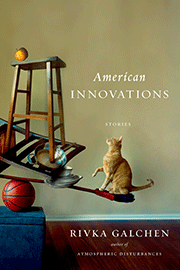

The characters in Rivka Galchen’s new collection, American Innovations, are as surprised and confused by time travel, mysterious growths, and encounters with the dead as they are by being unemployed, getting divorced, and falling in love. In “Once an Empire,” which was published in the February 2010 issue of Harper’s Magazine, a woman arrives home to find her furniture climbing down the fire escape. Other stories revisit such classics as Thurber’s “The Secret Life of Walter Mitty” and Borges’s “The Aleph,” but consider them all from the perspectives of women. In each story, Galchen creates a world at once recognizable but disturbed, uncertain yet comforting.

Galchen’s first novel, Atmospheric Disturbances, was published in 2008. She is a recipient of the William Saroyan International Prize for Fiction Writing and a Rona Jaffe Foundation Writers’ Award. She has also written for Harper’s about Handel’s Messiah, hurricanes, and the Argentinean writer César Aira. I wrote to her with six questions.

1. In “The Entire North Side Was Covered with Fire,” you describe “Prison bars of not-money” growing around the narrator “like wild magic corn.” It seemed to me that many of the characters in American Innovations are concerned about money or work, and I notice that the first of the ten stories was published in 2008. Is this a book of Great Recession stories?

I hadn’t thought of it that way, but it’s an interesting point. I think most people worry about money in one way or another quite often, maybe most of the time, but maybe this is heightened by absorbing as a kind of pollen from the zeitgeist a sense that the today of things is not the tomorrow of things. No one wants to slide down the socioeconomic ladder, and the majority of my narrators have chosen jobs that aren’t really coming with pension plans, yet I’m not sure if that fully explains the sensitivity to cost that many but not all of them have. Money is a taboo; people have weird mystical irrational rituals around nearly every aspect of it.

2. The stories in the collection are described on the jacket as “canonical stories re-imagined from the perspective of female characters.” “The Lost Order,” for example, echoes James Thurber’s “The Secret Life of Walter Mitty.” How did having a female narrator influence the reshaping of this story?

Not in the way I had expected. I had long had a little joke with myself, when I would find myself persecuted with boring thoughts about my appearance or what someone thought of me, I would think: The Secret Life of Willa Mitty. The idea was that Walter Mitty is having a dull day, sure, but at least in his mind he’s a wildly heroic figure, a fighter pilot or a dashing surgeon. He basically has the kinds of fantasies that the culture supplies to men, about what it might mean to be manly, which is problematic, sure, but it just seemed a lot more buoying than the fantasies out there for women . . .

So I think I thought the story would pay close attention to what kinds of inner dream spaces are suggested to women, and then see where that led me . . . that that would form a perverse mirror to the Walter Mitty story . . . but then the story didn’t go that way! It was almost as if the story and the character were both rejecting my weak idea and pushed me around, made me co-opt that space of being a fantasist of a certain kind, of a male kind, and then find out how it comes to fisticuffs with reality. I often when I’m stuck with a story proceed in that way, proceed by thinking: how can I uncover what was wrong in the thinking that brought me this far? And then things turn, and briefly give off light.

3. Do you think of the narrator as being the same person, though at different moments in her life, in each story?

Hmm. I think they’d all be kept in the same part of the zoo, that’s for sure, but I definitely think of them as different people.

4. The narrator’s unreliability — the narrator lies or conceals information, or the account suddenly turns surreal — is common both to these stories and to your novel, Atmospheric Disturbances, in which the main character is a delusional psychiatrist. How does this unreliability play out differently in short fiction, as compared with a novel?

That’s tricky, the unreliability thing, which is in so many ways just a synonym for a first-person narrator, but I get what you’re talking about — there are narrators you would take directions to the subway from, and others maybe less so. But there’s always this ironic gap, between what a character knows and the additional knowledge the reader feels they have over the character — the don’t-do-it-Oedipus-she’s-your-mother feeling — and this gap can be accordioned, and that weird polka-music sound is actually a major mechanism of literature I think. Maybe this means the short story is a kind of two-minute chicken-dance polka? But what does that leave a novel as? I guess it exposes the brick wall of metaphor.

From “American Innovations”:

My hand moved to the mass. The mass liked being touched. I lifted my shirt. I would say what I saw was a wow. Even though it was modest, maybe a B cup in size. It didn’t need support. It manifested all the expected anatomy, the detailing of which I feel is private. What I saw was really textbook. Safe for its location, there on my back. As if to hide from me. Or as if to discreetly maintain an unacknowledged child. Though the discreetness would work only in a world in which we meet one another exclusively head-on, or possibly in three-quarters profile. Because in profile the anatomy really could not be denied.

I pulled my shirt back down. It was fitted but, thankfully, long.

5. In the title story, the narrator finds that she has suddenly grown a breast on her lower back. Surreal twists are common in these stories — what is the appeal of the surreal, for you?

It’s pretty much always about emotional realism. This idea that sometimes the straight facts occlude the truth, instead of reveal it. For example, I think if a story was, say, about a woman who because she was flat-chested or overweight or whatever, felt that her body was unacceptable and deformed but had made her peace with that, then came across what other people were saying about her body . . . well, I’m pretty sure we’d all just sigh and not read that story or feel like we were stuck at the dentist office reading articles about people whining.

I felt like the surreal gave a chance in this story to see something that is so ubiquitous, so common, that it’s invisible to us. Even if we read about it and talk about it, we’re not actually in touch with it. Not that that’s what the story is about! But it isn’t not about that either.

6. Has teaching in the MFA program at Columbia influenced your writing, or the way you think about literature?

I only ever teach seminars, usually a fiction seminar in the fall and a nonfiction one in the spring. I recognize that I’m supposed to feel enervated and depressed about teaching, but I don’t. I love the pressure of having to think very seriously about a book, and then to get to talk about it with other people who have, for the most part, also thought seriously about the book. How often does it happen in everyday life that our friends or acquaintances have read the same books as us, and then we think about them together? It’s much easier in a social setting to find common ground in talking about movies or TV. So I guess the main way teaching influences the way I think about literature is that it enables me to think more about literature.