For those who read books as part of their habit of being, end of the year “Best Books” lists tend to offer little in the way of surprises. Odds are, whatever organ has generated the hyperventilatorily-hyped top ten will do little more than feature titles that were most rapturously received in its pages during the preceding months—the listmaking imperative more labor-saving device than critical act, less critical coming-to-terms than buyer’s guide.

That said, who among us doesn’t need direction when it comes to spending our bottomless surplus of dollars? In the spirit of fiduciary bonhomie, I devote today’s entry to my favorite book of the year. For the cynical among you, I offer the preambular attestation that I am not, in fact, kidding about my pick. The choice is sincere, the book sublime (and very expensive!). For, although a number of the year’s best novels may be said to contain a world (2666, surely), only one book this year contains the world.

In the era of the GoogleImage, an atlas—any atlas—could seem superfluous. After all, any of us can point and click our way to a picture of our houses seen from space (a fact that has become so central to modern living that one of the year’s best novels, Netherland, turned that fact into a moment of very moving fiction). And yet, it is precisely that kind of solipsism that web research reinforces and risks rewarding—a narrowing, not a broadening, of vision. As a means of finding out about the world, the web is, in one way, without peer, but the narrowness of self tends to misdirect our use of that broad thing: our use of it mirrors our own constriction. MySpace indeed.

An atlas, by contrast, is an OurSpace. More than merely being about the world, it bounds—binds—the world, and in a way that’s freeing. An atlas, any atlas, commands our interest, directs it outwards, forces us, agreeably, usefully, not to see ourselves, for once, as central to our world. We search an atlas for ourselves in vain: always, it exceeds us. This formal difference is productive. To be forced to encounter the world not on our terms but on the world’s terms teaches us a kind of intellectual and social humility.

As a primer on such foundational humility, my pick for the year’s best book is, far and away, the Oxford Comprehensive Atlas of the World. I’ve lost the past two days in this fifteen-pound, six-hundred-page, gold-gilt-edged, three-red-ribboned feast. And whereas, when I lose a day online, I feel, afterwards, somewhat unclean, my disappearance into the enormous and seemingly unending procession of (wonderful-smelling, by the way) pages in the O.C.A.W. makes me feel full of virtue.

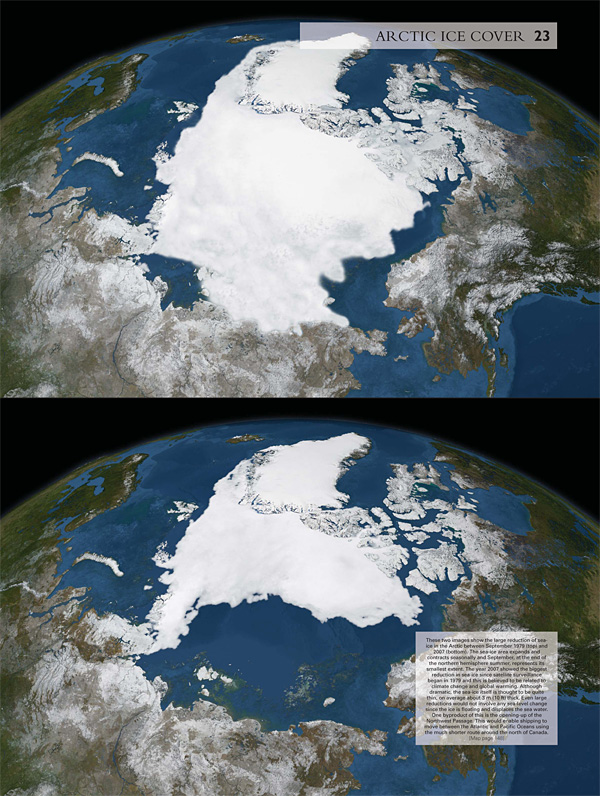

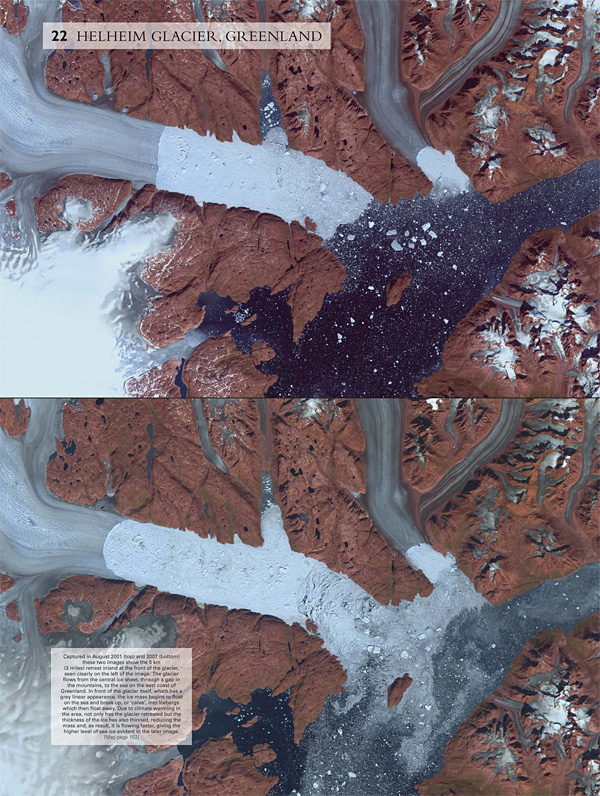

The O.C.A.W. is in thirds: front matter, maps, and index. The front matter offers 100 pages that provide any child or adult an adequate primer on the breadth of topics that concern and characterize our planet. Statistics charting a range geological, climatological and economic metrics; full color gatefold images of the earth from space that one can simply stare into and which offer another, more manifest kind of metric…

…and fifty further gatefold pages devoted to such timely topics as “Biodiversity” and “Climate Change,” as well as timeless ones like “Conflict,” “Landforms,” “International Organizations,” “Cities,” and even dear old “Moon.”

Each of these provides a little lesson that takes about fifteen minutes to read and offers a pocket education. An education that those who spend a great deal of time trying to snooker children into abiding will be surprised to see done so convincingly, and so beautifully, by a book. The O.C.A.W., in its form, its cunning use of images and intelligent marshalling of text, exploits the book as a form. It will remind anyone who kindles of the limits of portability. The world is massive; a book devoted to it should be too, and that mass, as much as the fineness of the editorial choices throughout the O.C.A.W., argue for the bestness of this book—not to say the book—better than any other book this year.

One could argue that such topics are more instantly available and updateable online, but productivity doesn’t pay all debts. Happy to run the risk of coming off as helplessly antique, I’d mention that the O.C.A.W. has an added bonus feature: it becomes a social activity. One reads it on the carpet, sprawled. One gets in the way of the people one lives with, who then join in. This leads to many pleasurable kinds of wrestlings, and trivia that, for once, isn’t trivial.