I first heard the name Barack Obama in the spring of 2004, while visiting my mother in Chicago. As we sat around the kitchen table early one spring morning, I noticed a handsome studio portrait among the pictures, lists, cards, and other totems of family life fastened to the refrigerator door. “Who’s the guy with the ears?” I asked, assuming he was some distant relative or family friend I didn’t know or else had forgotten. “Barack Obama,” she answered with a broad smile. “He’s running for Senate, but he’s going to be the first black president.”

Politics in Chicago is a blood sport, and growing up, we followed it the way we did prizefighting. As my mother described the contenders in colorful detail, I accepted her judgment. There was something in her voice that morning that made me take special note. A tone usually reserved for her children and grandchildren. It was pride.

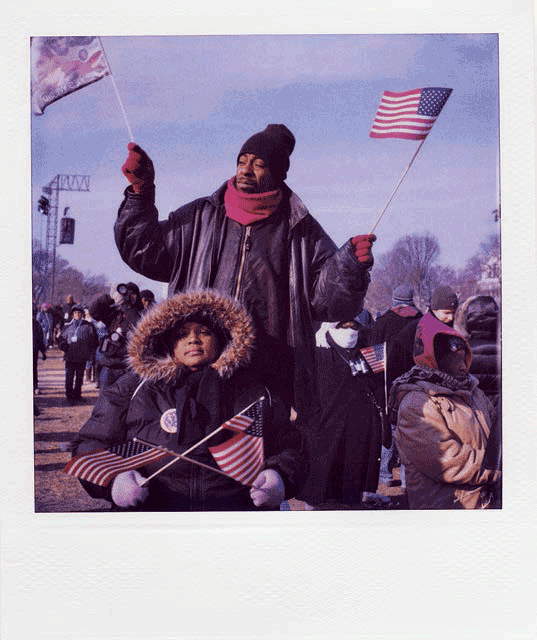

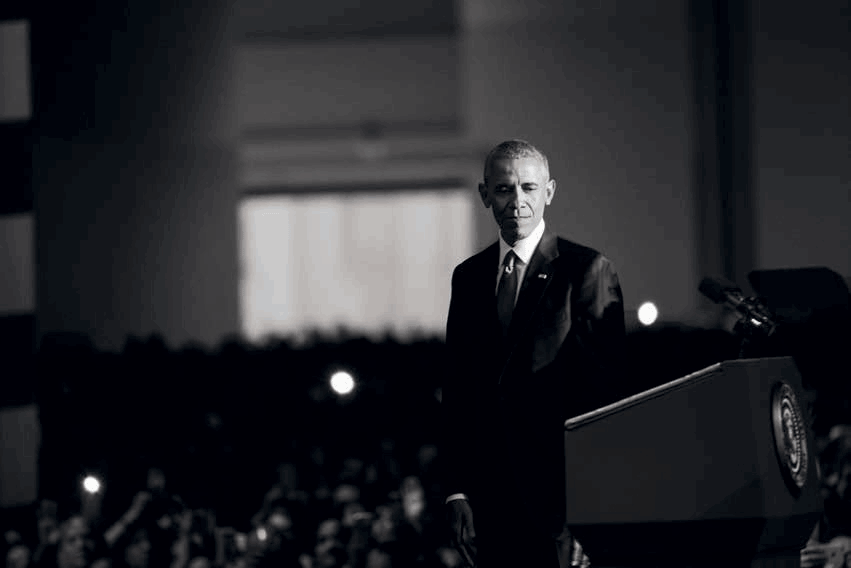

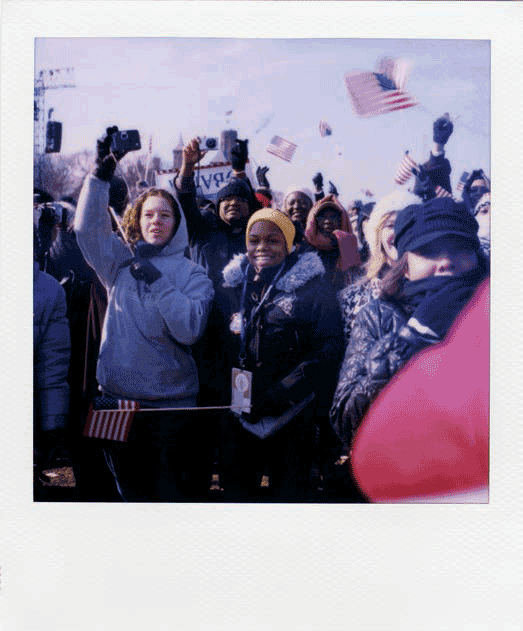

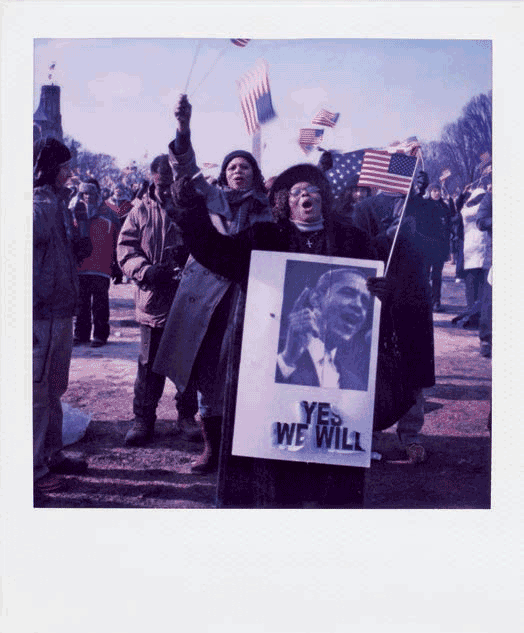

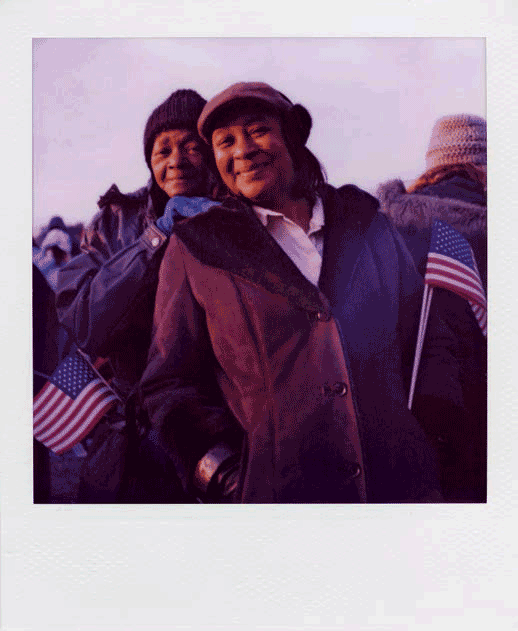

President Barack Obama at his farewell address, Chicago, January 10, 2017. All photographs © Jon Lowenstein/NOOR

Robert Kennedy, in a 1968 radio broadcast, predicted to the day when the first black president would be elected. “There’s no question about it,” he said. “In the next forty years a Negro can achieve the same position that my brother has.” When Kennedy made this pronouncement, the rate of social change was approaching a historic apogee, and his words reflect an unalloyed optimism, despite the murder of Martin Luther King Jr. less than two months earlier. (Kennedy himself would be felled by an assassin ten days later.) The concerted backlash against civil rights, which began under Nixon, had yet to pick up steam, and Kennedy spoke for many Americans when he insisted, “We are not going to accept the status quo.”

My mother, who migrated to the North with my grandparents in the 1950s after a childhood in the Jim Crow South, lived through those forty long years. As she spoke in the kitchen that April morning, I was struck by the difference in our perspectives. I was part of the first post-civil-rights generation, and had taken for granted that I would see an African-American president in my lifetime. She had seen the struggle firsthand, and feared that things would progress no further. Her certainty about an Obama presidency came less from her political astuteness, which is substantial, than from a deep conviction, shared with nearly every black voter, that needed it to be so. He had connected to her faith. Soon he would have a similar effect on 70 million others, of all races.

For people who had been denied the vote for most of this nation’s history, of course, seeing a black person elected to the highest office was a transfiguring experience. Obama himself was well aware of this. In his memoir Dreams from My Father, he recalls sitting in a chair in a South Side barbershop soon after his arrival in Chicago, listening to the other men discuss Harold Washington, the only black person ever elected mayor of a city that boasts the second-largest black population in America. “That’s how black people talked about Chicago’s mayor, with a familiarity and affection normally reserved for a relative,” Obama writes. The barber, an older man, explains to him that “people weren’t just proud of Harold. They were proud of themselves.” He added that you “had to be here to understand.”

