One frigid afternoon in January 2013, a man approached three brothers playing in a field in Kudiya, a hamlet in the northern Indian state of Uttar Pradesh. He had some paying work for them, he said, a loading job, if they were interested.

The Gupta brothers — Amrit Lal, Nakshed, and Akhilesh — recognized the man as Bhola Khan. Khan was in his twenties, and lived with his family in the Muslim quarter of the village. He worked at a local kiln, transporting freshly baked bricks in a horse cart.

A child laborer carries a stack of bricks at a brick kiln in Bhaktapur, Nepal, March 28, 2005 © Nicky Loh/Reuters

Amrit Lal, the oldest boy, was immediately agreeable. At fifteen, he didn’t need to be told that the family could use the money. Their father, Jagram, was working on a construction site in Lucknow, the state capital, eighty miles away. Their mother, Jagtapa, toiled in a neighbor’s paddy fields. An older sister was still unmarried; a younger sister was only six. The children were enrolled in the local government-run school, where a single classroom housed dozens of students. Everyone was of a different age and level, but they were all made to spend hours reciting the Hindi alphabet by rote. Amrit Lal felt that such an education was a waste of time. It would be better to work and put food on the table.

Akhilesh, who was ten, hung back. He helped his mother weed the slice of farmland that they had managed to keep out of the hands of creditors, but he was too young, he knew, for a real job. He was used to being petted and spoiled. His mother affectionately called him “little brother.”

Perhaps Bhola saw the indecision on Akhilesh’s face, because he quickly sweetened the offer. “I’ll give you a mobile,” he promised.

The boys had envied friends who flaunted their parents’ cell phones. Available for a few hundred rupees from a nearby bazaar, the gadgets were referred to admiringly as “China mobiles” for their country of origin. “I became greedy,” Akhilesh admitted later.

The brothers gathered four friends, who also took Bhola up on his offer. The seven children told no one where they were going and set off as they were. Akhilesh’s pants were ripped; his flimsy cotton sweater was no match for the cold, which in that part of northern India could plummet to seven degrees Celsius. Nakshed, who was thirteen, had just twenty rupees (thirty-seven cents) in his pocket — not even enough for a bus ride back.

On the road, Amrit Lal borrowed Bhola’s phone to call his mother. She scolded him for leaving and demanded that the boys return. But it was too late; Sajid Khan, Bhola’s boss, who had joined them en route, wouldn’t let them. Along the way Sajid had picked up another six boys, and he diverted the children’s attention by treating them to hot samosas, a fried potato snack that some of the boys had previously only heard about.

Sajid employed such tactics throughout the nearly 400-mile journey, which took the group out of India and into Nepal. In the border town of Nepalgunj, he fed the boys dinner at his own house and let them watch cartoons. Early the next morning, he herded them onto a bus headed toward Bhaktapur, a town on the outskirts of Kathmandu, where around sixty kilns produce bricks that are sold across Nepal and even to China for the construction of houses, luxury hotels, and corporate offices. But this number accounts only for the legally registered kilns. Other operations, like the one to which the children were taken — fifteen miles outside Bhaktapur — are buried in dense forests high in the mountains. Here, owners go about their business almost entirely unhindered by the police or labor inspectors who sometimes visit the more accessible kilns.

After two days of travel, the children were put to work stacking bricks. They begged to be taken home or at least allowed to call their parents, but Sajid ignored their pleas. He made them groom and feed the half-dozen horses used to transport the raw bricks to the furnace. Like the horses, the children were beaten with whips. These beatings so terrified them, Akhilesh said, that rather than attempt to escape, the boys “worked as fast as the animals.”

In October 2014, the Hindustan Times ran a small story about the children. When I visited Kudiya, last July, I learned that the reporter had neither interviewed the family nor seen where they lived. The Guptas were considered bit players in the story of their own lives. Such marginalization isn’t unusual in this region, where the literacy rate is only 34 percent, half that of the rest of Uttar Pradesh. Home to 204 million people, the state is more than five times as populous as California. Decades of misgovernance have given it a reputation as the most lawless part of the country. In 2014, it recorded India’s highest number of crimes against women: more than 38,000, an increase of 17 percent over the previous year. These are merely the crimes that the police documented; the actual number was, presumably, many times higher. In the spring of 2014, two teenage girls who belonged to a low caste were found hanging from a mango tree in a neighbor’s orchard — raped and killed, their family alleges, by higher-caste men. The case made international headlines, but remains unresolved.

