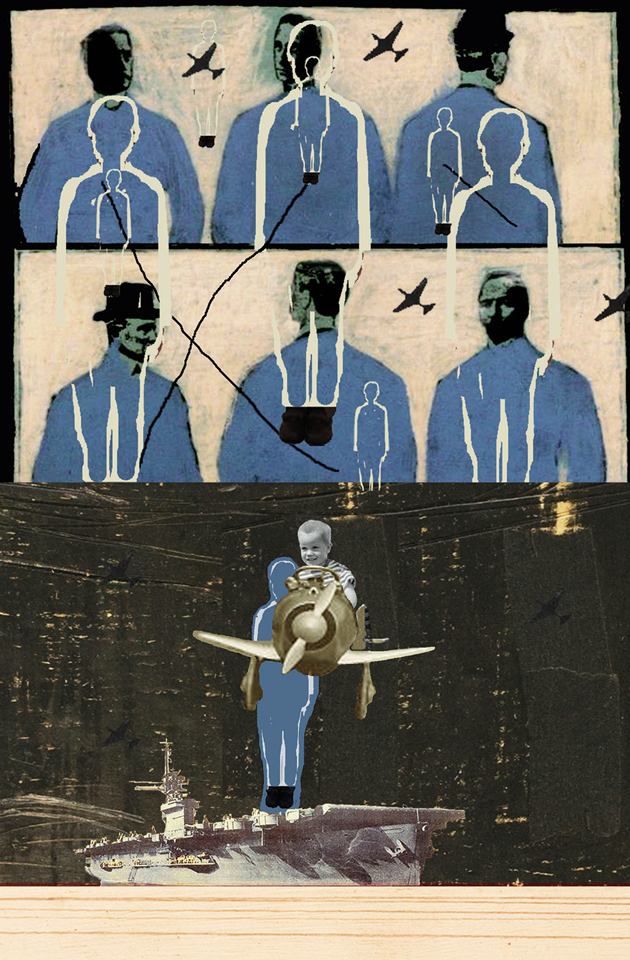

Fifteen years ago, in Lafayette, Louisiana, a little boy named James Leininger started having nightmares. Whenever his mother came to comfort him, she would find his body contorted, his arms and legs scrambling for purchase, as if he were struggling to extricate himself from something. The two-year-old repeated the same phrases over and over: “Airplane crash! Plane on fire! Little man can’t get out!”

Over the next few months, the dreams became more detailed. James told his parents that he had been a pilot. He’d been shot down by the Japanese. He’d been the little man who couldn’t get out. His parents asked where his plane had taken off from, and he said a boat called the Natoma. He talked about his friends on the ship: a man named Jack Larsen, along with Walter and Billy and Leon, the last three of whom had been waiting for him in heaven. James named his G.I. Joes after them. His parents asked what his name had been, and he said James, just like it was now.

The boy’s parents, Bruce and Andrea, started doing research. Andrea concluded that James was experiencing memories from a former life, while Bruce was determined to prove otherwise. But what Bruce discovered made his skepticism increasingly difficult to maintain. An aircraft carrier called the Natoma Bay had been deployed near Iwo Jima in 1945. Its crew included a pilot named Jack Larsen and another named James Huston, who was shot down near Chichi-Jima on March 3 of that year. The crew of the Natoma Bay also included Walter Devlin and Billie Peeler and Leon Conner, all of whom perished not long before Huston. How would a two-year-old have known the names of these men, let alone the sequence of their deaths?

Bruce went to a Natoma Bay reunion in 2002 and started asking questions. He told everyone that he was writing a book about the history of the ship; he didn’t tell anyone about his son — or what his son claimed to remember. He discovered that Jack Larsen was still alive. Andrea, meanwhile, was less worried about the military history than about ending her son’s nightmares, which kept troubling him for several years. She told James that his memories were real but that his old life was over; now he had to live this one.

This was the idea behind a trip the family took to Japan when James was eight years old. The plan was to hold a memorial service for James Huston. They took a fifteen-hour ferry ride from Tokyo to Chichi-Jima, then a smaller boat to the approximate spot in the Pacific where the American pilot’s plane had gone down. James tossed a beautiful bouquet of purple flowers into the ocean. “I salute you,” he said, “and I’ll never forget.” Then he sobbed for twenty minutes straight into his mother’s lap. “You leave it all here, buddy,” his father told him. “Just leave it all here.”

