For 173 years, the Stoneman House stood peacefully in the Tuscarawas Valley on the outskirts of Leesville, Ohio. The elegant two-story brick structure was owned and occupied by just three families over successive generations, and when the last of them died, in 2015, it was bought by Energy Transfer Partners, a Texas pipeline company, which promised there would be “no adverse effects” on the historic site. The following year, ETP razed the house to the ground, causing Goldman Sachs to lose $100 million.

The doomed mansion was located close to the projected path of the Rover Pipeline, which was being built to carry natural gas from the Marcellus Shale in Ohio, Pennsylvania, and West Virginia to Canada. Once the $4 billion project was completed, Goldman traders had calculated, the price of Marcellus gas would rise. They placed their bet accordingly. Their wager depended on the pipeline proceeding according to schedule. But the brazen destruction of the beloved mansion, which had been eligible for inclusion in the National Register of Historic Places, enraged national and state regulators, who were further dismayed by toxic spills in protected wetlands and other environmental depredations. Rover was temporarily stopped in its tracks in May 2017. Instead of rising, Marcellus gas prices plummeted—and Goldman lost its bet.

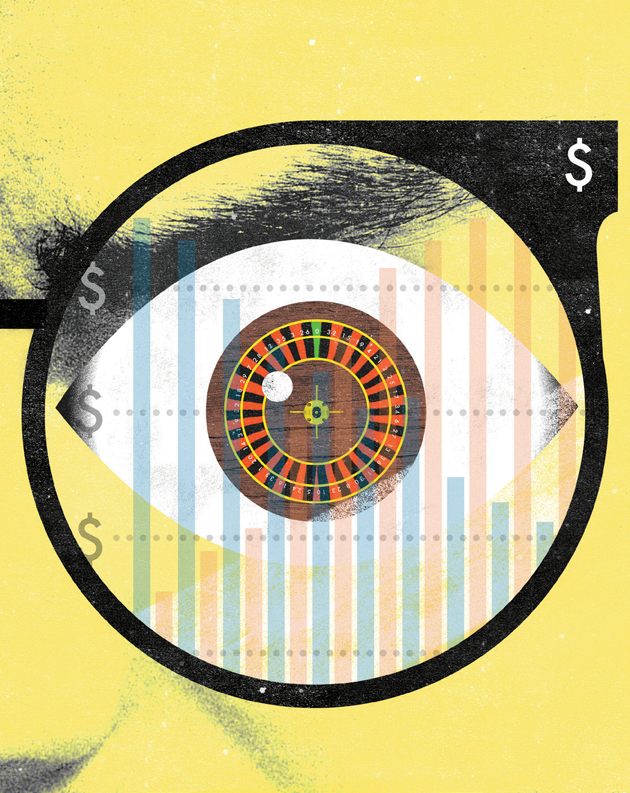

Such wagers were meant to be a thing of the past. A decade ago, Wall Street was a roaring casino and a trader could toss away $9 billion on a single bet. The financial crisis that followed in 2008 generated a forest of new regulations, most of them incomprehensible to the average observer, not to mention the legislators who voted for them. But there was one reform that seemed simple to understand. It was named for the man who conceived it: Paul Volcker, the venerated former chairman of the Federal Reserve.

In the early days of the crisis, as the collapsing industry ran to the federal government for bailouts, Volcker proposed that commercial banks should be forever barred from proprietary trading (referred to on Wall Street as prop trading)—meaning speculative bets with their own capital. Nor should such institutions be permitted to bankroll hedge funds or other inherently risky ventures. His aim, Volcker told me recently in a phone call from his office in Midtown Manhattan, was to change the “whole psychology” of the banking system. Is the primary function of banks to “make loans and serve the banking needs of their clients,” he asked, or are they “preoccupied with going off and making money with proprietary trades, which will often conflict with their customers’ interests? That’s the issue involved here. They all talk about how the client comes first. They’ll say, ‘All our remuneration, all our everything, is directed toward the client.’ That can’t be true when you’re doing proprietary trading.”

Once he touched on the subject of prop trading, I brought up Goldman Sachs. “They want to trade everything, for God’s sake!” cried the sharp-tongued nonagenarian, cutting me off. “They’ll trade the office rug that I’m looking at.”

