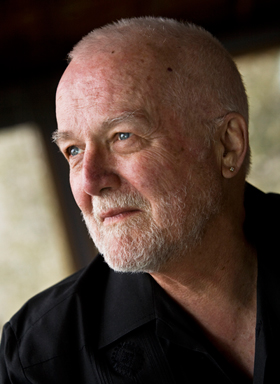

A Conversation With Russell Banks

“[T]o be an artist . . . you really have to blast the launch pad to get liftoff, scorching everything and everyone around you, and you cause a lot of damage sometimes.”

Russell Banks is the author of many essays, stories, and novels, including last year’s Lost Memory Of Skin (Ecco/HarperCollins). His story “Christmas Party” was published in the December issue of Harper’s Magazine. Like much of his fiction, it takes place in the small Adirondack town of Keene, where Banks lives during the warmer months. He spends the winter in Miami, which is where he was when he spoke to me on the phone about holidays, class divisions, and the craft of fiction.

JB: “Christmas Party,” Continental Drift, and Rule of the Bone all begin just before Christmas, Affliction begins on Halloween, and The Reserve begins on July 4. Are you drawn to rituals?

RB: I’ve never noticed it — you’re quite right, of course. It’ll force me to rethink my opening gambits. I think that it makes sense — narrative sense, and maybe dramatic sense — to begin a story not on a random date taken from the calendar but to mark it in a larger way than as just another day in the life, or a dark and stormy night. All stories, anciently, are looking for some connection to the cosmos, or the calendar, or the big clock — some way to get the machinery operating in the narrative, and why not? As readers I think we look for that as well.

JB: In fact, a section of Rule of the Bone appeared in the 1992 Christmas issue of the New York Times Magazine.

RB: I was just recently joking with some students and told them, if you really want to publish your story, you should give it the name of a holiday.

JB: When Harold Bilodeau, the protagonist of your story in this month’s magazine, goes to his ex-wife’s Christmas party, he notices that she has jumped classes; her new husband is a contractor, not a builder like Harold, and their house is fancy, and Sheila kisses him on the cheek, which she never used to do. You’ve written about class in almost every work, and usually from the point of view of the underdog. Have you ever been drawn to writing from the perspective of characters with money and power?

RB: I’ve written about people with money and power in a novel called The Reserve, and I think there I probably started to veer toward a more ironic approach regarding the characters, which is not characteristic of my writing. I’m not an ironist. And whether I was successful or not in that I don’t know. I felt sympathetically toward the characters, especially the female characters in that story, but again it was because they had less power than the others. I think I inevitably end up feeling a special kind of sympathy for people whose lives are shaped and controlled and manipulated by people with more power than them.

JB: In Dreaming Up America (2008), your collection of essays, you considered the idea that it takes three generations for an American family to produce an artist: the first generation has menial jobs; the second has professional jobs; the third can pursue art or leisure.

RB: That’s John Adams’s template. And I actually think it’s false; it doesn’t really describe what usually happens in becoming an artist or writer. It would be nice if you had two generations preceding you to then make it possible for you to become an artist, but that rarely happens and it certainly didn’t happen in my case. More often in America, someone invents himself as a writer or artist, and does it against the wishes of those who surround him — his family and others — and, as a result, has to expend an enormous amount of energy justifying to himself or herself this enterprise. It can put you on the defensive for a long time, and make you insecure socially and otherwise. But I think it’s much harder than just simply being given the privilege, the kind of entitlement, that it takes to be an artist. You really have to blast the launch pad to get liftoff, scorching everything and everyone around you, and you cause a lot of damage sometimes.

JB: Do you feel part of the daily life of Keene, or does your station as its most famous chronicler put you outside of it?

RB: It doesn’t, I don’t think. In “Christmas Party,” in fact, there are people who are real. I showed the manuscript to Dave Deyo, who owns Baxter’s, and I said, “Dave, I wrote this story, and you don’t really appear in it — but your place does and your name does. Do you mind?” And he said “Good publicity, good publicity.”