Child laborers from India and Nepal load bricks onto their heads at a factory in Lalitpur, Nepal, February 10, 2014 © Narendra Shrestha/EPA/Newscom

Corruption in social-welfare schemes is widespread. The growth of half of the children under the age of five is stunted. Last year, a prolonged drought reduced some families in Uttar Pradesh to eating animal fodder. The state’s poverty is replicated to different degrees in other parts of India. The country boasts the world’s fastest-growing major economy, yet nearly 60 percent of people earn around $3.10 a day. Faced with the prospect of hunger, parents put children to work. Children cook and serve food in roadside restaurants. They haul bricks on construction sites. They dart among cars at red lights, selling pirated books. Behind the walls of factories, little boys weave carpets and little girls spin cotton. The idea that a child can do an adult’s job is as widely accepted in India as the opposite is believed in the United States: that childhood is a time for play, not toil.

Some children are abducted and forced to work, said Bhuwan Ribhu, of Bachpan Bachao Andolan (B.B.A.), a group that advocates for children’s rights. (The founder won a Nobel Prize in 2014.) But 75 percent of working children, he estimates, work with their parents’ permission, if not their full understanding of the conditions. Contractors promise high salaries or an education in exchange for labor, a maneuver that Ribhu calls “abduction by deception and enticement.” The parents’ acquiescence doesn’t make the men any less liable. What it means is that such parents do not see their children as victims of trafficking.

Ribhu told me that in January of this year, the B.B.A. had rescued twenty children in Delhi — nine from a bag factory, the rest from private homes where they were working as domestic help. All of them had been sent to work by their families. It was only after one boss stopped allowing the children to call home, to prevent them from complaining, that the parents approached the B.B.A. When deals go bad, parents complain. Otherwise, they don’t.

Something similar had happened with the Gupta children. Amrit Lal confided to me that he, at least, had known he was going to Nepal to work in a brick kiln. Bhola had told him so. The teenager knew that he would be required to work for at least ten days, and that he would be paid only after the work was completed. He went willingly.

India’s law against child labor, which was introduced in 1986, prohibits children under the age of fourteen from working in eighty-three occupations that the government deems hazardous, such as in mines and slaughterhouses. (Those between the ages of fourteen and eighteen may work in any occupation.) Another piece of legislation, against human trafficking, is also meant to protect children. In 2013, in the aftermath of a gang rape on a bus in Delhi, the scope of the law was widened, and trafficking of a minor was made punishable by imprisonment of a minimum of ten years. Where more than one minor was involved, the prison term could stretch to life. Most important, the ordinance clearly stated that the consent of the victim was immaterial to the “determination of the offense.”

In other words, it doesn’t matter that Amrit Lal initially agreed to go with Bhola. The laborer broke the law by knowingly putting children under fourteen to work in a hazardous job, and broke the law again by refusing to let them leave when they asked.

While the human-trafficking law has been strengthened, the movement against child labor is under threat. An amendment proposed in 2012 sought to prohibit children under fourteen from working in any occupation, not merely hazardous ones, but it has yet to pass. In May 2015, a new provision was introduced, allegedly with an eye toward boosting the economy, that allows children under the age of fourteen to participate in family-owned enterprises. Considering the number and variety of businesses in India that are run by families, the potential for abuse is huge. The new version of the amendment, which is still under review, will also cut the number of occupations categorized as hazardous from eighty-three to three. Working in a brick kiln will no longer be on that list.

In Nepal, the legal situation is similar. Children under the age of sixteen aren’t allowed to take hazardous jobs, and children under the age of fourteen aren’t allowed to work at all. And yet Bhola and Sajid had little trouble bringing seven minors into the country and employing them. The problem isn’t the laws, the activists I met in Nepal told me, it is the absence of any will to implement them.

Children have long been trafficked from Nepal into India; it’s only recently that Indian children have been taken into Nepal. Human traffickers now routinely transport children from Nepalgunj to Bahraich. They are taken wherever there is demand. At the checkpoints, no identification is required for citizens of either country to pass through. “Traffickers are now aware of the huge numbers of poor children in India,” Ribhu says.

On the Indian side, the police station is located in the dusty town of Rupaidiha. The station stands between an outpost for members of the Sashastra Seema Bal, the Indian armed force that guards the border, and a small customs-and-immigration booth. From the gate of the police station, Nepal is only a few feet ahead. Last July, when I asked him about the situation, Anil Kumar Yadav, the officer in charge, talked as though human trafficking were primarily the outcome of poor parenting. “They’ll give their child to anyone,” he grumbled.

