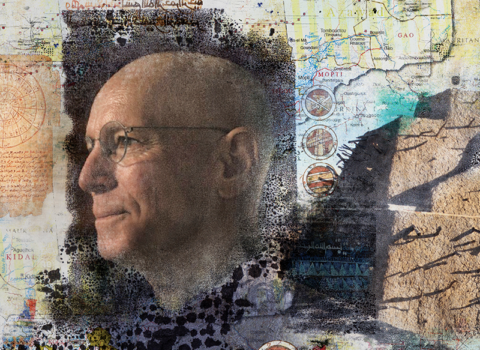

On the last Sunday in September 2015, the Reverend Stephen Blackmer stopped beside the stand of beech stumps where he had once performed the chain-saw Eucharist. He was leading a dozen or so members of the Church of the Woods on a contemplative walk. With his plaid shirt, decades-old custom Limmer hiking boots, and graying beard sans mustache, Blackmer didn’t look the part of a religious professional. He skipped nimbly over roots and rocks, turning around to laugh or make a point. His talk swept from exuberant to pensive to crass; at times he sounded like the theologically astute priest he was, at others like a mischievous wood sprite.

It was the first anniversary of the church, located several miles from the town of Canterbury, New Hampshire. A full lunar eclipse was expected that night, and Blackmer would be turning sixty in a few days. To celebrate these auspicious events, church members had planned a full day of activities: meditation walks, trail work, a Eucharist service, a bonfire, and, for those who still had energy, an eclipse-viewing party. When the group paused along the ridge of beech stumps it was midmorning; they were only halfway through a circumnavigation of the church’s 106 acres, which Blackmer described as a “labyrinth on a grand scale.” There was no church building, just woods. If you wanted to see the sanctuary, you had to hike.

The contemplative trek would take around three hours, but no one was complaining. Long walks in the woods are conducive to stories. Like the story of the chain-saw Eucharist. On a sunny, twelve-degree day in January, Blackmer had hiked into the Church of the Woods pulling a sled full of trail-clearing gear: axe, chain saw, oil, and gas. He wanted to clear new meditation trails, which mostly involved sawing up blowdowns and saplings. When he came to the ridge, he found it choked by the stand of young beech, so he cranked up his Jonsered and began felling trees. Over the next hour, Blackmer had a growing feeling that something wasn’t right. He hit the kill switch. Shit, he thought, I have utterly sinned and fallen short of the glory of God. It wasn’t cutting trees that bothered him. It was that he had been taking life after life “and had been utterly oblivious to the enormity of that act.” He had failed to remember that trees, even scrubby little saplings, are worthy of reverence.

Blackmer’s sled also held what he called his prayer kit: Communion bread, a water bottle full of wine, the Book of Common Prayer. Kneeling in the sawdust and snow beside one of the widest stumps, he spread out the elements and set up an altar. That day’s lectionary reading was from Isaiah. He read aloud:

I have swept away your transgressions like a cloud, and your sins like mist. Return to me, for I have redeemed you. . . . Shout, O depths of the earth! Break forth into singing, O mountains, O forest, and every tree in it.

He prayed the prayer of confession, consecrated the bread and wine, and offered them to his fellow congregants — the trees — before partaking himself.

Until nine years ago, Blackmer was an agnostic. After training as a forest ecologist at the Yale School of Forestry and Environmental Studies in the early Eighties, he founded and directed two successful conservation organizations in New England: the Northern Forest Center, where he managed a staff of more than a dozen and an annual budget of roughly $1.2 million, and the Northern Forest Alliance, a coalition of advocacy groups that succeeded in both shifting the local logging industry to more sustainable types of forestry and conserving millions of acres of land across Vermont, New Hampshire, New York, and Maine. At the time, Blackmer had no use for religion, especially for Chris-chens, as he called them — “those angry, antiscience, antienvironmental bigots.” He was fond of the bumper sticker that read born pretty good the first time.

Then, on a flight to Dublin in 2007, Blackmer heard the Voice. As the plane descended he looked down and saw a church steeple. Priest, the Voice said. You are to be a priest. He had heard the Voice before, and would hear it many times over the next year, but on the plane it would be the clearest. It was a sound he heard in his heart rather than his ears, but a voice nonetheless, and what it said was not a suggestion like, Have you ever considered a career in the ministry? You have the right set of skills. It was a statement of fact. You are to be a priest.

