Introducing the April Issue

Fenton Johnson ponders the dignity of solitude, Andrew Cockburn investigates the incompetence of Citigroup, Rebecca Solnit argues that high school should be abolished, and more

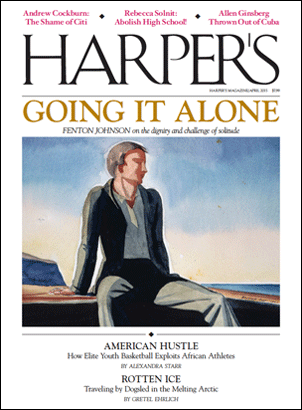

On Monday, March 9, Chris Soules, a farmer from small-town Iowa, proposed to Whitney Bischoff, a Chicago-based fertility nurse, on primetime television. Their engagement marked the finale of ABC’s The Bachelor, a dating reality show that averaged over eight million viewers per episode during its nineteenth season. The enduring popularity of The Bachelor and programs of its ilk—The Bachelorette, Millionaire Matchmaker—which assume that coupling up is so desirable that one would risk televised humiliation in pursuit of a mate, made me grateful for this month’s cover story, “Going It Alone.” Fenton Johnson’s Folio is an elegant meditation on those who live a life of solitude. Johnson’s solitaries are not sad singletons or romantic failures; rather, they are individuals for whom “solitude and silence are positive gestures.” “Bachelorhood is a legitimate vocation,” he writes. “Spinsterhood is a calling, a destiny.” Both states provide the opportunity to “encounter the great silence at the core of being, a silence that is both uniquely [one’s own] and one with the background hum of the universe.” If this encounter is often fraught, even painful, then so be it. “The path to liberation,” Johnson reminds us, “runs through suffering.”

On Monday, March 9, Chris Soules, a farmer from small-town Iowa, proposed to Whitney Bischoff, a Chicago-based fertility nurse, on primetime television. Their engagement marked the finale of ABC’s The Bachelor, a dating reality show that averaged over eight million viewers per episode during its nineteenth season. The enduring popularity of The Bachelor and programs of its ilk—The Bachelorette, Millionaire Matchmaker—which assume that coupling up is so desirable that one would risk televised humiliation in pursuit of a mate, made me grateful for this month’s cover story, “Going It Alone.” Fenton Johnson’s Folio is an elegant meditation on those who live a life of solitude. Johnson’s solitaries are not sad singletons or romantic failures; rather, they are individuals for whom “solitude and silence are positive gestures.” “Bachelorhood is a legitimate vocation,” he writes. “Spinsterhood is a calling, a destiny.” Both states provide the opportunity to “encounter the great silence at the core of being, a silence that is both uniquely [one’s own] and one with the background hum of the universe.” If this encounter is often fraught, even painful, then so be it. “The path to liberation,” Johnson reminds us, “runs through suffering.”

Rebecca Solnit did not attend high school, a fact that she calls, in this month’s Easy Chair, “one of my proudest accomplishments and one of my greatest escapes.” After a traumatic year of middle school, Solnit skipped the eighth grade and spent the next two years at an alternative junior high, where she mingled with “hard-partying teenage girls who dated adult drug dealers, boys who reeked of pot smoke, and other misfits like me.” At the age of fifteen, she passed the G.E.D. test and enrolled at a local community college. “High school is often considered a definitive American experience,” Solnit writes, “one that can define who you are, for better or worse, for the rest of your life.” But she wonders whether it is in fact necessary—especially given how painful those four years can be. “Eight percent of high school students have attempted to kill themselves,” she notes. “That’s a lot of people crying out for something to change.”

Gretel Ehrlich’s Letter from Greenland is blunt and terrifying. “The news from the Ice Desk,” she reports, “is this: the prognosis for the future of Arctic ice, and thus for human life on the planet, is grim.” Ehrlich, who has been traveling to Greenland since 1993, has witnessed firsthand the devastation wrought by rising temperatures. At the moment, Inuit hunters are those most directly affected: it’s dangerous to follow walrus, ring seals, and polar bears—on which the hunters rely for food—across increasingly precarious sea ice. But, as Ehrlich reminds us, “what happens at the top of the world affects us all.”

In the aftermath of 9/11, Abdul Nasser Khantumani and his son Muhammed, who was seventeen at the time, were arrested in Pakistan. In early 2002, they were transferred to the newly opened detention camp at the Guantánamo Bay Naval Base, in Cuba, where they remained until 2009, when the Obama Administration determined that neither posed a risk to national security. In this month’s Report, Pardiss Kebriaei, the lawyer for both father and son since 2008, recounts, in painful detail, the ordeals both have suffered since their detention: forced separation, solitary confinement, and torture (Muhammed’s nose was broken by Pakistani interrogators; Abdul Nasser’s forehead was fractured by a guard in an American-run prison in Afghanistan). Kebriaei reveals that, despite the fact that the Khantumanis have been released from Guantánamo, their troubles are far from over.

Andrew Cockburn’s Letter From Washington investigates the nefarious regulatory influence of the megabank Citigroup, which, he writes, has been “involved in every speculative catastrophe of the past few decades.” In 1999, an earlier incarnation of Citigroup lobbied successfully for the repeal of the Glass–Steagall Act, and just last year the company overturned one of the most important provisions of the Dodd–Frank Act. It’s no wonder. As an outraged Elizabeth Warren (D., Mass.) pointed out in a speech on the Senate floor, seven current or recent high-level policy makers in the Obama Administration have close ties to Citigroup. What does this mean for the average American? To quote Dennis Kelleher, of the financial-reform group Better Markets, “taxpayers are now on the hook for high-risk derivatives trading.”

Also in this issue: Alexandra Starr on the predatory recruiting practices used to lure young African athletes to the United States; Scott Horton on The Senate Intelligence Committee Report on Torture; Christine Smallwood on Kazuo Ishiguro’s The Buried Giant; and an excerpt from Maggie Nelson’s new book, The Argonauts.