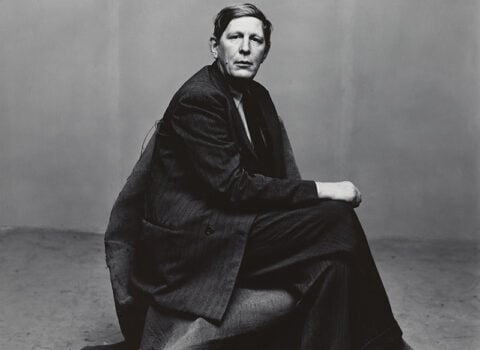

Motorcyles sit in the parking lot of Twin Peaks restaurant, in Waco, Texas, on May 17, 2015. Photograph by Erich Schlegel/Getty Images

Two summers ago my family and I moved from the anonymous suburbs of Chicago—Generica, a friend of mine calls such places—to Waco, Texas, where I had taken a job as a professor of humanities at Baylor University. As we drove in to the city, Siri gave us directions and noted that we had arrived in Wacko. “The jokes write themselves,” I told my wife.

As a native of Birmingham, Alabama, I already knew something about living in a place that has contemptuous narratives permanently affixed to it. Mention Waco, and the first thing that comes to most minds is the 1993 destruction of the Branch Davidian compound—or rather, the very existence of such a cultic compound, which for many Americans seems to be the really troubling thing about that event. Never mind that the violence was done to, not by, the religious weirdos; never mind that it wasn’t in Waco but ten miles east. Some fifteen miles north is West, Texas, where a fertilizer plant exploded two years ago, destroying a good chunk of the town and raining debris onto the cars flying up and down I-35. But the network news usually said “Near Waco, Texas . . .”

“It’s a nice place,” we said to our friends and family. Lots of live oaks. Good Tex-Mex food. Hole-in-the-wall taquerias and an emerging food-truck culture. A terrific coffee-shop-and-cocktail-bar (called Dichotomy, neatly enough). You can sit outside and drink your pour-over Ethiopian coffee in January sunshine then take long walks through the trees along the Brazos River. And rush hour lasts for fifteen minutes at the most. We like it here.

I was back in Chicagoland visiting friends when the news broke: dozens, maybe hundreds, of motorcycle gang members shooting at each other and the police in the parking lot of a restaurant called Twin Peaks. (Think Hooters, not David Lynch.) I had never been in the restaurant, but I had driven past it many times. It had been open less than a year, occupying a brand-new building in the Central Texas Marketplace, a shopping center at the junction of the interstate and a major state highway, featuring a Starbucks, a Panera Bread, and a Bed Bath & Beyond. The place was miles from my house, and there was really no possibility that my family could be in danger, but I texted them about it anyway. They hadn’t yet heard. We discussed the situation for a few minutes. There was certainly no need for them to alter any of their plans in the slightest: the shoot-out was over, arrests had been made, the wounded had been taken to hospitals. Our own daily habits never took us in that direction anyway. “Maybe y’all should stay home for the rest of the day,” I texted.

“Biker gang” is the usual shorthand, but they call themselves “motorcycle clubs.” The best known in Texas is the Bandidos, or, formally, Bandidos Motorcycle Club. There are about 2,400 Bandidos around the world, but Texas is where they’re famous, and dominant. They have a long history of extreme violence, but like their Californian counterparts, the Hells Angels—with whom they’ve had their share of clashes over the decades—they claim to have become somewhat domesticated, even bureaucratized, over time. They get regular counsel from lawyers who are themselves motorcycle enthusiasts. They belong to a national organization of like-minded groups called the Confederation of Clubs. According to one of those biking lawyers, William A. Smith, of Dallas, chapters of the Confederation meet fairly regularly to discuss “motorcycle safety and awareness” as well as to socialize. Many of them bring along their wives or girlfriends, who call themselves PBOLs: Proud Bandido Old Ladies.

Waco is a perfect location for regional chapters of the Texas Confederation of Clubs and Independents to meet: ninety minutes south of Dallas, two hours north of Austin, and three hours or so from both Houston and San Antonio. And Twin Peaks is just off the interstate, offering easy access for all concerned. Jay Patel, operating partner of the Waco franchise, seems to have seen in these meetings a windfall for his newly opened restaurant. He had already established a weekly Bike Night for local club members, but a chapter meeting is a much bigger deal: a couple of hundred bikers and companions can drink many gallons of beer and eat mountains of Buffalo wings. So when the Confederation approached him about holding a chapter meeting there, Patel agreed.

