If it were your ambition to convince a friend that her deeply held belief, cherished since childhood—say, that apple cider is undrinkable, undigestible, and unbearable—is dangerously off the mark, you need only offer her a taste either to confirm or complicate her certainty. Good will is the only lever required, in such matters of taste, to cut a towering absolute down to something that allows for the sight not merely of doubt but, potentially, delight. If it were your ambition, however, to convince your friend not that cider is yummy but that reading is as well—a fine pastime at minimum and, at best, a life-saver—you would be, to use a sophisticated bit of exegetical shorthand favored by the literary: nuts.

You can no more convince an adult that reading matters than you can build a new foundation to save a house already fallen into collapse. For an adult to be a reader, the child they were must have been a reader: for a child to be a reader, an adult within its immediate arc must be a reader. Books that would sway the non-reading adult towards the practice of reading, and which would try to sway such an adult to do something they do not (reading) by doing something they won’t do (reading) drive me, therefore, bananas. They make, for all their good will, precious little practical sense.

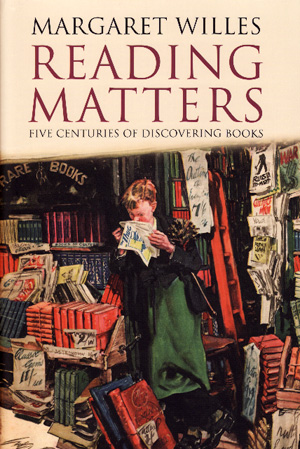

When I saw the cover of Margaret Willes new book, Reading Matters (Yale), I confess to having been so blinded by its title that I did not bother to look, for several days, at its cheering sub: Five Centuries of Discovering Books. “This book sets out to examine how people bought and acquired books over the past five hundred years, thus combing two of my favourite activities, shopping and reading,” Willes’s book begins. Though I happen to be someone who hates shopping as much as he loves reading, I was very engaged by Willes’s walk through the history of one of our less reprehensible regions of conspicuous consumption.

“I cannot live without books,” Willes tells us Thomas Jefferson told John Adams, in a chapter on Jefferson’s 6,487 volume library which—after the 3,000 volumes in our de facto national library, the Library of Congress, were burned to nothing by the British, in 1814—he sold to the United States as a replacement (two thirds of which, in 1851, were lost to yet another fire). Willes is a knowledgeable guide to the material and a clear, unfussy writer, one more eager to share what she knows than to convince us we should know it. Words aside, the book is also pleasurably and usefully full of pictures. I could stare at the photo of a Penguincubator all day, now that Willes has convinced me of its existence, and of how it came to be.