Then, on a flight to Dublin in 2007, Blackmer heard the Voice. As the plane descended he looked down and saw a church steeple. Priest, the Voice said. You are to be a priest. He had heard the Voice before, and would hear it many times over the next year, but on the plane it would be the clearest. It was a sound he heard in his heart rather than his ears, but a voice nonetheless, and what it said was not a suggestion like, Have you ever considered a career in the ministry? You have the right set of skills. It was a statement of fact. You are to be a priest.

There is more to Blackmer’s story, both before and after that flight over Dublin, but perhaps the most immediately startling thing is this: not until he arrived at divinity school, two years later, did he actually read the Bible. As a child, he’d read a few chapters of Genesis and heard the Christmas story. When he finally sat down and read the story to which he had committed his life, he was struck by how often the biblical writers engaged the very subject he’d spent his career studying: the land. The places in which the narrative occurred — mountaintops, hillsides, lakeshores, gardens — were not just stages on which the human story played out; they were actors in the story itself. He came to love the Psalms, and the frequency with which the psalmist used metaphors of nature, especially trees. In Psalm 92 the righteous ones “flourish like the palm tree. They are planted in the house of the Lord. . . . In old age they still produce fruit; they are always green and full of sap.” In other Psalms the trees of the fields clap their hands, shout for joy. When humans sing praises, they do the same thing. Nature is not inert. It was a revelatory idea.

There is more to Blackmer’s story, both before and after that flight over Dublin, but perhaps the most immediately startling thing is this: not until he arrived at divinity school, two years later, did he actually read the Bible. As a child, he’d read a few chapters of Genesis and heard the Christmas story. When he finally sat down and read the story to which he had committed his life, he was struck by how often the biblical writers engaged the very subject he’d spent his career studying: the land. The places in which the narrative occurred — mountaintops, hillsides, lakeshores, gardens — were not just stages on which the human story played out; they were actors in the story itself. He came to love the Psalms, and the frequency with which the psalmist used metaphors of nature, especially trees. In Psalm 92 the righteous ones “flourish like the palm tree. They are planted in the house of the Lord. . . . In old age they still produce fruit; they are always green and full of sap.” In other Psalms the trees of the fields clap their hands, shout for joy. When humans sing praises, they do the same thing. Nature is not inert. It was a revelatory idea.

In the Gospels, Blackmer found the most intriguing examples of divine encounter in nature. He kept noticing what he called “throwaway lines”: after Jesus had “dismissed the crowds, he went up the mountain by himself to pray” (Matthew), or “He would withdraw to deserted places and pray” (Luke). Sometimes Jesus went to a garden. Or a lakeshore. Or the Judean desert. The location varied, but the pattern was evident throughout the Gospels. Jesus went to the temple “to teach and to raise a ruckus,” but when he needed to pray Jesus fled to the countryside, to places unmediated by both temples and the religious authorities that governed them. Blackmer came to believe that direct contact with God is religion’s raison d’être, but one that’s often lacking in church. Of course one can experience God in a building, he concedes. But for at least some people, especially at this moment in history, there needs to be a practice of going into the wilderness to pray. And if one lives in New England, the obvious place to do that is the woods.

In the Gospels, Blackmer found the most intriguing examples of divine encounter in nature. He kept noticing what he called “throwaway lines”: after Jesus had “dismissed the crowds, he went up the mountain by himself to pray” (Matthew), or “He would withdraw to deserted places and pray” (Luke). Sometimes Jesus went to a garden. Or a lakeshore. Or the Judean desert. The location varied, but the pattern was evident throughout the Gospels. Jesus went to the temple “to teach and to raise a ruckus,” but when he needed to pray Jesus fled to the countryside, to places unmediated by both temples and the religious authorities that governed them. Blackmer came to believe that direct contact with God is religion’s raison d’être, but one that’s often lacking in church. Of course one can experience God in a building, he concedes. But for at least some people, especially at this moment in history, there needs to be a practice of going into the wilderness to pray. And if one lives in New England, the obvious place to do that is the woods.

