There is no translation of any worthwhile book that hasn’t had its sometimes vigorous detractors. Jerome, who gave us the Vulgate, was forced to flee Rome to finish his work in Bethlehem when the Roman clergy got wind of his decision to translate from Hebrew sources (and, worse still, into the everyday Latin of Romans). Tyndale, who gave us the first English Bible with wide distribution was strangled and burned at the stake for his trouble (the charge was heresy). So it goes.

The Aeneid is a different sort of holy book. It has found its English voice countless times. The most recently heralded version was done by Robert Fagles, and written about approvingly in these pages by Rafil Kroll-Zaidi. I like the Fagles too, but first liked the Fitzgerald. He hooked me early in that unfinished epic’s first book with a series of lines I love. The moment comes as Aeneas, who had ?ed Troy during its destruction by the Greeks, is later marooned by a storm on an unknown shore. Through wilderness and woods, he comes upon a glorious city. Beautiful though it is, he worries that he and his hidden ship will be taken for in?dels and destroyed like so much else they’ve already lost. Still brave, Aeneas enters the temple at the city center in the hope that he might make himself known to its elders. While he waits uneasily, he notices that upon the walls of the temple are many murals. The scenes that they depict seem familiar to Aeneas, and so he examines them. He does not believe his eyes: they are panoramas of Troy. Of the great war, the battles with the Greeks, the terrible invasion, the torching of the city—images of Trojan bravery even in defeat, everywhere visible within this foreign shrine:

Here Aeneas

Halted, and tears came.

“What spot on earth…

Is not full of the story of our sorrow?

Look, here is Priam. Even so far away

Great valor has due honor; they weep here

For how the world goes,and our life that passes

Touches their hearts. Throw off your fear. This fame

Insures some kind of refuge.”

He broke off

To feast his eyes and mind on a mere image,

Sighing often, cheeks grown wet with tears…

He stood enthralled, devouring all in one long gaze.

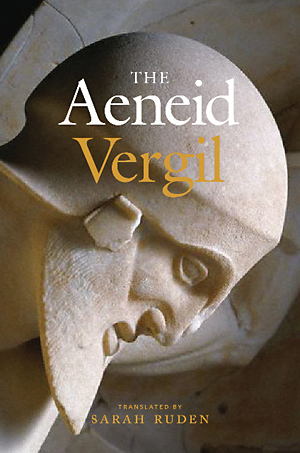

Here, Aeneas finds solace in the ordered universe of art in the wake of life’s disorder. Sarah Ruden, who has also done versions of Lysistrata and The Satyricon, now has done an Aeneid (Yale) that gives readers another chance to find solace in Virgil. Ruden’s approach is very different, as is the yield. “This is the first translation since Dryden’s that can be read as a great English poem in itself,” Garry Wills wrote of the Ruden recently. While I wouldn’t disagree that Ruden’s version, taken in as a whole, coheres as poem, and a rich one, to say it is the first that can be read as a great English poem is going too far. Both the Fagles and the Fitzgerald did that (and still do that) for me.

Ruden’s Virgil seems notable instead for a kind of austerity, a Roman plainness. Here are her versions of the lines I like from Fitzgerald:

He halted, weeping: “What land isn’t full

Of what we suffered in that war, Achates?

There’s Priam! Even here is praise for valor,

And tears of pity for a mortal world.

Don’t be afraid. Somehow our fame will save us.”

With steady sobbing and a tear-soaked face,

He fed his heart on shallow images.

A very different flavor comes through, and one better appreciated not in small tastes but in a full plate. So, for your Weekend Read, I suggest Book 1 of Virgil’s Aeneid, translated by Sarah Ruden (PDF download). Thanks to Yale University Press for permission to reprint.