggled in by Dominican traffickers. Deguis’s parents immigrated four decades ago, when a Dominican sugar company contracted them to work as cane cutters. The company never secured them working papers, but when Deguis was born her parents inscribed her in the civil registry and got her a Dominican birth certificate. They raised her in a company town called Los Jovillos, where she still lives today. Deguis has held several jobs, most recently caring for children and working as a maid in Santo Domingo, the capital, which lies two hours south of Los Jovillos, for 1,500 pesos (about $35) per week. In 2008, the family that employed her suggested that she register for the cédula, or I.D. card, that is necessary to work legally in the Dominican Republic. Deguis was twenty-four years old and pregnant with a son, and she would need the I.D. card to get him a birth certificate.

CESFRONT border-control guards watch for Haitians trying to cross illegally into the Dominican Republic. Photograph by Pierre Michel Jean.

At the Junta Central Electoral, the Dominican equivalent of a passport office and D.M.V., officials told Deguis that her birth certificate was invalid and that she was not eligible for an I.D. card. “How is it possible that my birth certificate is invalid if I was born here?” she asked. Until 2010, the Dominican constitution guaranteed jus soli, a right that grants citizenship to anyone born in the territory of a state, with the exception of those whose parents were “in transit,” a provision understood to cover diplomats and tourists in the country for fewer than ten days. But in the 1990s, the Junta Central Electoral began to refuse papers to Dominicans who, like Deguis, have Haitian names or faces. Without further explanation, the officials confiscated Deguis’s birth certificate.

Shocked, Deguis and several other plaintiffs sued the government, and her appeal proceeded all the way to the Constitutional Tribunal, the country’s highest court. There the case backfired badly. On September 23, 2013, the tribunal handed down ruling TC/0168/13, “the Sentence,” as it became known around the world. The tribunal revoked Deguis’s citizenship, declaring that her undocumented parents were “in transit” when she was born. More disastrous still, the Sentence applied to all Dominicans with undocumented foreign parents, most of whom, like Deguis, have no family in Haiti, speak little or no Creole, and are not eligible for Haitian citizenship. The decision was retroactive, affecting anyone born in 1929 or later. Two hundred ten thousand people were suddenly stateless.

“I’m a nobody in my own country,” Deguis said at the time. When I met her in Santo Domingo, last summer, she shook my hand with a feathery touch and spoke so softly that I had to lean in to hear. She told me that the Sentence had paralyzed her life, and the lives of the other denationalized people, who became known as los afectados. They could not legally work, marry, open a bank account, get a driver’s license, vote, or register for high school or university. “If you don’t have a document, an I.D. card, you can’t work anywhere,” Deguis said. Nor could she travel: in March 2014, the United States issued Deguis a special visa to visit Washington, D.C., to testify before the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights. Deguis showed me a photocopy of her visa, stamped by the Department of State. “My luggage was packed,” she said. She was stopped at the airport by Dominican authorities who claimed that she did not have the paperwork to legally depart the D.R. There was no guarantee, they said, that she would be allowed back into the country. Deguis returned home.

Guerline Laurent, twenty-five, and her husband have lived in Ranchadero, a Dominican town near the border

with Haiti, for six years. Photograph by Pierre Michel Jean.

As a result of her case — and the Sentence — Deguis is now notorious on the island. Dominican television covered her trip to the airport as breaking news. People stop her on the street to greet her and express support, or to tell her to “go back to your country” — by which they mean Haiti. Deguis’s parents worry that nationalists will try to harm her, and friends warn her to be careful, saying, “Everywhere you go, people are looking at you, on all of the channels they are talking about you.” United Nations officials call her the “rock star of statelessness.”

The Sentence alarmed many foreign politicians and public intellectuals. Michel Martelly, the Haitian president, denounced it as “civil genocide.” The United Nations protested the Sentence. The U.S. State Department voiced (noticeably weak) criticism in a daily briefing. Dominican-American writers Junot Díaz and Julia Alvarez, Haitian-American writer Edwidge Danticat, and American writer Mark Kurlansky sent an outraged letter to the New York Times: “One of the important lessons of the Holocaust is that the first step to genocide is to strip a people of their right to citizenship.” Critics of the Sentence seized on comparisons to Nazi Germany not only to show they were appalled but also because there are so few historical precedents for mass statelessness.

A CESFRONT video camera in the Dominican border city of Dajabón monitors the Río Masacre, which separates Haiti and the D.R. Photograph by Thomas Freteur.

The Sentence split Dominican public opinion. Some supported reconoci.do, a protest group that defends the rights of the suddenly stateless. Two of the eleven judges on the Constitutional Tribunal, Isabel Bonilla and Katia Jiménez, wrote harsh dissenting opinions, arguing that the ruling contravenes international law and “injures human dignity.” But many in the D.R. lashed out, saying that international criticism amounted to a violation of national sovereignty; the Dominican Republic could do whatever it liked with its Haitians and their children. A group of Dominican authors accused Díaz of being a “disrespectful and mediocre” writer, and a government official named José Santana called him a “fake and overrated pseudo-intellectual” who should “learn to speak better Spanish before coming to this country to talk nonsense.”

