Emad Matti had not received a photograph of the hostages. Two months had passed, and several Iraqi Christian families that had been detained by the Islamic State in an old folks’ home in Mosul were still imprisoned. From Kirkuk, Matti had been transferring $500 each month to a bank to feed the families, and he was afraid that they were dead, or that his informant in Mosul, one of their captors, was planning to prolong their imprisonment and collect even more money before demanding an impossible sum to drop them at the Kurdish border. For now, though, Matti just wanted photographic proof that they were still alive.

He checked his watch, a gold Breitling made from the weapons of martyrs in the Iran–Iraq War. The phone rang. He put a finger to his lips.

“Who is it?” I asked.

“It’s the Islamic State.” He greeted his informant and put him on speakerphone so I could listen. “Okay, Abu Haydar. What happened to the pictures of the women and children?”

“I was there yesterday with Abu Hamid. Believe me, they are under high supervision but with Allah’s will I will send you pictures of them.”

“I will be very grateful, Abu Haydar.”

“You don’t have to thank me, it’s my duty. I give you my word and I keep my word, otherwise I will be responsible in front of Allah and in front of you.”

“I know you keep your promises. What you are doing is a very good deed.”

“And you too, this will be my promise to you, no one will touch them.”

“May God protect your head.”

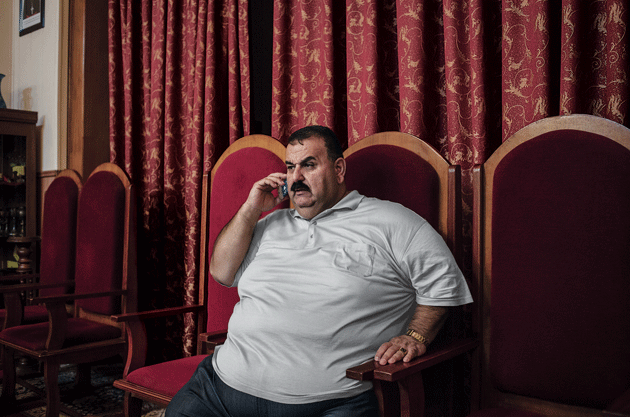

Matti, like the families he was trying to rescue, was a Christian. At fifty, he weighed more than 400 pounds, the result of a hormone disorder. His stomach, which was as wide as a hula hoop, pushed his legs apart when he sat. His pink feet swelled beneath the straps of his sports sandals and his watch fit as tight as a rubber band. Once, he’d flown to Amman, Jordan, to have fat surgically removed. It quickly grew back. He suffered from circulation problems; rolling up his pant leg, he showed me his purpled calves and skin that had turned black around his knee.

Three days later, from his office in a church in Kirkuk, Matti tried calling Abu Haydar for another update. Abu Haydar’s wife answered the phone.

“He can’t talk now, he’s praying,” she said. “He’ll have to call you back.”

Matti hung up.

“I don’t like these new Daeshis,” he said, using an Arabic term for Islamic State fighters. “I miss Abu Yaqin. He was such a helpful Daeshi.”

We were talking with Hormuz, a Christian man whom Matti had recently helped free. “I remember Abu Yaqin,” Hormuz said, twisting his hands nervously as though he were trying to wash something off them. “He was a short man with a beard and no mustache. A very nice Daeshi.” Hormuz looked up at me. “You don’t believe me? There are eight million people under the rule of Daesh. Certainly you can find good people there.”

Matti agreed. “You know,” he said, “most Daesh keep promises.”

Since the rise of the Islamic State in 2014, many Iraqi citizens had come to treat the militant group as they would any local government. Matti, like everyone else, had adapted. Plus the political affiliations of those he worked with were often less coherent or fixed than they might seem to the outside observer. Two or three of Matti’s sources in Mosul, a city around 100 miles northwest of Kirkuk, were Arabs employed by the caliphate. “They’re definitely Daesh, but I cannot say they are with Daesh because I’ll be accused of working with terrorists.” He also had informants on the ground in Kirkuk. “But these people aren’t participating in terrorist activities,” he explained. “And even if you torture me or kill me, I won’t give up their identities.”