In the end, the Leiningers wouldn’t leave it all there — not at all. Three years after the trip to Japan, they published the best-selling Soul Survivor: The Reincarnation of a World War II Fighter Pilot (2009). They went on TV and were featured in numerous documentaries. Still, on that boat in the Pacific, something had been surrendered. When James finally looked up and brushed away his tears, he wanted to know where the flowers had gone. Could they see the blooms? They could. Someone pointed to a distant spot of color on the water: there they were, far off but still floating, still visible, drifting away on the surface of the sea.

We’ve all wondered — in some way, to some degree — what happens after we die. A 2013 Harris poll estimated that 24 percent of Americans believe in reincarnation, and 64 percent believe in the more loosely defined “survival of the soul after death.” We watch documentaries and TV specials like Round Trip: The Near-Death Experience and The Ghost Inside My Child, and buy enough copies of books like Heaven Is For Real to put them near the top of bestseller lists. But we’ve also become increasingly interested in something else: the fantasy of indisputable evidence, the possibility of finding — to cite another bestseller’s title — proof of heaven.

Jim Tucker, a child psychiatrist at the University of Virginia, is trying to approach the question with more academic rigor. He has spent the last fourteen years compiling a database as part of an effort to examine the past-life phenomenon. His research continues the work of his mentor, Ian Stevenson, who once chaired the UVA psychiatry department. Tucker’s database, which includes 2,078 cases, tracks children who have reported memories of prior lives. Over the years, certain patterns have emerged. Most of the children are between the ages of two and seven, and their memories, which sometimes take the form of vivid dreams, are suffused with a wide range of emotions, from fear to love to agonizing grief. The families of some subjects even insist that their birthmarks correspond to injuries sustained during past lives.

Tucker performs his research at the Division of Perceptual Studies (DOPS), a UVA research unit that studies near-death experiences, past-life memories, and extrasensory perception. DOPS was founded in 1967 and supported by a million-dollar bequest from Chester Carlson, the man who developed Xerox technology. To this day, DOPS receives almost no public funding — it’s financed by private donations — but many members of the UVA community still feel indignant about its connection to the university. A 2013 cover story about Tucker’s work in the UVA alumni magazine generated an avalanche of reactions: many readers were “appalled” by the research, while others were “appalled at those who were appalled.”

Tucker himself has something of a split institutional identity. In addition to assembling his database and interviewing subjects and their families, he also works as a supervising clinician at UVA’s School of Medicine. “My child-psychiatry work has been my mild-mannered Clark Kent identity,” he says. “But then there’s a secret identity, completely connected to another world.” It’s not secret at all, of course. Tucker’s work at DOPS is officially recognized and sanctioned by a major public research university. But straddling the two halves of his academic life can be “a tightrope,” Tucker says, and he concedes that there are sharply polarized reactions to his investigations of the paranormal.

My own sense of Tucker is that he’s a reasonable, articulate man, cautious in his phrasing because he knows how quickly his words might become fodder for tabloid spin-jobs or dismissive accounts of his research. Despite the sensational titles of his two books, Life Before Life: A Scientific Investigation of Children’s Memories of Previous Lives (2005) and Return to Life: Extraordinary Cases of Children Who Remember Past Lives (2013), both are careful to consider alternative explanations for the cases they describe. Yet Tucker believes that there is something extraordinary going on with these kids. He’s not sure he’s found any definitive answers yet, but he’s committed to keeping the question open.

In January 2014, I went with Tucker to visit a new case, near Richmond, Virginia. I wanted to see his approach in action: the kinds of questions he asks, the way he asks them, and what he does with the answers he gets.

Carol is a nineteen-year-old who, as a toddler, had inexplicable memories of a previous family: long-haired parents who grew herbs and owned a mint-green rotary phone. These memories dissipated long ago. But Carol’s mother, Julie, has been wondering about them ever since, and when she heard about Tucker’s research, she decided to get in touch.1

We meet mother and daughter in Mechanicsville, a suburb north of Richmond, in a small brick house down the road from a line of strip malls. The lawn is cluttered with deflated plastic Christmas decorations. A huge bony dog stands guard in the driveway. “I’m not going to encroach on that,” Tucker says, before parking across the street. (Inside, a reminder list posted on the fridge will tell us the dog’s name: feed optimus, let optimus outside.)