But it was the public protest of Mario Vargas Llosa, the Peruvian Nobel laureate, that cut deepest in the D.R., where the author had received every literary prize on offer and was considered something of an adopted son. (Also, in Latin America, where left politics are as indispensable to an intellectual as a beard is to a revolutionary, Vargas Llosa is a conservative exception.) In the Spanish newspaper El País, Vargas Llosa wrote that the Sentence

is a juridical aberration and seems to be directly inspired by Hitler’s famous laws of the Thirties handed down by German Nazi judges to strip German citizenship from Jews who had for many years (many centuries) been resident in that country and were a constitutive part of its society.

The only crime of the afectados, he wrote, was “belonging to a despised race.”

To protest Vargas Llosa’s equation of Dominicans with Nazis, a large crowd of nationalists gathered in Santiago, the country’s second-biggest city, where they stomped on a copy of The Feast of the Goat — his 2000 novel about the assassination of Dominican dictator Rafael Trujillo — doused it with gasoline from a plastic water bottle, and set it on fire. After the book burning, more than sixty community organizations signed a formal petition to request that the government name the author persona non grata in the Dominican Republic.

When two countries, one richer and the other poorer, share a border, it is a given that people from the poorer nation will pass over the border to seek a better job and a better life. Today the Dominican Republic’s economy is about eight times the size of Haiti’s, but until the turn of the twentieth century Haiti was richer than the D.R. During centuries of colonial rule, when the island of Hispaniola was divided into French and Spanish possessions, the Spanish side was the cattle-raising backwater, and people there had to cross the border to buy luxuries like perfume.

Haiti is the world’s only nation formed by a successful slave rebellion. It was the second republic in the Western Hemisphere, after the United States. In 1825, two decades after Haiti triumphed over France, its former colonizer surrounded the island with gunboats and extorted compensation from the new republic for the “property” lost in the revolution: slaves. France demanded 150 million gold francs, later reduced to 90 million. Haiti was forced to borrow from French banks to meet its payment deadlines, and it was 122 years before it was able to pay off both the ransom and loan interest. This is one reason why mention of Haiti now is so often followed by the phrase “the poorest country in the Western Hemisphere.” In 2003, President Jean-Bertrand Aristide’s government asked France to return the money, which he claimed amounted to $21.7 billion. France refused.

The young republic of Haiti ruled the Dominican Republic, then called Santo Domingo, from 1822 until the two sides separated in 1844. These dates have been seared into Dominican consciousness as an occupation, the most humiliating episode of their history. Dominican Independence Day is celebrated not on the day the country gained freedom from Spain but on the date of independence from Haiti. Spain even briefly recolonized the D.R. in 1861, at the invitation of a Dominican leader looking to salvage the economy and his own authority, who used threats from Haiti as a pretext for the action, according to historian Anne Eller. Still, into the early twentieth century, the line between Haiti and the Dominican Republic remained porous, and along the border people from both countries farmed side by side and intermarried.

The young republic of Haiti ruled the Dominican Republic, then called Santo Domingo, from 1822 until the two sides separated in 1844. These dates have been seared into Dominican consciousness as an occupation, the most humiliating episode of their history. Dominican Independence Day is celebrated not on the day the country gained freedom from Spain but on the date of independence from Haiti. Spain even briefly recolonized the D.R. in 1861, at the invitation of a Dominican leader looking to salvage the economy and his own authority, who used threats from Haiti as a pretext for the action, according to historian Anne Eller. Still, into the early twentieth century, the line between Haiti and the Dominican Republic remained porous, and along the border people from both countries farmed side by side and intermarried.

This peaceful coexistence was shattered in 1937, when Rafael Trujillo, as part of his project of whitening the Dominican population, ordered the murder of between 7,000 and 15,000 Haitians who were living on the Dominican side of the border. Trujillo himself had a Haitian grandmother, and wore pancake makeup in the Caribbean heat to lighten his complexion. He was famous for never sweating. An artist I met in Santo Domingo told me that the dictator “looked out the window” and realized that if he didn’t want his country to be considered black, he would have to invent a new racial category. Dominicans were henceforth to be indios, a categorization that appeared on government-issued I.D. cards until 2011.

The 1937 massacre is known in the D.R. simply as el corte, “the cutting.” To differentiate Haitians and Dominicans, Trujillo’s men forced residents with dark skin to pronounce the word for parsley, perejil. If they could not roll the r like a Spanish speaker, they were executed. The army used machetes to make it look as though nationalist farmers had turned on their neighbors spontaneously, without government orders or assistance. The border city of Dajabón saw so many killings that it was said the nearby Río Masacre — which divides the two countries and was named for a colonial skirmish — ran red.

