At Night We Walk in Circles

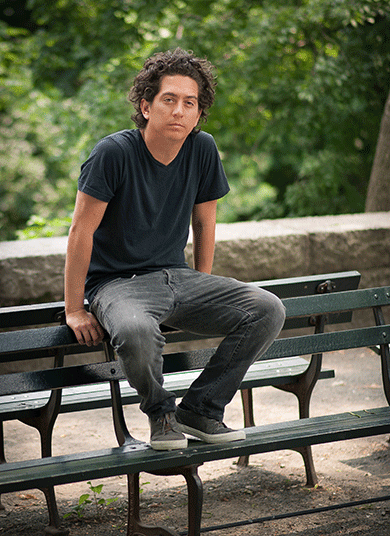

Daniel Alarcón on the actor as character, foreshadowing as bravado, and the visceral nature of curiosity

Daniel Alarcón’s second novel, At Night We Walk in Circles, published in October by Riverhead Books, is a strange and compelling book, a hybrid of journalistic and novelistic techniques, and an interrogation and dramatization of the process of storytelling. The novel follows an unnamed narrator in an unnamed South American country as he excavates the story of a young actor, Nelson, and his travels with the radical theater troupe Diciembre. Beyond the many accolades he has received for his fiction, Alarcón is an accomplished journalist, and readers of Harper’s Magazine may recognize some features of the prison he describes in the novel (where it is known as the Collectors) from his last article for the magazine, “All Politics is Local.” I put six questions to him about the book.

1. At Night We Walk in Circles seems to have grown out of certain pieces of your past fiction and non-fiction work. When did you know you were going to write this novel, and what additional research did you do for it?

I wouldn’t say I did any additional research; in fact, I’ve never been very good at that. What I do instead is pursue the interests I’m passionate about, often for years, without worrying too much about what I’m going to do with this knowledge. In the course of writing this novel, I came to know the inside of Peru’s largest prison, Lurigancho, and know it fairly well, know it well enough to believe I could write about this place in fiction. But the novel itself was already underway by the time I wrote that piece. By the time, I went to Lima to report that story for Harper’s, I’d been working with Nelson and Francisco and many of the other characters for three or four years.

2. The country where the novel is set is never named, nor is the city in which Nelson lives. The narrator also deliberately withholds the name of his hometown, calling it only T——. “I was born there, after all,” he says, “and though I left when I was only three, I suppose this fact gives me some right to call it whatever I please.” What led you to leave the country unnamed, and what leads the narrator to do the same with T——?

There’s a difference, of course, with leaving a setting unnamed, and leaving it vague or thinly described. Place is very important in my work, and leaving the country or the city unnamed is a choice. It gives me a certain freedom: I can create the contours of the city, or the countryside, create the details I need, the ones that best suit the story. The narrator has his own reason, and they have to do with protecting his family from any possible retribution (their proximity to the home of one of the novel’s villains is a central coincidence in the book).

Already I knew more about Nelson than I did about many of the people I’d grown up with, including dear friends, including even family members. I was coming close to deciphering some of the mystery around our one brief encounter, but there was something else too. It wasn’t so much what I’d learned, as how I’d learned it: Nelson’s secretes revealed to me by his confidantes, his loves, his classmates, people who’d seen fit to trust me, as if by sharing their various recollections, we could together accomplish something on his behalf. Re-create him. Reanimate him. Bring him back into the world.

3. The majority of the primary characters in the book, and many of the secondary ones, are either professional or aspiring actors. Nelson seems particularly talented, able to draw on disparate personal desires and to inhabit them. What about actors interests you to such an extent?

Acting is a skill that interests me a great deal, in part because I’m so bad at it. Who are the people who can throw themselves into a story in this way? Who can approach a story from such an intuitive place? But Nelson came first — his character, his unique brand of wandering, wheel-spinning. The acting came from him. I found that this profession suited his personality, and so I fell into the world of the theater. If there was a part of the preparation for writing this novel that I most enjoyed, it was reading plays, trying to understand the form. With every play I read, I felt like I was getting to understand Nelson better.

4. In anticipation of the Spanish version of your first novel, War by Candlelight, you wrote about your worry that “My incomplete knowledge of the place [Peru] will be on display.” In At Night We Walk in Circles, the narrator tends to bring in testimonials from other characters to support his claims, whether factual or what one might call moral. Did the apprehension you’d expressed as a Peruvian novelist who has spent most of his life in the United States factor into the narrator’s cautious construction of Nelson’s story?

I hadn’t thought of it that way, no. In fact, I don’t have those same anxieties anymore. I feel comfortable writing from this in-between place, about this imagined version of Peru. I’m an outsider in Lima, but an outsider with a great deal of access, and that allows me to see the strangeness of the place, and find its beauty.

5. The novel takes place after what Nelson’s father calls their home country’s “anxious years” — after the violence and after Diciembre’s heady radicalism seems to have petered out. The frequent foreshadowing keeps us conscious of the fact that the narrator is recalling the details of a past he dug up years ago. Why was it important that this be a story of return, or of reflection?

I have to wonder if I’m even qualified to answer this question. I know very little about why, in this case. It happened that way. It felt natural to write this voice, from this particular point of view, from this distance. I took a trip back in 1999, through Ayacucho and Huancavelica, and have some of these same memories; if not the details, the tone, the echoes rang true to me. It was also, I’d guess, an act of bravado — foreshadowing was a way of raising the stakes for myself, hinting at a resolution to events which I did not yet know how to resolve. In part, this is simply a way of reminding yourself to follow through with what your text is promising to deliver.

6. People are constantly asking the narrator what he’s doing, why he’s so intent on uncovering Nelson’s story — to the point that they become exasperated with him. Even Nelson, in their final conversation, tells him “I can’t understand why you’re here.” The narrator never seems to have an answer. Are you sometimes asked these kinds of questions by people who don’t understand your curiosity as a novelist or a journalist? Do you have an answer?

I have friends in Lima who poke fun at my obsession with prisons. I respond by poking fun at their obsession with chefs or opera singers. Curiosity is not about logic. I could answer this question a different way — give you, say, all the correct reasons for why prisons are an important topic, how they serve as a inverse reflection of the society we say we want to be. But my interest is much more visceral than that. The first time I walked into Lurigancho, I wanted desperately to understand everything about it. I still do. That’s always the germ of every piece of journalism I write. Any time I’ve done a story without that almost inexplicable curiosity — a curiosity that borders on obsession — the resulting piece has been a disappointment.