That last comment haunted the young Obama. On a literal level, the barber was talking about Chicago. Yet his words also spoke to a generational and experiential gap that separated the new arrival from the middle-aged denizens of the barbershop. Could Obama put himself in their shoes? And hard behind that: could they accept him as one of their own?

I asked myself if I could truly understand that. I assumed, took for granted, that I could. Seeing me, these men had made the same assumption. Would they feel the same way if they knew more about me? I wondered.

Twenty-four years later, during Obama’s first presidential campaign, similar questions were posed by his supporters and detractors alike. Indeed, his identity was challenged in ways few if any candidates had experienced before. All the questions pointed back to America’s racial neuroses. But by 2008, four years after that conversation in my mother’s kitchen, it wasn’t only black people who had invested his candidacy with extraordinary hopes. In late September, during the closing days of the general election, I bumped into a white colleague in Manhattan as he was returning from a MoveOn rally. Like the majority of New York liberals, he had been a Clinton man in the primaries and was now newly converted to Obama’s cause.

“He’s going to end the wars,” my colleague said. “He’s going to close Guantánamo.” There was rapture in his voice and on his face, as if he had just returned from a revival. He had become a Dreamer.

“No,” I said, “he’s not.” Such claims seemed to deny the laws of political calculus, which are as immutable as the laws of thermodynamics. Just as France’s Indochine became Eisenhower’s Vietnam, then Kennedy’s, then Johnson’s, then Nixon’s, so would Bush’s wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, with their squandered lives and chaos, belong to the next president, whatever his personal beliefs. It was delusional to expect otherwise.

Still, as I gauged my colleague’s response — pained, crestfallen, belligerent — I realized I should have kept such thoughts to myself. Like many progressive white Americans, he saw Obama as a nearly magical figure. He nourished the hope, perhaps not fully articulated even to himself, that by casting a single vote he could not only right our economic ills and reverse our foreign misadventures but absolve himself of bigotry, complicity, shame, guilt. He wished to be, as the phrase goes, on the right side of history. Who could blame him? It is a history from which both blacks and whites wished to be redeemed — even if their pathways through it have often been mutually unrecognizable.

Slavery in England’s North American colonies grew up piecemeal, without design, really without much thought at all. It was first widely questioned during the Great Awakening of the mid-1700s, a catechism that also had a profound effect on Revolutionary thought. By the time the first Congressional Congress met, in 1774, religious feeling had fused so deeply with the theory of natural law that slavery was already viewed in many quarters as anathema to independence. Indeed, many considered abolition and independence as one and the same cause. During this period, writes the historian Winthrop Jordan in his influential study White over Black,

many Americans awoke to the fact that a hitherto unquestioned social institution had spread its roots not only throughout the economic structure of much of the country but into their own minds.

In short: Americans began to realize they had a race problem.

The economy of slavery found new momentum after the Revolution, largely because of Eli Whitney’s new technology and the cotton kingdom it engendered. Support for the “peculiar institution” grew entrenched across the South. But so, too, did the cry for abolition. The economic force and the moral counterforce developed in hostile tandem. The Civil War, in this view of history, was inevitable. “Nothing is more certainly written in the book of fate,” reflected Thomas Jefferson, the eighteenth-century poster child for the Cartesian mind–body split and the embodiment of all the young republic’s contradictions, compartmentalizations, and self-deceits, “than that these people are to be free.”

The emancipation both predicted and feared by Jefferson did eventually come. By then, of course, there had accrued three centuries of slander aimed at the intelligence, ethics, and plain humanity of black Americans. Stereotypes, most of them projections of white behaviors and fears, had hardened sufficiently to present real challenges when it came to education, employment, and housing. Race had come to dominate not only the social world but the deep interior of the white self.

Yet in some sense, the Constitution had worked. Its august machinery had allowed a cruelly compromised society to correct itself — and had held the nation together long enough for its conscience to overrule its economic appetites. The outcome would have pleased a good many of the Founding Fathers, who had postponed it only to get their great experiment off the ground in the first place. Or so we tell ourselves in the prevailing, ultimately Hegelian view that our history has been a long, diligent march toward enlightenment. Compelled by a core sense of justice, religious or secular, Americans always do the right thing in the end.