Though affiliated with the Episcopal Church (the denomination in which Blackmer was ordained), the Church of the Woods is tied to a nonprofit organization called Kairos Earth, which Blackmer founded in 2013. In biblical Greek, kairos refers to an opportune or critical moment when God acts. In its first year, nearly nine hundred people attended services at the Church of the Woods. Of its thirty or so regular members, nearly half have graduate degrees. Many are medical professionals whose finely tuned diagnostic skills tell them that our planet is running a fever. As Wendy Weiger, a Harvard-trained research physician, told me, “Climate change is the biggest public-health crisis humanity has ever faced.”

Blackmer believes our ecological crises have precipitated a kairos moment. He sees a parallel with the Book of Jeremiah, in which the prophet describes a sense of impending doom as the Babylonians laid siege to Jerusalem in 587 b.c. “I looked on the earth, and lo, it was waste and void,” Jeremiah wrote, “and to the heavens, and they had no light.” On reading the book in seminary, Blackmer’s first thought had been, He’s talking about climate change.

Blackmer believes our ecological crises have precipitated a kairos moment. He sees a parallel with the Book of Jeremiah, in which the prophet describes a sense of impending doom as the Babylonians laid siege to Jerusalem in 587 b.c. “I looked on the earth, and lo, it was waste and void,” Jeremiah wrote, “and to the heavens, and they had no light.” On reading the book in seminary, Blackmer’s first thought had been, He’s talking about climate change.

As Western Christianity undergoes its identity crisis — a reformation or a slow implosion, depending on your leaning — a small but determined number of people like Blackmer are urging the church to seek God in the literal wilderness. They are calling for carbon repentance, but their credo is more nuanced than just slapping a fresh coat of Christian morality onto secular environmental politics; the Sierra Club at prayer this is not. At the Church of the Woods there is no action plan, no hive of online activity promising the earth’s salvation if only you click here. There is rather a summons, an invitation to carry contemplative practice and ritual enactment into one’s local ecosystem and thereby rediscover the awe and wonder that Moses experienced before the burning bush. By wooing Christianity back to its feral beginnings, Blackmer believes, we can finally confront the long trajectory of our ecological sin, and perhaps begin to change direction.

It was late morning at the stand of beech stumps. One of Blackmer’s congregants, an eighty-year-old retired physician named Peter Hope, had brought his GPS to map the network of trails. If he wanted to cover the distance before nightfall, he would have to get going. He set out walking, and the meditative trekkers followed in silence.

For the first-time visitor, there isn’t much to distinguish the Church of the Woods from any other forested part of southern New Hampshire. The previous landowner had cut the most desirable timber, leaving behind the stunted or misshapen trees in a practice known as high-grading. Though the forests are diminished, the bone structure of this land presents a walker with intriguing features: oddly shaped ridges, dells, and vernal pools. Something more than trees or squirrels resides there. The land tells a story about itself that, like braille, becomes legible only if you feel your way across the signs.

Growing on a dead hemlock stump was a dinner-plate-size reishi, a polypore known in China and Japan as the “mushroom of immortality” for its alleged immune-boosting properties. “Hey,” Weiger shouted up to Blackmer, “maybe we should apply for a religious exemption to eat psychedelic mushrooms. Like a peyote ceremony!”

Growing on a dead hemlock stump was a dinner-plate-size reishi, a polypore known in China and Japan as the “mushroom of immortality” for its alleged immune-boosting properties. “Hey,” Weiger shouted up to Blackmer, “maybe we should apply for a religious exemption to eat psychedelic mushrooms. Like a peyote ceremony!”

Weiger is not the sort who goes in for hallucinogens. After earning her M.D. and Ph.D., she worked for a number of years as a researcher at Harvard Medical School’s Osher Center for Integrative Medicine. Ever since living in Nepal in her twenties she had been drawn to meditation, and in 2003 she moved to Maine to pursue a more contemplative life. Once a month she drives the six hours down to the Church of the Woods.