I know what you’re asking, though. There is a kind of voice that I like that describes in an intimate way the goings-on in the community; I first managed to hear it and then to use it on the page in a group of stories called Trailerpark. I really like the idea of having someone living in the town who is not telling a story about him or herself but about other people: a witness and a chronicler. And the voice in this story is an attempt to get at that again — a little more personalized than a straight objective narrator.

JB: The idea of the chronicler makes me think of another technique that you frequently use, in which a secondary character narrates the story of the protagonist.

RB: In certain novels and stories, I needed a character to tell the story who was different than the person whom the story was about, because that person was either too inarticulate or didn’t know his own story. The way that Wade Whitehouse doesn’t know his own story in Affliction. Or, in the case of Cloudsplitter, with John Brown, in a way he’s too iconic, almost too operatic a character, for me to get away with him telling his own story, and his rhetoric would have been too heightened. I needed somebody who was close to him but also just slightly detached as well, and his son, Owen Brown, who’s an old man, turned out to be the solution.

JB: Returning to the subject of using real people in your stories, do you ever use your own ex-wives or ex-girlfriends as models for your women?

RB: No. And if I did I would never admit it.

JB: So are all of your women made up whole cloth?

RB: Out of whole cloth, yes.

JB: What is your experience of writing from a female point of view?

RB: I’ve done that often enough without any misgivings or any greater apprehension than with any other kind of narrator. I know what women sound like when they’re talking to men. I don’t know what they sound like when they’re talking to women. I mean, women talk very differently about their bodies if a man is listening, and they talk very differently about their sex lives, about children, about each other — so many things. About men, certainly. So you have to figure out whom they’re talking to first. Both Hannah Musgrave in The Darling and my other female narrators — Nichole Burnell and Dolores Driscoll in Sweet Hereafter — are talking to people that I really, fully imagined first. Once their audience is clear to me, I know how to address their voice. I know what level of diction to use, and what inflection and intonation to reach for. And what data, what information they’d like to provide — or withhold.

JB: Writing sex seems to come naturally to you. Do you have any rules?

RB: I’ve always believed that the hotter the content, whether it’s sex or violence or high drama of whatever sort, the cooler the prose should be. I think I’ve learned that over the years and have come to trust it more as I’ve gotten older.

JB: Does some of that happen when you rewrite?

RB: Yeah, but I can see it coming. Maybe in the past I would have had to rewrite more to find that cool tone than I do now. I know how to get there a little more easily — more efficiently, let’s say.

One thing, though. When I was young, I didn’t know what I was doing, and I didn’t realize it was necessary to writing, that you not know what you’re doing. And as I’ve gotten older it’s gotten more difficult for me to find ways not to know what I’m doing. But it’s just as necessary as it was when I was young, and so in this funny way my work has gotten more radical.

JB: Radical?

RB: I plan less and I know less and less about the mystery I’m working with. Not just structurally but thematically — the material itself.

JB: Can you give an example of the kind of mystery you mean?

RB: Well let’s take “Christmas Party.” Once I got into the story, I didn’t know what this passive man, this stoical but passive man, was going to do in order to deal with his pain. I knew that he had a great deal of pain that he was denying and trying to evade in every possible way, but I didn’t know how such a man would deal with the pain of rejection and abandonment and betrayal. But I was stuck after the first couple of pages with a man who was being very passive about it, and stoical and in denial about it. And only bit by bit and piece by piece as the story came together did it become gradually and slowly clear to me that it would take an act of mild aggression against his ex-wife in order for him to become first of all an interesting character to me and to any reader. He’d have to commit some act of mild aggression against her in order to have some sort of moral center and to have processed what happened to him in a moral way, and a psychologically plausible way. But I didn’t know that until I got him into that nursery with that baby and saw him respond to that baby’s existence.

JB: It’s an uncomfortable scene. It’s not funny, exactly, but it could almost be funny.

RB: It seems to me that humor and violence are almost inextricably linked. Both often arise out of frustration and anger, and often appear at the same time in the same place. They’re situational in a sense. Suddenly they erupt into the story.