There is, as well, a less ennobling, more tragic reading of America’s founding. Slavery, it’s worth repeating, ended much earlier in parts of the Atlantic world. The landmark case of Somerset v. Stewart was tried before the King’s Bench in London in 1772. James Somerset was a black man whose putative master, Charles Stewart, had purchased him in Boston, then brought him back to London. Now desperate for funds, Stewart was determined to ship Somerset to the West Indies and sell him. When Somerset’s English godparents learned of the scheme, they sued on his behalf for his release. William Murray, Earl of Mansfield, ruled that no slave could forcibly be removed from Britain. Somerset walked out of the court a free man.

While the ruling opened the path to abolition in England and Wales, it sidestepped the question of the colonies. Nevertheless, it buoyed hopes for emancipation across the Atlantic — and inversely stoked apprehension among slaveholders. One might argue that the Southern colonies joined the American Revolution precisely to avoid the more enlightened laws of England, which they feared might soon prevent them from owning human chattel. In this view, independence was only a means to save slavery. The republic, in other words, was from the first a souls-for-silver deal with the devil. It is a reading that robs Americans of their sense of exceptionalism, and indeed consigns many of our most cherished myths to the trash. Are we an exemplary city on a hill? Or a civilization built on bondage, propelled by barbaric greed, vanity, and self-delusion? How you elect to read this past says a lot about your present vantage.1

Barack Obama is well versed in both outlooks. In his second book, The Audacity of Hope, there is an unabashed, wonkish love of the debates and ideas that led to the founding documents. He doesn’t know just the ratified Constitution — he knows the earlier drafts and the intervening arguments. After considering the noble-but-flawed and the congenitally damned views of American history, he judiciously punts:

How can I, an American with the blood of Africa coursing through my veins, choose sides in such a dispute? I can’t. I love America too much, am too invested in what this country has become, too committed to its institutions, its beauty, and even its ugliness, to focus entirely on the circumstances of its birth.

Dreams from My Father is the coming-of-age story and redemption tale (patterned, like many important American biographies, after the Pilgrim salvation narratives) of an exceptionally gifted, exquisitely thoughtful young man. The Audacity of Hope, written fast on the heels of his 2004 Senate victory, is the calling card of a politician mulling a run for higher office. It is a much more cautious document. Idealists are cautioned to consider the path carefully before acting, and the Great Emancipator is praised for his considered pragmatism: “Lincoln, and those buried at Gettysburg, remind us that we should pursue our own absolute truths only if we acknowledge that there may be a terrible price to pay.” This tactical vigilance presages exactly the poles he would be forced to navigate as a candidate.

There is well-established precedent for such caution. Just as the NAACP lawyers of the 1950s and 1960s were careful to build their landmark cases around the right plaintiff — say, a model citizen such as Rosa Parks, whom no one could deny unless they simply objected to her blackness — so, too, would Obama’s case have to be unimpeachable. He would have to be devoid of the character flaws and foibles allowed white candidates. He would have to embody both African-American and mainstream ideas of excellence: to show himself assimilated into the norms and codes that underlie the melting pot, but not so assimilated as to be deracinated, or worse, a sellout.

Even as Obama refrained from any “absolute truths” (which is to say, threatening views), the national media was quick to pounce on the question of where his racial sympathies really lay. As he rose in the polls, his authenticity as a black man was questioned: first within the African-American community, by such battle-weary leaders as Jesse Jackson, then before a wider public, by journalists like Stanley Crouch. The chorus was soon bolstered by old-line Democrats of both races whose bread and butter was the black vote, or at least paying lip service to the black perspective. When they asked whether Obama was black enough — an outrageous question never raised during his Senate campaign in Chicago — they might as well have been asking: black like who?

What these critics and self-appointed defenders of the color line were looking for was the mode of blackness shaped by a post-Panther assertion of pride and power. Other models, constructed before and since, didn’t strike them as legitimate. Indeed, the very question betrayed the interlocutor as a product of the blacker-than-thou Afrocentrism popular in the 1970s. If the King era of the civil-rights movement was molded by the politics of respectability (no one ever asked whether Thurgood Marshall was black enough), the post-assassination era brought forth the politics of indignation. To such detractors, Obama’s credentials and self-possession seemed not impressive but suspect.

