A few weeks ago, I received an email advertising a free public event at Harvard University. “Award-winning and bestselling author Jonathan Franzen reviews The Corrections with James Wood, Harvard Professor of the Practice of Literary Criticism.”

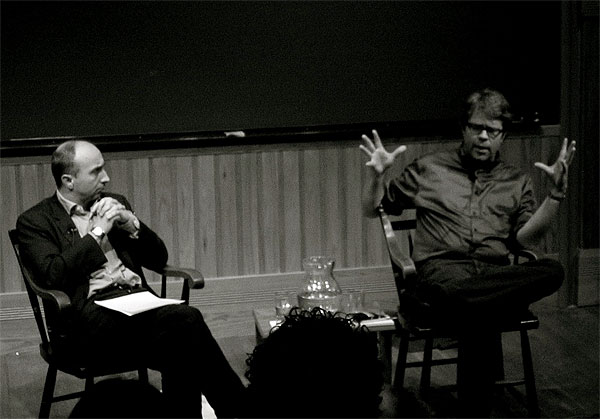

The late-April conversation was held in an amphitheatric Harvard classroom that, on the evening in question, quickly filled to capacity, with late-arrivers left to stand in the rear. After an introduction by Wood of Franzen’s work-to-date, including an approving précis of The Corrections, the two men spoke amiably for about an hour. Wood asked Franzen, who has written about the solitariness of writing, whether he saw himself nonetheless as part of a community of writers. “I have friends.” Franzen said dryly, earning a big laugh, “[But] I don’t feel particularly communitarian.”

A few minutes later Franzen wondered, “Do writers ever have communities?”

“There are some examples,” said Wood, “of very lucky geographical communities like the one that James and Conrad and Stephen Crane were in, when they were all writing in the same county in Sussex…but those are freakish, I think. It’s presumably very hard to do in America. Not living in New York, one always imagines that New York is the place, or at least Brooklyn, where writers are continually bringing pots of sugar around to each other’s door and getting an egg in return and then talking about fiction.” Franzen suggested that this hadn’t been his experience: “I’ve spent three nights of my entire life in Brooklyn. They weren’t happy nights. [Audience laughter.] No offense to Brooklyn.”

Talk continued apace, about reading and writing; about Franzen’s 1996 essay in this magazine on the state of the novel; about “difficult” writers such as William Gaddis, about whom Franzen, in 2002, wrote in The New Yorker; and about the balance that a contemporary novelist might strive for between difficulty and approachability.

“Didn’t you feel in The Corrections,” Wood asked, “that you did manage to pull it off both ways, that you achieved that? You wrote a difficult book that enormously appealed to a large popular audience.”

“I can’t answer that question,” Franzen said. Then he ventured: “That’s what I was trying to do. I was very consciously trying to do it.”

“Well,” said Wood, “I think a million people [think you] did.” Again, the audience laughed. “And that’s fine–there’s no reason why you should be able to assess the success of your book.”

Nonetheless, as Wood and Franzen’s friendly conversation steered into the oceanic subject of The Novel, away from the local waters of The Corrections, I wondered if Wood was correct. Recasting his particular statement more generally: is there no reason why a writer should be able to assess the success of his own book? Put another way, I wondered if a writer should be able, if not to assess, then at least to discuss the choices—and in the case of a very good and careful writer such as Franzen, the scrupulous, deliberate and purposeful choices—that are made all but endlessly on the road to a completed work of art.

And so, when Franzen and Wood fielded questions at the end of their hour, I asked the following: “The desire for a writer to find readers is perfectly understandable, just as it is for a writer to fear judgment. Some contemporary writers, among them David Foster Wallace, [say they don’t] read any criticism, and I wonder what role criticism has played in your life as a writer, particularly criticism of your work. And in the instance of James’s review [of The Corrections, in The New Republic, in 2001], it would seem to be a missed opportunity (given how infrequently critics and writers actually have conversations about work and given how diminished the reading culture certainly is) not to know: when you read James’s review of your book; what you thought of it; and, as an ambitious novelist who is writing a fourth novel now, one presumes, to what extent any of the things that James said in his review affect you or afflict you as somebody who’s attempting to create a better and more ambitious book still.”

Franzen’s answer was frank, generous, thoughtful, and, I think, usefully revealing about the impediments, both philosophical and practical, that may come up when any of us might wish to discuss a work of art, whether with its creator or with one of its admirers (or detractors). And I’ll share it on Wednesday.