As we spoke, Goldman, its second-quarter trading profits down (in part because of the losing Marcellus bet), was leading an industry charge to make the Volcker Rule go away—not by getting it repealed in Congress but by adjusting the rules and regulations through which it has been enforced.1 They were certainly assured of a sympathetic hearing from the Trump appointees now ensconced in the regulatory agencies, notably Keith Noreika, a corporate lawyer and frequent advocate for the banking industry who currently serves as acting comptroller of the currency, the chief regulator of the banks. Meanwhile, the US Treasury, headed by the former foreclosure profiteer Steven Mnuchin, announced plans in June for “improving” the Volcker Rule, which the department chided for having “far overshot the mark.” Duly encouraged, banking groups and their lobbyists argued that the rule’s complexity imposed unbearable burdens on bankers and had dried up liquidity, meaning that banks lacked sufficient funds to lend to deserving businesses.

I cited some of the lobbyists’ complaints to Volcker. “They’re paid to do that,” he replied scornfully. “All I know is that people stop me on the street. Some of them are bankers, who say, ‘Thank God for the Volcker Rule. It has changed the psychology of the trading operation in the bank.’ I don’t know how many of these people are just being nice to me, but I don’t get many coming up to me and saying, ‘It’s a terrible rule.’?”

The Volcker Rule was born of political expediency. Despite his towering prestige as the man who stamped out the rampant inflation of the early 1980s, Volcker and his plan were studiously ignored by President Obama and his advisers until early in 2010. At that point, it dawned on the administration that the American people were outraged at the way the banks had crashed the economy and then been bailed out. Furthermore, popular anger was taking a dangerous turn, signaled by the election of Scott Brown, a former Cosmo nude model running on an antiestablishment platform, as a Republican senator in Massachusetts, presaging the rise of the Tea Party. Two days after Brown’s victory, Obama summoned Volcker to the White House and announced his support for the Volcker Rule as a key component of financial reform.

Sponsoring enactment of the rule in the Senate were Carl Levin of Michigan and Jeff Merkley of Oregon, both of them Democrats. Levin, a veteran lawmaker, had a clear-eyed understanding of the way the banks operated. Merkley was a freshman senator, spurred, as he told me recently, by having “seen firsthand the impact of predatory mortgages” on his constituents back in Portland. Now he had the chance to do something about the system that was generating those loans: prop trading. There was no logic, he told me, in having a bank “that is designed to take deposits and make loans be placing high-risk bets in a Wall Street casino.”

By 2010, the crash in the housing market was tearing communities apart across the country, as millions of people faced foreclosure and eviction. Yet these hapless borrowers had already generated vast profits for others. Unbeknownst to most of them, their mortgages had been “securitized”—that is, welded together by financial engineers into investment “products,” which were, in turn, sold to other buyers. It was rarely possible to track an individual subprime mortgage through the financial Cuisinart in which Wall Street transformed such loans into profitable instruments. Thus the eventual buyers had no idea whether the underlying mortgages were being paid or not.

I was, however, able to follow one such mortgage: a loan to Denzel Mitchell, a young African-American high-school teacher, which passed through successive hands until Goldman Sachs blended it, along with 3,061 others, into a $629 million bond called GSAMP 2006 HE–2 (Goldman Sachs Alternative Mortgage Product Home Equity–2). In those years before the crash, Goldman was doing a roaring trade in GSAMPs, selling them to credulous institutions, many of them foreign, that were either oblivious or indifferent to the fact that the underlying loans were almost certain to default. Such prop trades brought in a river of cash for Goldman—more than $25 billion in net revenue in 2006—with commensurate payoffs for the traders who generated them. That year alone, Gary Cohn, who oversaw Goldman’s trading division, garnered $53 million in total pay. The following year, he took home $70 million. Today, he is Donald Trump’s chief economic adviser.

But there was more to it than that. Back in 2005, at the peak of the subprime boom, Wall Street traders had dreamed up the ABX index. By tracking a selected sample of mortgage-backed housing bonds, the index would reflect the mortgage-backed securities market as a whole, and by extension, the American housing market. Launched in January 2006, the ABX also offered the attractive option of buying and selling index futures. That is, traders could now place bets on the movement of the entire housing market.

