Matt Power: Headlamp a Must

“January 1998. In the windowless office shared by the Harper’s interns, I meet this hippie dude from Vermont: ponytail, spectacles of the sort favored by engineering students, lumberjack shirt.”

January 1998. In the windowless office shared by the Harper’s interns, I meet this hippie dude from Vermont: ponytail, spectacles of the sort favored by engineering students, lumberjack shirt. Matt Power. Others who’ve written remembrances of Matt have remarked on the poetry of his surname. In the spring of 1998, we treated it as if that were a thing — Matt power. If you had Matt power, you could recite entire episodes of The Simpsons by heart, along with passages from Moby-Dick. You could get yourself photographed by the New York Times while up a tree across from City Hall, wearing some sort of goofy sunflower headdress — some sort of goofy sunflower headdress and that goofy grin, goofy but also beautiful and disarming, scrolling upwards into impish fiddleheads at the corners.

If you had Matt power, you could take up with a bunch of squatters in a derelict building in the South Bronx, as Matt did the year after we met. For some reason, I’ve always pictured him camped out on the building’s roof, hanging his flannel underwear out to dry on a telephone wire, perhaps, or roasting a pigeon on a spit.

For all of his brainy bookishness and street smarts, Matt in the spring of 1998 was a greenhorn. We all were, but there was an innocence about him, some portion of which he never lost. I was only two years older, twenty-six to his twenty-four, which at the time seemed like a big difference and now seems like nothing. The other two interns in our cohort, Sarah Vos and Seth Ackerman, were younger still. Seth was, what, nineteen? The youngest intern Harper’s ever hired, I’m pretty sure. Young as he was, Seth could seem older than Matt, less innocent. Seth was precociously world-weary, whereas Matt would never weary of the world.

I’ll be honest, cooped up together in that windowless room day after day, Matt sometimes got on my nerves. Enough with The Simpsons already! Take a shower! See anyone else around here with a ponytail? In May, when our internship was nearing its end and we were all frantically hunting for jobs, I called Matt from another room and introduced myself as Peter Canby, director of The New Yorker’s fact-checking department, to which Matt had submitted a resumé, and he fell for it, my Peter Canby act. And afterwards, he grinned, a bit sheepishly, but he was crestfallen. I only remember that prank because years later, Matt would remind me, grinning and shaking his head, delighted now, “Remember when you pretended to be Peter Canby? Man, I totally fell for that.”

He fell for it not because he was gullible, I think, but because he believed unquestioningly that his talents were commensurate to his dreams. Why shouldn’t The New Yorker be calling? And he was right, his talents were commensurate to his dreams, which says something, considering the grand implausibility of his dreams.

“I have been thinking a lot about how we’d tease him in those days,” Seth wrote me recently. “Didn’t we always tease him about Moby-Dick somehow? Was it because he was obsessed with the book or something? Can’t remember. In any case, maybe that’s what implanted a certain future book title in your brain.” Seth’s right that Matt loved Moby-Dick, and I think it was through our shared enthusiasm for certain writers — Melville, Frazier, Matthiessen, Lopez, McPhee, a list we kept adding to over the years — that Matt and I went from internship to friendship.

As it happens, this week, I’m teaching The Songlines by Bruce Chatwin, a writer I first read at Matt’s recommendation, and rereading the book, which is at its heart an essay on “the nature of human restlessness,” I keep thinking of Matt, who was much more Chatwin’s literary heir than I ever could be. Paraphrasing Pascal, Chatwin asks, Why “must a man with sufficient to live on feel drawn to divert himself on long sea voyages? To dwell in another town? To go off in search of a peppercorn?” I would like to know Matt’s answer.

Since his death, people have been asking me if Matt and I were close, and I don’t hesitate to say yes, but our closeness was more a matter of time than place; it was the closeness of accumulated history. I never lived in Brooklyn, so I visited the house on Hawthorne Street less often than other friends of Matt and his wife, Jess. He and I were close because we’d set out together with a sense of common purpose. We’d known each other when we were both lowly greenhorn interns and when our careers as writers were still fantasies, and then slowly, arduously, luckily, separately but in tandem, competing with each other and cheering each other on, we’d acted those fantasies out and made them real. I never traveled with Matt on one of his expeditions, but since meeting him in 1998, I’ve always felt that I was traveling with him on the grand adventure of our lives.

A scientist I once wrote about told me that there are two kinds of oceanographers: Those who go to sea and those who go to the lab. The same tends to be true of writers. Matt was unambiguously the former sort, and for a long while, I suspected I was doomed to be the latter. I reconciled myself to the editorial office and the classroom, enviously following Matt’s seafaring from afar. While he was motorcycling in Kashmir, I was in Ann Arbor earning an MFA in poetry. We had the occasional drink, saw each other every year at the Harper’s Christmas party, read each other’s work when it appeared in print. We shared friends, an agent, an editor. We shared an abiding love of this magazine, which had been for both of us, as it has for many other writers and editors over the years, what the Pequod was for Ishmael: our Harvard and our Yale.

