Introducing the March Issue

Esther Kaplan investigates workplace spying, Leslie Jamison ponders the allure of life after death, John Crowley discusses what it means to be well read, and more

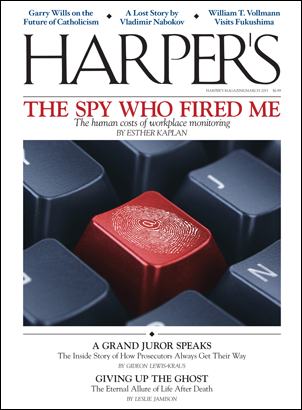

Last Thursday, Amy Pascal announced she would be stepping down as co-chairperson of Sony Pictures Entertainment. Few in the industry were surprised by her departure. In late 2014, North Korean hackers carried out a devastating cyberattack against Sony, releasing films, passwords, and a trove of embarrassing personal emails sent by company executives. In one exchange, Pascal and producer Scott Rudin joked that President Obama prefers films starring black actors, such as The Butler and 12 Years a Slave. “This was a private communication that was stolen,” she said in her apology; but the damage was done. As Esther Kaplan reveals in this month’s cover feature, “The Spy Who Fired Me,” stories like Pascal’s are more common now than ever before. “Every aspect of an office worker’s life can now be measured,” she writes, “and an increasing number of corporations and institutions . . . are using that information to make hiring and firing decisions.” Kaplan sees these data-collecting practices as a “high-tech effort to squeeze every last drop of productivity from corporate workforces, an effort that pushes employees to their mental, emotional, and physical limits; claims control over their working and nonworking hours; and compensates them as little as possible, even at the risk of violating labor laws.” After talking to UPS drivers, servers at Starbucks and McDonald’s, retail sales staff, and freelance transcriptionists, Kaplan arrives at an uncomfortable conclusion: Employers are becoming menacing Big Brothers, while employees become cringing Winston Smiths.

Last Thursday, Amy Pascal announced she would be stepping down as co-chairperson of Sony Pictures Entertainment. Few in the industry were surprised by her departure. In late 2014, North Korean hackers carried out a devastating cyberattack against Sony, releasing films, passwords, and a trove of embarrassing personal emails sent by company executives. In one exchange, Pascal and producer Scott Rudin joked that President Obama prefers films starring black actors, such as The Butler and 12 Years a Slave. “This was a private communication that was stolen,” she said in her apology; but the damage was done. As Esther Kaplan reveals in this month’s cover feature, “The Spy Who Fired Me,” stories like Pascal’s are more common now than ever before. “Every aspect of an office worker’s life can now be measured,” she writes, “and an increasing number of corporations and institutions . . . are using that information to make hiring and firing decisions.” Kaplan sees these data-collecting practices as a “high-tech effort to squeeze every last drop of productivity from corporate workforces, an effort that pushes employees to their mental, emotional, and physical limits; claims control over their working and nonworking hours; and compensates them as little as possible, even at the risk of violating labor laws.” After talking to UPS drivers, servers at Starbucks and McDonald’s, retail sales staff, and freelance transcriptionists, Kaplan arrives at an uncomfortable conclusion: Employers are becoming menacing Big Brothers, while employees become cringing Winston Smiths.

In his essay about serving on a New York State grand jury, Gideon Lewis-Kraus investigates why prosecutors almost always get their way. Over the course of sixty hours of service, during which Lewis-Kraus voted on more than a hundred cases, the jury failed to return an indictment only once. “We were simply not expected to dismiss charges,” he writes. As we saw when grand juries in New York and St. Louis refused to indict the police officers who killed Michael Brown and Eric Garner, indictment is not inevitable. Rather, as Lewis-Kraus writes, the issue is that, “no case is mounted by the defense; the state’s version of events is the only story on offer. As I saw firsthand, this makes the prosecutors singularly powerful narrators.”

In “Giving Up the Ghost,” Leslie Jamison examines the work of Jim Tucker, a child psychiatrist at the University of Virginia who has spent the last fourteen years tracking “children who have reported memories of prior lives.” Tucker has identified 2,078 such cases, among them that of a two-year-old boy who claimed to have been a fighter pilot shot down by the Japanese. “Airplane crash! Plane on fire! Little man can’t get out!” the boy would repeatedly say. Jamison muses: “Stories about past lives help explain this life—they promise a root structure beneath the inexplicable soil of what we see and live and know, what we offer one another.”

In his Letter From Japan, William T. Vollmann heads to Fukushima, where, four years ago, an earthquake caused a containment breach at Nuclear Plant No. 1. He finds those living on the edge of the 2011 exclusion zone surprisingly blasé about the potential dangers of lingering radiation. “It has no reality,” a cab driver from Iwaki tells him. “If someone around here got cancer, I might feel something, but it’s invisible, so I don’t feel anything.” Vollmann himself is less sanguine, noting the quiet horror and sadness in Tomioka, a town partly inside the forbidden zone surrounding the plant. “I ask you,” he writes, “to imagine yourself looking at a certain weed-grown wooden residence with unswept snow on the front porch as the interpreter points and says: ‘This must have been a very nice house. The owner must have been very proud.’ ”

Our March Readings includes an excerpt from David Graeber’s book The Utopia of Rules, an examination of endlessly metastasizing bureaucracy (“Any market reform or government initiative intended to reduce red tape and promote market forces will ultimately increase the number of regulations and bureaucrats”). The section continues with a dispatch from a furry convention (“Many wore accessories: a parasol, suspenders, Clubmaster glasses, balloons. One appeared to be channeling Nineties grunge, with a flannel shirt and Fender Stratocaster”) and a selection from Nell Zink’s new novel, Mislaid, which will be published by Ecco in May.

Also in this issue: John Crowley discusses what it means to call yourself well read; Rivka Galchen reviews Paddington: The Movie; and Adam Hochschild recounts his role in revealing that, in the decades after World War II, the National Student Association was funded by the CIA.