The United States, which had recently withdrawn from a military occupation of the D.R. that lasted from 1916 to 1924, expressed only mild dismay. Trujillo was trained on a base by U.S. Marines and rose to power through the ranks of the Dominican National Guard. According to historian Eric Roorda, a Dominican emissary to the United States explained the 1937 massacre as something necessary to “preserve our racial superiority.”

A year later, in an effort to improve his international image, Trujillo announced a plan to accept hundreds of thousands of Jewish refugees from Europe, and he built the Sosua Jewish Refugee Settlement on the northern coast of the island. A promotional video showed pale immigrants sunning themselves on the tropical beach.

In accordance with his Good Neighbor policy, Franklin D. Roosevelt presided over negotiations between Haiti and the D.R., after which Trujillo promised a $750,000 indemnity to Haiti but sidestepped responsibility for the killings on the border. In the end, Trujillo paid only $250,000, plus several bribes to Haitian officials, and only a few hundred Jews were ever settled in the Dominican Republic. After the issue was resolved to his satisfaction, Trujillo nominated Roosevelt for the Nobel Peace Prize.

A few days after I arrived in the Dominican Republic, I attended a convention on migration law at the Autonomous University of Santo Domingo, the country’s most prestigious university, that was hosted by the National Association of Independent Lawyers. I was curious to hear the keynote speech, by Juan Miguel Castillo Pantaleón, a former judge and an outspoken supporter of the Sentence. When I arrived at nine that morning, I noticed that someone had sprayed graffiti on the wall surrounding the campus: different color of skin, same color of blood. In the pristine white lobby of the library, men in khaki suits and women in tight dresses and stilettos filed into a lecture hall.

Pantaleón, a stocky man with gray hair combed back in a George Washington flip, began with remarks on Dominican sovereignty. He called the Sentence an “extraordinary synthesis” that had been smeared with “distortions and disinformation of the most repugnant kind.” Juliana Deguis, he argued, might make a “presumptuous” claim on nationality, “but she isn’t Dominican.” The audience interrupted him to applaud.

Santiago’s Hato Mayor neighborhood, whose sizable Haitian population has been subject to harassment. Photograph by Thomas Freteur.

Pantaleón turned to Haiti, a “failed state” suffering a demographic explosion. “Culturally, and this also happens in Africa, the man doesn’t use controls on his sexuality or contraception.” Pantaleón told the audience that Haiti has the highest birthrate in the Western Hemisphere. (This is incorrect.) Referring to Deguis, he said, “the point is that this woman, Haitian, here is not going to get rid of her ancestral custom by crossing the border or getting I.D.’s. You don’t change identity like you change underwear.

“We must suppose that these habits and customs are encouraged here because of a health system that has considerably reduced infant mortality. What operated as a natural and unfortunate population control in Haiti doesn’t exist here. Of seven children, here all of them will live. What will happen in fifteen years?” he asked. “I don’t think I’m a fascist to talk about this, because it is reality.” In fifteen years, he declared, “the Dominican Republic will confront the greatest of its challenges, that of possibly being a minority in our own country.”

Pantaleón is not by any means the most radical anti-Haitian in the D.R. He is not a member of the “night guard,” which patrols the capital. He does not burn out Haitian homes or murder immigrants, as frequently happens outside the capital, where poor Haitians and Dominicans live cheek by jowl. The agricultural and border regions in particular experience long stretches of peace punctuated by violence: one-off attacks on Haitians as they pass through forested parts of the border on foot, retaliation against large groups of Haitians when rumor spreads that a Haitian has killed or robbed a Dominican.

When anti-Haitian feeling flares in the D.R., it can reach the level of superstition, or paranoia. Some believe a disastrous earthquake hit Haiti in 2010 because Haitians, unlike Dominicans, are not “a people of God.” Others posted on Facebook that it was a pity the earthquake had not killed all Haitians. A number of people told me about the so-called Plan de las Potencias (“Plan of the Powers”), a plot by the United Nations, United States, and European Union to fold Haiti into the Dominican Republic, thereby absolving the great powers of responsibility for what right-wing nationalists call the failed state next door. The plan is top secret, naturally, but Bill Clinton supposedly let it slip at a convention at Punta Cana. One professor told me that belief in the Plan of the Powers, as ludicrous as it may sound, is not uncommon among her colleagues at the Autonomous University.

Although Dominicans have a mix of European, African, and indigenous roots, their chosen heritage, their usable history, is European. Santo Domingo is home to the first cathedral of the Americas, the first hospital, and even the first tavern (built in 1505), now a “European Brasserie” where I tried an excellent dish of shrimp and chorizo called Don Quixote’s skillet. Many women in the restaurant had hair dyed brassy blond and a spectral skin tone, white and yellow at once. Whitening “skin fade” cream starts at under two dollars in pharmacies. (Sammy Sosa, the Dominican baseball player, is an example of startling skin bleaching surpassed only by Michael Jackson.)