In 2007, during my last semester as a high school English teacher, I emailed Matt to invite him to visit my twelfth-grade literary journalism course. “Greetings from the Galapagos,” he replied. “I’m here working on a couple of stories (just sailed across from panama), and am flying tomorrow to Quito for a week and then back to NYC on the 18th. I’d be delighted to talk to your class.” He came on a spring afternoon in early May. Having long since lost the ponytail and traded the woodsman’s getup for a blazer of chestnut suede, face tan from his voyage to the Galapagos and grizzled with a day or two of stubble, he cut a dashing figure.

He’d recently published what remains one of my favorites pieces of his, “The Magic Mountain: Trickle-down economics in a Philippine garbage dump,” and I’d assigned it to my students. The subtitle suggests to readers that we may be in for a dreary trip. We are, and we aren’t. There’s a reason — other than a weakness for literary allusions on the part of Harper’s editors — that the word magic appears in the title. Matt was an alchemist.

He begins in a traffic jam in Quezon, on his way to Payatas, a fifty-acre dumpsite where, in July 2000, torrential rains set off an avalanche that buried alive the inhabitants of a shantytown who’d eked out something approaching a living by scavenging in the trash heap that buried them. Throughout his opening section, Matt makes the colossal landfill loom, the way the whale does in the opening chapter of Moby-Dick, building to this crescendo of images:

As we come over a rise, my first glimpse of Payatas is hallucinatory: a great smoky-gray mass that towers above the trees and shanties creeping up to its edge. On the rounded summit, almost the same color as the thunderheads that mass over the city in the afternoons, a tiny backhoe crawls along a contour, seeming to float in the sky. As we approach, shapes and colors emerge out of the gray. What at first seemed to be flocks of seagulls spiraling upward in a hot wind reveal themselves to be cyclones of plastic bags. The huge hill itself appears to shimmer in the heat, and then its surface resolves into a moving mass of people, hundreds of them, scuttling like termites over a mound. From this distance, with the wind blowing the other way, Payatas displays a terrible beauty, inspiring an amoral wonder at the sheer scale and collective will that built it, over many years, from the accumulated detritus of millions of lives.

A terrible beauty — the phrase captures so much of what Matt wrote.

Also characteristic of what he wrote is the way he refuses to let those people remain “a moving mass.” Another passage:

We walk across a narrow bamboo bridge and up a steep hill, where a group of people — mothers with babies, men with arms crossed — sit in the shade of a military-style tent, in which a cooking class is under way. At the foot of the hill lies a half-acre of vegetables: beautifully tended rows of lettuce, tomatoes, carrots, squash, corn. A few people rest under a giant star-apple tree by a small creek. A pregnant woman with a little boy works her way down a row of tomato plants, pulling weeds. Tropical butterflies flit about. It would be an utterly rural and bucolic scene if it weren’t for the rusty jumble of houses that begin at the field’s edge, towered over by the gray hill of Payatas. The rumble of the bull-dozers and the trucks circling the road up its side is a dull grind, and periodically a plastic bag caught in an updraft drifts toward us and descends, delicate as a floating dandelion seed, into the branches of the trees.

There is so much about this passage that I admire, but above all what I love is how it brings together — or rather, keeps together — the natural and the human. They are inseparable, Matt knew. These few sentences, mostly descriptive, imply a philosophy, one that can register the resemblance between a plastic bag and a dandelion seed, one that can discover a garden in a wasteland, one that can reconcile that grin of his with the sense, as he wrote in “Holy Soul,” that “at the core of life” is “sorrow and transience.”

In my classroom on the afternoon that Matt visited was a student who would go on to become a reporter for the New York Times, and on the day I learned of Matt’s death, this former student sent me a message about “The Magic Mountain.” He wrote: “Remembering fondly the ‘constellation fallen to earth’ line you flagged for us, what, 8 years ago? What a kicker.” I knew the line he was talking about, from the closing paragraph:

At the open window the equatorial darkness falls like a curtain, and across the creek the mountain of the dumpsite rears black beneath a net of stars. Against the silhouette of the garbage mountain, a faint line of lights works its way upward. They are the homemade headlamps of the night shift tracing their way up the pile. Reaching the top, they spread themselves out, shining their lights on the shifting ground to begin their search. Beneath the wide night sky those tiny human sparks split and rearrange, like a constellation fallen to earth, as if uncertain of what hopeful legend they are meant to invoke.