Many of the church’s members are either former or current environmental activists. Wendy helped form a nonprofit that fought a protracted legal battle against Plum Creek Timber, a lumber company that wanted to develop 400,000 acres of Maine woods. Sue Moore, who is sixty-nine, was arrested alongside the environmentalist Bill McKibben at a rally against the Keystone XL pipeline in 2011. Blackmer fully supports lobbying and activism, but a common theme at the Church of the Woods is that activism isn’t enough. When he considered the difference between Christians protesting a coal plant and secular activists doing the same, he thought, There has to be something different in liturgy, giving the word its full extent of meaning in the New Testament Greek. Leitourgia gets translated as “worship or service to God,” but it can also be parsed as “the work of the people.”

Many of the church’s members are either former or current environmental activists. Wendy helped form a nonprofit that fought a protracted legal battle against Plum Creek Timber, a lumber company that wanted to develop 400,000 acres of Maine woods. Sue Moore, who is sixty-nine, was arrested alongside the environmentalist Bill McKibben at a rally against the Keystone XL pipeline in 2011. Blackmer fully supports lobbying and activism, but a common theme at the Church of the Woods is that activism isn’t enough. When he considered the difference between Christians protesting a coal plant and secular activists doing the same, he thought, There has to be something different in liturgy, giving the word its full extent of meaning in the New Testament Greek. Leitourgia gets translated as “worship or service to God,” but it can also be parsed as “the work of the people.”

This need to find a new path through liturgy and contemplation was true both of seasoned activists like Blackmer and Weiger and of younger members such as Rachel Field, who had looked at the available activist responses to the ecological crisis — secular or faith-based — and found them wanting. For two years Field worked for the Center for the Environment and Society at Washington College, in Maryland, where she and her co-workers banded 14,000 migratory birds a year. She loved the work, but found it difficult to speak about faith in that science-heavy environment, so eventually she enrolled at Yale Divinity School and began attending the Church of the Woods. She was considering returning to Maryland to start a Church of the Marshes, where she might offer up the bread and wine among the egrets and plovers on the tidal flats of the Chesapeake Bay.

This need to find a new path through liturgy and contemplation was true both of seasoned activists like Blackmer and Weiger and of younger members such as Rachel Field, who had looked at the available activist responses to the ecological crisis — secular or faith-based — and found them wanting. For two years Field worked for the Center for the Environment and Society at Washington College, in Maryland, where she and her co-workers banded 14,000 migratory birds a year. She loved the work, but found it difficult to speak about faith in that science-heavy environment, so eventually she enrolled at Yale Divinity School and began attending the Church of the Woods. She was considering returning to Maryland to start a Church of the Marshes, where she might offer up the bread and wine among the egrets and plovers on the tidal flats of the Chesapeake Bay.

The forest trekkers arrived at the Altar, a small clearing where the church holds its services. The altar itself is a white-pine stump festooned with British soldier moss. Field counted the rings and reported that the tree was more than ninety years old, ten years older than Peter Hope. This would have been one of the trees felled when the land was high-graded. Someone placed Indian cucumber on the altar as an offering, another set down the reishi.

The Altar is the spiritual, if not the actual, center of the church. It is here that Blackmer offers Communion to his peripatetic flock. There is a worry among certain mainline Christians that once you start dabbling in nature, you’re on the slippery slope to paganism, but Blackmer is no druid. He found years ago that the vague, earth-based spirituality he’d lived with for most of his life wasn’t enough, and now considers himself a solid Trinitarian. But that makes it sound as though his conversion was the result of a spiritual shopping trip, when the better comparison would be a boxing match.

In 2005, Blackmer had been an environmental activist for nearly three decades, and he found he couldn’t sustain it any longer. Despite some successes, the overwhelming reality of climate change made him feel as though the movement was fighting a losing battle. A friend invited him to a vision quest in California’s Inyo Mountains, a land of extremes. To the west stands the highest point in the contiguous United States, to the east lies the lowest. Just north grows the oldest tree on earth. An auspicious place to receive a vision.