When Matti invited me on a tour of the neighborhood, I asked about security. “The message has already been passed to ISIS that you’re here,” he said. “But don’t worry. I guarantee I could bring even you in and out of the Islamic State.”

A hundred and fifty miles north of Baghdad, Kirkuk straddles the border of Iraqi Kurdistan, a semiautonomous region, and the rest of Iraq. The city is a disputed territory; the Kurds say it belongs to them, while Iraqi Arabs say it belongs to Iraq proper. For decades, local Arab, Kurdish, and Turkmen communities have struggled for control over the land and its oil. To the northwest burns the eternal fire of Baba Gurgur, which is fueled by a vast oil field and looks, from a distance, like an entrance to the underworld. Many say it’s the fire into which King Nebuchadnezzar cast three Jews as punishment for their refusal to worship an idol.

During the rise of the Islamic State, the Kurds seized the opportunity to secure control of Kirkuk and other disputed territories. The southern portion of the city became the front line between the Islamic State and Kurdish forces, known as the peshmerga, which have been more successful at resisting the militant group than the central Iraqi government. Anyone crossing from the caliphate into Kirkuk is required to surrender themselves to the peshmerga at the Maktab Khalid, the gate between the territories.

Along with other former hostages, Ghaseon Patros Malko (third from right) attends a special service at a church in Kirkuk. She and her family had been living there for several months

Over the past two years, more than 125,000 Iraqi Christians had been forced from their homes and had moved to government camps, caravans, and construction sites across the relative safety of Kurdistan. In an effort to preserve a semblance of the Christians’ community and culture, Matti and his church were trying to resettle those from Mosul and the Nineveh plains—long home to Iraq’s Christian population and now occupied by the Islamic State. Matti used church funds to support around 500 families in Kirkuk and the nearby city of Sulaymaniyah. The money came from Iraqi, European, and American donors. In addition to financing the relocation of Christians, Matti used the funds to pay informants to locate and ransom Christians who had been kidnapped by militants. This activity, Matti told me, was unknown to the donors. Once the hostages were free, smuggling routes controlled by the fighters were the only way to bring them into Kirkuk.

These weren’t Matti’s first dealings with terrorists. During the American war, when Al Qaeda abducted ten Christians in Kirkuk, Matti negotiated with the kidnappers and paid $100,000 for the hostages’ release. After police intervened and disrupted his procedures, the militants shot one of the hostages in the head; Matti received a video of the execution. (The rest were freed.) More recently, he has supported refugees fleeing from Syria to Iraqi Kurdistan. When Mosul fell to the Islamic State, in June 2014, Matti realized he needed more help. He approached the archbishop of the Chaldean Catholic church in Kirkuk, a gray-haired man named Yousif Thomas Mirkis, and the two began collaborating. (The Chaldean church is made up mostly of Aramaic speakers who trace their ancestry to Iraq and Syria.)

The hostages Matti was rescuing were cheap compared with kidnapped Westerners. The Islamic State prices its hostages according to country of origin. Western hostages sell for millions; Iraqi Christian hostages cost just a few thousand each. Matti had ransomed eighty hostages so far; eighteen of those he paid for with his own money. (His regular income came from his work as a war photographer for a Western news organization.) The rest were purchased with church funds. I calculated that Matti and Mirkis had channeled at least half a million dollars over the past sixteen months into the hands of Islamic extremists.

The Chaldean church in Kirkuk, where I visited Matti in October 2015, was a sprawling granite compound the size of two football fields. Pink flowers bloomed in the courtyard and cats slept on warm walkways. A glinting obelisk listed the names of Christian martyrs. Recently released Christian hostages slept on thin mattresses or rested in the shadows of a statue of the Virgin Mary. The church was across the street from a mosque, and on Fridays the Muslim call to prayer echoed through the nave.

