“The mysterious throbbing of the life that is inner and under.” That, by her account, was what most interested Sara Jeannette Duncan. Yet she wrote mostly about manners. For her surface was depth. You can see it in the opening lines of “The Ordination of Asoka,” published in Harper’s Magazine in 1903: “My invitation came from Oo-Dhamma-Nanda. That was his name ‘in religion.’ ” Almost a complete story unto itself. An invitation, a stranger who is not what he seems, the gentle mockery of pretension.

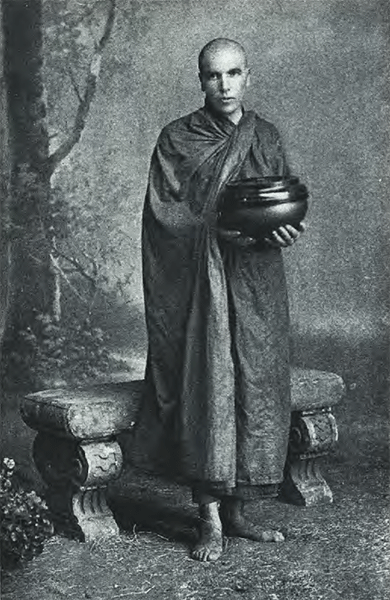

But Oo-Dhamma-Nanda, an Irishman ordained as a Buddhist monk at a time when such a conversion was still remarkable enough to justify a magazine story, was not pretending. “Yes,” Duncan reflects, “he was like them.” Them — the story is racist, alert to imaginary distinctions between “one’s own race” and the Burmese, bemused, too, by the “spiritualized” Irishness of Oo-Dhamma-Nanda. Duncan herself was a Canadian, married to an Englishman — she published the piece as Mrs. Everard Cotes, wife of a man identified in the story only as “the Stoic” — living in India, her reputation made by an autobiographical novel called An American Girl in London. She got her start in New Orleans, rose at the Washington Post, and is remembered now, if at all, for a satirical novel of provincial Ontario life called The Imperialist, a story of the world she’d left behind. She understood displacement, reinvention, and the undercurrents that carry the past into the present. She could be cruel and funny and forgiving at the same time. “Nearly as good as ‘Mark Twain,’ ” noted a contemporary critic. Sometimes better.

Henry James, whom she considered a peer, did not get the joke. Her writing, he told her, lacked the “bony structure and palpable, as it were, tense cord” that would result in a necessary “direction and march of the subject.” She lingered too long in that “mysterious throbbing.” No surprise to James: “It’s the frequent fault of women’s work,” he consoled.

It’s also why I’ve included Duncan’s “Asoka” rather than a piece of James’s rigidly certain American Scene, published two years later. In his nonfiction, James knew what he knew and marched his prose along accordingly. Not so Duncan, whose empathy surpasses her sarcasm and undermines her bigotry. “What I longed to get some inkling of,” she writes of the Irishman, “was whether through mysticism and mortification he had really attained, even momentarily, another plane of existence.”

No mystic herself, she could only observe. The result is a small comedy of manners, in which “the inner and the under” are hinted at but never fully revealed. That’s the subtle trick of the story: Mrs. Everard Cotes knew what she could not know.