Blackmer’s quest ended in a solitary four-day fast on a mountain, a time full of signs and portents. On his last night, in total darkness, he attempted a walk around the mountain. With no trail to follow, he came to a place where he had to choose between two routes. He asked aloud for a sign, and in the next moment saw a shooting star. “I mean, it was just silly,” Blackmer laughed. He followed the star. Groping along in the dark, he stumbled into a deep gully and ran into a rock wall. There appeared to be no way out. “I was scared out of my freaking mind,” he said. Feeling his way along the wall, he eventually came to a lone piñon pine silhouetted against a black sky, a tree he had seen before. He knew how to get back. In the small hours of the morning, having walked many miles, he finally stumbled into camp. Blackmer believed that “something utterly profound” had happened in his life, but he had no clue what it meant. He lived with that uncertainty for the next two years and fell deep into depression. That’s when he first heard the Voice.

While meditating one morning, Blackmer heard: The meaning of your journey around the mountain is that you must turn around and go the other way. You must follow the same path, but going in the other direction. This is a spiritual path. He tried Buddhism, which seemed like a logical fit — he had been meditating for several years — but it just didn’t take. Sometimes he woke in the night with horrible anxiety, and the Voice would say, Rest in the crucible of anxiety. It will destroy you. It will transform you. Then came the flight into Dublin.

While meditating one morning, Blackmer heard: The meaning of your journey around the mountain is that you must turn around and go the other way. You must follow the same path, but going in the other direction. This is a spiritual path. He tried Buddhism, which seemed like a logical fit — he had been meditating for several years — but it just didn’t take. Sometimes he woke in the night with horrible anxiety, and the Voice would say, Rest in the crucible of anxiety. It will destroy you. It will transform you. Then came the flight into Dublin.

In the months following the trip, Blackmer resigned from the Northern Forest Center and began to experience visions. He dreamed he saw a triptych of the face of Christ, except the face in all three panels was his own. At the urging of a friend, a fellow forester and conservationist who also happened to be the only priest he knew, Blackmer visited the Society of St. John the Evangelist, an Episcopal monastery in Cambridge, Massachusetts. He spent three days in utter silence and anonymity, feeling like a foreigner. He saw the monks bowing before they passed the altar and thought, I can’t bow to this altar, to the white linens and shiny goblets. Then he realized that the monks were simply bowing to the mystery. That he could do. On the third day, Blackmer heard the brothers chanting the Psalms and something inside him broke. Their beauty, the chanted words from three thousand years ago, shattered his defenses. He wept. He took the Eucharist for the first time in his life. But when he returned home, he still resisted attending church.

Two months later, Blackmer and his wife were visiting his brother in the cloud forest of Costa Rica. One morning, meditating alone in the house, he heard a knock at the window. He checked and found nothing there. When he sat down he heard a second knock, this time a bit louder. Again, nothing. This happened a third time, and then he heard the Voice say, Let me in.

Oh shit, he thought, it’s Jesus. It was Easter Sunday.

Like Flannery O’Connor’s Hazel Motes, who saw Jesus “move from tree to tree in the back of his mind, a wild ragged figure,” Blackmer was a man haunted by God. He often laughed at the absurdity of it all. Vision quests, voices, shooting stars? Knocks at the window? He was amazed too at his former self, at the strength of his resistance — “heels dug in every inch of the way.” He wasn’t going to church.

But after so many rounds in the ring, he surrendered. He began reading about Christianity. He wanted to find out “if there was room for me in this hierarchical, antiquated, rule-bound, antienvironmental faith. Do they have people like me?” The more he read, the more he was convinced the answer was yes. One year after his flight to Dublin, he was baptized. Four years later, in 2012, he finished divinity school. And a few months after that, he purchased, with help from a generous donor, the 106 acres that would become the Church of the Woods.

Following a long respite at the Altar, the trekkers took a fork in the trail. Blackmer stooped, picked a handful of wintergreen leaves from the understory, and passed them around for people to chew. They nibbled, walked, and prayed.

After crossing a century-old dam now overgrown with vegetation, the group paused to observe a young hemlock. Its trunk stood atop an upright protrusion of roots, making the tree appear as if it had legs.

“Maybe it’s an Ent,” Field said, referring to Tolkien’s mythical tree creatures. “Stand back, it might start walking.”

They climbed another small rise. “It’s an odd piece of land,” Blackmer said, “like this funny little ridge we’re standing on. But that’s fitting, because we’re an odd bunch of people.”