Julie does most of the talking. She tells us that Carol started speaking late and that she didn’t speak much once she started. Finally Julie asked her why she was so quiet. That’s when Carol first mentioned her other family: it confused her that she didn’t live with them. She missed them. “I felt like I had to tell her, ‘Yes, I really am your mother,’ ” Julie recalled. At the same time, she maintains that the specter of this past family never made her feel threatened or displaced.

She noticed that her daughter seemed drawn to things from a different era. As a girl, Carol liked retro fashion such as bell-bottoms, wanted a Sixties hairstyle like Florence Henderson’s on The Brady Bunch, and loved Seventies bands like Lynyrd Skynyrd. Tucker nods in response to all of this, taking notes.

Carol seemed to know all about rotary phones, Julie continues — sweeping an arc through the air with her finger to show the motion of dialing — even though she had never seen one in real life. And when she finally did see one, at a friend’s house, she cried out in recognition: “That’s what we had!”

At this point Carol finally interrupts to say, “Green, the phone was green.” This detail is important to her: she still sees the color with an eerie clarity. Yet she is also reluctant to make too much of these memories. “They could just be a dream,” she says. She seems a bit embarrassed by the whole thing, or bashful about recounting it with too much certainty. When Carol was growing up, Julie had always stressed that her past life wasn’t something to discuss at show-and-tell. Carol’s father, for example, was skeptical. (Julie describes her ex-husband as a guy whose life was pretty much just work, eat, sleep — no room for a past life in that kind of present-tense living.)

This conversation at the kitchen table, it seems, is the show-and-tell that never was. Julie now begins to explore another possible connection. Carol has recently started culinary school to learn to bake and decorate cakes for people with food allergies, and Julie speculates that her daughter’s creative tendencies may have also carried over from her prior existence: one of Carol’s strongest past-life memories is of drawing at a kitchen table.

The association feels charged with the willed electricity of a horoscope — take a life and a context, and we’ll find some connection between them. Indeed, Carol gently corrects her mother: this wasn’t the memory. She wasn’t drawing at a kitchen table but painting at an easel inside a glass-walled skyscraper. The conversation pauses. For a moment, we all dwell in the blurry zone between Carol’s memories and the stories Julie has told herself about Carol’s memories, where the kitchen has replaced the skyscraper and the kaleidoscope of memory has reshuffled its glimmering shards.

As we drive away, Tucker confesses that he’s not sure this is a particularly promising case. First of all, the memories are fifteen years old, and fairly vague — not specific enough to point toward a particular past life. Carol isn’t even sure the memories are memories. What made the biggest impression on Tucker, he says, was Julie’s reaction to her daughter’s hypothetical prior family. He saw a compelling instance of maternal love, but little usable evidence of possible reincarnation.

Tucker’s skepticism makes him more credible to me. So does his willingness to stay attuned to those subterranean channels of emotion running beneath the stories every family tells about itself. Still, I start to wonder about all those cases in his database: How many of them seem plausible to the investigator himself?

The DOPS offices occupy four suites in downtown Charlottesville, in a stately residential building called the Randolph. Bulletin boards sport inspiring quotes (“our notions of mind and matter must pass through many a phase as yet unimaginable”) as well as flyers describing ongoing research projects (“Investigation of Mediums Who Claim to Give Information About Deceased Persons,” “Mystical Experiences in Epilepsy”). A framed photo shows Bruce Greyson, the former director, handing a copy of a book he coedited, The Handbook of Near-Death Experiences, to the Dalai Lama.

Tucker points out the “shielded room,” designed for experiments on extrasensory perception. It’s a grim-looking cave with a La-Z-Boy recliner where a subject waits to receive messages from a “sender” elsewhere in the building. To block all forms of technological communication (i.e., to stop cheating), the walls are covered in metal sheeting.

Nearby we pass two spoons mounted on the wall; one looks as if it’s been melted over flames. I ask Tucker about them.

“Those?” he says. “Bent-spoon experiments.”

The library contains an impressive glass case holding weapons from all over the world — a Nigerian cutlass, a Thai dagger, a Sri Lankan sword — that are supposed to correspond to injuries “transferred” across lives. The placard beneath a gong mallet from Burma tells the story of a monk who was struck on the head by a deranged visitor, and allegedly came back a few years later as a boy with an unusually flattened skull. A nearby aisle has stacks of pamphlets and reprints documenting DOPS studies, including “Seven More Paranormal Experiences Associated with the Sinking of the Titanic.”