The church compound had become at once a refugee camp, a psychiatric ward, an orphanage, and a command center. Inside, construction workers toppled a shack to make way for another school building. Widows suffered through weeks of boredom in front of the television. The children watched Paris Fashion Week on TV and kicked their legs to the show’s techno beats. Matti provided the church with security, new mattresses, and a kitchen stocked with cooking supplies. (The refugees cooked together: for lunch they had one option and for dinner two.) The women’s dorm had a twenty-four-hour street camera that the women monitored on a television screen in the lobby. Residents had prepaid shopping cards to use at local stores. At the church school, nuns prepared tests for Muslims: Who was the first suicide in Islam? What does the Prophet say about destiny? They had a separate test for Christians: How do you define belief? What is God hiding in the pages of the Bible?

Matti allowed only the most traumatized former hostages to live within the compound walls. Among them was Ghaseon Patros Malko, who paced a storage room in a pink tracksuit with her arms crossed. Malko had been living in the compound for the eleven months since Matti had brought her family into Kirkuk. She had two daughters, Sidra and Sarah, and a son, Aboud. Her mother wept loudly and her father quietly. Her mother was a small woman with a curved back. She wouldn’t stop pacing and babbling to God. Her father lay on a foam mattress. He patted his eyes with tissues and piled the refuse around him. He couldn’t walk. His legs had stopped working after his son was kidnapped by the Islamic State.

“Greetings from God,” Matti said to Malko when he introduced us.

“Where’s God?” she asked.

Matti was born in Kirkuk in 1966. During the Iran–Iraq War, when he was twenty, he was an officer in the command force of Saddam Hussein’s Republican Guard in Faw, a subdistrict of the province of Basra. He and his fellow soldiers drank water from a creek clogged with corpses and ate snakes. One day, the general of his unit was on a helicopter, yelling through loudspeakers and encouraging his men to attack the Iranians. Matti was with his close friend Walid. Matti asked Walid to leave with him because rocket attacks were going to start, but Walid wanted to stay in the fight. He was on his way to a trench when a rocket hit him. The shrapnel left holes all over his body and tore open his calf. Matti carried him to a car. On the drive to the hospital, Walid announced that he was going to die. He asked Matti to look after his children. Walid took Matti’s hand, put it in his mouth, and bit down until it bled. Then he died.

Matti tried to help Walid’s nine children for several years, but eventually lost touch with them. After the war, he trained Special Operations recruits. Part of the process was learning how to behead small animals. He taught the men to crack the spines with their teeth. Sometimes Matti would set a rabbit free, and whoever captured and ate it alive would get a week of free rent.

In 1991, he married, and eventually had children of his own. To make money he sold watches. He bought Breitlings from pilots for six grand and peddled them to rich people for even more. Other watches that he sold had been given as gifts to high-ranking Baathists; they had tiny photos of Saddam on them.

In 2003, Matti began working as a combat photographer, and after the American invasion, he embedded with coalition forces to photograph the most violent episodes of the conflict. Throughout the new war, he saw his friend Walid everywhere.

Much of his activity now seemed driven by his memory of Walid. “When the bomb comes,” Matti told me, “I take the photo, and when I’m done I set the camera aside and start saving people.” He packed medicine, gauze, and tourniquets. “Every time I see a picture of the bodies in the pickup I cry. Sometimes we find people without heads.” (Several sources told me that Matti spent so much time saving hostages that he had started paying impoverished Iraqis to take the photographs for him.)

Matti was always working, even on Friday, the Muslim day of prayer. He went to bed at two or three in the morning and was up by six. “There’s no love story,” his wife told me. She said he was never home. She knew about his operations—he told her everything. He often tried to share his photos of bombs and I.E.D.’s with her, too, but she refused to look.

Matti knew everyone and everyone knew him. He nurtured a mythology about himself that others had come to believe as well. Kirkuk locals called him the Godfather. Ismail al-Hadidi, an important Sunni sheikh in Kirkuk, told me, “If ISIS comes to Kirkuk, we might be in danger. Everyone might be in danger, but not Matti.” He was never questioned by the police when he entered a crime scene. In December 2013, attackers armed with grenades and assault rifles captured a mall in Kirkuk, took shoppers as hostages, climbed to the roof, and started picking off people on the street below. Matti, who was snapping photos, warned a policeman not to walk in front of him. When the officer ignored his advice, a sniper blew his head off.