One of the church’s members goes by the name of Sister Athanasius. An Episcopal nun in California since the Seventies, she chose her name when she read about the bishop of Alexandria who was consecrated, in a.d. 326, only after vigorous resistance. Sister Athanasius had not wanted to become a nun, which explains in part why she and Blackmer get along so well. In addition to their attempts at dodging the divine, both speak their minds freely, often employing a most impious lexicon. More important, they are equally smitten with the natural world. On Blackmer’s coffee table he keeps a book-length poem given to him by Sister Athanasius: W. S. Merwin’s Unchopping a Tree. The poem is an imaginative exercise in arboreal reconstruction. The narrator issues directives: how to rig the tackle for lifting the bole, how to reattach the broken trunk, how to glue back every splinter, chip, and piece of moss, until reaching this final, devastating line: “Everything is going to have to be put back.”

The walkers came to the boundary of the church’s property. Someone wondered aloud why the border still had barbed wire, and Sister Athanasius chuckled and said, “So the prisoners won’t escape.” Suddenly everyone grew quiet. The Canterbury-pilgrim mood of jocular ease had given way to something else.

The walkers came to the boundary of the church’s property. Someone wondered aloud why the border still had barbed wire, and Sister Athanasius chuckled and said, “So the prisoners won’t escape.” Suddenly everyone grew quiet. The Canterbury-pilgrim mood of jocular ease had given way to something else.

Before them lay a bowl-shaped depression, a tiny clearing encircling a dried-up vernal pool. Moose tracks led into the muddy water. A gentle slope rose up and away into thick woods. Fallen hemlock and paper birch lay crisscrossed over the clearing like giant pickup sticks. Trees that had fallen and were not going to be put back. The air was still. Smells of pine, rotting duff, the dank musk of humus. An ordinary forest clearing, and yet more than ordinary. The kind of place that you might chance upon as a child while wandering in the woods, though if you were asked why you tarried there, or for how long, you couldn’t say.

Soon Blackmer would send them off for a period of individual contemplation, but before he spoke there was a long, palpable hush. Sister Athanasius slowly raised her palms to her temples. She gazed at the pools, the bits of sunlight dappling the glade, the dark mystery of the woods beyond. “Ahh, Jesus,” she said softly, “just look at that.”

The story of Moses and the burning bush is one of Blackmer’s favorite texts. In Exodus, the Lord appears to Moses in a bush that burns but is not consumed. “Remove the sandals from your feet, for the place on which you are standing is holy ground.” Blackmer often takes that literally, celebrating the Eucharist barefoot. Confronted with the threat of climate change, he believes, we must think of all ground as holy ground. Without such a recognition, there is no way out of our ecological woes. In the Eastern Orthodox tradition, the burning bush prefigures Mary the Theotokos, the God-bearer, who carried the Incarnate God inside her womb but remained unharmed. Blackmer thinks of the Earth itself as a theotokos. Would we clear-cut a forest or demolish a mountain or frack a field that bore the living God?

When the little band of pilgrims returned to the parking lot, Blackmer pointed out the church’s sole “relic,” a bent and broken aluminum ladder leaning against a tree, left behind by the loggers when they high-graded the place. It reminds him of Jacob’s Ladder, another favorite biblical story. Genesis recounts how Jacob lay down upon a stone to sleep and dreamed of a ladder that joined heaven and earth. Upon awakening, he exclaimed, “Surely the Lord is in this place — and I did not know it!”

A common theme in Blackmer’s conversations is that we’ve lost the face-to-face connection with God, the awesome, fearsome encounter that so often occurs in wild settings. Art, music, a beautiful sanctuary — all of those can be soul-stirring. But they can also obfuscate one’s connection to God. Nature strips away the human intermediary.

A hawk cried overhead. Peter Hope ambled over with trekking poles, backpack, and GPS unit. It was midday now, and after walking the property that morning with the contemplative hikers, he was off to take readings on the remaining trails. By the end of the day this eighty-year-old man would have trod seven or eight miles over this land of mounds and folds. Traversing the theotokos, praying with his feet.

Since the Industrial Revolution we’ve scaled up development to a tremendous degree, and even under the most optimistic scenarios we’re going to be dealing with climate change for centuries to come. Blackmer foresees a time of unimaginable suffering and grief. His faith tells him that on the far side of that suffering stands the tree of life, symbol of the resurrected world in which humans will have found their place in creation. There is no path to that perfect world, however, that does not involve hardship and death. “We’re not going to skate through this one untouched,” he told me.