The potential trouble involved the Cossacks and their bottom rockers. The Cossacks, a comparatively small and new club, have for some years now been operating in Texas more or less by permission from the Bandidos, to whom they have paid a regular tribute (“dues”) for the privilege. But the Cossacks don’t want to pay tribute any more. They want to be independent operators in Texas, which is where the bottom rockers come in. Most bikers wear leather vests with the name of their club across the top and the name of the state in which they operate along the bottom. When the Cossacks started wearing bottom rockers reading “TEXAS,” the Bandidos grew very, very unhappy. But the Cossacks were committed: either the Bandidos would acknowledge their legitimacy and independence or there would be fights.

On May 1 the Texas Department of Public Safety issued a bulletin: “Tension between Bandidos OMG [Outlaw Motorcycle Gang] and Cossacks MC remains high in Texas.” “The conflict may stem,” the bulletin read, “from Cossacks members refusing to pay Bandidos dues for operating in Texas and for claiming Texas as their territory by wearing the Texas bottom rocker on their vests.” On the basis of this bulletin and other intelligence gained locally, Waco police approached Jay Patel to discourage him from allowing the Confederation chapter to meet in his restaurant. They claim that he was not receptive to their pleas.

1 At least one Cossack biker has disputed the claim that his club was not invited.

The chapter meeting was therefore held, as scheduled, on Sunday, May 17, around lunchtime. The Cossacks were not invited—they do not even belong to the Confederation of Clubs—but they came anyway, presumably as a declaration of independence.1 Some say the conflict started in the restaurant’s men’s room, some that it began in the parking lot when a bike ran over a foot. Waco police were already there, but the gangs, as they had promised, were undeterred from confronting each other. They went at each other with chains, bats, clubs, knives, and guns—though some of the gang members at the scene said that the police fired the first bullets. Soon nine were dead—all either Bandidos or Cossacks—with twice as many wounded and more than a hundred arrested. Word got around that more bikers were converging on the city to continue the fight, but nothing happened. By the time I returned to Waco the city was quiet, and the shoot-out had its own detailed Wikipedia page.

Waco Police Department spokesman Patrick Swanton was remarkably blunt in his criticism of the people who ran the restaurant. “The management wanted them here,” Sergeant Swanton said. “Management knew that there were issues, and we were here, but they continued to let those groups of people into their business.” Patel posted a statement to Facebook saying that he had had “positive communications” with local police, but Swanton called that statement “an absolute fabrication.” A day after the shoot-out Twin Peaks announced that “the Waco location will be closed and will not reopen.”

In all Sergeant Swanton’s communications with the public—and he was on TV and radio often in the days following the shootings—his frustration rumbled just beneath the surface, occasionally erupting into plain sight. Local and state law enforcement knew exactly what was coming, he said, but could do nothing to prevent it. They knew where and when the danger would be greatest; they knew that the bikers would be armed, even, perhaps, beyond the generous allowance of firearms that is made by Texas law; they knew that Central Texas Marketplace, at noon on Sunday, would be filled with families coming from church. But no crime had been committed, nor had an explicit threat to the public been made. There appeared to be no basis on which the police could act. They were dependent on voluntary cooperation from the management of Twin Peaks. When that cooperation was not forthcoming, the police had little choice, they say, but to show themselves in the danger zone on the appointed day.

Whether they could have found a less deadly way to intervene in the conflict is something that, as I write, cannot be known and may never be known. Did they fire the first shots? When they fired, did they have good cause to do so? It seems strange, in our time, to have a civic tragedy of this kind unfold with so little social-media evidence to sift through. We have quickly grown accustomed to images and reports tweeted and Instagrammed to the world then shared and debated—but almost all we have to document the Waco shoot-out is a series of photographs of gang members sitting in the Twin Peaks parking lot, casually overseen by police, checking their cell phones, a few feet from sheets of yellow plastic covering dead bodies.

Just a few weeks before the shootings and just a few miles from where it would happen, I sat in a seminar room and talked with my students about the political philosophy of Thomas Hobbes. Nearly four hundred years ago, in the midst of civil war in England, Hobbes argued that, if we are to avoid “the war of every man against every man,” it is necessary to create a political Leviathan: a single entity (perhaps a person, perhaps a group of persons) in whom all power is concentrated. Leviathan, Hobbes believed, is the only way we can be saved from our worst selves, saved from lives that are “solitary, poor, nasty, brutish, and short.” By the beginning of the twentieth century the great sociologist Max Weber claimed that that was just what had happened in the intervening centuries: we had granted a Gewaltmonopol des Staates—granted to the State a “monopoly on violence.”