And what of white scrutiny of the candidate’s blackness? It took two sadly predictable forms. There were those comfortable with Obama’s candidacy precisely because, unlike most of the old-school black politicians who came up under segregation, he adhered to establishment codes of power and the old politics of respectability. As Joe Biden blurted out in a moment of unwitting candor, “I mean, you got the first mainstream African American who is articulate and bright and clean and a nice-looking guy. I mean, that’s a storybook, man.” It was as if he had been kicked by a unicorn. Yet Biden spoke for most whites, who seemed never to have met such a black person.

In the African-American community, many took offense. Malcolm was handsome. Martin was well groomed. Both men could speak. Both were as smart as they come — even if Malcolm, fifty years after his death, still isn’t mainstream. If whites remained unmoved by King’s saintly patience and moral faith, and equally unmoved by Malcolm’s stunning intellectual honesty, prescience, and self-invention, what was left for the next generation but outrage?

Liberals also liked Obama precisely because he was assimilated in a manner that reflected well on current notions of multiculturalism. To embrace such a man affirmed the liberal establishment’s sense of its own progress. His challenge was to the color line, not to their own privilege. In a fair society, to be assimilated simply means being well adjusted. In one predicated on the dynamics of oppressor and oppressed, it is far more fraught.

There were, naturally, bred-in-the-bone racists who would never be comfortable with Obama’s candidacy simply because he was a black man. ABC News, in a gotcha moment, ran footage of Jeremiah Wright, Obama’s former pastor, attacking the notion of American benevolence. “God damn America!” he thundered from his South Side pulpit, in a clip that soon consumed headlines and internet chatter. The uproar that followed was fueled by a deep skepticism as to whether a black man could love America, and a deeper question about whether blacks are American. White discomfort, endlessly amplified by the media, had broken open wide.

Context, as always, was crucial — and, in this case, it was lacking. Few listened to the entirety of Wright’s sermon, which cited a litany of political rights the government had granted, sometimes grudgingly, to black Americans, before comparing the transient nature of social arrangements with the constancy of God. “Where governments change, God does not change.” Aside from the provocative sound bite, Wright’s sermon was an affirmation of faith for a flock whose dreams had been consistently deferred. No matter: as political optics, it was a disaster for the candidate.

Obama moved quickly to distance himself. The controversy, however, had outstripped the narrative, in a manner that Republicans genuflecting before race-baiting religious leaders seldom does. Whatever the nuance (or, for that matter, the substance) of Wright’s critique, his words now became a referendum on Obama’s entire campaign, just as Obama’s campaign had become a referendum on race in America. With his candidacy teetering, he was called on to defend himself — to quell white fears that he was somehow a Trojan horse for black militants. The American subconscious required proof that the junior senator from Illinois wasn’t John Brown with a law degree.

Obama moved quickly to distance himself. The controversy, however, had outstripped the narrative, in a manner that Republicans genuflecting before race-baiting religious leaders seldom does. Whatever the nuance (or, for that matter, the substance) of Wright’s critique, his words now became a referendum on Obama’s entire campaign, just as Obama’s campaign had become a referendum on race in America. With his candidacy teetering, he was called on to defend himself — to quell white fears that he was somehow a Trojan horse for black militants. The American subconscious required proof that the junior senator from Illinois wasn’t John Brown with a law degree.

Obama met the challenge in soaring fashion. As a student of political and racial history, he delivered a root synthesis of both, simultaneously telegraphing his authenticity as a black man and as a statesman. The capstone of his defense was his “More Perfect Union” speech, delivered in Philadelphia. This masterful performance went a long way toward reaffirming for both white and black Americans that he understood them, spoke their inner languages, and could unite one to the other, just as everyone hoped. As he had in The Audacity of Hope, he stressed the idea of American society as a flawed but potentially self-repairing entity:

The profound mistake of Reverend Wright’s sermons is not that he spoke about racism in our society. It’s that he spoke as if our society was static; as if no progress has been made; as if this country — a country that has made it possible for one of his own members to run for the highest office in the land and build a coalition of white and black, Latino and Asian, rich and poor, young and old — is still irrevocably bound to a tragic past.