Bindu Kunwar, an information officer with Nepal’s Child Welfare Committee, said that when the children don’t make a fuss, it’s difficult to know that they’re being trafficked. The children go voluntarily, she said. Their life is so hard that some of them go just for the meals they are fed along the way. Secure in the knowledge that their charges will be docile, traffickers amble across the border on foot.

In November 2014, Kunwar led a raid on six hotels in Nepalgunj. Sixteen Indian children were rescued; the youngest was six years old. Kunwar tracked down their parents, who lived in Bahraich, and discovered that they’d agreed to send their children to Nepal. In exchange, they received 3,000 rupees ($56). This sum, which was supposed to be an advance on a full year’s salary for each child, was less than 50 percent of what the hotels paid an adult for a single month. Not only were the children being made to work, they were also being underpaid.

When Kunwar asked the parents why they’d sent away their sons and daughters, they pleaded poverty. The traffickers offered money, they said, and promised to feed and clothe the children. Kunwar also asked the hotel owners about their rationale. One said that children work harder for less money and don’t steal. Whatever you give them to eat, they eat quietly and go to sleep. Children, in other words, are the cheapest and most easily manipulated form of labor. Even the poorest adults are more likely to stand up to exploitation. But a child, the hotelier explained, makes no demands.

If people were forced to hire adults exclusively, however, families would be less poor — and children, as a consequence, less likely to be pressured to work. “Children are poor because their parents don’t have jobs,” Ribhu said. “But their parents don’t have jobs because the jobs are going to children.”

Jagtapa doesn’t remember getting a call from her sons. She told me that when she returned home from work that chilly January evening to find three of her five children gone, she assumed that they were at a relative’s house — even though, she admitted, they had never before left without informing her. It’s likely that Jagtapa started worrying only after the children were no longer in touch.

Ten days passed before she called her husband, in Lucknow. The next day, Jagram was on a bus home. Jagram is in his fifties, but like his wife, who is around the same age, he appears many years older. Yet where she is stooped and looks worn-out, he stands tall. He has thick, shiny hair, and all his teeth. He refused to believe that anything bad had happened. “Children roam around from here to there all the time,” he told himself.

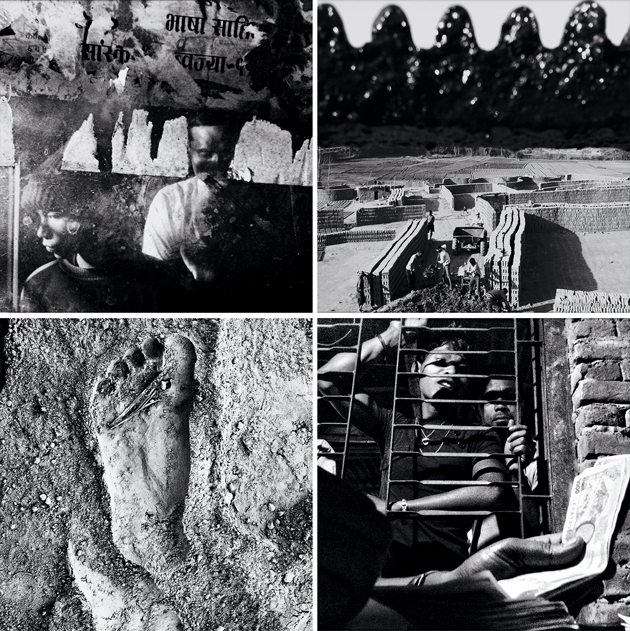

Clockwise from top left: Migrant workers watch management at a kiln in the Kathmandu Valley, in Nepal; workers load claylike earth into wheelbarrows and a small dump truck for transportation; workers wait to receive their cumulative pay at the end of the season; the footprint of a child laborer. All photographs © Brian Sokol

In Kudiya, he went from house to house, seeking information about his sons. The parents of the other missing children had made inquiries, he heard, but they hadn’t learned much. One of them mentioned that the boys were last seen talking to Bhola, so Jagram walked over to the Muslim quarter, on the other side of the village, to talk to Bhola’s wife, Reshma.

The Khans’ brick house had just one room, where Reshma spent all day with her children. Like many of the families in the area, the Khans had no electricity or running water. Matters had taken a turn for the worse six months before, after Bhola borrowed money from his boss and then failed to pay it back. The debt had made it hard for him to secure another job.