But in America today all fifty states allow at least some people to carry concealed handguns; and forty-four states allow some form of “open carry” (for which some, but not all, require licenses). Especially in the South and West of the United States there are a good many people who think that even those laws do not go far enough in allowing citizens to compete, as it were, with the government in the possession of weapons of deadly force. (The political-theory wing of the Tea Party often contends that the founders meant for American citizens to be able to rebel, militarily if necessary, against their elected government, should that government grow tyrannical.) Many people will see what happened at Twin Peaks as illustrative of a Texas, or more broadly a red-state, “gun culture,” and while that’s not inaccurate, it makes more sense to see the gun use in this case as accidental: firearms merely provided the technology by which a body of beliefs were made manifest. By carrying guns, the Cossacks and Bandidos made concrete the claim that the state neither should nor does have a monopoly on violence.

But the outlaw gangs are, implicitly, making another claim as well: that the state’s sovereignty doesn’t extend to all of its citizens in all circumstances. When, in the months before the Waco shoot-out, tensions were building between the Bandidos and the Cossacks, some of the gang leaders sent a clear and simple message to police: Stay out of this; let us sort it out. This goes further than laying claim to the right to use force. The more deeply embedded a person is in biker culture, the more he exists in a kind of parallel dimension, an alternate moral universe with its own laws and mores. That universe is a territorial shame-and-honor culture, in which it seems obvious to the Bandidos that, thanks to their large membership and venerable history, they should be able to dictate what other bike gangs wear on their vests and should be able to exact tribute for the privilege of a “TEXAS” bottom rocker. That view came to seem less than obvious to the Cossacks, but not because they believed such a system to violate the freedom of Americans; rather, they understood that such a system of territory and tribute depends utterly on the strength of those who would attempt to enforce it. When the kings grow weak, or their rivals grow strong, the time has come to test the existing hierarchy of power. And that’s what the Cossacks did.

The problem, though, is that biker gangs don’t actually live in an alternate universe. They live in the same universe with the rest of us, who might want to get a nice lunch after church on a spring Sunday. They came fully armed to a new restaurant just off the interstate, and confronted each other a few feet from families eating enchiladas. The sound of gunfire jolted people who were buying towels. And if there were any nonbikers in Twin Peaks that Sunday, they must have been utterly terrified.

In the end, though, the bikers were the only ones who suffered injury and death. After the shoot-out and the arrests and the towing-away of bikes, Waco police, along with other law-enforcement agencies, investigated the wrecked restaurant. They discovered that many of bikers had discarded weapons they didn’t want the cops to find on them. Weapons were dropped in toilets and stuffed between sacks of flour. There were bats, clubs, brass knuckles. At the end of the third day after the shoot-out police had discovered, in the restaurant and in the bikers’ vehicles, 157 knives, 118 handguns, and one AK-47 automatic rifle.

Meanwhile, Texas legislators began, as scheduled, a debate about allowing “open carry”—yes, until June, when the legislation passed, Texas was one of only six states in which firearms could not be carried openly. Governor Greg Abbott said: “The shoot-out occurred when we don’t have open carry, so obviously the current laws didn’t stop anything like that,” which is certainly true. Indeed, the shoot-out at Waco had nothing to do with any existing laws, but rather arose from the dynamics of a subculture broken apart by rivalry and hostility but united in its belief that it should be allowed to function to a considerable extent outside the government’s laws.

When we hear about events like this shoot-out, we’re inevitably reminded of how unpredictable our lives are, how vulnerable we are to the contingency of being in the wrong place at the wrong time. But we ought also to be reminded that we live in a society in which the government has only some of the guns, and in which a great many people think that the government exerts far too much power over their lives. And as long as that is the case, those of us who prefer to remain unarmed risk getting caught in the crossfire—perhaps quite literally. Another law recently passed by Texas legislators requires state colleges and universities to allow concealed weapons to be carried on campus. Officials at Baylor University, my employer, have said that concealed carry will not be permitted on campus, which is a relief. Too many ironies intrude when I contemplate discussing the philosophy of Thomas Hobbes with people who are packing heat.

As I write, the consequences of the shoot-out are unfolding, in a chaotic parody of process that will continue for months, probably years. The Mexican restaurant next door has sued Twin Peaks; Sergeant Swanton has promised that video evidence will prove that the Waco police did everything right; bikers are suing to prove that the police did a great deal wrong; prosecutors are preparing their cases; families are grieving their dead.

When I got back to town and drove past the shopping center, I saw that police had set up barriers around the Twin Peaks parking lot, and for several weeks there were always police cars parked there, though perhaps just for show, with no one in them. A bank of stadium lights had been towed into the lot, and when the sun went down they were trained on the restaurant to deter vandals and the overly curious. All the restaurant’s signs were removed, leaving the bare building. When the rest of the shopping center grew dark and quiet, and the lights so brightly illuminated this one small space, Twin Peaks looked like a weird unattended shrine.