Matti relied on a complex network of support and cooperation across political, ethnic, and religious divides to complete his tasks. Ethnic Kurds, he told me, made up a great number of Islamic State loyalists in Mosul, and Matti had known a lot of families there before the rise of the caliphate. For nine years he had sold antiques in Mosul and surrounding areas, during which time he expanded his network of local tribal leaders, many of them Baathists, loyalists to the Saddam regime, like Matti himself and like many caliphate leaders. Networks such as Matti had were part of what made Baathists so valuable to the militant group. A number of senior Islamic State leaders were drawn from the top ranks of the Baathists, including Abu Muslim al-Turkmani, who was a senior Special Operations officer and member of military intelligence in Saddam Hussein’s army. (Al-Turkmani was killed in August 2015.)

Matti had never been arrested, but had been accused by residents of Kirkuk of working with the Islamic State. “I don’t care,” he said. “I’m doing it for the high purpose of humanity.” It had been this way before, too. During the American war, the chief of police in Kirkuk received a report alleging that Matti had cooperated with Al Qaeda and other extremist groups in the area. The chief called Matti and started laughing. “If the man submitted the application and mentioned a Muslim,” he said, “it might be reasonable, but you’re a Christian man!”

“Most Daesh don’t know I’m a Christian,” Matti told me. “I don’t even look like a Christian. If Daesh comes to Kirkuk, I’m totally safe. I’m Sunni with Sunni, Shia with Shia.”

Matti used to travel the half hour to the front line two or three times a week to pick up Christians and escort them back to the church. But his relationship with his intermediaries in the Islamic State had been deteriorating slowly, for various unrelated reasons.

The problems began, Matti said, with the influx of foreign fighters. Matti explained that under the Kurdish and Iraqi emirs (local Arab leaders) who first joined the militant group, Christians were spared execution if they converted to Islam or paid a tax. (Yezidis, another religious minority in Nineveh, were simply killed.) But when foreigners from Tunisia, Yemen, Libya, and Saudi Arabia began arriving in 2015, conditions for Christians worsened further. Matti especially disliked the Tunisians, who had harsher policies than the other fighters. Treatment was never consistent. Christians were slaughtered en masse by some Islamic State members even as emirs in sharia court allowed others to pass through checkpoints and enter free Iraq.

Peshmerga soldiers hold their position on a railway bridge near the Maktab Khalid. Air strikes by the U.S.-led coalition forces had partially destroyed the bridge

In November 2014, after militants from the Islamic State blew up the cell-phone towers outside Mosul, it became difficult for Matti to even contact his informants. Coalition air strikes increased along the buffer zones. Abu Yaqin, Matti’s most trusted informant, disappeared. To protect his project, Matti stopped answering calls from unknown numbers. He started using Viber, an encrypted messaging app that made conversations more difficult to hack, and memorized people’s numbers—more than a hundred—instead of saving them in his phone.

Only one member of the Islamic State had betrayed him during a hostage exchange. En route from Mosul to Kirkuk, the operative stopped the car, pointed a gun at the prisoner’s head, and called Matti to demand $4,000. (The original deal had been $1,000.) If Matti didn’t pay, the operative said, he’d kill the woman and toss her body into the desert. Matti said he would pay. When the men met, Matti handed over a stack of bills. “Do you want me to turn him in?” he asked the hostage. She told him not to bother; it wasn’t worth it. Matti was relieved. He didn’t want to compromise his relationship with Daesh.

Matti had rarely carried ransom money to the checkpoint. He handed cash directly to Islamic State operatives in Kirkuk or, more often, wired the money via Al Nakheel Exchange, a transfer service similar to Western Union. By March 2015, the Central Bank of Iraq had banned wire transfers to the Islamic State, but Matti managed to make himself an exception to the law.

The border crossing had also become more dangerous over time. In January 2015, Islamic State fighters attacked the Maktab Khalid and took seventeen peshmerga as prisoners. The men were taken to Hawijah, a city controlled by the caliphate that was about thirty minutes from the border. There they were locked in cages and paraded through the streets. Soon after, the militants hung the corpses of eight soldiers from the arched gateway at the Hawijah checkpoint. Coalition forces bombed Islamic State fighters at the crossing and retook the gate in a matter of days. Najmaldin Karim, the governor of Kirkuk, issued an order to close it. He didn’t allow families to come in or out unless they had permission to visit the hospital in Kirkuk.

