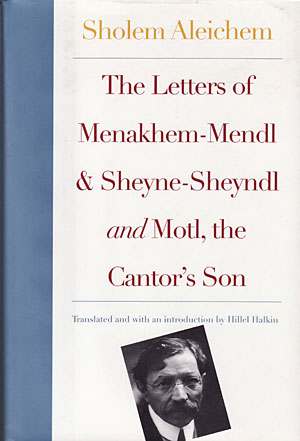

“The things I’ve seen in Antwerp are not to be described,” Sholem Aleichem (1859–1916), né Rabinovich, writes in his novel Motl, the Cantor’s Son. Aleichem wrote in Yiddish, and the colloquial and clear English of the above belongs to Hillel Halkin. Aleichem’s syntax could not be confused, that is to say confounded, in misery of mistakenness, in a moment of misguidedness, with that of Henry James. (As my Yiddish is limited to a list of interjectives, I depend upon Halkin’s report of his source as truthful.)

In college I wrote a paper on Thomas Mann’s The Magic Mountain that traced leitmotivs throughout the book to bolster my (long-forgotten) argument. My professor, upon returning the paper, patiently explained that Helen Tracy Lowe Porter, a druggist’s daughter from Towanda, Pennsylvania, and Mann’s erstwhile voice in English, had a habit of serial inconsistency when it came to Mann’s German: words Mann used repeatedly, my professor said, HTLP democratized into different synonyms; where Mann varied his usage, HTLP regularized it. I can’t verify the accuracy of my professor’s diagnosis of HTLP’s editorial disorder, but I can say that such reading experiences shape the caution I now take when talking about work in translation.

So said, Halkin’s Aleichem is a writer to read, in English. “The things I’ve seen in Antwerp are not to be described,” is a sentence that, of course, initiates the narrator’s descriptions of (what else) Antwerp. It’s a softly funny statement, one meant to suggest the sheer stupefaction one would have courted in opening one’s eyes in Antwerp at all. What would one see:

Every day new people turn up here. They’re mostly poor or crippled or have eye problems. “Trachoma,” it’s called. Whatever it is America doesn’t want it. You can have a thousand diseases, be deaf, dumb, and lame—it’s all right if you don’t have trachoma.

Fans of Woody Allen, Jonathan Foer, Jerry Seinfeld, Leonard Michaels, Larry David, Philip Roth, Saul Bellow, and so forth, might note a sympathetic syntactical–not to say historical–temperament. The best humor comes out of suffering of some kind. Loss leads to laughs, eventually. Seinfeld of the missing sock, of course, is merely a literalizing of loss–itself a kind of loss. Here’s another kind, again from Aleichem’s Motl, a comic novel begun in 1906 and never finished, a book of losses not to be described:

Big Motl and I have another friend. His name is Mendl. He’s stuck in Antwerp too. Not on account of his eyes, though.

Mendl lost his family in Germany. On the train crossing Germany, he says, there was nothing to eat but salt herring. He was burning with thirst and got off at a station to look for water and the train pulled out and left him without a ticket or a kopeck to his name. Since he didn’t speak the language, he pretended to be deaf and dumb. He wandered from one end of Germany to the other until he ran into a party of emigrants who felt sorry for him and took him to Antwerp.