Of course, we are bound to a tragic past. But the burden of the first black president, as he walked America’s racial tightrope, would be to help the nation transcend its politics and history. The mere fact of this speaks volumes about where we stand in relation to that past. To do so, Obama looked back not only at the Founders (citing the Constitution in his title) but at a more telling figure as well: Frederick Douglass. Stylistically and substantively, Obama’s speech echoed the oratory of this great predecessor — who, in an alternate version of history, ought to have been the first black president.2 In one of his most enduring speeches, “The Color Line,” Douglass, too, spoke equally to blacks and whites, articulating a vision of the future that has informed the most fruitful path toward equality ever since.

Douglass was among the few to recognize that the paper freedom granted by the Emancipation Proclamation was only the first step toward racial equality. He would spend the rest of his life championing civil rights, women’s suffrage, land reform, public education, and a panoply of other issues, ceaselessly arguing that America needed to be healed as a whole or not at all.

It is a healing that has yet to come. Douglass’s integrationist views — he argued that black America’s problems could be solved only within the context of the greater society — proved too radical for his day. This view has caused discomfort for many since the beginning. Even those like Jefferson, who knew integration to be the only just future, declined to imagine how such an arrangement could be implemented. It was too threatening to the white conception of self and to the material profits of colonialism.

Indeed, the task of integration has shown itself to be in many ways more difficult than abolition. We were nowhere near achieving an integrated society in 1895, when Douglass died. After him, the next great champion of a society made whole was W.E.B. Du Bois, the scholar, activist, and author, who would spend the final years of his life in self-imposed exile in newly independent Ghana. In the book that made his reputation, The Souls of Black Folk, Du Bois memorably described the problem of race as he saw it at the beginning of the twentieth century:

Indeed, the task of integration has shown itself to be in many ways more difficult than abolition. We were nowhere near achieving an integrated society in 1895, when Douglass died. After him, the next great champion of a society made whole was W.E.B. Du Bois, the scholar, activist, and author, who would spend the final years of his life in self-imposed exile in newly independent Ghana. In the book that made his reputation, The Souls of Black Folk, Du Bois memorably described the problem of race as he saw it at the beginning of the twentieth century:

One ever feels his two-ness — an American, a Negro; two souls, two thoughts, two unreconciled strivings; two warring ideals in one dark body, whose dogged strength alone keeps it from being torn asunder.

For Du Bois, steeped in Continental thought, psychic and societal integration were two halves of the same process. (Ironically, the “double consciousness” he posited as black America’s unique burden was meanwhile universalized — or appropriated, depending on where you sit on the bus — by the great modernists, until it came to be seen as the human condition itself.) In any case, this tradition of integrationist thought — the line that runs from Douglass to Du Bois to King and, despite the common view of him, to Malcolm — is where Obama springs from. Theirs are the hopes, the tools, and most certainly the problems that he inherited.

Who you know yourself to be, and what the world asserts that you are, has never been one and the same for minorities in this country.

In The Color Line (whose title and concerns encompass both Douglass and Du Bois), the historian John Hope Franklin weighs any single president’s power to change race relations:

It is too much to claim that the president of the United States, by his words and deeds, can unilaterally determine the course of history during his administration and countless subsequent years. It is not too much to assert, however, that the president of the United States, through his utterances and the policies he pursues, can greatly influence the national climate in which people live and work as well as their attitudes regarding the direction the social order should take.

Franklin wrote this passage in 1992, in the wake of Ronald Reagan’s presidency, and he cited Reagan’s regressive vision as proof of his thesis: from the start of his term, the president “began to contribute to the climate that tolerated racism and, indeed, encouraged policies and measures that denied equal opportunity and equal treatment.” Franklin, the St. Augustine of African-American history, tended to be evenhanded to a fault on questions of race. But by the end of his career, his thinking grew more pessimistic. A lifetime of studying the nation’s savage racial history had only convinced him that the intractable problem was nowhere near being solved: “I venture to state categorically that the problem of the twenty-first century will be the problem of the color line.”

By the time these words appeared in print, it was 1993. A wave of riots had swept through Los Angeles, incited by the acquittal of the police officers who had been captured on film one year earlier beating a helpless Rodney King. The beating fit right into the long history of state-sponsored violence against black citizens — a phenomenon many white Americans are still reluctant to accept. With greater urgency than ever, Franklin expressed his hope that in some indefinite future,

whites will discover that African Americans possess the same human qualities that other Americans possess, and African Americans will discover that white Americans are capable of the most sublime expressions of human conduct.