But one day, while stopping by a kiln in town, Bhola found himself in the company of a wealthy fellow Muslim named Sajid Khan. Tall and fair-skinned, with a black mustache, Sajid was recruiting people to go with him to Nepal to work at a kiln he owned there. He offered Bhola a job driving a horse cart and promised to pay him 4,000 rupees a month ($60), more than Bhola earned in India. He encouraged Bhola to hire a few employees on his behalf. It was a good deal, Reshma told me, and the couple was excited by this change of luck.

However, soon after Bhola left the country, villagers started visiting, demanding to know where Bhola had taken their children. Reshma was flummoxed. Why would her husband take anyone’s children? Reshma, who was illiterate, didn’t know where in Nepal he was, she said. When Bhola wanted to get in touch with her, he called a shop in the village and the owner sent someone to fetch her.

By the time Jagram arrived at Reshma’s doorstep, she’d had enough of what she saw as undue harassment. “If Bhola made a mistake, kill him,” she cried, shutting the door on Jagram’s face. “It’s nothing to do with me.”

Finding no answers in the village, Jagram expanded his search. He did not consider going to the authorities. People warned him that the police would accuse him of having intentionally sold his sons.

When someone enters an Indian police station to report a missing person, a detailed statement, necessary to open an investigation, is made out on his or her behalf. Rajit Ram, the station officer of Sonwa police station, under whose jurisdiction Kudiya falls, said that the police search for the missing person and solicit information from the public. They put up posters in high-density places such as railway stations and bus stops and upload the person’s photograph to the website of the National Crime Records Bureau, a government database. The photos may also appear on Doordarshan, the public-broadcast TV station.

Or that’s how it’s supposed to go. In reality, when someone poor and powerless like Jagram approaches the police with a complaint, he is dismissed. “He has no chance for justice,” asserted Jitendra Chaturvedi, the chief executive of Dehat, a nonprofit in Bahraich that runs a hotline for missing children. Chaturvedi attributes this reaction to the familiar Indian fusion of corruption and helplessness. The Sonwa station operates with a staff of twenty-four, and old equipment. The officers are expected to oversee more than 100,000 villagers. When, inevitably, they run out of cash — and sometimes even before — they ask the very people who have come for help to help them. “They would have known that Jagram had no money,” Chaturvedi told me.

When I asked Ram whether he was aware that children were being trafficked out of the district, he first said yes. Then he appeared to change his mind. “It’s very peaceful,” he insisted. “Children roam around freely.”

“The problem with the police,” Chaturvedi later said, “is that they don’t accept there’s a problem.” If they were to accept it, they would have to work to fix it.

Such apathy is hardly unique to Bahraich. In 2013, the same year that the Gupta children were abducted, nearly 80,000 children were reported missing in India. Of these, the B.B.A.’s Ribhu claims, the police investigated only around 28,000 cases. Three years later, thousands are still missing; Ribhu believes that they are likely working as bonded labor.

Under such circumstances, it’s understandable that Jagram decided against approaching the police. Instead, he talked to people in the nearby paddy fields, the jackfruit orchards, and, especially, the brick kilns.

The kiln owners are wealthy men with a vast network of contacts. Every year they hire dozens of people, including children. It is backbreaking labor, but the jobs are coveted because they last the entire fallow season, making it possible for rural, subsistence-farming Indians to work all year long.

The jobs are varied, and people with no experience are easily employed. Children as young as five break coal with their hands. Older ones mold clay into bricks. The men transport these bricks on horse carts to the base of the chimney, where the furnace is located. From a distance, the large, concrete furnace looks benign, but it is intensely hot. Fueled by logs and coal, it produces dense smoke that pours out of the chimney and unfurls across the sky in ashy trails.

Firing the furnace, laying down the raw bricks, and retrieving the finished bricks are dangerous jobs, and the men who do them earn between 10,000 and 15,000 rupees a month ($188–$282), a substantial amount in rural India. Others are paid by the number of bricks they make or carry.

If a kiln owner can’t accommodate everyone who wants work, he sends applicants to friends’ kilns in other villages or even neighboring states through his labor contractor, or thekedaar. Everyone works with the thekedaars, Jagram knew. “So when children go, the kiln owners know where.”

He was right. At a kiln just a few minutes’ walk from the village, a man named Afzal beckoned him over. He’d heard Jagram was looking for his children, he said, and he had information.

When he later analyzed Afzal’s offer, Jagram said that the man had taken pity on him. But Afzal wasn’t being entirely altruistic. In exchange for the information he had, he wanted 5,000 rupees ($94). This didn’t anger Jagram. “I would have given him ten thousand rupees to know where my children were,” he told me.

