In these pages, in 1947, Jacques Barzun reviewed Malcolm Lowry’s novel, Under the Volcano. Barzun’s review, a terse paragraph in a long essay that bundled many books together with the titular twine of “Moralists for Your Muddles,” was short and sour: he found the Lowry a waste of time. The paragraph in which he dispatched it ran as follows:

Mr. Malcolm Lowry’s Under the Volcano strikes me as fulsome and fictitious. Mr. Lowry is also on the side of good behavior, eager to disgust us with sub-tropical vice. He shows this by a long regurgitation of the materials found in Ulysses and The Sun Also Rises. But while imitating the tricks of Joyce, Dos Passos, and Sterne, he gives us the mind and heart of Sir Philip Gibbs. His three men and lone woman are desperately dull even when sober, and, despite the impressive authorities against me on this point, so is their creator’s language. I mean the English language, since Spanish also flows freely through his pages. “The swimming pool ticked on. Might a soul bathe there and be clean or slake its drought?… The failure of a wire fence company, the failure, rather less emphatic and final, of one’s father’s mind, what were these things in the face of God or destiny?” What indeed when so reported? Mr. Lowry has other moments, borrowed from other styles in fashion–Henry James, Thomas Wolfe, the thought-streamers, the surrealists. His novel can be recommended only as an anthology held together by earnestness.

Lowry was upset by this summary judgment, and wrote Barzun a letter. For students of civil behavior, not to say critics and novelists who might think to make of their public literary activity an object lesson in adult solicitude, Lowry’s post-mortem attempt to stay his executioner is instructive. File it with Philip Roth’s (unsent) letter to Diana Trilling on the subject of her dismissal of a novel of his. Lowry’s own reply only further confirms my sense that one can do better, even in this uncivil time, when receiving criticism however harsh (not to say when meting it out) than the hurling of insults. It is perhaps useful to be reminded that when people exchange words about art, we are witnesses not, as the lately popular coinage has it, to a “Literary Smackdown!” but to civilization—a term forever in need of definition.

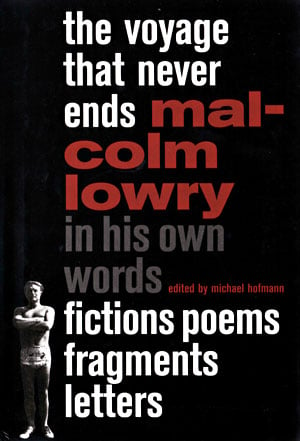

And so, for your weekend read, I propose Lowry’s response to Barzun. It is drawn from the excellent new anthology of Lowry’s uncollected writings, The Voyage that Never Ends, well-assembled by Michael Hofmann (New York Review Books). With thanks to Jim Rutman of Sterling Lord Literistic and Edwin Frank of New York Review Books for assistance and permissions. Thanks as well to the civilized Kelly Zinkowski, who put Lowry’s letter under my nose.

To Jacques Barzun

Dollarton, B.C., Canada

May 6, 1947

Dear Mr. Barzun:

You’ve written, to my mind, such a horribly unfair criticism of my book, Under the Volcano, that I feel I may be forgiven for shooting back.

Granted that it has been overpraised to the extent where an unfavorable review seems almost welcome, and granted that your review may end by doing me good, it rankles as an even harsher criticism, if just, could never do; and I feel that this is not only unsporting but weakens your whole general argument; people simply won’t listen to your very necessary truths if you do this kind of thing once too often.

Ah ha, I can hear you saying, well I can tear the heart out of this pretty damned easily, I can smell its derivations from a mile away, in fact I need only open the book at random to find just what I want, just the right food for my article: I do not feel you have made the slightest critical effort to grapple with its form or its intention. What you have actually succeeded in doing is to injure a fellow who feels himself to be a kindred spirit.

