John R. Tunis’s “The Olympic Games” (1928)

Is it worth carrying on with the Olympics?

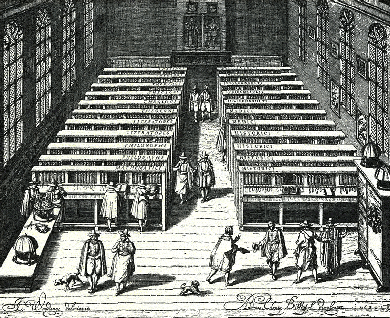

INTERIOR OF THE LIBRARY OF THE UNIVERSITY OF LEYDEN. From a print by Jan Cornelius Woudanus, dated 1610. Harper’s Magazine, April 1905

The XXII Winter Olympic Games open today in Sochi, Russia, amid concerns about Russia’s record on LGBT rights and human rights more generally and talk of “Potemkin toilets” and shower surveillance. In the face of all this Sochi-specific skepticism, we seem almost to have lost sight of our broader skepticism about the modern Olympics, which began as a celebration of international cooperation and the amateur spirit and have since become a spectacle of professionalism and consumerism. If so, this is too bad: a trip to the Harper’s Magazine archive suggests that raising such doubts is a sport nearly as old as the games themselves.

Although the 1924 Olympics included a week of winter-sport events that was retroactively labeled the first Winter Games, the first truly independent Winter Olympics were held in the Swiss town of St. Moritz, in 1928. This was also the year that the tradition of the Olympic Flame was introduced. It’s fair to say the modern Olympics were then in their infancy. Yet some people were already tiring of the spectacle. The August 1928 issue of Harper’s appeared just as the ninth Summer Games were beginning in Amsterdam, and in its pages John R. Tunis noted the increasing worry, throughout the international community, over “the advisability of continuing” the Games.

Tunis is known these days mostly as the author of a series of baseball novels for young boys. (They were childhood favorites of mine, and also of Philip Roth, who transferred his love of Tunis’s books to Nathan Zuckerman in American Pastoral.) But he was also one of the first great sports commentators and a frequent Harper’s contributor. In “The Olympic Games,” he gives a brief history of the original Olympics, which were central to ancient Greek culture for six hundred years until, Tunis argues, their spirit was destroyed by professionalism. “Indeed, so open and so apparent were the commercial recompenses dispensed,” Tunis writes, “that men like Plato and Socrates denounced them in public — doubtless receiving the same sort of derision as those who venture to question our sporting panorama of the twentieth century. Then, as now, a class came into existence which openly devoted its time to the serious business of athletics.” He goes on to suggest that the very changes that killed the original Olympics after seven centuries threatened to do the same to the modern games in less than half of one.

As a factual matter, of course, Tunis was wrong to doubt that the modern Games would survive. And not all of his complaints look legitimate in retrospect. (He believed that the inclusion of female athletes represented the “acme of absurdity.”) But his piece is well worth reading, if only as a reminder that the “golden age of amateurism” didn’t look like such a golden age at the time. It goes without saying that Tunis would have found the business that sports has since become about as familiar as Socrates would have found 1928 Amsterdam. In the interim, the Olympics have given up even the pretense of amateurism, which may be an improvement, since it at least saves us from a good deal of hypocrisy. As for global cooperation, the Sochi games seem already to be aggravating international tensions more than assuaging them. Like the 2008 Beijing Olympics, the Sochi Winter Games have many people asking whether serial human rights abusers ought to be given the opportunity to host this kind of global showcase. Perhaps the better question to ask about the Olympics is the one Tunis asked in the year the Winter Games began: whether “it would be best to drop them altogether.”