During the colonial era in Latin America, a lexicon developed to express the exact proportions of indigenous, black, and white blood in each subject of the king. Those terms gave way to an infinity of local slang to describe race: “coffee with milk,” “cinnamon,” “wheat-colored.” In Mexico I’m not only a gringa but a güera or even a rubia, a blonde. Never mind my curly dark hair, or that my Irish grandmother politely referred to my Jewish mother as “pigmented.” “Blonde” refers to my light eyes, my foreignness, the fact that I’m whiter than the local white people. In Latin America you see more clearly what is also true in the United States: race doesn’t exist without a referent. Dominicans are not black people in denial. In their country, “black” means Haitian, or a child of Haitians. To Dominicans, the supposed distinctions are clear: Dominicans are European. Haitians are African. Dominicans are Christian. Haitians practice voodoo.

Madam Lebrun, a cane and charcoal seller, has lived in the D.R. for more than twenty years. Though two of her children were born in Santiago, they have never been issued identity papers, and her own passport is no longer valid. Photograph by Thomas Freteur.

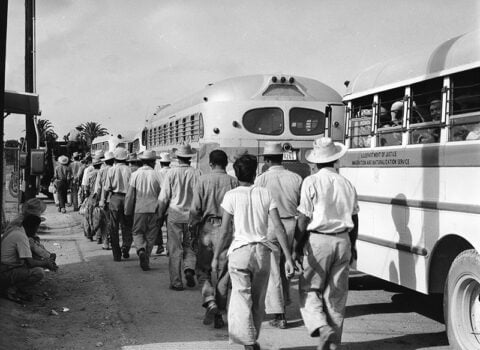

It can be a shock for Dominicans to move to the United States and find themselves on the other side of the color line. “Until I came to New York, I didn’t know I was black,” wrote the Dominican poet Chiqui Vicioso. Some of the sharpest criticism of the Sentence, and of Dominican treatment of Haitians more generally, has come from the 850,000 or so Dominicans living in the United States. Many see their situation in an often hostile and racist country as parallel to that of Haitians in the D.R. It is fitting, then, that the Haiti–D.R. border looks like a small-scale version of the U.S. border with Mexico. Indeed, the D.R. is the United States’ pupil in immigration policy. With U.S. financial assistance and training, the D.R. created a border-control guard, CESFRONT, for the first time in 2006. A 2008 U.S. Embassy cable released by Wikileaks describes CESFRONT’s “regular round-ups of suspected Haitians” in border areas, “based on ‘profiles’ usually nabbing darker-skinned individuals or persons who ‘looked’ Haitian e.g. an elderly woman carrying fruit basket on head.” Last year, CESFRONT inaugurated a new shooting range, donated by the U.S. Embassy; more than one Dominican pointed out to me that it was rich for a girl from the United States to start sniffing around the D.R. for problems with racism and immigration. (Other Caribbean countries, like the Bahamas, have also started to crack down on Haitian immigrants. The New York Times reported that in 2013, one official in Turks and Caicos vowed to “hunt down and capture Haitians illegally in the country, promising to make their lives ‘unbearable.’ ”)

Last June, a Dominican congressman proposed building a wall along the border with Haiti. The congressman, Vinicito Castillo, is the son of Vincho Castillo, a powerful politician who was a crony of Trujillo’s. After Trujillo’s assassination, in 1961, Vincho switched his allegiance to Joaquín Balaguer, who served three terms as president. Balaguer used to complain that Haitians were “darkening” the country and, in his famous book La Isla al Revés (1983), warned that Haitians were trying to invade the D.R. using a secret weapon, the ability to “multiply with a rapidity that is almost comparable to that of a vegetable species.” In 1994, Balaguer torpedoed the presidential candidacy of his opponent, José Francisco Peña Gómez, by spreading rumors that Peña Gómez, who had dark skin and African features, was actually Haitian. (Balaguer, whom Ronald Reagan called the “father of Dominican democracy,” died in 2002 and was eulogized as a national hero.) Vinicito Castillo was sworn in to Congress last summer with the Nazi salute used during Trujillo’s dictatorship; he defended his border wall against critics by citing the example of the United States.

Ten days after arriving in the Dominican Republic, I took a bus to a beachfront town near the border with Haiti to meet Jhonny Rivas, a Haitian man accused of killing a witch. The Montecristi prison is up on a scrubby hill, overlooking a town of the same name. Wednesdays and Sundays are visiting days, when the wives and mothers of prisoners bring home-cooked meals. While I waited to pass inspection, I watched guards pop open Tupperware containers and drag knives through rice, beans, and salad, looking for drugs. I was led to a side room where two naked lightbulbs protruded from opposite walls. There was a fat woman in a black folding chair, and a mirror with a gilded frame lying at an angle on the floor. Another woman was squatting over the mirror, her pants and underwear pulled down, to show that nothing was hidden in her vagina. The fat woman indicated that it was my turn.

