How does one best write about horrible things? By “best” I mean how does one write truthfully about horrible things? By “horrible,” I mean any experience that, because of its extremity, lies just outside of life. By “outside of life”—given that we cannot know literally what lies outside of life, which is to say beyond the borders of birth and death, assuming they are borders and not barriers—I mean those experiences so extreme in their violence that most of us will never live them, and so remain outside of our lives until we hear about their place in the lives of others. Experiences so extreme: murder; rape; torture; slaughter of people; slaughter of animals; ruin of lives—destruction of things that cannot be replaced.

How does one best write about horrible things? By “best” I mean how does one write truthfully about horrible things? By “horrible,” I mean any experience that, because of its extremity, lies just outside of life. By “outside of life”—given that we cannot know literally what lies outside of life, which is to say beyond the borders of birth and death, assuming they are borders and not barriers—I mean those experiences so extreme in their violence that most of us will never live them, and so remain outside of our lives until we hear about their place in the lives of others. Experiences so extreme: murder; rape; torture; slaughter of people; slaughter of animals; ruin of lives—destruction of things that cannot be replaced.

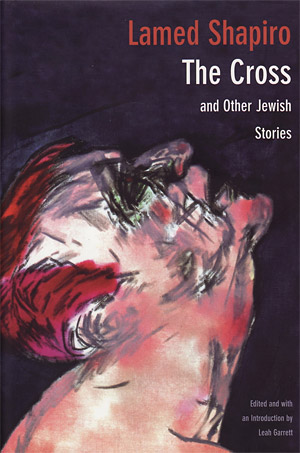

How does one best serve, in writing, the irreplaceable? The best writing seems to suggest that there is only one answer to this question; it convinces us not of debatable facts but of incontrovertible truths. True facts: not redundant, oxymoronic. Non-fiction: that which traffics in facts that would be taken as truths. Fiction: that which traffics in truths uncomplicated by fact. Lamed Shapiro (1878-1948) was a name not known to me before the fiction writer David Bezmozgis suggested I read The Cross and other Jewish Stories (Yale, 2007), edited and with a useful introduction by Leah Garrett. The title story of Shapiro’s collection, “The Cross,” begins in the mode of the hobo picaresque, albeit in a cadence in which readers of Babel, Bellow, and Michaels will recognize rhythmic, sonic, and syntactic antecedence:

Sleep came whenever night fell: in the open fields or under a tree somewhere in the woods. Sometimes on dark nights we “hopped a train.” That is, we went onto the roof of a car and hitched a little ride. The train flew like an arrow. A sharp wind hit us in the face, carrying the smoke of the locomotive in bits of cloud, dotted with many sparks. The prairie ran and circled around us, and breathed deep, and spoke quickly and quietly, with a multitude of sounds in a multitude of tongues. Distant planets sparkled over us, thoughts entered and swum about our heads, such strange thoughts, wild and open as the voices of the prairie: they seemed each unconnected to the next, they seemed knotted and linked and ringed together. And at the same time, beneath us, in the cars, people sat and reclined, many people, whose path was set and whose thoughts were confined; they knew from whence they came and whither they went, and they told of it to each other and yawned while they would do it, and they would slumber, not knowing that above, atop their heads, there were two free birds resting a while on their way. From where? Whither? At dawn we would jump down onto the ground and go to snatch a chicken or catch fish with makeshift poles.

Hitched not a ride but “a little ride.” Not a strong but “a sharp wind.” The smoke of a locomotive, always rising in nebulous clouds, is here given as being “in bits of cloud,” and not just that–for these bits are “dotted with many sparks,” which is something that one needs to be close to the smoke in order to see.

The closeness of the writer to the thing experienced is not a matter of experience. Experience helps but does not alone convince. Seeing, whether in eye or mind, convinces of truth. And what follows in “The Cross” is, despite the makeshift poles that pop up in the last line of the paragraph above, no fishing trip. The picaresque becomes a horror story of exacting and convincing truth. More on that on Wednesday.