This was a significant change. Previously, thousands of civilians, mostly Sunni Arab, crossed the Maktab Khalid each day. It was the only civilian crossing along a 600-mile front line between Kurdistan and the Islamic State. Every morning at six, families passed through to go shopping, attend school, visit relatives, or receive medical care in Kirkuk. Vendors and taxi drivers took advantage of this new milieu for business, and barbers set up shop to offer beard trims.

Travel had been made more difficult by the other side as well. At first, the Islamic State restricted travel only by former police and soldiers who might join the opposition, but soon even civilians were not allowed to leave without a good reason, such as receiving medical treatment or collecting pensions. By February 2015, civilians who wanted to leave had to submit the title for their home or car and agree to return within a specified period.

In September 2015, several hundred elderly residents were allowed to leave Mosul on pilgrimage to Saudi Arabia on the condition that they leave their property deeds as a guarantee. They planned to travel to Mecca and return to Mosul through Kurdistan. The week I arrived, Iraqi and Kurdish authorities refused to open the corridor from Kurdistan back into the Islamic State. The parking lot at Erbil International Airport was crowded with aged hajjis, tall, skinny men in white robes who napped on prayer rugs they had dragged onto the sidewalk. “Look,” my interpreter said. “It’s like the caliphate!”

When I reached Kirkuk, there were hajjis sleeping on the street there too. Matti visited them to learn what he could. They wanted to go home to Mosul. It was hard to understand why. The hajjis said that the Islamic State treated them much better than the Americans, who came and handcuffed them at night and pointed guns at the heads of their wives and children; at least the militants didn’t do that.

“But they’re throwing people off buildings?” my interpreter asked one old man.

“Yes, but they are homosexuals.”

“But they are beheading people?”

“Yes, and they were innocent, but their country is guilty. We asked the Americans to stop bombing and they didn’t respond. Nobody is executed for nothing! Most people in Mosul are really happy. By the way, it wasn’t a fall, it was a liberation.” One of the hajjis held out his hand and said that if he had America there, especially Dick Cheney, he would do this—and he squeezed his fingers into a tight ball to show how he would crush Cheney’s head like an egg.

“We regret that the Christians left Mosul,” he said, “and we hope they come back.”

None of Matti’s informants were entirely loyal to one group or another. If an informant were caught helping Matti, he would be punished by the Islamic State. Matti’s contacts were motivated partly by anticipation of a future upset in the balance of power. If Mosul were liberated soon and the caliphate destroyed, they would need Matti’s help as much as Matti now needed theirs. For his part, Matti would tell them anything to get what he wanted, even if it meant giving his blessing to the caliphate.

An informant named Abu Ibrahim called back an hour after Matti spoke with Abu Haydar’s wife, and we learned that Abu Haydar had been taken by Islamic State fighters to sharia court. Matti turned on the speakerphone. He eased into his conversation about the families in the old folks’ home by first discussing the pilgrims in Kirkuk. “How are you, sir? I was calling and wondering about these poor pilgrims from Mosul who are stuck here. Could you do something for them?”

“What can I do for them? They are in Kirkuk, right?”

“There are about six hundred of them stuck here. They are in Topzawa, in southern Kirkuk. Could you do something? I was with them yesterday. They have food and drink but they are in poor condition.”

“Why don’t they take other roads to come back to Mosul?”

“Because they have elderly people who cannot walk. How is the situation in Mosul now?”

“The situation in Mosul is very bad. Some of these dogs took Abu Haydar for interrogations. They wanted to know: ‘Where do you get the money? What are you doing? Why are you helping these people?’ Abu Haydar told them it was his own money. He lied to the court and said that he’d been helping them for a long time, even before the liberation of Mosul. But then the militants took him to sharia court anyway and kept him there for two hours.”

“Nothing serious, I hope?” Matti asked.

“I told him not to argue with them.”

“Please do not argue with them,” Matti said. “Thank God you are safe. May Allah always protect you.”