Jhonny Rivas at his home in Ranchadero, after his release from the Montecristi prison. Photograph by Thomas Freteur.

In the prison, human bodies filled the hallway so thickly that it was hard to pass through; the building was meant for 100 and houses 469. I knocked on a door covered with a white sheet, and Rivas pulled it open. He is a thin man with finely drawn features, and was dressed in a guayabera shirt and pressed trousers. When he stood to greet me, his head grazed the ceiling. The cell was fourteen by six feet. The narrow bed left only a small strip of empty floor. A Virgin Mary was drawn in marker over the head of the bed and surrounded by heavily inked red and blue stars. It was hot and airless. Rivas told me that he stayed in his cell as much as possible because he was afraid of mixing with the other prisoners, many of whom were in for drug trafficking. In a journal, in tiny script, he had been keeping track of his days in prison — 336 in total.

Rivas emigrated from Haiti to the D.R. in the late Nineties. He worked on a banana farm, where he was disturbed by the exploitation of his fellow immigrants. He volunteered for, then was hired by, an NGO called Solidaridad Fronteriza, which advocates for Haitian rights in the border region. In 2004, Rivas led a strike demanding that employers pay undocumented workers benefits. Two years later, he was elected president of an immigrant-workers’ association linked to Solidaridad Fronteriza. Local Dominican landowners and businessmen, whom Rivas calls the “little group,” started to eye him askance. Farmworkers warned him that the little group was out to get him, and he received death threats. In 2008, Amnesty International released a notice on his behalf: “Urgent Action — Fear for safety: Jhonny Rivas and his family.” Rivas avoided walking alone at night.

In 2013, his union won a lawsuit against a group of banana-plantation owners, who had to pay more than $67,000 in fines and compensation for not providing benefits to Haitian workers. Afterward, Rivas recalled, “When they saw me, it was like the meeting of a cat and a dog.” He was sometimes followed as he went about his work.

One of Rivas’s projects was to distribute thousands of identification badges. Members of the workers’ association came up with the idea years before the Sentence, when it was already clear that a lack of documentation was making Haitians and their children vulnerable to harassment. Rivas heard stories of employers bribing immigration officials to deport Haitian workers the day before they were to be paid, and of soldiers regularly extorting undocumented immigrants by threatening deportation. He traveled around the border region collecting information — how long Haitians had lived in the D.R., how many children they had, where they worked — before printing personalized badges with the workers’ association logo. The I.D. badges carried no legal weight, but people who wore them reported less harassment from authorities. Rivas became locally known and respected. He married a Haitian immigrant named Roseline; they had three children and settled in a two-story white house, the grandest structure in a dirt-road town called Ranchadero, near the border.

In May 2013, Rivas’s seven-month-old son swallowed a large insect called a hiede vivo and died. Almost everyone in town was sure the child was killed by sorcery. A month later, Adelina Charlot, a woman who ran a small business casting spells for her neighbors, was found dead, stabbed in her home in Ranchadero. On July 11, two police officers entered Rivas’s house without a warrant and arrested him for allegedly sending another man, Joel Charlet, to have the woman killed. Rivas protested that he’d never met Charlet and that the arrest was retribution for his work with immigrants. Many Haitians and some Dominicans in the area practice voodoo, but Rivas told me that he doesn’t believe in witchcraft. He’s an evangelical Christian and saw his infant son’s death as a trial sent by God.

Charlet, who is Haitian, allegedly implicated Rivas in a confession before a public prosecutor. Charlet speaks no Spanish, the prosecutor speaks no Creole, and there was no interpreter present for his testimony. Later, in an official hearing with a translator, Charlet testified that he didn’t know Rivas and that he’d never spoken to him. Yet Rivas remained in jail. One of Rivas’s Haitian colleagues at Solidaridad Fronteriza indicated to me that Rivas may not have operated with the maximum caution in his work, that perhaps he was too outspoken in his fight for immigrant rights: “Jhonny was always confronting authorities. And he always won. Now it is their moment.”

Rivas told me that after he was arrested, the public prosecutor said he could not be released on bail pending trial because he was a flight risk — he might escape to Haiti. Rivas has a house, a wife, and two children in the D.R., but the prosecutor argued before a judge that it was impossible to know whether Roseline was his real wife or whether her children were really his: none of them had Dominican I.D. cards. The judge declined to let Rivas out on bail.

Rivas took out a sheaf of pictures from his Bible. He showed me a photo of his twelve-year-old son, Jacques, and ten-year-old daughter, Jessica. They stood side by side, skinny and dressed all in white, arms stiff by their sides, staring up at the camera. Guards did not allow them to visit Rivas at first, because they lacked proper documentation: visitors to the prison must leave their I.D. card or passport at the front gate, where they are given a slip of laminated yellow paper with a number, like a coat check.