When a former director of DOPS died in 2007, he left behind a lock whose combination was known only to him. The idea was that he’d find a way to send it back if his soul survived death. (Tucker and his colleagues have received several call-in suggestions from strangers, but they haven’t gotten the lock open yet.)

I feel a kind of cognitive dissonance between Tucker’s self-presentation — his degrees, his clinical experience, his evident intelligence and courtly manner — and the more sensational trappings of his office. These incongruities make me curious about how Tucker got into this work in the first place. How did a traditional medical background deliver him to paranormal studies? He tells me he grew up Southern Baptist in North Carolina and never gave much thought to reincarnation until his second marriage, to a psychologist named Chris. She, too, was academically trained, but had a more inclusive spirituality than he did — she believed in psychic abilities and reincarnation. “Being with her opened me up,” he says, “to considering things I had never considered before.”

Tucker eventually grew to regard his child-psychiatry practice as “rewarding but not fulfilling.” It was gratifying, of course, to see kids getting better with treatment, but ultimately, he says, it was just “one appointment after another. There was no big picture. It was all small picture.”

For Tucker, his work with past-life memories is another matter entirely. He says that he’s not just providing care for individuals — he’s tracing the contours of a pattern so large that he can’t even see its edges. What he’s after now is the biggest picture, a picture that stretches beyond the limits of our vision.

In Return to Life, Tucker offers a speculative account of how quantum physics might explain a single consciousness persisting across a sequence of physical bodies. He cites famous findings — like the double-slit experiment, which suggests that light behaves differently when it’s observed — to argue that pure, disembodied consciousness can exert a force on matter itself. Tucker says his mother found this chapter a bit difficult to get through.

Several physicists I contacted declined to comment on Tucker’s theories; one expressed his skepticism in general terms. James Weatherall, a professor of logic and philosophy of science at the University of California, Irvine, conceded that Tucker has a capable grasp on the history of physics. Yet the book cherry-picks data, Weatherall told me, and misleads readers into thinking that “quantum physics leads inexorably to dualism, where consciousness is independent of matter and can cause matter to behave in certain ways. Even if we did accept this metaphysics, and even if we did believe quantum mechanics somehow forced us to it, I don’t see how we get to the idea that consciousness can be transferred from person to person. The physics doesn’t even hint at that.”

And how do psychiatrists view Tucker’s work? When I spoke to Alan Ravitz, then senior director of forensic psychiatry at the Child Mind Institute, in New York City, his response was less skeptical than I had expected. He admitted that Tucker had found “certain sorts of phenomena that are just difficult to explain,” and stressed that many of these reported past-life memories weren’t “the typical kind of imaginative material that kids would come up with.” To his mind, that left two possible explanations. Either we were in genuinely parapsychological territory, or “the children were exposed in some way or another to information, and then their response was reinforced.”

I asked how this process of reinforcement might work. “It doesn’t have to be an overt, egregious process,” Ravitz said. “It can be very subtle.” Even the fact of attention itself could be an engine of reinforcement. In Carol’s case, for example, her reports of a prior family had only deepened her mother’s protective and maternal impulses. Without any kind of scheme or design, Julie might have sustained these memories simply by paying attention to them.

As a specialist in forensic child psychiatry, including sexual-abuse allegations, Ravitz has seen the extent to which a child’s testimony can be influenced by context: how an interview is conducted, what kinds of questions are asked, how the nature and order and progression of these questions might shape the responses they elicit. If you ask leading questions, he said, children will typically tell you what you want to hear. “If you ask the same question three or four times,” he added, “eventually people will change what they tell you.”

This raises a few important caveats about Tucker’s work. Almost none of the information about these past-life memories comes from controlled interviews conducted primarily by Tucker himself. Instead, most of it has emerged from completely uncontrolled conversations between kids and their parents at home, which are subject to all sorts of influences that are impossible to retrospectively ascertain. This form of data collection is unlikely to change, for a simple reason that Tucker points out: in his view, it’s much more difficult for children to talk about these kinds of memories with a stranger.

The opportunities for parental evidence-tampering are thick on the ground — there’s no getting around that. Yet Tucker is dubious about deliberate fraud as an explanation for what’s happening with these families. Why would they fabricate outlandish stories that might earn them little more than ridicule? More likely, it seems to me, is a process of unwitting reinforcement, a kind of unintentional narrative collaboration: This is why Carol was shy. Stories about past lives help explain this life — they promise a root structure beneath the inexplicable soil of what we see and live and know, what we offer one another.

