Some readers of Martin Amis’s new collection of essays, The Second Plane: Terror and Boredom (Alfred A. Knopf), have found the marriage of nouns in its subtitle a consternation, an inglorious instance of Martin Aimless. “[H]e repeatedly draws a nonsensical analogy between terrorism and boredom,” wrote Michiko Kakutani,

trying in vain to argue that they are flip sides of the same coin. Boredom? Try telling the families who lost loved ones at the World Trade Center or the Pentagon or on United Flight 93 that their relatives and friends died in the opening chapter of the “age of boredom.”

How nonsensical, though, are those two nouns taken together? To ask the question a different way, how unprecedented is such a pairing?

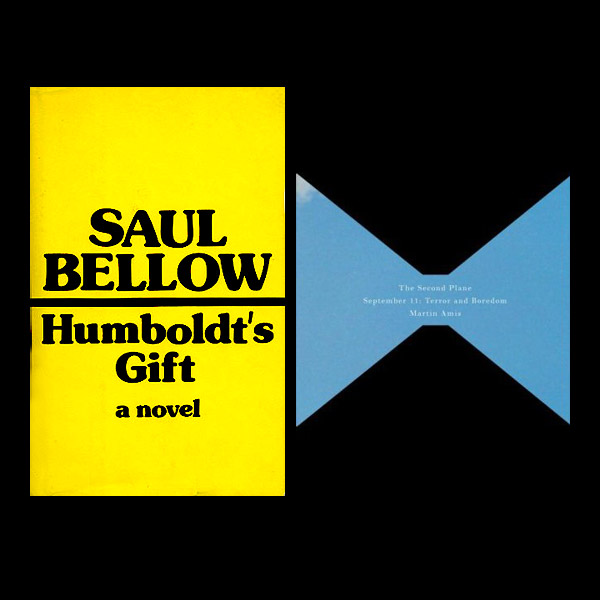

A few weeks ago happenstance led me to an admittedly provisional and narrow answer. I was reading, for no good reason beyond pleasure, Saul Bellow. The novel was Humboldt’s Gift (Penguin Classics), a book which seems to provide the paternity for what Kakutani condemns as Amis’s “nonsensical” pairing. On page 201 the book’s narrator, Charlie Citrine, waits at a courthouse before a meeting with his ex-wife. He’s killing time by going over his “boredom notes”—notes to an essay on the topic that Citrine, a fictional Pulitzer Prize-winner, has been planning, which is to say not writing.

Bellow’s mode in the excerpt below is the lyric, not the analytic; or, if the analytic, the analyric (not a word, my O.E.D. tut-tuts, as I burn with shame). In any case, setting aside the contumacious matter of how well Amis—that great lover of Bellow the writer and the man (see M.A.’s excellent Experience (Vintage))—has managed his own boredom project, consider, at least, the idea that “boredom and terror” might be a good deal more than “nonsensical” after all:

What—in other words—would modern boredom be without terror? One of the most boring documents of all time is the thick volume of Hitler’s Table Talk. He too had people watching movies, eating pastries, and drinking coffee with Schlag while he bored them, while he discoursed theorized expounded. Everyone was perishing of staleness and fear, afraid to go to the toilet. This combination of power and boredom has never been properly examined. Boredom is an instrument of social control. Power is the power to impose boredom, to command stasis, to combine this stasis with anguish. The real tedium, deep tedium, is seasoned with terror and with death.

There were even profounder questions. For instance, the history of the universe would be very boring if one tried to think of it in the ordinary way of human experience. All that time without events! Gases over and over again, and heat and particles of matter, the sun tides and winds, again this creeping development, bits added to bits, chemical accidents–whole ages in which almost nothing happens, lifeless seas, only a few crystals, a few protein compounds developing. The tardiness of evolution is so irritating to contemplate. The clumsy mistakes you see in museum fossils. How could such bones crawl, walk, run? It is agony to think of the groping of the species–all this fumbling, swamp-creeping, munching, preying, and reproduction, the boring slowness with which tissues, organs, and members developed. And then the boredom also of the emergence of the higher types and finally of mankind, the dull life of Paleolithic forests, the long long incubation of intelligence, the slowness of invention, the idiocy of peasant ages. These are interesting only in review, in thought. No one could bear to experience this. The present demand is for a quick forward movement, for a summary, for life at the speed of intensest thought. As we approach, through technology, the phase of instantaneous realization, of the realization of eternal human desires or fantasies, of abolishing time and space the problem of boredom can only become more intense. The human being, more and more oppressed by the peculiar terms of his existence–one time around for each, no more than a single life per customer-has to think of the boredom of death. O those eternities of nonexistence! For people who crave continual interest and diversity, how boring death will be! To lie in the grave, in one place, how frightful!