Rivas was allowed to leave prison only to attend hearings, which involved substitutions of judges and the mysterious disappearance of parts of the transcript, including Charlet’s declaration that he did not know Rivas. The public prosecutor in charge of the case was assisted by two private lawyers, supposedly paid for by the family of the victim but rumored to be contracted by the little group.

Rivas told me without bitterness, “Justice here is money.” A local car dealer had claimed that for the equivalent of $6,000 Rivas could walk free.

When I asked Rivas about his next hearing, which was set for the following day, he was hopeful. “I have many enemies, but I trust in my God. I don’t think he wants this bitter cup for me.”

Rivas’s predicament was a more extreme version of the abuses that Haitians and their children had recounted to him for years. Back in Santo Domingo I had wondered: What was the point of denationalizing the children of immigrants if deporting people on a large scale would wipe out the cheap labor on which so many Dominican industries and families relied? Anti-Haitian sentiment alone didn’t cover it. Rivas’s case suggested an answer — labor control. Anyone in the United States who pays a Central American or Caribbean housecleaner under the table knows that immigration status accounts for her affordable rate. Making the afectados stateless would keep them in the same weak position as their immigrant parents — permanently. Rivas had meddled by trying to improve their lot.

The next morning, I took a motorcycle taxi to Montecristi’s tribunal, a two-level, peach-colored building that was spacious and airy inside. Rivas sat in the front row, handcuffed to an enormous man in a fitted white baseball cap: Charlet, the alleged killer. They were surrounded by armed guards with automatic rifles. Five Haitian men and one woman filed in to register as witnesses. The woman was young and pretty, in jeans, a striped polo shirt, and a matching white headband with blue flowers. She was Rivas’s wife, Roseline.

After the witnesses were announced and Rivas’s lawyer gave a brief statement, the hearing was adjourned: the trial could not proceed because some witnesses for the prosecution were missing and — crucially — no official court interpreter was available. Another complication was that Rivas’s passport had been confiscated at the last hearing, and now the authorities said they could not find it. (Roseline became agitated. “They have it,” she said. “Why don’t they give it to us?”) The next hearing was set for several weeks later, and Rivas returned to prison still handcuffed to Charlet. The whole proceeding lasted twenty-three minutes.

Shortly after the Constitutional Tribunal handed down the Sentence, President Danilo Medina met with a group of afectados at the presidential palace. I was told he shed tears listening to their stories. International pressure on Medina to do something for the afectados was intense, but he could not simply reverse the Sentence. Instead, in November 2013, he issued a presidential decree launching a regularization plan for immigrants without papers, the vast majority of whom are Haitian. Anyone who immigrated to the Dominican Republic before October 2011 could apply for regular migratory status and, eventually, citizenship.

The following year, the path to citizenship was made open, if less clear, for the afectados. Under a new law, passed in May 2014, afectados fell into two groups. Those who had been inscribed in the civil registry and issued birth certificates before the Sentence, like Deguis, could be “accredited” as Dominican citizens, which would give them the right to I.D. cards and passports. This group includes about 24,000 people. Those afectados, however, who were born in the Dominican Republic before 2007 but did not have a birth certificate were required to embark on a complicated, uncertain application for naturalization. First they had to prove their birthplace by providing one of four acceptable documents, such as a signed statement from a midwife or witnesses, then they had to apply through the regularization plan. The majority of afectados thus found themselves in a similar position to Haitians who crossed the border more than four years ago, never mind that they had once counted as citizens. The law requires that beginning this June, all immigrants and afectados who have not completed the application, or whose applications have been denied, will be deported.

An optimist might hope that what began as a Dominican court’s massive experiment in denationalization might end in the Dominican government’s massive experiment in naturalization. But difficulties immediately became clear. Even the lucky group of 24,000 afectados with birth certificates had to obtain their I.D. cards from the Junta Central Electoral, the same body that had been denying such papers for years. The protest group reconoci.do has documented at least 150 instances in which afectados in this group were illegally denied papers. The day that I met Deguis, she had been turned down and told she needed to apply at a different office. Deguis finally got her I.D. card on August 1 of last year. For the first time in six years, she could work legally. She received a passport a few weeks later, but it is still not clear whether she will be able to register her four children as citizens.

Obstacles for the nearly 186,000 afectados without birth certificates are even more formidable. Any applicant for naturalization, whether afectado or Haitian, must present documents proving their length of stay in the D.R. and “ties” to Dominican society. Among the possibilities are a deed to a house, a letter from a schoolteacher, a note from a boss, or a notarized memo of good conduct from seven Dominican neighbors. Unaccompanied minors also need death certificates for their parents. Every Haitian document requires a notarized translation into Spanish. All of the correct papers must be presented at one of thirty-one designated offices, none of which are in bateyes, the isolated company towns in which many Haitians live. No funds are provided to transport applicants. Most of the applicants are poor, and many are illiterate. The plan, one NGO director wrote me, was a “Kafka–Orwellian jamboree.”