An energized Jagram raced back to the village to borrow the money. The next day, Afzal revealed that the children were no longer in India. They had been taken to Kathmandu to work. Jagram broke down. He didn’t know where Nepal was.

“Will I get my children back?” he asked helplessly.

“Yes,” Afzal nodded, “but you’ll have to be resourceful.” He told Jagram that he would introduce him to a man who knew where the children were. The man worked there himself.

Afzal then gave Jagram an extraordinary piece of advice. “Don’t say you want your children back,” he said. “Say that you want a job.”

Meanwhile, for the Gupta children and their friends, life in Bhaktapur had grown nightmarish. The kiln was located at a high altitude, and in January the mountains were covered in ice. Trapped in the midst of thick forests, the seven boys felt terrified and helpless.

Early on, Amrit Lal plotted to run away, but Bhola overheard him and told Sajid, who thrashed the teenager with a stick. The beating convinced the boys that they would be killed if they were caught escaping. Akhilesh believed that Sajid would hurl him down from the very top of the mountain. Even if they did run away, where would they go? They were in a foreign country. “We were small,” Akhilesh reminded me. “What could we do?”

On the day the boys arrived, Sajid made them build a makeshift house for themselves with bricks. It was by then clear to all the children that neither money nor mobiles were forthcoming: they had been brought to work as slaves.

Every morning thereafter the boys were woken when it was still dark outside. They weren’t fed breakfast. There was no water to drink. If they were thirsty, they chipped ice from a frozen stream and melted it in a bucket. This was such a physical hardship for the smaller children that they never managed to gather enough water to bathe with. In any case, there was no soap.

Apart from Sajid and Bhola, the only other adult working in the kiln, the children said, was Sajid’s brother, Munna. The three men loaded the furnace with uncooked bricks. The boys washed the finished bricks and stored them. This went on all day. At night, Bhola cooked them boiled lentils and rice. The adults ate meat.

One day, Akhilesh recalled, labor inspectors arrived. Sajid and the other men rounded up the seven boys and hurried them into the forest, where they were separated into small groups and hidden. “Move and we’ll kill you,” the men told the children. They stayed hidden the entire day.

Closer to town, where the legally registered kilns operate, labor inspectors and police are a regular sight. Mahendra Khaimali, a Nepali who owns the Shri Saraswati brick kiln in Bhaktapur, told me that police visited his kiln at least once a year.

Khaimali admitted that he hired children — around ten the previous season, out of some three hundred new employees. According to him, there are children working in every kiln in Bhaktapur. He didn’t ask labor contractors specifically for children, he claimed, and paid them the same wage as adults. But when a contractor showed up with a boy, he didn’t turn him away.

“If one of my thekedaars brings fifty people, of which four are children, and I refuse the four, he’ll refuse me all the others,” he said. The contractor exerts this pressure because he has already paid out money to the children’s families; he doesn’t want to suffer a financial loss. The relationship between a kiln owner and a labor contractor is based on mutual trust and need, but the kiln owner, because he depends on the migrant labor the contractor provides, has less power in the exchange.

The contractors earn a commission for every person they bring, and an additional cut of between 12 and 15 percent of each worker’s monthly salary. If a contractor delivers twenty people to a brick kiln, Bindu Kunwar said, he earns the equivalent of a year’s salary: “He can eat, drink, and relax for the rest of the year.”

Khaimali is in his early forties, and wears a collared shirt, cotton pants, and trendy sneakers to work. He is a father, and said that he is uncomfortable employing children. “I find it strange,” he told me. “But my finding it strange won’t solve the problem.” He can choose a different contractor, but that contractor, too, he believes, will bring children. Khaimali thought it was likely that the police noticed the practice but looked the other way because there isn’t a system in place for addressing it. Environmental violations, such as burning plastic, are easier to investigate and prosecute than labor infractions.

Kunwar seemed to agree. Labor inspectors don’t have the authority to rescue trafficked children, she told me. They must organize a team that involves government agencies and child-rescue officers, and bringing together just one such team, given the bureaucracy involved, sometimes takes up to six months. After a raid, the rescued children may be returned home, but the employers and traffickers often get away.

After Kunwar rescued the sixteen children from the Nepali border, she didn’t have the hotel owners arrested. Instead, she made them sign a document promising that they would never employ children again. Kunwar calls this free pass the Nepali government’s “humane” approach. It is based on the idea that people make mistakes and should be given a second chance. It’s not right, she admitted, but it is done.