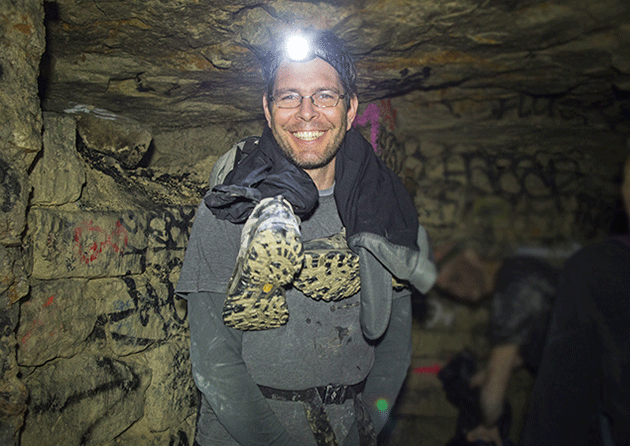

Rereading that passage today, I find it hard not to think of all the pictures of Matt wearing a headlamp, as if he were among those fallen stars, those tiny human sparks, uncertain of the legend he meant to invoke but certain somehow that it was a hopeful one.

Shortly after Matt visited my class, I stopped teaching high school English and set out to become, like him, the sort of writer who goes to sea. (He and Jess would later spend a year in Ann Arbor on a Knight-Wallace Fellowship — Matt’s answer to an MFA.) In 2010, back in the “insular city of the Manhattoes,” once again pent up in lath and plaster, clinched to a desk, I would become Matt’s editor, first at Harper’s, then at GQ, and that experience drew us closer still. At its best, the relationship between writer and editor is deeply intimate, akin to that between athlete and coach, or actor and director. Although I left GQ — and editing — before he finished it, the last piece I assigned to Matt was the one about urban explorers, and when he told me of his plan to go mountaineering on Notre Dame, I said to him something like, Please be careful, don’t do anything stupid, feeling that his life was in my hands while also hoping, as editors do, that he would pull it off, because how great would that be? A scene from atop Notre Dame?

In the months before he died, I was preparing to go to sea once again. I’d moved back to Ann Arbor, where I’d discovered that, during their year here, as in Brooklyn, as in every place they went together, Matt and Jess had gathered around them a constellation. We had even more friends in common than before, and more places we loved in common. We emailed each other often, and whenever I returned to New York, I could count on a drink with Matt. I think his thoughts, increasingly, were turning toward shore. In his emails, the dreams he shared were more sedentary than those he’d shared in the spring of 1998.

In our last conversation, conducted by email but at the pace of conversation, a few weeks before his death, we talked about book projects. I had a notion of how he could turn one of his Harper’s stories, “Mississippi Drift,” into a book. “This is the tricky part,” I concluded my message. “You spend at least a couple of reclusive years saying no to magazine assignments unless they’re somehow related so you can write the fucker.” And he wrote back: “Well, next time you’re in town, the whiskey’s on me and we can hash out the details.”

When I was first preparing to go to sea, I emailed Matt, asking for gear recommendations. He sent me an excellent packing list, which I’m now passing on to anyone else who wishes to go off in search of a peppercorn. His last piece of advice is the most essential:

hey Donovan,

a few things I’ve found indispensible:

Pelican laptop case. www.pelican.com Rock solid, waterproof, dustproof, padded on the inside. War correspondent’s choice. It’s heavy and expensive, but it’s a tank.

A digital flash recorder. Great for interviews. You can download directly into a computer. You can alter the playback speed so you can transcribe while you type. 12 hours recording time. About a hundred bucks. If you’re recording a lot of interviews, I would absolutely get one.

A good umbrella is probably the most useful thing in the world, even when trekking. Golite makes some awesome sturdy and lightweight travel umbrellas.

a leatherman multitool is great.

A universal adapter (switches between pretty much every bizarro form of outlet in the world.)

An LED headlamp (petzl and black diamond make great ones) is a must.

Cotton kills. You want layers of things like capilene and fleece with a good raincoat. My understanding is that goretex does not work in alaska, so you might need a proper maritime foul weather raincoat if you are going to be out on a boat in the bering strait or something.

Dramamine, bonine, ambien and a wide assortment of headache pills are always nice for plane trips/boat trips.

Walther PPK 9mm with hollowpoint rounds. Because you never know. Or if you really want that grizzly-stopping power, .357 and higher.

Bullwhip and fedora optional.

Keeping all this in mind, traveling light is nice.

Stay hydrated, I’ll send more thoughts as they come along.

yrs

Matt

In penance for having teased him those many years ago, I’ll end by doing what he might have done those many years ago — quote Melville:

Terrors of the terrible! Is all this agony so vain? Take heart, take heart, O Bulkington! Bear thee grimly, demigod! Up from the spray of thy ocean-perishing — straight up, leaps thy apotheosis!