Of course, Tucker would never point to Carol as a particularly strong case. After the interview, he told me that he probably wouldn’t even add her to his growing arsenal of evidence. But not many of the other cases in Tucker’s database seem particularly strong either. Of his 2,078 cases, nearly two thirds have been “solved,” a term Tucker uses to indicate that a possible previous life has been identified, even if nothing has been proven. In the majority of these cases, the candidate is someone associated with the child’s family: only 324 are what Tucker calls “stranger cases.”

For obvious reasons, these stranger cases are more unsettling. But they constitute a tiny fraction of the total number, especially in America. As it happens, only 142 of Tucker’s cases are non-indigenous American; the bulk of them are either foreign or from Native American tribes.2

What to make of how these numbers break down? First of all, it’s worth noting that the cases that show up in Tucker’s two books aren’t representative of his database. He’s open about this, saying that he chooses to highlight the most compelling cases (what he calls his “greatest hits”) in order to challenge the skepticism of his readers. This makes sense, because the composition of his entire database is precisely what makes me skeptical. If we restrict ourselves to American stranger cases that have been solved the database shrinks from a robust 2,078 to a more modest number: three. These include James Leininger, the Louisiana boy who remembered being a pilot, and Ryan Hammons, a boy in Oklahoma who had memories of a life in old-time Hollywood.

As Tucker says, these two cases “are quite unusual for the American ones, essentially unique at this point.” He describes the Leininger case as “a tipping point” for him because it was so difficult to explain by any other means. This is exactly what I need: the thing most difficult to explain by any other means. As Ravitz says: “Who the hell knows? Anything is possible.” So I fly to Louisiana.

At the Leiningers’ home in suburban Lafayette, the front yard is shadowed by river birches draped in Spanish moss, and the dining room table is covered with notebooks and folders. These contain more than a decade’s research into the history of the Natoma Bay and its pilots. Bruce has pulled out his materials for me to see — “only a fraction,” he says, of what he has in his closets.

He has compiled a separate notebook for every single soldier who died on the ship, crammed with as much biographical information and as many military after-action reports as he could assemble. There’s a wooden champagne crate full of microfiche reels that the ship’s historian sent him. Everything is labeled property of bruce leininger / research material for ‘one lucky ship’ ©.

One Lucky Ship is the book that Bruce is writing about the Natoma Bay, the book that will finally make good on the story he told veterans in order to gain access to their inner circle. Now deeply immersed in this second book, Bruce tells me a bit about writing the first one. He is proud to say that Ken Gross, the prolific ghostwriter who helped him and Andrea with Soul Survivor, was a skeptic before he took on the project. Gross confirms this over the phone, and says that he still doesn’t believe in reincarnation, but also finds James’s story fundamentally inexplicable. “The good question to ask me is if I’m looking for resolution,” he says. “The answer is no.” For Gross, the moral of this story is that there is no moral — nothing resembling what he calls an “ultimate syllogism.”

The Leiningers, however, do find a moral in all this. They believe that James Huston returned in the body of their son for a reason. Bruce believes it happened so that he and Andrea could recover this sliver of American history, one that might otherwise have been lost. The Leiningers took it upon themselves to send the families of the dead pilots whatever information they gathered about how their loved ones had fought and died — specifics many of the families had never gotten from the military.

Bruce and Andrea managed to locate Anne Huston Barron, James Huston’s sister, whom they initially befriended under the auspices of their usual cover story. About six months after making contact, however, they decided to tell her the actual reason for their interest in her brother. They were nervous. What if she thought they were crazy? They called and told her she might want to pour herself a glass of wine. They had the number of her local E.M.T. service on hand in case the news was too much of a shock.

As Bruce and Andrea describe these things — the glass of wine, the E.M.T. number — I hear echoes of Soul Survivor. All these details have become part of a well-worn story. Even its grooves of self-deprecation hold the uneasy echoes of lines performed effectively and often.

But should their story’s burnished texture necessarily arouse our suspicions? This is how stories work, inevitably, and this is how we live by them: things happen, we make sense of them, our sense-making becomes (inevitably, over time) a performance of its own. The feeling I get from the Leiningers is that beneath the veneer of their well-told story is the kernel of a mystery that came upon them unbidden — not a narrative they controlled but something they struggled to make sense of.