“They do have very bad people in the Islamic State sometimes. Imagine, they are worse even than the Jewish and Iranian people.”

“Okay, Ibrahim, God protect you. Just let me help you guys. If you can just send the pictures of the people in the home for the elderly.”

“I will do it. Listen to me. When I deal with somebody I do everything in an honest way. You are a journalist or something like that?”

“That’s true. I’m a journalist.”

“I checked your background. I know who you are. I will not deal with anyone randomly without a mediator. If I had doubts about you I wouldn’t be talking to you now.”

“With God’s will we will be honest with you guys.”

“That’s all we want. To serve these people here. It’s a humanitarian thing.”

“And we will not let you down at all.”

“So I will be dealing with you on trust, because I will be expecting that, too.”

“Of course,” Matti said. “It’s always mutual trust. Can you just send me a photograph of the people in the old folks’ home, please?”

“If you betray me, Emad Matti, no matter what you do, I will never trust you or do business with you again. Even if you brought me the Prophet Mohammed, I would not trust you. Even if you brought me yogurt from a bird, it would not impress me enough to trust you again. Let’s be clear about that.”

“Ask about me in all of Iraq,” Matti said. “In the whole of Iraq.”

“I told you from the beginning I checked you out,” Abu Ibrahim said. “And I’m talking to you without a mediator. I’m sure if the mother of my family were trapped in Kirkuk you would do the same for me. Is this not right?”

“That’s right,” Matti said. “And if you refuse to send the families out of Mosul, then who will save them?”

“There is no one,” Abu Ibrahim said. “But don’t think we are doing this job because of money. I swear to Allah even if you pay me tens of thousands of dollars I wouldn’t do that.”

“Don’t worry about that.”

“When I send the pictures, do not give them to anyone. Not even when you show the photos to relatives. Do not leave them around and do not give the family a copy, because the word will spread and the fighters will ask who took these pictures in Mosul, and they will kill me.”

“I’m a journalist and I’m in charge of internally displaced people here, but I swear to God I’ve never used any of the pictures in my job. And you can check me on that.”

“There is a famous Mosul idiom,” said Abu Ibrahim. “ ‘Put it in your hand and close your eyes.’ That’s what I expect from you, Emad, without having a mediator between us. But I’m telling you again. I’m going to send pictures today but do not get all of us in trouble because of the picture. Just show it to the family and take it away.”

“I’m grateful to you. You are blessing me with your kindness.”

“No, the blessing is only for Allah. We are all working for Allah.”

When I asked to meet Bishop Mirkis, Matti took me into a room with burgundy walls and tall velvet chairs. Mirkis was in a meeting with a representative from the Red Cross in Kirkuk, a Frenchman in blue jeans who wanted to donate laptops to relocated university students. The bishop had a Ph.D. in theology from the University of Strasbourg, in France, and a master’s degree in ethnology from Nanterre. He sat with his legs crossed, massaging a heavy silver crucifix. On the wall above him hung a photograph of himself with John Paul II.

Matti told me that the immigration office in Kurdistan gave an average of $800 per family to I.D.P.’s. But because of the Chaldean church, Mirkis explained, the situation for internal refugees was better in Kirkuk than anywhere else in Iraq. There were not many families in camps or construction sites.

After the Islamic State closed the University of Mosul, hundreds of students were unable to complete their studies. Matti and the bishop helped start an alternative university, advertised as the University of Mosul in Kirkuk. Students learned about the opportunity from social media. Mirkis told me that the church paid for some of the students’ expenses.

Most of the money came to the church from the French private sector, because of the bishop’s connections. “Just the other day,” Mirkis said, “we received a wire transfer from France so large the FBI stopped it.” The church also received donations from Catholic organizations in the United States, such as the Knights of Columbus, and from individuals in the diaspora in Detroit and California. It worked with Aid to the Church in Need in Germany, and with the International Red Cross in Kirkuk. The bishop also networked more informally to raise funds. “Nothing official,” he said, “just word of mouth.”

“Sometimes the donors just give the money,” Matti said, “and some give money for specific things, like infant milk, and some donors want a report on how their money has been spent.”

I asked if the church kept records of the donations. Matti said it did, but the bishop refused to give me access to the files.