The men who brought the children to the hotels were never arrested. But even if they had been, it’s unlikely that they would have done prison time. Trials often drag on for so many years that victims lose interest and refuse to testify. Or, having been threatened or bought off by traffickers’ families, they grow hostile. In 2014, the Nepali courts convicted only 203 traffickers.

Khaimali is a member of the Brick Entrepreneurs Association, a group of local kiln owners. In 2014, the government opened a school nearby. When asked if the children who came to work were told to attend, Khaimali sighed and said he wanted to tell me a story. “Last year, I grabbed a boy and took him to school. It’s five hundred meters away. He said, ‘I haven’t eaten anything, how will I study?’ ”

For the second time that week, Jagram borrowed money. He took 15,000 rupees from the village head, bringing his debt to 20,000 rupees ($376). Then he cycled over to Small Bazaar, where he was introduced to Afzal’s contact. As he’d been advised, he played the role of a grateful father. He praised the men who’d taken his children and begged a job for himself.

The man seemed to believe the story, and agreed to take Jagram to Nepal. When Jagram shared the good news with the villagers, two family members of the other missing boys volunteered to go with him. Before they left, Afzal said that he would be joining the group after all. In return, he expected to receive free labor from them whenever he needed it. As Jagram learned later, Afzal was Sajid’s brother-in-law. One member of the Khan family saved money by kidnapping the Gupta children; another made money by revealing their whereabouts.

The four men boarded a bus from Bahraich toward the border. They crossed over in a horse cart, and, once in Nepal, hitched a ride on a truck.

Later that night, after a cold, hours-long drive, Jagram and one of the other men from home walked into the brick kiln. Jagram’s youngest son was sitting outside, trembling with fever. For a small infraction, Sajid’s brother had smashed a brick across Akhilesh’s ear and the wound had gotten infected.

Jagram ran toward his son and engulfed him in his arms. “Don’t cry,” he said. “I’m here.” The child, he recalled, was “almost dead.”

The other children emerged from their huts. Some started crying, some screamed with joy. When Sajid came forward, Jagram made no mention of the abduction. He simply reminded the trafficker that the Hindu festival of Holi would soon be upon them, and said that he wanted to take his children home to celebrate. Sajid shrugged off the request, and the matter was left unresolved. Jagram and the other men ate dinner with the boys. At dawn, Jagram recalled, “We were getting ready to leave when the boss came running up to me.”

“Chutiya!” Sajid shouted. “Cunt! Where do you think you’re going?”

“I’m taking my children home,” Jagram said.

“I’ll throw you in with the bricks,” Sajid retorted.

Sajid offered to pay Jagram for the children, but Jagram refused. He didn’t want money, he said. He wanted his boys. Sajid then told Jagram that he would have to give him another group of children in exchange for the ones he wanted back. Finally, Sajid produced a stick and started thrashing Jagram.

Jagram had every reason to take Sajid’s threats seriously: the man had kidnapped his children, brought them to a foreign country, and was keeping them enslaved. It seemed to him that Sajid would go to any lengths to get what he wanted. So Jagram staggered away, followed by his companions. The children were in tears. Akhilesh was inconsolable. “Keep my salary, but let me go,” he wept. “I want to go home with my father.” Sajid responded by beating the boy.

The men walked as fast as they could. Arriving in Bhaktapur, they boarded a morning bus back to Nepalgunj. It was time to approach the police. But when Jagram went to the Sonwa station, he told me, the officer said that he couldn’t help because the children were in Nepal. (When I visited, the police denied having a record of Jagram’s visit. This doesn’t mean he didn’t go; most likely, no one took him seriously enough to file a complaint on his behalf.)

So that was that, Jagram told himself. He had gone to the police, he had gone to Nepal. The situation was hopeless. Jagram had given his children his phone number and some money, which he hoped they would use to buy food and medicine. Soon after, Amrit Lal called, and implored his father to come back for them. “We’ll die,” he pleaded. “If I return,” Jagram replied, “they’ll kill me.”

Sajid had been forcing the children to drink moonshine. Anyone who refused was beaten. The drinking was supposed to make the children pliable, but it also fueled their hunger. They began spending the money their father had given them on boiled rice and tea from the shop nearby. They called the woman who ran the shop didi, or sister. One day, after Akhilesh had received yet another beating, the woman urged him to run away. Otherwise, she warned, he wouldn’t live long.

Bhola, too, turned into an ally. The children didn’t know why, but they could guess: perhaps, just as Bhola had tricked them, Sajid had tricked Bhola. They had not been given mobile phones; it was likely that he hadn’t been paid the large salary that Sajid had promised him.

