Some people are fussy about their books, insisting that the margins within remain pristine, treating each volume as a sacred object. Although I have a fair number of first editions, and like having them (I most like being able to find them for a song–Pnin, by Vladimir Nabokov, hardcover first edition, $6–score; thank you, Bookfinder), I don’t treat my books tenderly. I don’t beat them up, but reading is involving, and I usually need to write in the book I’m reading.

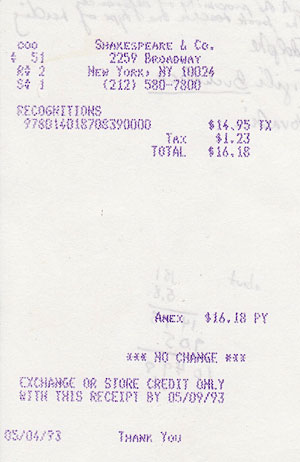

Most of my marginalia is in a storage facility, out of reach and forgotten. This past weekend, though, I needed to find an old notebook, and so had to search through my fifty boxes to find it. It was in the forty-eighth box–but on the way I happened upon a great many other books that I couldn’t resist bringing home. Here at hand, for example, is my copy of William Gaddis’s The Recognitions. I bought it in May of 1993 (receipt used as bookmark) and read it later that year, in October, after I quit a job in Manhattan and went to live in a small town on the Adriatic coast of Italy. In my seaside bed, under an oil painting of Jesus with movie-star hair and a burning heart levitating in his chest, I read Gaddis’s first novel. Many of the margin notes I made in the book are referential: Gaddis packs in several libraries’ worth of references, and there are many terms (“homoousian”) and names (“Vainiger”) to chase down. Many of the notes are personal and, with time, somewhat cryptic: a moment in the narrative that reminded me of a moment in my life, and which I scribbled about in the white space. Roughly half of these seem to refer, at fifteen years’ remove, to another person.

But some notes are more useful. If “sentimentality” is mentioned on page 111, in reference to its absence (according to Wyatt Gwyon, the book’s central character) from flamenco music, it is nice to see, on page 127, that I’ve flagged another reference to “sentimentality” in depictions of the dead Christ being mourned by his mother. And there I have a range of other numbers that refer to later pages where the theme of sentimentality is reprised.

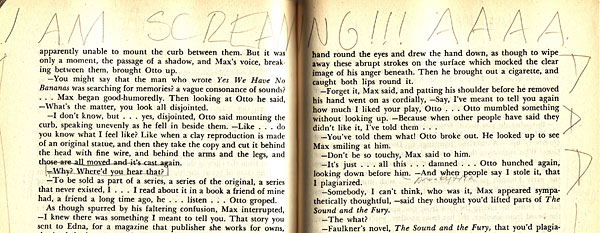

Of course, with Google Books, and even with Amazon’s “Search Inside” feature, one can do all of this without a pencil, much less a book. Even so, it’s a source of some pleasure to come upon one’s older books, and to see the work inside, both of its writer and of its reader, who, on some pages–such as during a notorious eighty-page party scene told almost entirely in dialogue–plum lost his mind: