Introducing the October 2014 Issue

Rebecca Solnit on silencing women, a Marine commander returns to Iraq, the decline of PBS, and more

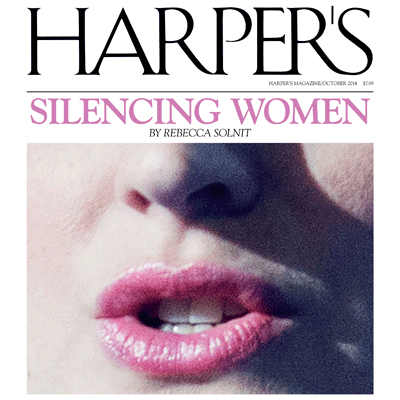

The word “hysteria,” as Rebecca Solnit notes in the cover story of our October 2014 issue, comes from the Greek for “uterus,” and it has been used to undermine the stories told by women since the late nineteenth century, when Sigmund Freud dismissed the sufferings of his “hysterical” female patients and effectively stopped listening to them. Since then, things have changed less than we might think. When today’s women criticize men—especially powerful men, or even established institutions run by men—they are routinely condemned as “delusional, confused, manipulative, malicious,” called out as “sluts” and “prostitutes,” and told to keep their mouths shut. Particularly intolerable, it seems, is when women speak out on sexual matters. One need only remember Anita Hill, who was roundly humiliated by the Senate Judiciary Committee during Clarence Thomas’s 1991 Supreme Court confirmation hearing. Solnit argues that women’s voices must not be silenced by critics who resort to this ancient and utterly defunct “framework of feminine mendacity and murky-mindedness.”

News about Iraq never seems to stop. In this month’s Folio, Benjamin Busch revisits the country he “invaded” as a Marine commander in 2004. Back then, he saw a certain cautious optimism among the Iraqis, which has long since vanished. Instead, they now assume that tomorrow will be worse than today—and apparently they are right. In a moving portrait of contemporary Iraq, Busch details the despair that seems to be prevalent now that the Americans have left. He wonders, too, whether the sectarian and political meltdown of the country may be an omen of what is to come in Afghanistan when the American army departs.

In “PBS Self-Destructs,” Eugenia Williamson chronicles the history of mission creep (as the military men like to say) at the Public Broadcasting System. Conceived in 1967 as a Great Society initiative, the network was supposed to level the effects of poverty by closing the education gap—meanwhile proving to the world that Americans, in Lyndon Johnson’s words, “want most of all to enrich man’s spirit.” It soon became clear, however, that a truly independent network might be critical of the very officials who funded it. And Richard Nixon, who in any case regarded PBS as a conclave of Ivy League snobs, threatened to destroy it—thus beginning the network’s traditional role as a political football and election-year whipping boy. In a thoroughly reported and frequently funny piece, Williamson brings us all the way to the present day, detailing the network’s chummy relationship with its corporate sponsors and its Anglophile determination to transform itself into (in the words of one PBS executive) “premium television on the honors system.”

In 2013, some 8,000 U.S. veterans committed suicide—nearly one an hour for an entire year. Clearly PTSD, which has existed at least as long as modern warfare, has reached epidemic proportions in this country. In “You Are Not Alone Across Time,” contributing editor Wyatt Mason describes how the armed forces are experimenting with a novel remedy for the disorder: performances of ancient Greek tragedies like Ajax and Philoctetes. Mason follows theater director and translator Bryan Doerries as he travels from base to base teaching soldiers the lessons that Sophocles taught to Athens more than two millennia ago. Since the program started, Doerries has gotten actors such as Adam Driver, Paul Giamatti, and Jesse Eisenberg to join him on his mission, and to expand it to other communities in need.

Also in this issue: Portraits of lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender South Africans by photographer Zanele Muholi; Rivka Galchen on Haruki Murakami’s Colorless Tsukuru Tazaki and His Years of Pilgrimage; Jenny Turner on Elena Ferrante’s perceptive and sardonic fiction; and a new story by Robert Boswell.