As for Anne? She wasn’t sure what to make of their revelation at first — she was shocked — but eventually she embraced the idea that their son was her brother reincarnated. Bruce shows me one of her letters: “All of this is still overwhelming,” she writes. “One reads about it, but never expects it to happen to you.” And in her neat, orderly print, an unequivocal affirmation: “But I believe.”

While Andrea has always been fixated on James (how to make his nightmares go away, whether Huston’s battle injuries explain any of her son’s health problems as a baby), Bruce’s relationship to the history of the Natoma Bay has taken on a life of its own. “It’s hard to say who’s more dogged,” Gross observes. But their respective forms of doggedness diverge. While Andrea wants to show me James’s drawings, Bruce wants to show me notebooks full of distant battles.

Andrea’s story has a narrative arc — a beginning, a middle, and an end — while Bruce sees something more infinite: a story with no possible ending. As he freely admits, “I was obsessed.” It seems the obsession has continued.

Bruce takes me to the office closet that James once pretended was his cockpit: the boy would jump out wearing a canvas shopping bag on his back like a parachute. Then Bruce brings out some of the artifacts he’s gathered over the years, including a vial of soil from Iwo Jima and a piece of melted engine from the kamikaze plane that flew into the Natoma Bay in 1945, the metal hunk coated in melted tar and bits of redwood from the ship’s deck. As Gross points out, these items are not so far removed from the Christian tradition of holy relics — and indeed, there is a strong sense of the sacred in the way Bruce approaches this story. He describes the Natoma Bay veterans as his “Knights of the Round Table.”

It might be easy to deem the Leiningers little more than hucksters of petty mystery, parents who have turned their son’s alleged past life into something like a cottage industry: a best-selling memoir and another book in the works, a slew of television specials and speaking gigs. But it’s clear that James’s experiences have become an enduring engine for them, a source of purpose and vocation. And telling the story of something extraordinary and painful and confusing — even selling that story, and wanting it to be heard — doesn’t invalidate the experience itself, nor the mysterious nature of its origins: the ferocity and persistence and specificity of James’s nightmares, a toddler somehow haunted by the details of a war he never saw.

As for James himself, he strikes me as a pretty well-adjusted teenager. Over dinner, in the shadow of a twelve-foot stuffed alligator, he explains why he prefers jujitsu to karate, and gives me a brief primer on how I can tell whether my gator meat’s been decently prepared. These days, he wants to be a Marine, instead of a Navy fighter pilot like James Huston. He spends much of the afternoon playing a video game that involves shooting from a simulated cockpit, and his bedroom is still full of model airplanes dangling from the ceiling, many of which Bruce built for him.

Andrea finally gets to show me a stack of James’s drawings: the messy circles he drew to show the motion of propellers, the dots meant to represent anti-aircraft flak, everything broken and splintered and covered with messy rashes of fire. She shows me stick-figure parachutists falling through the sky — some with chutes open above their bodies, and other ones, less lucky, whose chutes have collapsed into straight lines above them. From across the table, Bruce mentions that according to an after-action report he found, James Huston once shot down a parachuting Japanese pilot. Andrea is shocked; she hadn’t known that.

“I just got chills,” she says. “That’s probably why James was always drawing them, because he shot one down.”

The Leiningers offer to show me a few of the television specials they’ve been featured in. We watch The Ghost Inside My Child. We watch Science of the Soul. At this point, these television specials haven’t just documented their experience but constituted their experience: for almost the entirety of their son’s life, Bruce and Andrea have shared him (and themselves) with a public audience.

The family on the flatscreen enacts a strange simultaneity: sincerity and performance at once. Often when we sense the latter, we immediately discount the former. But the story of the Leiningers is the story of both — genuine experience morphing into public spectacle — and that duality is only amplified when I sit beside them on their couch, watching them on television.

We watch a Japanese special with a voice-over that has never been translated; the Leiningers still don’t know what it says. It was this special that funded their cathartic trip to Chichi-Jima and made possible the farewell that Andrea believes liberated James from his memories. We watch the B-roll footage: the Leiningers sitting on a boat, passing the hours, waiting for the ritual. I’ll get to see James weeping, they’ve told me, and it almost feels like a promise, or a challenge: Try not to believe after you’ve seen how he cried.