Bhola could have run off alone. But to his credit, he appeared determined to take the children with him. The question was how. Amrit Lal suggested that Jagram might be willing to meet them at the bus stop in Bhaktapur, fifteen miles down the mountain. Borrowing Bhola’s mobile, he surreptitiously called his father to find out.

Jagram was terrified of returning to Bhaktapur, but he was equally terrified of losing his children. His son gave him an ultimatum: Help us, or we’ll throw ourselves off the mountain.

Once again, Jagram had to raise money. This time, he sold his most precious possession — his land. When he accepted 122,000 rupees ($2,300) from the wealthy neighbor who bought the land from him, he asked to be given the opportunity to buy it back.

Arriving in Bhaktapur for the second time in three months, Jagram and the other men waited at the bus stop. It was three in the morning. The small town was silent. They waited for a call from Bhola announcing the children’s successful escape from the brick kiln. Just as Jagram’s phone rang, the children barreled down the street. They had descended the mountain in a burst of sheer adrenaline. Somewhere in the dark, stray dogs barked the alarm.

The plan had been to take a bus from Bhaktapur to Nepalgunj. But there were no buses running at that time of the night. Scared by the dogs, and sure that it was only a matter of time before Sajid arrived in his car, the entire group — seven children and five adults — started to run.

According to Jagram, they ran for hours. At some point, they believed that they’d entered Maoist territory. To save themselves from the rebels, they decided to hide until daylight. This way, they could also be sure that they were heading toward India rather than in the opposite direction. They slept in a sand heap. When the sun rose, they hitched a ride on a truck carrying cauliflowers. In Kathmandu, they caught a bus to Nepalgunj. The children slept fitfully on the journey, afraid that Sajid and his henchmen were behind them, racing to catch up.

But Sajid wasn’t behind the bus. He was waiting for the bus. When they arrived at the Nepalgunj depot, the disembarking group saw Sajid and several of his friends, armed with bamboo sticks. Jagram later guessed that the bus driver was an informant of Sajid’s.

There were hundreds of people at the station. But Jagram said that the group were so scared that no one dared protest.

“We’ll chop you up into pieces,” Sajid’s men yelled, swinging their lathis.

Two of the adults and three of the children managed to flee. Everyone else was marched out of the bus depot and down a narrow alley to Sajid’s house — the same place the children had been taken when they had first crossed into Nepal three months ago. But this time, instead of getting a hot meal and a TV show, they were locked in a room.

Around two in the afternoon, Jagram asked for permission to leave to smoke a bidi. Pacing up and down, he happened to see Sajid’s wife working in the kitchen, and he had an idea.

“Madam,” he called politely. He approached Mrs. Khan with folded hands. In a traditional Hindu gesture of respect, he bent down to touch her feet. He was a devoted father, he told her. His children had called him to come for them, he said, so he did. He didn’t know they hadn’t told the boss. He claimed that he was embarrassed to discover that his sons were trying to shirk their jobs.

When the men returned, Sajid’s wife argued eloquently on Jagram’s behalf. She pointed out that their captive had fields to tend and other children to feed. Keep the boys and the other men, she counseled. But let this one go.

Finally, Sajid agreed. He even gave Jagram money to go home. “Never do this again,” he said sternly.

Upstairs, Amrit Lal tried to console his younger brothers. “Don’t cry,” he whispered. “Papa will come for us.”

Outside, Jagram hailed a cycle rickshaw. As soon as the rickshaw heaved into motion, he collapsed into tears.

“Why is he crying?” a man standing on the side of the road asked the driver. He was a “big man,” Jagram recalled, by which he meant that the stranger appeared to be educated and well-off. The Good Samaritan paid the rickshaw driver and bought Jagram a cup of tea. “I’m in trouble,” Jagram confided, and started his story from the beginning.

Jagram’s luck had finally turned. The man who had taken pity on him knew a prominent human-rights lawyer, Biswajeet Tewari, in Nepalgunj.

A tall, serious-faced Nepali with thick black hair and a belly, Tewari had been working in the city for fifteen years, and had the clout to get a response when he phoned the police on Jagram’s behalf. They were remarkably prompt. Sajid and Bhola were taken into custody at the nearby Vada Prahari police station. Jagram’s group were made to go with them, and shown to a room of their own. Since the children had been trafficked from India, the Nepali police had to involve the Indian authorities.

Inside the station, a handcuffed Sajid beckoned Jagram over. Once more, he tried to cut a deal. “My daughter is getting married next month,” he whined. “And here I am, stuck. I won’t get out for twenty years.” He asked Jagram to tell the police that he’d taken money in return for sending his children to Nepal.

