At dawn on April 23, 1899, Vladimir Vladimirovich Nabokov was born in St. Petersburg. One hundred years later, The Nabokovian, the twice-yearly publication of the International Vladimir Nabokov Society, conducted “The Nabokov Prose-Alike Centennial Contest.” Appearing in its Spring issue of that year, six pages of the journal contained five prose passages that varied in length but were similar in their showy, playful styles. Each passage was marked with a number, but no author’s name was given

“[S]urprisingly,” wrote the journal’s editor, Stephen Jan Parker, in the subsequent issue, “no one succeeded in distinguishing the original passages from the imitations. For the record, #2 and #5 were the passages written by VN, taken from his incomplete and unpublished novel, Original of Laura. Passages #1, #3, #4 were submissions created by contest entrants.”

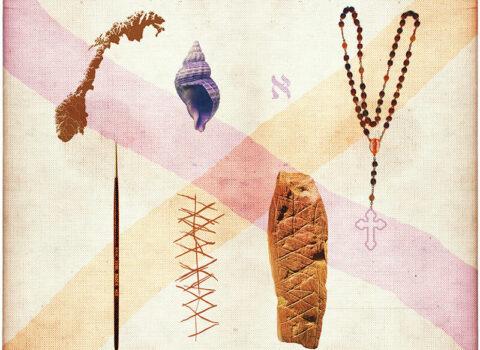

Lately, readers have heard more than a little about that incomplete and unpublished novel, once at risk of being burned in accordance with authorial fiat but now to be published sometime hence as Nabokov’s final work. A picture, even, of the manuscript–glowing pale gold against an infernal red background, a partial arm, it seems, hoisting the tidy squat tower — has surfaced in France, and details have risen with it.

The title, say, in its complete form, is now said to be The Original of Laura: Dying is Fun. Dmitri Nabokov, the writer’s son and heir, has, from his home in Palm Beach, recently provided a French journalist with details about the book: the main character of Laura is Philip Wild,

a brilliant neurologist. He is fat, very fat. Comically fat. Comically ugly. And tormented by a marriage to a woman much younger than he and terribly fickle. At a certain moment, he begins, humorously, playfully, to reflect on the question of self-destruction. But soon after, he decides that he absolutely does not want to think about the idea of definitive suicide. He wants, on the contrary, a reversible suicide.

Brian Boyd, author of the unsurpassable two-volume biography, Vladimir Nabokov: The Russian Years & The American Years, is one of the novel’s few readers thus far. In the TLS, Boyd said:

I think it is a fascinating novel. It is very fragmentary, people shouldn’t expect to be swept away. He is doing some very brilliant things with the prose, the story just flashes by, the characters are rather unappealing. It seems a technical tour de force, just as Shakespeare’s later works where he is extending his own technique in very, very concentrated ways. [The text is as] grotesque in some ways as, and unsavoury in different ways from, Lolita. It’s the kind of writing that induces admiration and awe but not engagement.

With all the talk about the novel, though, we seem to have forgotten that some of it can already be read, thanks, of course, to The Nabokovian and their “Nabokov Prose-Alike Centennial Contest.” Although the winner of that contest, Charles Nicol, who seems likely to be this Charles Nicol, received the Grand Prize in the contest (an always welcome $100), for his “unknown section” from Pnin, we readers turned out winners, too. From The Nabokovian’s excerpting of The Original of Laura:

Mr. Hubert had brought his pet a thoughtful present: a miniature chess set (“she knows the moves”) with tickly-looking little holes bored in the squares to admit and grip the red and white pieces; the pin-sized pawns penetrated easily, but the slightly larger noblemen had to be forced in with an enervating joggle. The pharmacy was perhaps closed and she had to go to the one next to the church, or else she had met some friend of hers in the street and would never return. A fourfold smell – tobacco, sweat, rum and bad teeth – emanated from poor old harmless Mr. Hubert, it was all very pathetic. His fat porous nose, with red nostrils full of hair, nearly touched her bare throat as he helped to prop the pillows behind her shoulders, and the muddy road was again, was forever a short cut between here and school, between school and death, with Daisy’s bicycle wobbling in the indelible fog. She, too, had “known the moves,” and had loved the en passant trick as one loves a new toy, but it cropped up so seldom, though he tried to prepare those magic positions where the ghost of a pawn can be captured on the square it has crossed.