It doesn’t surprise me that Andrea leaves, insisting that she needs to buy a printer cartridge. She says it makes her too emotional to watch how James cried. So Bruce and I watch without her. He wants to skip his “silly speech” on the boat and I ask him not to. It turns out to be an earnest homage to the bravery of James Huston, and alludes to the beauty of his final resting place, these blue waters off a remote Japanese island, which is also — Bruce says — “where my own son’s journey began.” People in the film keep asking James how he’s feeling. “Okay,” he says. “Good.”

I can’t help wondering whether James’s initial responses were disappointing to his family, or to the filmmakers: an elaborate memorial staged on the other side of the world, and no tears to show for it. Onscreen, however, Bruce gives no sign of disappointment. “I’m glad you don’t feel anything,” he tells his son. “You’ve suffered for so long.”

But when Andrea finally says that it’s time to say goodbye to James Huston — after the eulogy is done, tribute paid — that’s when her son starts crying. And then he keeps going. He just can’t stop.

Offscreen, on his living room couch, Bruce gets quiet. He says that it still upsets him to consider what was going through his son’s head that day. At one point a camera guy creeps into the frame to give James a hug. Then he embraces Bruce too. “They were just in pieces,” Bruce says, meaning the whole crew. I wonder what it must have been like for them, sitting beside the ostensible reincarnation of a soldier who fought against their country.

Andrea rejoins us later to watch some of the other documentaries. She says she especially likes the one that doesn’t make her look a million years old. The friendliest of the family’s four cats joins us on the couch but turns away from the screen: I sense that she, too, has seen these shows before. Bruce mouths the words he’ll say onscreen before he actually says them. “Bullshit!” he whispers to himself, a moment before he barks out the word onscreen, where he is trying to re-create his own skepticism for the interviewer behind the camera.

For her part, Andrea is keen on my seeing James’s account of all this. While we’re still seated in front of the television, she hands me a piece of writing he did in seventh grade called “Nightmares”:

The burning torture of fire and smoke hit me every single night for five years. . . . The nightmares were not dreams, but something that actually happened: the death of James M. Huston. His soul was brought back in the human form. He was brought back in my body and he chose to come back to Earth for a reason; to tell people that life is truly everlasting.

The specter of skepticism haunts the crescendo, and James is wise to it:

You can think I am a fool for knowing this, for believing these things. But when my parents wrote the book about me and my story, people who were deathly ill or had incurable diseases sent me e-mails that said, “Your story helped me and made me not afraid to die.”

Meanwhile, on TV, Bruce sits on a tiny boat and places a hand on his son’s back. “You’re such a brave soul and spirit,” he says.

I wonder at the many forms a parent’s care can take, the many languages in which it can announce itself: love filling the gap between everything known and everything else, between the hours of bedtime and dawn, between what we can’t explain and the explanations we seek anyway.

Did I leave Louisiana thinking James Leininger was a reincarnated fighter pilot? No. The case may have been Tucker’s tipping point and greatest hit, but in the end it suggested a set of narrative hydraulics similar to the rest: a few details had seeded a much more elaborate tale, which promised to make sense of what was troubling the child. Even Bruce Leininger’s insistence on his former skepticism wasn’t something that ran counter to his faith — it was a necessary part of the same narrative arc, suggesting to other skeptics that their doubt was perfectly reasonable but ultimately wrong.3

Did I leave feeling that the Leiningers were sincere in their beliefs about reincarnation? Absolutely. I was surprised at the way that Tucker kept disputing charges of deliberate fraud, which seemed like an easy straw man. Something more complicated was going on with the Leiningers — and something simpler. It seemed to me that they were just a family seeking meaning in their experience, as we all do. In this case, the human hunger for narrative — a hunger I experience constantly, and from which I make my living — had built an intricate and self-sustaining story, all of it anchored by the desire to care for a little boy in the dark.

Maybe there’s no universal syllogism. Maybe, instead, there’s an imperative: whenever a child is crying out, we shouldn’t just listen, we should consider the ways our listening might change the story we’re hearing. But we should also keep listening, even after comprehension fails and we’re left with pieces we can’t fit together, the parts of a machine whose blueprints are missing, whose function we don’t know. You can think I am a fool for knowing this. We can still appreciate the wild mechanisms of the human mind and heart. At the bottom of James’s composition his teacher wrote just one word, three times in red: Wow. Wow. Wow.