Goldman was quicker than most to place negative bets, predicting that the housing market would tumble as more and more homeowners defaulted. So, as Denzel Mitchell struggled to keep a roof over his family, the bank that owned his loan was betting that he and others would fail. That turned out to be a very good bet, generating nearly $4 billion in profits in 2007 alone.

Goldman was by no means the only establishment to use the ABX. Among the others were a small number of traders in the London branch of JPMorgan Chase’s Chief Investment Office, a division of the bank charged with investing customers’ deposits. These particular London traders oversaw what the bank management termed the synthetic credit portfolio, largely composed of exotic derivatives.

The activities of the group, which included a Frenchman named Bruno Iksil, were kept secret from the bank’s government regulator. According to a subsequent explanation by Jamie Dimon, JPMorgan’s CEO, the purpose of the SCP was to make “a little money” when the overall market was doing well—and to make a lot more in the event of a crash.

Such transactions were cascading through the global financial system in those years, powered by the bank-promoted boom in subprime loans. Vastly magnifying the scale of operations was another recently invented instrument: the credit default swap. These enabled traders to take out insurance, or “protection,” as they preferred to call it (labeling it “insurance” would subject the deals to insurance regulations), on bonds they didn’t own—just like insuring someone else’s house against fire. There was no limit on the number of bets riding on a particular bond; a post-crash inquiry found one that had nine separate CDS bets against it. Thus, if a $600 million GSAMP collapsed because its loans were worthless, those on the wrong side of the bets stood to lose multiples of that sum: the single most important reason why the subprime crash almost dragged the entire economy down with it.

Such transactions were cascading through the global financial system in those years, powered by the bank-promoted boom in subprime loans. Vastly magnifying the scale of operations was another recently invented instrument: the credit default swap. These enabled traders to take out insurance, or “protection,” as they preferred to call it (labeling it “insurance” would subject the deals to insurance regulations), on bonds they didn’t own—just like insuring someone else’s house against fire. There was no limit on the number of bets riding on a particular bond; a post-crash inquiry found one that had nine separate CDS bets against it. Thus, if a $600 million GSAMP collapsed because its loans were worthless, those on the wrong side of the bets stood to lose multiples of that sum: the single most important reason why the subprime crash almost dragged the entire economy down with it.

By 2007, the bets were going bad at an ever-accelerating rate. In October, Howie Hubler, a senior trader at Morgan Stanley, managed to lose more than $9 billion on a credit default swap bet—the single largest trading loss in Wall Street history. Huge financial institutions began to crumble. Bear Stearns collapsed in March 2008. On September 15 came the cataclysm of the Lehman Brothers bankruptcy. An internal Federal Reserve email sent five days later, and published here for the first time, tersely conveys the prevailing mood of official panic as Morgan Stanley, Timothy Geithner, and Goldman Sachs attempted to circle the wagons:

FYI, MS called TFG late last nite and indicated they can not open Monday. MS advised GS of that and GS is now panicked b/c feel that if MS does not open then GS is toast.

Washington rushed to shore up the collapsing financial system. AIG, the giant insurance company that had thoughtlessly taken the other side on a huge proportion of the banks’ CDS bets, was bailed out with $185 billion of taxpayer money. By March 2009, the Treasury and the Federal Reserve had committed $12.8 trillion—almost as much as the entire US gross national product—to save the economy. Fearful of public outrage over such generosity to those who had fomented the disaster in the first place, the Fed and the banks struggled to keep the numbers a secret.

Fortunately for the bankers, they had protection from the top. In March 2009, President Obama reportedly assured a roomful of bank CEOs that his administration was “the only thing” standing between them “and the pitchforks.” He would neither allow them to fail nor send any of their top administrators to jail for fraud (although the banks would subsequently disgorge billions in civil fines for their fraudulent behavior).

Despite such welcome news, the banks did face the unwelcome prospect of new rules and regulations likely to impinge on cherished modes of operation. They prepared their defenses. By November 13, 2008, just a month after being raised from the dead by the government’s largesse, the biggest derivatives dealers—including JPMorgan, Goldman Sachs, Citigroup, and Bank of America—were already investing $25 million in setting up the CDS Dealers Consortium, a lobbying group aimed at preserving their freedom to trade credit default swaps without irksome restrictions.