Gustavo Toribio, the director of Solidaridad Fronteriza, the NGO that employs Rivas, was recognizable right away; several people had described him to me as a big man, “black as a Haitian.” A few days after Rivas’s hearing, early on a Sunday morning, Toribio was at the NGO’s headquarters in the border city of Dajabón, dressed in head-to-toe khaki linen with two signet rings and a gold watch. He gathered piles of pamphlets in Creole and Spanish that detailed the steps required to qualify for the regularization plan and loaded them into his car. Solidaridad has more than 6,000 Haitian workers organized in the northern border region, and Toribio was off to a meeting of regional leaders. The idea was to initiate them into the intricacies of the plan so that they could teach other people in their communities how to apply.

The meeting was in Ranchadero, the town near Montecristi where Rivas lived with his family before his arrest. Toribio was pleased at the turnout, which included many children wearing party dresses and bright barrettes. I sat next to a ten-year-old girl who was particularly well turned out in a purple and black dress and a white headband with blue flowers. I asked her what she thought of the plan. “It will work,” she said with confidence. She explained that her parents are Haitian and that she was born in the D.R. She and her brother, a younger boy with a more serious expression, were among the afectados. Her parents, she said, were going to take care of the process for her.

An old woman sitting on my other side told me that she had crossed the border in 1993 to find work. Her Spanish was shaky, so she borrowed my pen to write the year on her palm. She was convinced that she would now become a Dominican citizen: she was documented to the hilt. Her six children, all born in the D.R., had birth certificates. She had a Haitian birth certificate and a Haitian passport. She had a membership card from the union. The only thing that worried her was that these documents were under different names. (Toribio later told me that even without clerical errors — which the government has said will invalidate any document — changing names is common Haitian practice. “Jhonny Rivas” is an assumed name, too: Rivas used to be Jackson Lorrain.) The woman would have to legally amend the documents so that the names matched, but she didn’t know where to do so or how much it might cost.

Toribio taped up a big piece of brown paper on the wall and wrote regularization plan. The meeting was an “emergency,” he said, otherwise he’d be at home with his family for Sunday lunch. Toribio asked for a show of hands: How many of the forty-six people in attendance, not including children, had heard of the plan and knew how to apply? Six men raised their hands. The audience was made up of union leaders, the well informed, the literate. If they didn’t know how to enroll in the plan, how many would?

Toribio explained that the first phase of the regularization plan was already over. November 2013 to May 2014 was the informational stage, “And as we can see they didn’t do that well.” He wrote the deadline for enrollment in the plan on the brown paper: february 28, 2015. He wrote the last date for submitting all of the paperwork: may 31, 2015. “In June 2015,” he said, “all those who aren’t regularized will be deported to Haiti. Even if you have been living here for a hundred years.” There was murmuring. “Are you worried?” Toribio asked. “Good.”

Toribio fielded almost two hours of anxious questions. After the meeting was over, everyone I spoke to said they were missing at least one piece of required documentation. Most were missing several. They said that the process seemed complicated, but everyone agreed that they would become citizens. “It has to work,” an old man told me.

The girl in the flowered dress was flitting among the adults, teasing her brother. Only when someone called out her name — “Jessica!” — did I realize that she was Rivas’s daughter. She was wearing the headband Roseline had worn to the hearing.

I told Jessica I’d met her father.

“But my father is in prison,” she said. I told her I met him there. She called over her brother, Jacques. They wanted to talk about Rivas. With pride, the kids counted off the languages their father speaks — Creole, Spanish, English, and a bit of Portuguese. “He was a schoolteacher in Haiti,” Jacques said. Jessica said her father helped her with homework via text message. I remembered with a sinking feeling that Rivas had said he had not heard of the regularization plan. He didn’t get newspapers in prison, and anyway, he told me, “I’m thinking only of getting free.”

When I returned to the United States, I continued to receive updates from a friend of Rivas’s who attended his court proceedings. Every month or two there was a hearing, and every hearing generated new delays: Rivas failed to appear because authorities “forgot” the date or because the armed guards were busy breaking up a strike and couldn’t accompany him out of prison.

In January, the trial finally got under way. Charlet had confessed to sole responsibility for the murder, but the public prosecutor still requested sentences of thirty years each for Rivas and Charlet. A police detective testified that in cases of murder by machete, his men knew to investigate Haitians because “Haitians like to kill with a machete.”

The public prosecutor made a poor showing on the final day, confusing the names of people and witnesses. At one point he called Adelina Charlot, the murdered woman, Angelina Jolie. On February 13, I received an email saying that the trial was over. Charlet was sentenced to twenty years in prison. Rivas was acquitted for lack of evidence of his involvement, and his immediate release was ordered. He had been a prisoner for almost two years.

