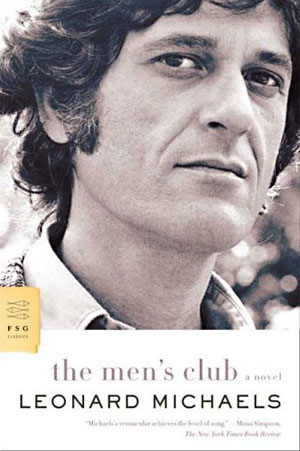

The great mass of everything now being sold and promoted everywhere leaves those of us looking for something particularly good at a loss, in the welter, for where to turn. Last year, the publisher Farrar, Straus and Giroux simplified things for many of us by bringing back into print the work of one of the house’s best writers, Leonard Michaels.

As I wrote in this magazine last year, Michaels’s reputation had, during the second half of his writing life, waned in its cultural presence while, at the same time, strengthening in aesthetic excellence. As such, and thankfully, The Collected Stories was hailed as a necessary volume for anyone interested in beauty, rigor, and mastery in the story form.

It’s a bottomless collection, one that showcases the unusual coexistence of lyricism of line and clarity of idea that was a hallmark of Michaels’s style. And happy though one might have been to have seen so complete and appropriate a volume as The Collected Stories,

As comfortable writing perceptive literary criticism as he was profiles of writers or personal essays, Michaels always brought rigorous intelligence and an understated sensitivity to his subjects. In their lightness of movement and depth of attainment, his longer essays resemble most those of Michel de Montaigne.

[Archive]

Fiction

Jealousy

March 1997

After a Fight, from Sylvia

December 1992

Essays

The Action of Metaphor

January 1987

Literary Talk

December 1987

Diary of an Ex

December 1989

The Irresponsibility of Feelings, on Leonard Michaels

A comprehensive corroboration of that claim will come in 2009, when FSG publishes The Essays of Leonard Michaels. Readers properly eager for that collection, however, may begin their weekends with a short essay by Michaels drawn from its pages. “My Father” takes as its subject that most familiar of subjects, but treats it with an uncommon perfection typical of all Michaels’s work.

With thanks to Katharine Michaels and Janklow & Nesbit for permission to reprint.

My Father

By Leonard Michaels

Six days a week he rose early, dressed, ate breakfast alone, put on

his hat, and walked to his barbershop at 207 Henry Street on the Lower

East Side of Manhattan, about half a mile from our apartment. He

returned after dark. The family ate dinner together on Sundays and

Jewish holidays. Mainly he ate alone. I don’t remember him staying

home from work because of illness or bad weather. He took few

vacations. Once we spent a week in Miami and he tried to enjoy

himself, wading into the ocean, being brave, stepping inch by inch

into the warm blue unpredictable immensity. Then he slipped. In water

no higher than his pupik, he came up thrashing, struggling back up

the beach on skinny white legs. “I nearly drowned,” he said, very

exhilarated. He never went into the water again. He preferred his

barbershop to the natural world; retiring, after thirty-five years,

only when his hands trembled too much for scissors and razors, and

angina made it impossible for him to stand for hours at a time. Then

he took walks in the neighborhood, carrying a vial of whiskey in his

shirt pocket. When pain stopped him in the street, he’d stand very

still and sip his whiskey. A few times I stood beside him, as still as

he, waiting for the pain to end, both of us speechless and frightened.

He was vice-president of his synagogue, keeping records, attending to

the maintenance of the building. He spoke Yiddish, Polish, maybe some

Russian, and had the Hebrew necessary for prayers. He spoke to me in

Yiddish until, at about the age of six, I began speaking to him mainly

in English. When he switched from one language to the other, I’d

rarely notice. He could play the violin and mandolin. As a youth in

Poland, he’d been in a band. When old friends visited our apartment,

he’d drink a shnaps with them. He smoked cigars and pipes. He read the

Yiddish newspaper, the Forward, and the Daily News. He voted

Democratic but had no faith in politicians, political systems, or “the

people.” Aside from family, work, and synagogue, his passion was

friends. My mother reminded me, when I behaved badly, of his

friends. She’d say, “Nobody will like you.” Everybody liked Leon

Michaels.

He was slightly more than five feet tall. My mother is barely five

feet. Because I’m five nine, she thinks I’m a giant. My father came

from Drohiczyn (Dro-hee-chin), a town on the river Bug near the

Russian border. When I visited Poland in 1979, I asked my hosts about

Drohiczyn. They said, “You’ll see new buildings and Russian troops. No

reason to go there.” I didn’t go there. It would have been a

sentimental experience, essentially empty. My father never talked

about the town, rarely said anything about his past. We also never had

deep talks of the father-and-son kind, but when I was fifteen I fell

in love and he said a memorable thing to me.

The girl had many qualities–tall, blond, talented musician–but

mainly she wasn’t Jewish. My father learned about her when we were

seen together watching a basketball game at Madison Square Garden,

among eighteen thousand people. I’d been foolish to suppose I could go

to the Garden with a blonde and not be spotted. My father had many

friends. You saw them in his barbershop, “the boys,” snazzy dressers

jingling coins in their pockets or poor Jews from the neighborhood who

came just to sit, to rest in their passage between miseries. Always a

crowd in the barbershop–cabdrivers, bookies, waiters, salesmen. One

of them spotted me and phoned my father. When I returned that night,

he was waiting up with the fact. He said we would discuss it in the

morning.

