They longed to see one another again, but it would have been impossible. They dreamed of one of those long conversations that one never has on earth, but which one projects so easily at midnight, alone and wise; words are not rich enough nor kisses sufficiently compelling to repair all our havoc. — Thornton Wilder, The Cabala

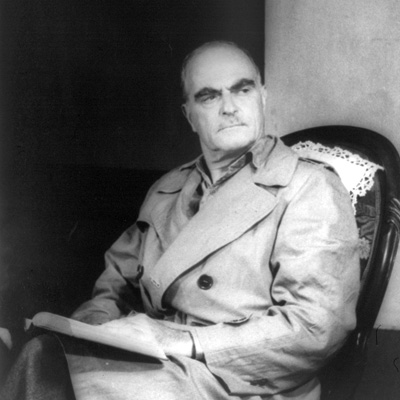

Portrait of Thornton Wilder, as Mr. Antrobus in “The Skin of Your Teeth.” Photograph by Carl Van Vechten, courtesy the Library of Congress, Van Vechten collection

When I began to read Thornton Wilder’s fiction, I was immediately taken with the dry, sad comedy of his prose. His first novel, The Cabala, is packed with aphorisms, sardonic observations, and the kind of subtle wit we usually associate with the English comic fiction of the 1920s, in particular with such books as Ronald Firbank’s Vainglory, Aldous Huxley’s Crome Yellow, and Evelyn Waugh’s Decline and Fall, as well as that slightly earlier model and masterpiece, Norman Douglas’s South Wind.

Among the Wilder works I cite in my essay in the January issue of Harper’s, The Cabala, in particular, deserves to be better known, in part for its deliciously worldly prose. The book, in which a young American observes the love lives and daydreams of a circle of decadent and religious cosmopolitans in Rome, displays a slightly brittle, polished French manner—perhaps overpolished and even bookish at times. Yet the precisely engineered syntax of its sentences, combined with its striking similes and elegant diction, contrive to make it quite palatable:

We pursued the Via Po for a mile or two and alighted at the ugliest of its houses, an example of that modern German architecture that has done so much for factories.

Nature had decided to torment this woman by causing her to fall in love (that succession of febrile interviews, searches, feints at indifference, nightlong solitary monologues, ridiculous visions of remote happiness) with the very type of youth that could not be attracted by her.

I returned late to my rooms through the deserted streets — at the hour when the parricide feels a cat purring against his feet in the darkness.

That first sentence neatly holds back its punchline for its final word, while the second traces, through its diction and sibilant alliterations, the sorrowful course of our unreciprocated infatuations. As for the last quotation, I’ve sometimes wondered whether Orson Welles — whose early career Thornton Wilder helped along — remembered that sentence and suggested it for the famous scene in The Third Man when the cat reveals Harry Lime standing in the darkened doorway.

Sometimes, as in the following passage, Wilder aims to compose a virtual prose aria. A handsome young adolescent named Marcantonio is initiated into sex by some Brazilian girls at Lake Como. Disillusionment ensues:

Suddenly his eyes had been opened to a world he had not dreamed of. So it was true that men and women were never really engaged in what they appeared to be doing, but lived in a world of secret invitations, signals and escapes! Now he understood the raised eyebrows of waitresses and the brush of the usher’s hand as she unlocks the loge. It is not an accident that the wind draws the great lady’s scarf across your face as you emerge from the door of the hotel. Your mother’s friends happen to be passing in the corridor outside the drawing-room, but not by chance. Now he discovered that all women were devils, but foolish ones, and that he had entered into the true and only satisfactory activity in living — the pursuit of them. One minute he was exclaiming at the easiness of it; the next he described its difficulties and subtlety. Now he sang the uniformity of their weakness and now the endless variety of their temperaments. Next he boasted of his utter indifference and his superiority to them; he knew their tears but he did not believe they really suffered. He doubted whether they had souls.

What I love about this paragraph is Marcantonio’s sudden existential realization that nothing is as it seems, that the surface manners and relations of men and women are just trumpery, and genteel society largely a façade. Sex — those “secret invitations, signals and escapes” — pervades and undermines human intercourse. The world is ultimately but a stage, and the best players are all students of Erving Goffman, the sociologist who opened our eyes to the subtleties of “relations in public.” Women, in particular, are reduced — in Marcantonio’s adolescent view — to sexual predators. All this Wilder sets forth with a sorrowful zest, rising to the remarkable last sentence. Marcantonio, it almost goes without saying, comes to a tragic end.

Throughout his work — whether in fiction or drama, letters or essays — Wilder showed he could write every kind of prose, from the elevated and philosophical (The Woman of Andros) to the down-home and vulgar (Heaven’s My Destination). While I’ve emphasized here what one might call Wilder’s early “European” manner, I can’t forbear transcribing a passage from Heaven’s My Destination in which Wilder blends the Homeric catalogue with the open-shirted, all-American exuberance of Walt Whitman. His hayseed Don Quixote, the textbook salesman George Brush, begins his annual road trip to the institutions of higher learning in the American Southwest:

On being discharged from the hospital Brush set out again on that long swing of the pendulum between Kansas City and Abilene, Texas, that was his work. At Abilene he waited his turn in the halls of Simmons University, McMurray College, and Abilene Christian College. He visited Austin College at Sherman, Baylor College at Belton, and Baylor University at Waco. He visited Daniel Baker College and Howard Payne College at Brownwood; he visited the Texas Teachers College at Denton, Rice Institute at Houston, Southwestern University at Georgetown, and Trinity University at Waxahachie. He looked in at Delhart and Amarillo. He went down to San Antonio to see Our Lady of the Lake and to Austin to place an algebra at St. Edward’s University. Returning through Oklahoma, he visited the state university at Norman, the Baptist University at Shawnee, the college at Chickasha, the Agricultural and Mechanical College at Stillwater. He digressed into Louisiana and called at Pineville and Ruston; he spent a solitary Christmas in Baton Rouge. Arkansas tempted him to Arkadelphia and Clarksville and Onachita . . .

This is show-offy, yes, but marvelous. Through his cadences, supported by occasional alliteration and the sheer uniqueness of the place names, Wilder creates a sense of epic timelessness. To make a list like this read like a poem is no mean achievement.

In The Bridge of San Luis Rey, Wilder reminds us that style should serve not only readers, but also a particular vision of existence. The Marquesa’s letters, he writes, were admired for their exquisite prose, such that her son-in-law “thought that when he had enjoyed the style he had extracted all their richness and intention, missing (as most readers do) the whole purpose of literature, which is the notation of the heart.” In his own books Thornton Wilder’s own style may vary, but it always evokes the still, sad music of our lives.