“I like systems. I like discipline,” Matti said. “Except for financial things, because they take too long. If necessary I’ll get money in roundabout ways from church donors. For instance, doctors in Dohuk just called and offered to donate ten grand. So I took it. Most NGOs are very bureaucratic and slow. At least give me money to buy food. We have no category to classify our needs. How do you classify a ransom?”

The entrance to the Maktab Khalid was a long dirt corridor between high blast walls. A berm made by the Islamic State obscured the horizon, and just beyond was the border of the caliphate. A canal marked the beginning of the no-man’s-land. The air smelled of fumes from the North Oil Company, a sprawling complex just north of the canal, which the militant group had approached but never captured.

Thirty minutes away was desolate Hawijah, isolated by farmland. A generation of local children had stunted or paralyzed limbs, missing fingers or toes; in one case, a baby was born with two heads—all of which locals blamed on depleted uranium from American explosives detonated by the neighboring Forward Operating Base McHenry. The region was one of the most violent during the American war. In 2006, after the Bush Administration helped install Nouri al-Maliki as the prime minister of Iraq, Sunnis began to openly criticize his Shia-dominated politics. When Sunni protesters gathered in Hawijah in April 2013, Iraqi forces broke down the peaceful encampment and massacred dozens of unarmed civilians.

The month that I was on the ground in Kirkuk, fighters in Hawijah hung the bodies of deserters from a bridge. They dragged some residents alive through the streets until they were dead and beheaded others by sword in the market. On occasion, they forced civilians to donate blood to fighters.

The peshmerga base that controlled the Maktab Khalid was housed in an old Iraqi Air Force college. It had pastel-pink walls and a courtyard filled with flowers. The desert around it was controlled by Shia militias and marked with mass graves. Leafless trees and oil fires lined the horizon.

Here, I met Rasoul Omar, the head of all peshmerga operations in the region. He was a balding man with a wide pockmarked face.

“The situation in Hawijah is not good,” the commander told me. “There isn’t enough water or electricity, and there’s been an influx of people from Hawijah entering Kirkuk through smuggling routes. Sometimes women, children, and the elderly show up with bloody feet. Many die on the way.”

I asked about other smuggling operations on the border. He said he didn’t know of any. But many former members of the Iraqi army who had joined the Islamic State were now deserting the militant group and trying to get back into Kurdistan. Disillusionment had occurred as quickly as radicalization. In order to return home, deserters invented elaborate stories, feigned illness, forged medical reports, or overdosed on medication. Some dressed as women, others as students. They made fake I.D.’s or stole real I.D.’s from Iraqi security forces. Some arrived alone and surrendered in the glare of a peshmerga’s flashlight. A week before I arrived, three Islamic State fighters had contacted the peshmerga to let them know that they were on their way. The call was standard procedure at this point. The fighters dropped their weapons, removed their clothes, and walked naked into Kurdistan.

On January 17, 2015, two hundred Yezidis from Sinjar, the town in northern Iraq where most Yezidis are from, showed up at the Maktab Khalid. The peshmerga didn’t know whether they were freed prisoners or Islamic State infiltrators. Sometimes, the commander explained, the Islamic State simply dumps people at the border.

Occasionally, Omar himself negotiated to free hostages. Two months earlier, he had bought four Yezidi hostages from the Islamic State and reunited them with their families. “Yezidi girls are worth only twelve dollars,” he said. “It’s the same story every time: violence, violence, violence. One girl had been married thirty-three times.”

To obtain permission to pass through the Maktab Khalid, Matti first had to submit a request to Najmaldin Karim, the governor of Kirkuk, with information on the date of the exchange, the sector of the front line, the number of hostages, their names, and the state of their physical health. The paperwork took two days to process. Matti handed the letter he received to authorities at the peshmerga base near the Maktab Khalid. The authorities in turn provided Matti with another letter, which he handed to the frontline commander.

During operations Matti never carried a gun and never wore body armor. (It didn’t fit.) He usually dressed in slip-on boat shoes and a polo shirt with neutral slacks. When he freed Ghaseon Patros Malko, in December 2014, the operation required the assistance of a frontline doctor and several volunteers from the church.