But Rivas’s ordeal ended just days after violence in the D.R. again made international headlines. A Haitian shoe shiner named Henry Claude Jean was lynched, strung up from a tree in a public park in Santiago with his hands and feet tied, one day after a group of Dominicans publicly burned the Haitian flag. Police maintain that the lynching was not a hate crime, but by all accounts race relations in the D.R. are at their most tense since the Sentence.

One week later, an afectado named Wilson Sentimo was eating breakfast with some friends at a food stand when three members of the Dominican military pulled up next to them in a truck. Sentimo did not have his birth certificate, so the soldiers deported him across the border. It was his first time setting foot in Haiti.

These are not isolated incidents. In February, about 10,000 people marched in Haiti to protest the violence against Haitians in the D.R. Because of political instability in Haiti — the parliament in Port-au-Prince was dissolved in January and the president was ruling by decree — the flood of people at the border was even larger than usual. The Dominican government “sealed” the border with Operation Shield, which CESFRONT, the border-control guard, claimed was blocking 500 Haitians per day from entering the D.R.

It doesn’t look like the vaunted regularization plan has done much to help those already in the country, either. Only 8,755 of the 186,000 afectados lacking documentation managed to register by the February deadline. Amnesty International warned that thousands of Haitians and afectados risk deportation because the government refused to extend the deadline. According to the Dominican newspaper Listín Diario, the minister of the interior, José Ramón Fadul, said that NGOs were to blame because they “haven’t helped the foreigners resolve their problems, on the contrary have only dedicated themselves to criticizing us.” Fadul accused Amnesty International of being run by Mexican interests who hoped to redirect tourism away from the D.R. to the Riviera Maya. At the time this article went to press, more than 150,000 people had attempted to begin the naturalization process — with no guarantee of approval — but that’s only one fifth of the estimated 700,000 Haitians in the D.R. I spoke with Washington González, deputy minister of the interior, and noted that after June 2015, once the deadline for the plan had passed, his government would have the phone numbers and addresses of all those who had registered for the program and were rejected or who did not complete their paperwork on time. Wouldn’t that make it easy to deport people en masse? González said, “We are not going to have” — he paused — “a hunt, so to speak. A persecution. But if someone is in conflict with the law, as in all countries it is possible to deport him.”

Dajabón is divided from the Haitian city of Ouanaminthe by a bridge that spans the trickle of the Río Masacre. In 1937, Dajabón was the site of the largest number of killings of Haitians, but there is no memorial or museum of any kind, unless you count the Hotel Masacre in the middle of town, which is probably named after the river. (Its sign reads your second home.) The city’s major attraction is the binational market of Dajabón, where twice a week thousands of Haitians sell goods at bargain prices. The market used to be informal, but it so choked the streets that, several years ago, a structure was built next to the bridge to house it. CESFRONT opens the bridge at seven-thirty on Monday and Friday mornings to allow vendors into the designated market area. Haitians come from as far as 200 miles to sell, Dominicans from as far as 180 miles to buy at cut-rate prices. There are clothes, electronics, shoes, furniture, beauty products, rice, and dried-out fish with vacant holes for eyes.

CESFRONT guards dress in tan camouflage, with fez-style camo hats and black knee-high boots laced up over their pants. When I visited the border toward the end of my time in the D.R., I watched them check the papers of incoming Haitians. A group of men behind a chain-link fence had been denied entrance. When a guard pushed an old woman back, a boy in an orange polo saw his opportunity and made a run for it. Even though this checkpoint is heavily guarded, many Haitians cross here because they are in greater danger elsewhere. Solidaridad Fronteriza gets calls from farmers in other places along the border complaining that they smell decomposing flesh in their vegetable gardens.

Crossing into the Dominican Republic for the market is supposed to be free, but the guards often take advantage of Haitians’ ignorance or desperation and charge people anyway. I saw one crumpling paper notes in his fist. This racket extends all the way down what is called la línea, a bus route from Dajabón to the central city of Santiago, the destination for many migrants. Extortion is so common that prices are fixed. A Dajabón–Santiago bus ride can cost 3,000 pesos, about $70, for an undocumented Haitian, factoring in bribes. The same trip cost me 200 pesos, or less than $5. A few decades ago a posting in the border region was punishment for a Dominican. Now it’s a prize. After six months, Toribio told me, the guards get posted elsewhere, to give someone else a turn at shaking down the Haitians.

I had left my passport at my hotel after being warned that the market was a good place to get pickpocketed. To my surprise, a guard told me I didn’t need it if I wanted to cross into Haiti “just to look.” It was midmorning, but hundreds of vendors were still streaming over the bridge into the D.R. Women passed with twenty-four-pound bags of garlic or crates of fresh eggs stacked on their heads. Several pickup trucks carried merchandise or the infirm, but the one lane was mostly filled with people on foot. I was the only person headed away from the D.R. I stopped halfway across the bridge, stared for a while at the Haitian side — at the invisible boundary so starkly drawn in the imagination of Hispaniola — and then turned around and walked back, as if it were nothing.