Jagram wasn’t having any of it. “I threw myself at your feet and you beat me with sticks,” he said. “Figure this out for yourself.”

The next day, the police drove the group across the border. When Jagtapa saw her sons, she wept. It had been three months since they had disappeared. They were injured, frail, and filthy. She washed them with laundry soap and fed them a meal of parathas and vegetables.

Sajid and Bhola were in jail for fifteen days before they were released on bail. The status of their case is a mystery. Reshma, Bhola’s wife, told me that her husband never heard back from the Nepali police. He doesn’t have a lawyer and has not returned to Nepal.

The lack of interest on the part of the Indian police in pursuing the matter reflects a widespread indifference to the problem of trafficking. The attitude is one reason why, in 2014, one year after the introduction of tougher codes, only 720 human-trafficking reports were registered in the entire country. The number of child-labor complaints was lower still — a mere 147, according to B.B.A. figures. If Sajid and Bhola’s case had been investigated, Ribhu believes, the pair would have been sent to prison for the rest of their lives.

It’s equally unlikely that the men will be charged under Nepali law. When I went to Nepalgunj and met with the police officer now in charge of the Vada Prahari police station, he was unable to give me any information. If a report on the arrests had been filed, he said, showing me to the door, “the rats have eaten it.”

Two years after the kidnapping, in April 2015, a 7.8-magnitude earthquake struck Nepal, affecting more than a quarter of the country’s people. A second earthquake quickly followed. Most of the initial deaths took place in Kathmandu and the surrounding valley. But when I visited the brick kilns three months later, I was told that although there had been injuries, no one had died. “We had shut down the previous month,” Khaimali explained.

This annual ritual, carried out in anticipation of the monsoons, saved hundreds of lives. The financial losses were another matter. More than 95 percent of the kilns suffered damage, Khaimali said. Indeed, when I entered Bhaktapur, I was met with the astonishing sight of dozens of chimneys with their tops lopped off, looking like stubbed-out cigarettes.

Two months after the earthquake, UNICEF released a statement that warned of a possible surge in child trafficking. The organization was working with the Nepali government to strengthen checkpoints throughout the country. A few months earlier, the Indian government slashed investment in children’s education and health to 3.26 percent of the yearly budget, down from 4.52 percent the previous year.

In Kudiya, life has entered a familiar groove. Akhilesh and Nakshed are enrolled in a new school, but it isn’t much better than the one they were in before. “The master’s no good,” Akhilesh complains. His ear is damaged, and sometimes he has trouble hearing. Like Nakshed, he is waiting to grow up so he can leave Kudiya. He would like to go to Mumbai, where Amrit Lal has secured an apprenticeship at an embroidery factory.

The boys’ mother is now too old to work, her sons say. There is still little money for food. Jagram has new debts. He borrowed 50,000 rupees ($940) for his oldest daughter’s dowry. Hoping to earn it back quickly, he joined Amrit Lal in Mumbai and found work as a loader. He hasn’t bought back the land he sold to finance his trip to Nepal.

One of the first things that Bhola did on returning to India was visit the Guptas’ house. He demanded money from Jagram, reimbursement for what he claimed to have spent on them. He implied that he had atoned enough by spending time in jail and threatened to take the children once more if Jagram didn’t pay him. This was too much for Jagram. “If you take my children again,” he promised, “I will kill you.” Later, however, Bhola approached the boys with an apology. In tears, he swore that he had no idea that Sajid would mistreat them. Amrit Lal willingly forgave his neighbor. “He lied to us,” he told me, “but he is a poor man.”

Last summer, a visitor arrived in the area, sought out a new group of children, and made them an offer. Some of the boys were as young as ten, the same age as Akhilesh when he was trafficked. The villagers alerted the Guptas. “The man who took you away is back,” they said.

Everyone was by now aware of the ordeal that the seven boys had undergone in Nepal. When Amrit Lal, Nakshed, and Akhilesh arrived home, the entire village gathered to see them. They saw the marks on the boys’ bodies and the swelling on Akhilesh’s ear.

The Gupta boys sent word: Don’t go. He won’t pay you. That’s why he wants children.

But four of Sajid’s targets, like the seven boys before them, couldn’t turn down the trafficker’s offer. They went with him to Nepal.

Trying to understand why they would put their lives at risk, Akhilesh was at a loss. Finally, he said, “Maybe they were also greedy for mobiles.”