Blackmer’s understanding of the Second Coming is not one in which Jesus returns to fix everything. His eschatology leans toward the Eastern Orthodox understanding of theosis: deification. Through the slow work of prayer and contemplation, a person becomes more like Christ, and Christ comes to dwell more completely within that person. “That’s the way Jesus becomes present,” he said. “It’s through our transformation. A spiritual death. And a rebirth.” What must die is the materialist worldview in which physical reality is viewed as just stuff: “The world is not merely physical matter we can manipulate any damn way we please.” The result of that outlook is not just a spiritual death but a real, grisly, on-the-cross kind of death. “We are erecting that cross even now,” he said.

Rachel Field also knows that humans are causing climate change and that the results will be catastrophic, but she wonders about our ability to stop it. She sees the human role as that of a witness, a provider of hospice care for the ecosystems we’ve damaged. Coming to a place that has been as heavily logged as the Church of the Woods is one way she can say to the land, Yes, we did this. And we are not going to leave you. She knows that this earth, this cosmos, will endure and will transform into something beautiful even if humans can’t survive on it. “Every time a creature is lost, a piece of God’s glory is leaving,” she said. “But it’s bigger than us.”

Though Blackmer freely acknowledges that some are called to activism and that such work is sorely needed, he himself has left that role behind, at least in the usual sense. Activism, in his view, too often becomes a mask for hiding undigested fear or grief. His work now is to change people’s consciousness rather than to affect policy.

Hearing Blackmer talk, one might wonder how a shift in consciousness can save a beleaguered planet. As environmentalist groups like 350.org have shown, it takes direct political action to achieve tangible results, such as the protests that managed to stop the construction of the Keystone XL pipeline, or Blackmer’s own efforts to preserve millions of acres of New England forest. It’s difficult to imagine achieving those results through an internal shift, but for Blackmer, the emphasis is on the activist’s starting place. The question is not whether one takes action, it is from what heart and mind one does so.

The church’s leitourgia, the work of the people, is first the work of prayer. The once-thriving Canterbury Shaker Village lies only a few miles east of the Church of the Woods, and for Blackmer the proximity is no coincidence. The Shakers’ connection to the land and their devotion to prayer left a spiritual presence that is still palpable. “Prayer transforms places as well as people,” Blackmer said. “You can actually feel it when you walk into a place where people have prayed for long periods of time. It is as if prayer has changed the molecular structure of a place.” Thus altered, the woods become a kind of inner sanctum in which we are faced with what the theologian Rudolf Otto called the mysterium tremendum. “The semi-darkness . . . of a lofty forest glade,” he wrote in The Idea of the Holy, “has always spoken eloquently to the soul, and builders of temples, mosques, and churches have made full use of it.”

The work of the people also includes the Eucharist. For Blackmer, “It is the act of taking into ourselves the body of He who died and went through death and came back.” Death and grief transmuted into love. That expression of hope in the midst of death is where, for Blackmer, the Christian faith comes into its own. “All of us go down to the dust,” he said, quoting the burial rite from the Book of Common Prayer, “yet even at the grave we make our song: Alleluia, alleluia, alleluia.” Death does not have the final word. Joy does. “That’s what Jesus was all about,” Blackmer said. “And if we forget that, then shit — we’re a sad, pitiful bunch. And we’re sure as hell not leading anybody to the Promised Land.” When he presides over the liturgy each Sunday, this priest in the trees, a sixty-one-year-old man still green and full of sap, carefully spreads his elements across the white-pine stump. He offers the first morsels of bread and the last sip of wine to the earth.

That Sunday evening, when most of the crowd had left the Church of the Woods, a dozen members huddled by the campfire and watched the lunar eclipse. The moon rose red above the trees. A super blood moon. It faded as it climbed, its face slowly adumbrated by Earth’s shadow. The fading orb seemed to glow from within. Just before the full eclipse, a luminous plane of light appeared on the moon’s edge. For a brief moment it grew bright. Then it was gone.