It was the same year that Obama, recently graduated from Harvard Law School, was writing Dreams from My Father. The crucial difference is that Obama takes these things as given, and is impatient with those who do not. His very self is evidence of the fact. The two men perceived American history and its racial dilemmas in similar terms, but they were separated by two generations. Where Franklin ends, Obama begins.

For many of us who came of age during this period, the racial dichotomies and absolutism of the preceding generations felt increasingly like relics of the past. The entrenched problems were the same as they ever were, and remain. But among the young, the Du Boisian notion of double consciousness was replaced by the sense of a vaster cultural inheritance, which belonged to all of us. If this was naïve, it was the naïveté of youth, which also produced the energy behind earlier civil-rights movements. Every generation wishes to believe its time is different. For the most part, it is not. But if we were not visited by this perennial hope, we would be powerless to make it so.

Unsurprisingly, younger people of all races moved swiftly to embrace Obama. Experience had prepared us for him. We had grown up in a society whose heroes — in art, sport, and culture — looked imperfectly but increasingly like the country itself. Where the first wave of modern integrationists were often self-consciously on display as black firsts, the succeeding generations had become much more confident of their right to belong. The public self and private self could exist in greater (if still not full) harmony.

Obama and his peers simply expected more: a fair shake, or the right, as King phrased it, to be judged by the content of their character. This was a positive development insofar as it put one on firmer psychological ground. It was negative to the degree that it left one more vulnerable to the intrusion of what is sometimes called the Negro Wake-Up Call. The moment when the bubble bursts and you notice how ugly things are. You can be president and they will still try to give you a different deal.

Whatever Obama’s own merits, the presidency is an inherently conservative institution, and bachelor politicians do not ascend. He had the extravagant fortune of meeting Michelle Robinson, a woman as poised and gifted as himself; one of the handful of political spouses who seem conspicuously capable of leading in their own right but who nonetheless submit to the antiquated expectations of the role. By her very presence, she lent him untold credibility.

Not only was her story more readily identifiable — she was, in Saul Bellow’s phrase, “an American, Chicago born” — but her rootedness, and her willingness to make light of her all-powerful husband’s tie collection, softened some of the perceived strangeness of his life.

For many, his history seemed to fit more readily into the narrative of British colonialism, with the Luo districts around Lake Victoria standing in for the Mississippi Delta. Yet this perception is largely due to willful ignorance of the world, and of the black experience in particular, and to our pernicious tendency to declare America exceptional. As is true of Kenya, South Africa, India, and any number of other countries, our economic inequality and stratified classes of citizenship are not arbitrary deviations from the rule of law but part of the original design. We are, however much we may protest the nomenclature, a postcolonial society. The real question when we talk about overcoming America’s racial legacy is whether any such society can be anything but history’s broken plaything.

If Obama was the exotic proof of our enlightened values, Michelle was the brilliant, beautiful striver next door. Many put their faith in her as much as in him. For their adversaries, meanwhile, both husband and wife were the quintessence of what used to be called uppity. The overt assaults against Michelle (and the shrill critique of her eleven-year-old daughter’s hair, to choose from a plethora of examples) spoke directly to the historic white fear of black revolt. The attacks on her husband were much more extreme, ranging from death threats to absurdist mythmaking. The most enduring example of the latter, of course, is the Birther movement, whose biggest champion, a man with no political experience, has now been elected president.

Although Donald Trump owes his rise to many factors, its cornerstone is simple enough to understand. As he called Mexicans rapists, threatened to ban Muslims from the country, and sang the praises of stop-and-frisk, he was reading chapter and verse from what Frederick Douglass called the “white book of libel.” The size and enthusiasm of his audience reflect the power these ancient lies continue to exert over the white psyche. As Douglass wrote, such prejudice is

Although Donald Trump owes his rise to many factors, its cornerstone is simple enough to understand. As he called Mexicans rapists, threatened to ban Muslims from the country, and sang the praises of stop-and-frisk, he was reading chapter and verse from what Frederick Douglass called the “white book of libel.” The size and enthusiasm of his audience reflect the power these ancient lies continue to exert over the white psyche. As Douglass wrote, such prejudice is

a moral disorder, which creates the conditions necessary to its own existence, and fortifies itself by refusing all contradiction. It paints a hateful picture according to its own diseased imagination, and distorts the features of the fancied original to suit the portrait. As those who believe in the visibility of ghosts can easily see them, so it is always easy to see repulsive qualities in those we despise and hate.

