I can picture my brother as a handsome young boy, all eyes and nerves, traipsing about in the muggy drizzle of Glasgow after his tipsy father. In Dublin I have more than once seen children, younger than my brother was at that time, trying to lead a staggering mother home.

Who wouldn’t leap to read more by the author of these sentences? “All eyes and nerves,” is terse and visible description despite abstractness. “Muggy drizzle” on one side of the see-saw line is rhythmically and melodically balanced by “tipsy father”. And then there’s the unspooling of effect in the second sentence that roots us in place (“In Dublin”), plants a sociological seed (“I have more than once seen”), adds actors (“children”), personalizes them unobtrusively (“younger than my brother was at that time”), offers a hopeful gerundive (“trying to lead”) that simultaneously suggests its possible opposite (for trying suggests one might fail) and then concludes, after all that careful effort, with a few, gutting last steps (“a staggering mother”—worse, somehow, than a “a staggering father”) before the sentence shuts, before the destination (“home”) can be attained.

“I have read the book twice,” T. S. Eliot said of the whole from which the lines above are clipped,

and find myself fascinated and repelled by the personality of this positive, courageous, bitter man who was a prey to such mixed emotions of affection, admiration, and antagonism—a struggle in the course of which…he saw his famous brother, at certain moments, with a startling lucidity of vision.

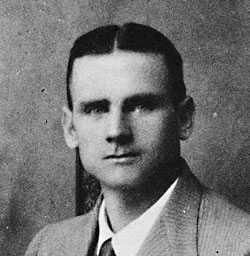

The book in question is My Brother’s Keeper, its author Stanislaus Joyce. Younger by three years, Stanislaus bore, in Richard Ellmann’s phrase “his curious burden with nobility and discomfort.” The burden, to anyone who has read Ellmann’s biography of the elder Irish author, that of being “among the first to recognize James Joyce’s genius,” and that of realizing, however much he idolized and adored him, that “his character [was] ‘very difficult.’”

There are a number of interesting fraternal pairs in literature. The incompatible frères Theroux; the unequal Manns; the incongruous William and Henry James. Of accounts of frustrated fraternity, though, Stanislaus’s book is likely the most humanly complex, in part due to its complex subject, but more purposefully still due the great talent Joyce the younger had as an observer. And then there was also his talent for self-abnegation. “This is coloured too highly, like a penny cartoon,” wrote Stanislaus, next to one of his routinely excellent descriptions of his brother—a staggering brother.