Though it began in a desert, Christianity is a faith haunted by trees. The story opens in a garden, in the center of which grows the tree of life. Ignoring that tree, Adam and Eve make for another — from which they pluck our downfall. The primal couple are hungry for knowledge and knowledge they get, but they soon find it’s a mixed bag. They eat the fruit and “the eyes of both were opened,” and lo, the beginnings of human consciousness. Of the tree of life we hear no more until the final chapter of Revelation, where we find it growing on either side of the river in the center of the New Jerusalem. Its leaves “are for the healing of the nations.” Between the Bible’s arboreal bookends stands a third tree, the cross at the center of the Christian story. Given their narrative prominence, the biblical drama stands or falls with the trees.

“The bulk of a tree,” writes Tom Wessels in Reading the Forested Landscape, “is mostly dead wood.” Other than the leaves, the only living part is the cambium, a group of cells a few millimeters thick that resides under the bark. The trunk may be lifeless and inert, but it’s still needed to provide structure for the growing cambium. The bulk of Christianity — whether it be ancient cathedrals or big-box megachurches — is mostly dead wood. The cambium of faith resides unseen, just beneath the surface, ever growing in new directions.

I had already been thinking a good deal about trees long before my visit with Reverend Blackmer. I’m surrounded by them, for one thing. Transylvania County, where I live, is aptly named. Trans, “through”; sylvan, “woods.” Trees thrive in this part of western North Carolina because it is a temperate rainforest, containing some of the greatest biodiversity in North America. The landscape here feels maternal. It swaddles you in its gentle folds, its swaying branches, the humid air of so much life breathing in, breathing out. Here I’ve taken to pondering the symbiosis between these forests and the Christian faith I attempt, and often fail, to practice.

That August, in Transylvania County, it began to rain. Right on through to Christmas, it rained: fifty-nine inches in all. Normally we average around seventy inches of rain a year. As the atmosphere warms, increasing the air’s capacity to hold moisture, that amount will surely increase. It already has. Two years earlier we had received 112 inches of rain. A few days after Christmas, on a day like so many other days that December — rainy, seventy-five degrees — I followed my three young sons down to the creek that runs near our house. The boys had been building a mud dam and were eager to show me their handiwork. On a winter’s day when we should have been sledding, my sons and I squatted beside a creek in the warm drizzle and played in the mud.

There is a word, coined by the Australian philosopher Glenn Albrecht, that describes the longing for your own home, not homesickness from a distance but the yearning you feel for a place in which you still live but which has become unrecognizably damaged by some extractive industry: “solastalgia.” We now speak of “shifting baselines” and the “new normal” — euphemisms that soften the blow of climate catastrophe. Perhaps this is our work now, to abandon the false linguistic signposts that lead us astray — “stopping” or “fixing” climate change — and instead find new words and stories and metaphors that will help us confront what is already upon us, and devote ourselves to what we might yet save. “The powerful metaphor,” Bill McKibben has written, “will be more useful than the cleanest engine.” As the Church of the Woods has discovered, such metaphors are already waiting in our religious traditions, claiming a power far deeper than the utilitarian “ecosystem services” or even the language of democracy. The question climate change poses is how to confront the enemy within, and that is not primarily a technological or political question; it is a religious one.

We have high-graded the world, taking the best and leaving the scrubby undergrowth. We now find ourselves chastened by the scope of our destructive power, yet still hungry for the awe and wonder we once felt before creation’s magnitude. The Babylonian invaders are approaching, and we have no choice but to face them — which is to say, face ourselves.

The search for God in a sacred grove recalls the Israelites in their tabernacle in the Sinai desert. That search cannot be contained by human walls, despite the solidity that Chartres or Notre Dame or the National Cathedral might suggest. If Christianity is going to confront climate change, perhaps it needs to rewild itself, go feral. What the faith has to offer first is not protest or activism, though it may lead there. It is leitourgia. The work of the people. And the work of the people now is this: Keep the land holy. Keep the carbon in the ground. Renounce the myth that this earth is a random assortment of bio-geophysical processes that can be prodded, manipulated, fracked, or drilled for our own purposes, however nefarious or benign. Approach with awe the theotokos, the bush that burns but is not consumed. Perhaps we begin by taking off our shoes.