The group took four cars and drove by starlight with their headlights off. They were shot at by machine guns, but it wasn’t clear who was shooting. At the peshmerga base, the letters were exchanged and the men traveled by foot to the front line, a thirty-minute walk. Because of recent clashes with the Islamic State, the peshmerga would not let the group cross. The checkpoint was crowded with families desperate to enter free Iraq, and the guards refused to allow anyone to pass until the fighting stopped.

After two days of waiting, Matti finally received authorization. He walked across land strewn with concertina wire and rubble toward Malko and her family, who walked from the other direction with their hands up. They met in the middle. The men carried Malko’s elderly father and turned back toward where they had come from.

On a Friday, two weeks after I had listened in on Matti’s conversation with Abu Haydar, the freed Christians at the church compound ate a late breakfast at a long table. Matti, who sat in the middle, broke bread for me. I was passed bowls of olives smooth as wet stone and piles of pink processed meats. Later that morning, terrorists threw a grenade through the window of the home of a reporter at a satellite-TV station. The locals hardly noticed. “Grenades are very common here,” Matti said.

After breakfast, I joined Matti on his Friday routine of visiting the Turkmen, Shiites, Sunnis, Christians, and Yezidis who were in Kirkuk. The telephone wires in town sagged with the weight of green Shia flags bearing the face of Imam Husayn ibn Ali (the grandson of the Prophet Mohammed), who was beheaded during the Battle of Karbala, 1,300 years ago. Abandoned military vehicles and empty lookouts lined the roads. Vegetation burned in the meridians. My interpreter translated street signs: “ ‘There is no God but Allah and Mohammed is his prophet,’ ” he said. “ ‘Mohammed is our guidance,’ ‘Do not forget to mention Allah.’ ”

I followed Matti into a Shiite mosque, where men were bowed in prayer. Matti dressed me in a priest’s robe and covered my hair in a hijab, and we gathered in a mirrored room around a scale model of Mecca. The cleric praised his congregation’s relationship with the Christian community in Kirkuk.

In the late afternoon, we returned to the church to check on the hostages in the old folks’ home. Matti sat on a couch in a room outside the kitchen to make his call. Abu Ibrahim still had not sent photographs of the families in his care. This was the first hostage situation Matti had negotiated, he told me, in which he had not received photos.

“Abu Ibrahim,” Matti said into the phone. “Listen to me. I sent five hundred dollars to your office in Bab Saray region in central Mosul. I called your boss and he didn’t answer. Therefore, I’m telling you that I’m sending the money today but you will receive it tomorrow.”

“Which name?”

“Same name your supervisor mentioned.”

“May Allah bless and protect you and thank you for that.”

“I don’t have to tell you again,” Matti said. “I desperately need photos of this family as proof of their existence.”

“I swear to Allah I will send it as soon as possible.”

“I’m also looking for Christina,” Matti said, “a girl who was sold and adopted by a family. I don’t know the name but I’ll give you the details later.”

“Look, my dearest brother, I will try my best to serve these people here.”

“That’s what I expected from you,” Matti said.

“My first point, I will try my best to help you. Secondly, I’m really in real danger here by doing this job, and thirdly—”

“All I need is to make sure these people are safe,” Matti interrupted. “I can feel from the tone of your voice that you are a very trustworthy and reliable man and I believe that I can trust you and I believe you are bringing food to them. And I’m sure you are treating them like your family members. You, Zaid, and Abu Haydar are very good with me.”

“Don’t worry at all. They are in my responsibility now. I will even provide security for them.”

“May God bless you and make you victors all the time.”

“We are not scared of anyone apart from Allah.”

“Yes, I know that.”

“This whole thing will end up in our benefit,” Abu Ibrahim said, in reference to the coming apocalypse.

“Inshallah,” Matti said. “God will work in your benefit, of course. Just try to reach this little girl.”

“Okay, I will do my best.”

“Okay then, goodbye.”

“May Allah protect you.”

Matti hung up. He was quiet for a moment. His shirt was damp with sweat and the circles under his eyes had deepened.

“The Daeshi are garbage people,” he said. “Baathists don’t do things like this.”