I lay awake in anguish. No way to deny the girl I loved. I’d been

seeing her secretly for months. Her parents knew about the secrecy. I

was so ashamed of it that when I called for her I’d ring the bell and

then wait in the street. She urged me to come upstairs, meet her

parents. After a while, I did. They understood. Her previous boyfriend

was the son of a rabbi.

In the morning my father said, “Let’s take a walk.” We walked around

the block, then around the block again, in silence. It took a long

time, but the silence was so dense it felt like one infinitely heavy

immobilized minute. Then, as if he’d rehearsed a speech and dismissed

it, he sighed. “I’ll dance at your wedding.”

Thus we spent a minute together, father and son, and he said a

memorable thing. It is concise, its burden huge. If witty, it’s in

the manner of Hieronymus Bosch, making a picture of demonic gaiety. My

wedding takes place in the middle of the night. My father is a small

figure among dancing Jews, frenzied with joy.

For a fifteen-year-old in love, this sentence was a judgment,

punishment, and release from brutal sanctions. He didn’t order me not

to see her. I could do as I pleased. As it happened, she met someone

else and broke up with me. I was very hurt. I was also relieved. My

father danced at my wedding, twelve years later, when I married

Sylvia. Black-haired. Dark-skinned. Jew. Because her parents were

dead, the ceremony was held in our apartment. Her aunts and uncles sat

along one wall, mine along another. The living room was

small. Conversation, forced by closeness, was lively and nervous. The

rabbi, delayed by traffic, arrived late, and the ceremony was

hurried. Everyone seemed to shout instructions. Did she circle me or I

her? My father was delighted. When Sylvia and I fought, which was

every day, she’d sometimes threaten to tell my father the truth about

me. “It will kill him,” she said.

I’d tried once to talk to him about our trouble. He wouldn’t hear

it. “She’s an orphan. You cannot abandon her.”

If he ever hit me, I don’t remember it, but I remember being

malicious. My brother, three years younger than I, was practicing

scales on my father’s violin. When he finished, he started to carry

the violin across the room. I put out my foot. He tripped, fell. We

heard the violin hit the floor and crack. Quicker than instantly, I

wanted to undo the act, not trip my brother. But it was done. I was

stuck with myself. I think I smiled. My father looked at the violin

and said, “I had it over twenty years.”

Maybe I tripped my brother because I’m tone-deaf. I can’t learn to

play a musical instrument. Nothing forgives me. I wish my father had

become enraged, knocked off my head, so I could forget the incident. I

never felt insufficiently loved, and yet I think: When Abraham raised

the knife to Isaac, the kid had it good.

In photos, however badly lit or ill-focused, my father looks like

himself. I never look like myself. This isn’t me, I think. Like a

baby, my father is inevitably himself.

My father never owned a car or flew in an airplane. He imagined no

alternatives to being himself. He had his family, his friends, his

neighborhood, synagogue, and the hectic variety of human traffic in

the barbershop and the streets. Looking out my window above San

Francisco Bay, I think how my father saw only Monroe Street, Madison

Street, and Clinton Street. For thirty-five years, he walked to work.

I was in London, returning from three months in Paris, when he

died. My flight to New York had been canceled. I was stranded, waiting

for another flight. Nobody in New York knew where I was. I couldn’t be

phoned. The day after the funeral, I arrived. My brother met me at the

door of the apartment and told me the news. I went alone to my

parents’ bedroom and sat on the bed. I didn’t want to be seen crying.

A great number of people visited the apartment to offer condolences

and to reminisce. Then a rabbi came, a tiny, fragile man dressed in

black, with a white beard twice the length of his face. It looked like

the top of his shirt. He asked my mother to give him some of my

father’s clothes, particularly things he’d worn next to his skin,

because he was a good man, very rare. As the rabbi started to leave

with a bundle of clothes in his arms, he noticed me sitting at the

kitchen table. He said in Yiddish, “Sit lower.”

I didn’t know what he was getting at. Did he want me to crouch? I was

somehow susceptible to criticism.

My mother interceded. “He feels,” she said. “He feels plenty.”

“I didn’t ask how he feels. Tell him to sit lower.”

I got up and left the kitchen, looking for a lower place to sit. I was

very angry but not enough to start yelling at a fanatical

midget. Besides, he was correct.

One Friday night, I was walking to the subway on Madison Street. My

winter coat was open, flying with my stride. I wore a white shirt and

a sharp red tie. I’d combed my hair in the style of the day, a

glorious pompadour fixed and sealed with Vaseline. I was

nineteen-years-old-terrific. The night was cold, but I was hot. The

wind was strong. My hair was stronger. It gleamed like black, polished

rock. As I entered the darkness below the Manhattan Bridge, where it

strikes across Madison Street and makes a high, gloomy, mysterious

vault, I met my father. He was returning from the barbershop,

following his usual route. His coat was buttoned to the chin, his hat

pulled down to protect his eyes. He stopped. As I approached, I saw

him study me, his creation. We stood for a moment beneath the bridge,

facing each other in the darkness and wind. An American giant, five

feet nine inches tall. A short Polish Jew. He said, “Button your

coat. Everybody doesn’t have to see your tie.”

I buttoned my coat.

“Why don’t you wear a hat?”

I sighed. “I’m all right.”

“You need a haircut. You look like a bum.”

“I’ll come to the barbershop tomorrow.”

He nodded, as if to say “Good night” and “What’s the use.” He was on

his way home to dinner, to sleep. He’d worked all day. I was on my way

to sexual adventure. Then he asked, “Do you need money?”

“No.”

“Here,” he said, pulling coins from his coat pocket. “For the

subway. Take.”

He gave.

I took.