Volcker’s rule represented a partial resurrection of the Glass–Steagall Act, the Depression-era law that had separated commercial banks from investment banks, effectively banning prop trading. (It was repealed by a stroke of Bill Clinton’s pen back in 1999.) As noted, the former Fed chairman’s idea found little support in an administration predisposed, as Treasury Secretary Geithner infamously put it, to “foam the runway” for the banks.

The Volcker Rule was even more anathema to the banks themselves, which, flush with bailout cash, were once again generating profitable trades and executive bonuses. At the end of 2009, Goldman handed employees nearly $17 billion in pay and bonuses. In London, the traders in JPMorgan’s SCP unit generated $1 billion in revenue, thanks largely to a shrewd bet that General Motors would go bankrupt. Bankers and their representatives argued vehemently that their prop trading had absolutely nothing to do with the crash, despite the trillions in bailout money needed to keep them afloat.

The Volcker Rule meanwhile had to undergo a long and tortuous gestation, beginning with its passage through Congress as part of the financial reform legislation introduced by Senator Chris Dodd and Representative Barney Frank. On hand to observe the progress of the legislation was Jeff Connaughton, formerly a high-powered lobbyist, who had recently signed on as chief of staff to the reform-minded senator Ted Kaufman, a Democrat from Delaware. In his instructive memoir The Payoff, Connaughton describes how the banking committee functioned:

Staffers gave lobbyists information about bills being drafted or what one senator had said to another.?.?.?. The lobbyists passed the information on to their clients in the banking or insurance or accounting industry.?.?.?. Sometimes within an hour, the news would be emailed to the entire financial-services industry and all of its lobbyists. With multiple leakers from the banking committee keeping K Street well informed, the banking world had complete transparency into bill drafting.

Among the lobbyists’ prime sources, according to Connaughton, was Dodd himself, who spent hours hashing out the bill with them behind closed doors. (“I remember when I told Jeff that I’d just spent forty-five minutes discussing the bill with Dodd,” one lobbyist told me recently, laughing at the memory. “Jeff was so upset!”)

As veterans of the committees they now monitored, many of these financial lobbyists had inside knowledge. Michael Paese, for example, was the deputy staff director of the House Financial Services Committee for seven years until moving to the Securities Industry and Financial Markets Association, a trade group, in September 2008. He left with committee chairman Barney Frank’s blessing, so Frank told me, after assuring him that he was joining SIFMA in hopes of converting the group to the benefits of regulation. When Paese then joined Goldman Sachs in April 2009 as its chief lobbyist, Frank, furious that his former aide would now be working “for the people who were likely to try to undermine the bill,” banned him from contacting the committee for two years.

The lobbyists saw little point in exercising their skills on Carl Levin, a seasoned politician whose views on the banks were well known. “They knew my boss was probably not going to be taking advice from Goldman about the Volcker Rule,” Tyler Gellasch, Levin’s staffer on the issue at the time, told me. “He was busy investigating them for fraud, and they were smart enough to realize that.”

But the industry emissaries could always find more pliable senators to convey the message. Ironically, Scott Brown, whose election had prompted the White House to endorse Volcker’s initiative in the first place, became “a bit of a poster child” for such horse trading, Gellasch recalled. “He was perceived to be one of the swing votes. The staffers basically used that as leverage: ‘We’re a swing vote on Dodd–Frank. You’re going to give as many things as we can ask for.’?” Some Senate staffers joked about setting up an ATM machine for campaign contributions out in Senator Brown’s lobby. Among other concessions extracted by the Massachusetts senator was a loophole in the Volcker Rule allowing banks to own a small stake in hedge funds after all. (Coincidentally or not, the securities and investment industry was Brown’s most generous contributor during his single Senate term, donating more than $4.6 million, while his legislative director, Nat Hoopes, went on to run the Financial Services Forum, another well-endowed lobbying group.)

Thanks to such negotiations, the rule acquired significant concessions before Dodd–Frank was passed on July 21, 2010. Connaughton, whose boss’s proposal to break up the big banks had gotten short shrift from the administration and Congress, thought little of the final result. “Dodd and the Treasury wanted a squishy bill, and the Republicans were willing to work with him to weaken it,” he told me disgustedly. “Dodd–Frank wasn’t really a law but a series of instructions to regulators to write rules.” To start with the basics: What did “proprietary trading” actually mean? If you kept a supply of, for example, foreign-currency swaps in stock, just in case a customer ordered some, were you engaging in prop trading? Such issues could keep many lawyers well remunerated for a long time.

