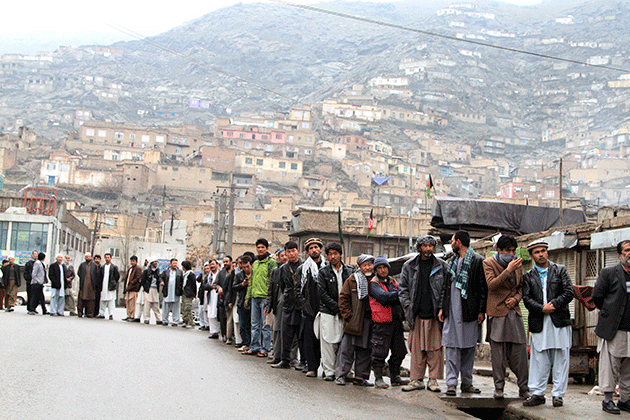

Afghan men line up outside a polling station to cast their ballots in Kabul, Afghanistan, Saturday, April 5, 2014. © AP Photo/Rahmatullah Nikzad

On Saturday, as my family was getting ready to vote in Afghanistan’s presidential and provincial-council elections, my father made a request of a kind I hadn’t heard since Eid. “Spread yourselves out to different polling centers,” he said, concerned about the sorts of suicide bombings that have killed entire families in the past. “Don’t go together.”

The Taliban’s recent attacks across Afghanistan, along with bad memories of the fraud-ridden 2009 elections, had made for gloomy headlines in the international press ahead of last weekend’s vote. “Return of the Taliban,” ran Time magazine’s April 14 cover line. “[I]ncoming planes are half empty,” reported the New York Times, noting that international observers, usually a fixture of elections here, were keeping their distance. Among many Afghans, however, the Taliban’s stepped-up pre-election violence — particularly their murder last month of children and civilians in a Kabul hotel — had triggered a sense of defiance.

Before the polls opened, it was hard to gauge the strength of that defiance. A tremendous security presence — the government brought out everything it had, including trainees from the military academy — promised safety, but it might equally have scared people into staying home. Reports from the southern city of Kandahar, hard-hit with violence back in 2009, told of abandoned streets. But soon broadcast and social media were flooded with images of crowded voting facilities. In one photograph, women waited in line with plastic sheets held over their heads against the rain; in another, two children led their blind father into a polling station. Many Afghans, it seemed, had braved it all to vote.

I was the last in my family to cast a ballot. I stayed home for the first part of the day, watching the news on television and waiting for the others to return. My mother, who walks with the help of a cane on rainy days, went to pick up my grandmother so they could vote together. She realized when she got to the polling place that she’d forgotten her glasses. “It was easy to vote for a presidential candidate,” she said. The ballot had only eleven names on it, and three of the candidates had pulled out of the race before Election Day. “But the provincial council — I struggled to find who I wanted to vote for.” My mother searched for the name of a woman whose television ads had made an impression on her, but there were 457 candidates listed on the multipage ballot. After a few minutes she gave up and ticked the box next to the first woman she saw. “You’ll be party to any sin she commits,” my father joked over lunch.

When my turn came, I had two options: I could vote at the school I attended as a child or at the mosque where I pray on Fridays. I chose the mosque, which is closer to home, because the skies were dark with rain clouds. The line along the mosque wall was orderly. Behind me was a green-eyed old man who, along with his daughters, had tried two other polling stations before arriving here. Within forty-five minutes I’d made it to the mosque entrance, where I took off my sandals and submitted to a police pat-down. Inside, a handful of observers, some of them crouching against stone columns, watched the voters file in. An election worker checked my I.D. card and punched a hole in it, then examined my hands for signs that I’d already voted. Satisfied that I hadn’t, he cleaned my right index finger with a damp cloth and dipped it in a bottle of blue ink. Then he sprayed my thumb with a transparent liquid visible only under a UV flashlight. I took my two ballots and walked into a booth. Five minutes after entering the mosque, I was finished.

As I walked out, feeling the elation of a first-time voter, I discovered that my sandals were gone. The mosque’s muezzin, who was serving as a poll worker that day, loaned me his. “They should put up a sign explaining that it’s Election Day, not Friday prayer,” joked my brother, referring to the tendency of shoes — particularly nice shoes — to go missing at the mosque.

By the end of the day, after voting had been extended for an hour nationwide and extra ballots had been delivered to several provinces, between 7 and 7.5 million Afghans, approximately 60 percent of those eligible, had reportedly voted. “The Day of Blue Fingers,” read a headline in Afghanistan’s largest private newspaper, Hasht-e-Subh. “The moment fingers triumphed over fists,” the Afghan poet Abdul Samay Hamed was quoted as saying. The Interior Ministry had recorded 140 attacks or attempted attacks across the country, and in parts of rural Afghanistan (and even some districts very close to Kabul), the Taliban had spread threatening leaflets the night before, keeping voter turnout low, but there had been no dramatic lapses in security.

The counting of ballots began immediately after polling was closed. In the two centers I visited in northern Kabul, observers watched closely as election workers sorted the ballots into stacks, one for each candidate. One ballot I saw, clearly a protest vote, had a line drawn through all the names. In the morning, a tally of votes was taped to the door of each polling center.

In the two days since the vote, practically every Afghan on social media has become an amateur data analyst, posting graphs and charts with numbers and percentages from across the country, with some giving their favorite candidate as much as 90 percent of the vote in certain provinces. Videos and photographs of alleged fraud have also been circulating. Nevertheless, a sense of optimism persists, a renewed belief in the still fragile democratic process and a faith in the young security forces charged with protecting Afghanistan as foreign troops withdraw. It is a cautious optimism, though, dampened by the fear of another lengthy post-polling process in which candidates will bicker over the results.