I do not think there was any need, either, to be so insulting about it. You are intitled to “fulsome and fictitious” and you can say if you wish (though it is not specifically true and there is certainly no irrefutable evidence of the former) that I am “on the side of good behavior and eager to disgust you with tropical vice.” But when you say “He shows this by a long regurgitation of the materials found in Ulysses or The Sun Also Rises” are you not overstepping the mark in an effort to be scornful? For while few modern writers, myself included, can have altogether escaped the influence, direct or indirect, of Joyce and Hemingway, the “materials” in the sense you convey are not to be found in either of these books. “And while imitating the tricks of Joyce, Dos Passos and Sterne, he gives us the heart and mind of Sir Philip Gibbs.” What tricks, precisely, do you mean? A young writer will naturally try to benefit and make use of what he has read, as a result of which, especially in technique, what Van Gogh I think calls “design-governing postures” are from time to time inevitable. But where I found another writer in the machinery–the writer you are reading at the moment, Richards has pointed out, is nearly always the villain–I always did my utmost to sweat him out. Shards and shreds of course sometimes remain; they do in your style too. But so far as I know I have imitated none of the tricks of the writers you mention, one of whom at least once testified to my originality. As a matter of fact–and to my shame–I have never read Ulysses through, of Dos Passos I have read only Three Soldiers, and of Sterne I have never been able to read more than one page of Tristram Shandy. (This of course does not rule out direct influence, but what about what I’ve invented myself?) I liked The Sun Also Rises when I read it 12 years ago but I have never read it since nor do I think I’ve ever been particularly influenced by it. Where the Volcano is influenced, its influences are, for the most part, other, and for the most part also I genuinely believe, absorbed. Where they are not you can put it down to immaturity; I began the book back in 1936 when I was 27 and doubtless, in spite of many rewritings, it carries a certain stamp of that fact. As for Sir Philip Gibbs are you not just being gratuitously cruel? Perhaps if you would really read the book you would see that quite a lot of it is intended to be–and in fact is–funny, as it were a satire upon myself. Nor, I venture to say, do I think that, upon a second serious reading, you would find it dull.

After Sir Philip Gibbs I can almost forgive you for juxtaposing at random two not very good passages from Chapters III and IX as though they were contiguous, as an example of bad reporting. But even if those passages are not so hot, what of the justice of this kind of criticism? I’d like to know what you’d do with the wretched student who loaded his dice like that for you.

The end, I suppose, is intended to crush one completely. “Mr. Lowry has other moments, borrowed from other styles in fashion, Henry James, Thomas Wolfe, the thought-streamers, the surrealists. His novel can be recommended only as an anthology held together by earnestness.”

Whatever your larger motive–which I incidentally believe to be extremely sound–do you not seem to have heard this passage or something like it before? I certainly do. I seem to recognize the voice, slightly disguised, that greeted Mr. Wolfe himself, not to say Mr. Faulkner, Mr. Melville and Mr. James–an immortal voice indeed that once addressed Keats in the same terms that it informed Mr. Whitman that he knew less about poetry than a hog about mathematics.

But be that as it may. It is the “styles in fashion” that hurts. Having lived in the wilderness for nearly a decade, unable to buy even any intelligent American magazines (they were all banned here, in case you didn’t know, until quite recently) and completely out of touch, I have had no way of knowing what styles were in fashion and what out, and didn’t much care. Henry James’ notebooks I certainly have tried to take to heart, and as for the thought-streamers (if you’re interested in sources) William would doubtless be pleased. And I’m glad at least it was earnestness that held the anthology together. Nonetheless I shall laugh–and I hope you with me–should in ten years or so the Voice again be heard decrying some serious contemporary effort on the grounds that its author is simply regurgitating the materials to be found in Lowry. I shall laugh, but I shall on principle sympathize with the author, even if it is true.

Be this as it may. Any other kind of duello being inconvenient at this distance, I had begun this letter with the intention of being, if possible, as intolerably rude as yourself. I even bought an April Harper’s to provide myself with material and sure enough I found it springing up at me, just as to you, from my work, your ammunition: for did I not immediately find you lambasting Señor Steinbeck in vaguely similar terms, although at much greater length, accusing him of almost everything except stealing his bus from me–you of course didn’t know I had one, it is in Chapter VIII (a crime I may say of which he is innocent and vice versa) and speaking of his anti-artistic emotion of self-pity, by which I take it you do not of course mean your own anti-artistic emotion of self-pity by any chance?

There is an interesting passage here too:

In the makers of the tradition, that is to say in Balzac, Dickens, Zola, Hardy, Dostoevsky, down to Sinclair Lewis and Dos Passos, there is an affirmation pressing behind every grimness, an anger or enthusiasm of despair which endows mud with life and makes it glow like rubies. The energy of mind makes even a surfeit of facts bearable, while plot enmeshes the characters so completely that the reader is compelled to believe in a fated existence, at the very moment when he knows that he is only the sport of the writer’s will.

Good: but why, at that rate, are you so ready to jump upon the affirmation pressing behind the grimness in the Volcano? So ready to jump upon it indeed as soon as you saw it (because it was in capital letters doubtless) that you quite missed the anger or the enthusiasm of despair that it was following? Did you not trample the one to death without even taking the trouble to see if the other was there at all, without taking any trouble, in short, except to exhume Sir Philip Gibbs from his dull grave in order to have a cheap sneer at my expense? And if so, why? I could tell you, but this is as far as my rudeness will take me.