The banks pressed to be allowed to carry a much bigger inventory of any given product—which Dennis Kelleher of Better Markets, a financial watchdog group, described as “just a disguised form of prop trading.” They also saw a potential loophole in even the most straightforward language. “Normal people in the real world would understand those things quite easily,” Kelleher told me. “But when you get together all the lawyers, lobbyists, traders, and bonus-salivating bankers, it’s as if those words were being spoken in a foreign language, given the amount of questions and ambiguities that they can see in them.”

The regulators overseeing implementation of the Volcker Rule were from five separate agencies. These included the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency (OCC) and the Commodity Futures Trading Commission (CFTC), obscure to the public but potent acronyms in the financial world. Though immediately touted as a signal achievement by Obama and the Democrats, the Volcker Rule would be toothless unless and until these agencies spelled out what it actually meant.

Unsurprisingly, the banks and similarly interested parties launched waves of lawyers and lobbyists at the agencies to ensure that rules were crafted to their liking. A painstaking academic study of the public record by Kimberly Krawiec of Duke University revealed that the agencies were subjected to almost 1,400 meetings with those seeking to influence their deliberations, the vast majority with representatives of the financial industry.

Though the rule sprouted increasingly dense thickets of complexities, the true objects of the lobbyists’ labors were often invisible to the untrained eye. An ambiguous word here, an obscure footnote there, could be worth billions down the road. “What’s interesting,” Gellasch told me, “is that the complexities were added as a result of lobbying by the firms that were going to be affected, as a way to mitigate the impacts.” Now, he said, those complexities are being viewed as regulatory millstones by those same firms, whose reactions he summarized as “Oh, my God, this is so burdensome.”

The tactics were subtle, even ingenious. For example, although the original act applied only to American institutions, major banks, including JPMorgan and Morgan Stanley, lobbied the Federal Reserve to extend the rule to any financial firm with any kind of stake, even a single branch, anywhere in the United States—the rationale being that American firms would otherwise face a “competitive disadvantage” from their overseas counterparts. They then called on foreign embassies in Washington to say that their banks back home, now limited by the rule to buying only US Treasuries, would consequently be barred from buying bonds issued by their own governments. Predictably, this generated a torrent of high-level complaints to the US government from foreign capitals demanding that the rule be changed. (It was, at least partially.) “The criticism of foreign governments on behalf of their banks is helping US banks fight the rule,” the Stanford finance professor Anat Admati told Bloomberg News at the time. “It also muddies the water, shifting the debate away from the main issue, which is reducing the risks banks impose on the real economy.”

Was it in the interest of the banks to make the regulations more complex? “Of course!” Volcker assured me. “It’s endemic in the United States between the lawyers and bankers. ‘You’ve got a regulation? Let’s find a way around it.’ Then the regulator has to respond. ‘All right, we’ll make a rule against that.’ If that’s the environment, you’re going to get detailed regulations. It’s maximized in this case, where you’ve got five different agencies, all with a proprietary interest in their own authority.”

The Volcker Rule was hardly the only component of Dodd–Frank to be undermined by semi-covert means. Over the past two years, the law professor and former regulator Michael Greenberger has been investigating another such maneuver, and an especially artful one. This was in connection with an effort to regulate swaps contracts, including credit default swaps—“the killer that caused the meltdown,” in Greenberger’s words—by requiring that the bulk of them be traded on public exchanges, with deals recorded in a database available to regulators. In the run-up to the crisis, for example, no one had understood that AIG was on the hook for bets it could not possibly pay. Had such information been public, the witless insurer’s rush to catastrophe might have been stopped.

The CFTC duly published a “guidance” in July 2013 stating that any foreign affiliate of an American bank “guaranteed” by its corporate parent (generally taken as a matter of course, since no one would otherwise do business with a subsidiary) was subject to the new regulations on swaps trading. The agency’s chair, Gary Gensler, was a former Goldman banker whose enthusiasm for cleaning up Wall Street had attracted the rancor of his erstwhile peers. AIG, Gensler pointed out, had “nearly brought down the US economy” by running its trades through a British subsidiary. With his enthusiastic endorsement, the rule was approved by a majority vote of the commissioners. There was just one dissent, from Scott O’Malia, a former aide to Senator Mitch McConnell.

