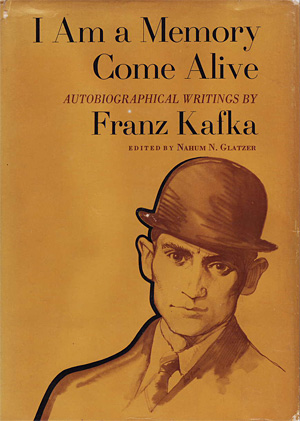

“The frequent references to Max Brod, Prague, insomnia, headache, have not been included in the Index.” So runs the inadvertently hilarious advisory sentence to the index of I Am a Memory Come Alive, a gathering and sequencing of Kafka’s so-called “autobiographical writings” put out by Schocken in 1974. I like a list that takes a friend, a city, a condition, and a pain and, by eliding them, equalizes them. Taken together, the quartet conspires to a kind of story. Throw a conjunction or two in there and you have a thumbnail biography: Max Brod and Prague, but insomnia and headache.

“The frequent references to Max Brod, Prague, insomnia, headache, have not been included in the Index.” So runs the inadvertently hilarious advisory sentence to the index of I Am a Memory Come Alive, a gathering and sequencing of Kafka’s so-called “autobiographical writings” put out by Schocken in 1974. I like a list that takes a friend, a city, a condition, and a pain and, by eliding them, equalizes them. Taken together, the quartet conspires to a kind of story. Throw a conjunction or two in there and you have a thumbnail biography: Max Brod and Prague, but insomnia and headache.

“The reader of Kafka will want to know,” runs the flap copy of the book above, “what kind of man the author was, how he lived, what he cared for, what he was like as a lover.” Oy! Do we, really, want to learn about that last bit? Really? Will my reading of “In the Penal Colony,” be radically transformed by a knowledge of Kafka’s pillowy likes? “Fortunately,” the flap flaps on, “Kafka tells us about his life, though often covertly, and the present volume facilitates a better understanding of that life and its relationship to his work.”

Well, no, it doesn’t, or so I’d contend. We don’t even have to go so far as to dip into The Sacred Wood to justify the claim. “Yesterday and today wrote four pages, trivialities difficult to surpass,” is an entry from Kafka’s diary, 7 August 1914. Naturally, there’s more to Kafka’s intimate notations than such seethings against self. In tone, though, that kind of entry is the rule. Headaches predominate, and are interesting of themselves, to those of us interested in the pain of others. But how Kafka managed to transform such commonplace into uncommon fiction is not a story told in his “autobiographical writings.” Thankfully, that’s a story that cannot, though not for lack of trying, be told.