For one thing, I have just got another batch of reviews, all of them good, and all of them more irritating than yours. For another, the book is to be translated into French: the very tough editors, I am relieved to say, think more highly of it than you, which is something. And for another I just have news from England that one of my best friends–Anna Wickham, the poet, if you’re interested–has just hanged herself in London.

God has raised his whip of Hell

That you be no longer weak

That out of anguish, you may speak

That out of anguish, you may speak well.

She once wrote. My wife, by a coincidence having bought me a week ago, in Canada, the only edition of her poems (praised by D. H. Lawrence–and why didn’t you drag him in?) that can have been sold in 20 years, bought them for me indeed two days before Anna died. So life is too short or something.

And the grammar of this letter is bad. And it will remain so. So, doubtless, are the semantics. And the syntax. And everything else.

With the general tenor of your criticism in Harper’s I am enormously, as I hinted, in accord. That for instance political books should be read with the historian’s scepticism, and with the historian’s willingness to see the drama of both sides, that we suffer from intellectual indigestion, philosophic bankruptcy, and adulterated “brews” of one kind or another–be they behavioristic or what-not, that we are being done down by half thoughts, regurgitated unthoughts found in so and sohow true: I might remind you, though, that there are sometimes deeper sources and not everything comes up your own service elevator.

I think I said that the Volcano had been over praised and also praised for qualities it probably doesn’t possess and I think that one of the things I wanted to say was that that seemed no good reason for you to tear it to pieces for faults it doesn’t possess either.

I wish, sincerely, that you would read it again, and this time, because you don’t have to write about it, look instead for what may be good in it. It sings, I believe, considerably–the whole thing–in the mind, if you can stand the partial bankruptcy in character drawing and what actually is fictitious about it, the sentences like Schopenhauer’s roast geese stuffed with apples.

But on the side of good conduct no. I myself savagely reviewed it for a preface for the English edition–though they would have none of it–thus–never mind the “thus” but ending: All applications for use by temperance societies should be accompanied by a case of Scotch addressed to the author. Now put it back in the three-penny shelf where you found it.

Moreover I had even toyed at one time rather lovingly with the notion of having Hugh and Yvonne killed off while too sober and the Consul returning cheerfully and drunkenly to his duties to mescal and the British Crown under a miraculously transformed and benign Poppergetsthebotl.

You might also remember that so far as the latter was concerned I was doing what I fondly believed (in spite of L’Assommoir) to be a pioneer work. The Lost Weekend et al did not come along until, as always happens, it was virtually finished, and at that for the fifth time. Moreover it will both horrify and relieve you to learn that it was only the third of a book, if complete in itself, most of the rest having been destroyed by fire.

And if you want sources–what about the Cabbala? The Cabbala is only in the sub-basement of the book but you would discover therein that the Cabbala itself is identified with the “garden” and the abuse of wine with the abuse of magical powers, and hence with the destruction of the garden, and hence with the world. This myth may have somewhat confined me: for though one might sympathize with Mephistopheles, Faust is a different matter. But perhaps I cite this only to show you how much more loathsome the book might have been to you had I put this on the top plane. I very much believe in what positive merits the book has, however. (I don’t know if Sir Philip Gibbs ever thought about the Cabbala, I have a gruesome suspicion that that is precisely the sort of thing he may have thought about.)

At all events I am now writing another book, you will be uninterested to learn, dealing roughly speaking with the peculiar punishment meted out to people who lack the sense of humour to write books like Under the Volcano. So far, I am pretty convinced that nothing like it has been written, but you can be sure that just as I am finishing it–

Sans blague. One wishes to learn, one wishes to learn, to be a better writer, to think better, and one wishes to learn, period. In spite of some kind of so-called higher education (Cambridge, Eng.) I have just arrived at that state where I realized I know nothing at all. A cargo ship, to paraphrase Melville, was my real Yale and Harvard too. Doubtless I have absorbed many of the wrong things. But instinct leads the good artist (which I feel myself to be, though I say it myself) to what he wants. So if, instead of ending this letter “may Christ send you sorrow and a serious illness,” I were to end it by saying instead that I would be tremendously grateful if one day you would throw your gown out of the window and address some remarks in this direction upon the reading of history, and even in regard to the question of writing and the world in general. I hope you won’t take it amiss. You won’t do it, but never mind.

With best wishes, yours sincerely,

Malcolm Lowry

P.S. Anthology held together by earnestness–brrrrrr!