Given its relevance to the $700 trillion derivatives market, the rule attracted intense scrutiny from interested parties, especially the International Swaps and Derivatives Association, the industry overseer that issues the standard contract for swap transactions. Searching the CFTC guideline’s 84 pages of text and 660 footnotes for crevices that could be expanded into loopholes, ISDA found just what they needed buried, whether deliberately or not, in footnote 563. Referring to the “guaranteed affiliate” requirements of the guidance, the footnote stated:

Requirements should not apply if a non-U.S. swap dealer or non-U.S. MSP [the counterparty, or person on the other side of the trade] relies on a written representation by a non-U.S. counterpart that its obligations under the swap are not guaranteed with recourse by a U.S. person.

There it was, cloaked in bureaucratese. All that was required to dodge the regulation was to state that the foreign subsidiary was “not guaranteed.” Just one month after the CFTC issued its edict, ISDA quietly rewrote its boilerplate swaps contract. According to Greenberger, the organization simply put “amended contract language into the swaps agreement, where you checked the box and said the subsidiary was now de-guaranteed.” On the basis of a single sentence in a single footnote, a major component of the promised reform of the Wall Street casino was “shredded,” Greenberger said, “in a way no one understands.” It was not until the spring of 2014 that anyone at the CFTC realized that a large fraction of all swaps trades were now being run through London or other overseas trading centers.

In August, around the same time that ISDA was amending its contract, Commissioner O’Malia, who had resisted the reform, resigned from the agency to become the head of ISDA, with a salary of at least $1.8 million a year. Meanwhile, very slowly, the CFTC (no longer led by Gensler) creaked into action. Eventually, the agency published a proposal for a rule that would close the loophole. That was in October 2016, one month before Donald Trump was elected president. The proposed reform has not been heard of since.

In April 2012, as regulators and Wall Street haggled over the swaps trading regulations, news broke of a massive prop-trading scandal. As initially reported by the Wall Street Journal and Bloomberg, JPMorgan was facing enormous losses thanks to a series of trades in the synthetic credit portfolio. The group had earlier done well dealing in ABX futures and other derivatives. It had won recent favor at headquarters because of a correct bet the previous year that American Airlines would go bankrupt, netting a $400 million profit. The parent corporation had also funneled much of a recent $100 billion inflow, entrusted by crash-panicked depositors to the “safe” JPMorgan, to SCP for further investment.

But in the early months of 2012, SCP trader Bruno Iksil’s CDS bets cratered. So huge were his losses that traders at other firms dubbed him the London Whale. It appeared to be a clear case of an irresponsible trader gambling away enormous sums—the projected loss ultimately amounted to $6.2 billion of taxpayer-insured deposits—and exactly the kind of action the Volcker Rule was designed to prevent.

Dimon did not help matters by telling analysts that a multibillion-dollar loss was a “tempest in a teacup.” In any event, the bank claimed, this was by no means a case of speculative prop trading, which would be forbidden by the Volcker Rule; it was simply a hedge, offsetting an investment risk with an equivalent bet on the other side. However, when pressed, bank executives appeared at a loss to explain what they were hedging against.

To appease the critics, Iksil and his colleagues in London were offered up in sacrifice, fired on the grounds that they had fraudulently concealed losses. US and British authorities prepared criminal indictments against some of them on the same grounds. (The charges were eventually dropped.)

Sensing that there was a lot more to the story, Carl Levin asked the Senate’s Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations to conduct a proper probe. Equipped with subpoena power to elicit the bank’s cooperation, the investigators grilled executives and pored over thousands of documents. Their eventual report was damning. It flatly asserted that the bank’s Chief Investment Office had

used bank deposits, including some that were federally insured, to construct a $157 billion portfolio of synthetic credit derivatives, engaged in high risk, complex, short term trading strategies, and disclosed the extent and high risk nature of the portfolio to its regulators only after it attracted media attention.

Despite this, noted the report, the bank’s management had insisted they were obeying the regulations. The entire debacle, in Michael Greenberger’s words, was the “number one story showing the danger of naked credit default swaps” and the vital necessity of the Volcker Rule.