Douglass even anticipated Trump’s campaign slogan, declaring that the “superstition of former greatness serves to fill out the shriveled sides of a meaningless race-pride which holds over after its power has vanished.”

The rise of a nativist politician during this election cycle was not a fluke — given the long American love affair with racial hatred, it was nearly inevitable. Speaking to the legitimate grievances of the working class is still a perilous move in American politics: if done with any honesty, it usually brands the speaker a Marxist. (Bernie Sanders had enough trouble being labeled a socialist.) Speaking directly to racial anxieties, however, was Trump’s primary appeal to the electorate.

If we are ever to measure ourselves honestly on the state of race relations in America, it must be against Douglass’s original color line. We have made undeniable progress, but all the problems that bedeviled America during the Civil War era remain. They are relevant to our electoral map and to our life experience, and should serve as a barrier to any inflated sense of victory or self-congratulation. This is even more true now that the ghost of America’s colonial past has broken free of any attempts to control it. That ghost now sits in the White House, forcing us to reckon with it. The ghost is ugly and sinister and as native to this country as biscuits and gravy. We won’t be rid of it until our legal system, and economic system, and education system, and our individual nervous systems, are rid of it. This is what it would mean to move beyond the color line.

The morning I went to vote for the nation’s first African-American president, it was in the nearly all-white, overwhelmingly liberal Brooklyn neighborhood where I lived at the time. A palpable excitement rose to the rafters of the school gym that served as our polling place. My neighbors, for reasons having everything to do with the dynamics of gentrification, were people who had actively or passively avoided living side by side with those different from themselves. Indeed, New York, the city with the largest black population in the country, is also one of the most segregated. This is the color line in its most concrete form. It shows the distance between what people claim to believe (and there is no reason to doubt they believe it) and how they actually exist. If segregation continues to define where we live, go to school, work, and socialize in the most avowedly liberal city in the United States, how far can we really claim to have come?

Douglass saw the pervasive destruction, social as well as psychological, of this situation. He also saw how it protects and reproduces itself. “In presence of this spirit,” he wrote,

if a crime is committed, and the criminal is not positively known, a suspicious-looking colored man is sure to have been seen in the neighborhood. If an unarmed colored man is shot down and dies in his tracks, a jury, under the influence of this spirit, does not hesitate to find the murdered man the real criminal, and the murderer innocent.

No wonder Obama’s ratings dipped dramatically in 2012 when he pointed out that Trayvon Martin could have been his son — or indeed himself. He had struck too raw a nerve. He had asked Americans to change, to wrestle not only with the social arrangements that were glaringly wrong, but with those that served them just fine.

Obama’s victory would not have been possible without the victories of past generations. Yet it serves best the generation we will start to hear from during the coming decade, which grew up during his time in office and, one hopes, will take a greater sense of equality for granted. They will be a bit less infected by the sickness that came before. This was our true victory — affirming that as free people, we are slightly less ruled by the mistakes and misdeeds of history.

So long as the views of Strom Thurmond (who, it is worth noting, fathered a biracial daughter) have a place in the conservative mainstream, and so long as liberal belief is not matched by liberal behavior, the legacy of racism will continue to enslave a vast number of white minds and injure a great many black people. In the meantime, Obama’s legacy, which his Republican successor has promised to erase down to the very last executive order, seems assured. As one of the last black firsts, he bore their special burden, and he bore it with sterling integrity, self-knowledge, and extraordinary grace. He renewed the faith of many in the secular American belief that we are capable of overcoming any limitation, including the flaw of our founding.

However unknowable the future, it seems reasonable to think that Obama will ultimately be joined in the historical record with Lincoln, Douglass, Du Bois, Shabazz, King, and Marshall: beacons of the best path forward. It should be self-evident by now that this is the same path the deist Creator — the wellspring of our inalienable rights — always intended for us to follow.