Though generally perceived as a case of a rogue trader risking gigantic sums of customers’ money, the JPMorgan meltdown of 2012 was no such thing. Senate investigators concluded that the entire strategy had been directed from a high level, and that the traders, though ejected from their jobs and facing jail time, were not to blame. As a former Senate investigator, who asked not to be identified, confirmed to me recently, “Evidence shows the London traders advised selling the derivatives at a loss, but were overruled and directed to keep trading.”2

The investigators arrived at this conclusion without having actually talked to the traders, who had stayed in Europe, well out of reach of US authorities. Iksil, the so-called Whale (he hates the title), remained secluded in his house in the French countryside about sixty miles from Paris—he declines to say exactly where. He seldom talks to the press. Recently, however, Iksil discussed his story with me over a long phone call, during which he politely corrected, in excellent English and despite a heavy cold, my layman’s misapprehensions about the technicalities of the credit markets.

Unsurprisingly, he agreed with the Senate investigators’ conclusion that he and his colleagues were not to blame for the fiasco. “All the decisions,” he told me, “were made miles away and far above my head.” In his view, the bank was circulating “complete crap about my role.”

He had, he said, been pondering the events over the past five years. He concluded that the whole mess could be traced to the fact that the bank’s Chief Investment Office was required to keep its funds in readily available liquid investments. Instead, the CIO parked its investments in highly illiquid swaps. In 2010, according to Iksil, Dimon and other senior executives had discussed this problem with the OCC regulator, at a time when public anger that not a single bank executive had been charged in connection with the crisis was cresting. As Iksil put it to me, “People were saying, ‘No prop trading. No illiquid stuff.’?”

It would certainly have been possible, Iksil told me, to set aside a reserve against potential losses on these CDS investments, the latter amounting to $40 or $50 billion. But that would have wiped out two years’ worth of earnings. Instead, the bank simply plunged deeper into esoteric credit trades in the expectation that such hedges would lessen the risks associated with the portfolio. However, the market moved stubbornly against JPMorgan’s bets, bringing huge projected losses and a PR disaster when the story broke in the press. Under cover of the furor, Dimon, who Iksil insisted must have personally overseen the entire strategy, was able to get rid of the remaining embarrassingly illiquid assets on the CIO balance sheet by folding them into the company’s investment bank.

Given the outpouring of falsehoods from the banking lobby concerning the Volcker Rule, Iksil’s story seemed plausible enough. SIFMA, for example, had stated that the rule was a “solution in search of a problem,” since prop trading had had nothing to do with the crisis. I quoted this to Volcker. “Didn’t AIG have something to do with the crash?” he responded mildly. “They did a little proprietary trading, as I recall.” (He could have added that the banks were on the other side of AIG’s fatal prop trades.)

No matter. Tim Keehan, a senior official at the American Bankers Association, unblushingly lamented to me that the Volcker Rule had brought about a “reduction in the level of service that customers were formerly used to receiving.” He insisted that the Volcker Rule “has substantially impacted venture capital fund-raising.” He went on to echo a common industry concern and decry the bewildering complexity of the Volcker regulations, ignoring or forgetting that many of the ambiguities had been inserted at the behest of his colleagues. Finally, he bemoaned the lack of liquidity unleashed by Volcker’s rule.3

Dennis Kelleher had no patience with such lines of argument when I spoke to him. After pointing to a recent SEC study confirming that there was no lack of necessary market liquidity, he continued heatedly: “There was certainly massive liquidity before 2008—of worthless securities that crashed the global financial system and almost caused the second Great Depression. It is true that the trading today is way below that, because we’re no longer allowing them to trade in worthless securities. That’s true!”

Among those protesting the Trump Administration’s obvious eagerness to oblige Wall Street has been Senator Merkley of Oregon. Yet when I asked him whether he thought the industry offensive would succeed, his reply was despondent. “I’m afraid it will,” he said.

Acting comptroller Noreika has promised to issue suggested amendments to the Volcker Rule by the spring, but there are grounds for suspecting that it is already becoming a dead letter. Bank analyst Chris Whalen, formerly of the Federal Reserve, told me that a resurgence in credit trading by the banks indicates to him that they’re already “cheating more on Volcker.” He also asked why Goldman was placing bets on the Marcellus Shale with its own funds to begin with, given the restrictions laid down by the rule. “That’s a good question,” he said. “But you can be pretty sure that no regulator is going to ask it as long as the administration is filled with Goldman Sachs executives and Gary Cohn works at the White House.”