Our Sanitizer Saga

“Mrs. Gore admits that campaigning has its hazards saying PURELL was “just the thing for people who have to shake hands with lots of people and don’t have time to wash up between shakes.” Mrs. Gore revealed that the Vice President uses the instant hand sanitizer, as well as the President and Mrs. Clinton.… Said Paul Alper of GOJO Industries, the makers of PURELL ® …. using a hand sanitizer “can really get America on the right track.”

—“Republicans and Democrats Agree ‘Clean’ Is Good in Politics,” PR Newswire, August 30, 1996

“If you’re the perpetrator of a cough or of a sneeze or any kind of thing that makes you look sick, you get that look,” said a former Trump campaign official. “You get the scowl. You get the response of—he’ll put a hand up in a gesture of, you should be backing away from him.”

—“The Purell presidency: Trump aides learn the president’s real red line,” Politico, July 5, 2019

1. dreams and an argument

Photograph by the author

Among the disaster-tinged dreams I had from late winter into spring, the most persistent were those involving hand sanitizer. In one, I find a pump bottle of Purell at an Enterprise rental office, sitting in little wicker baskets which hold the employees’ personal effects, kind of like kindergarteners’ cubbies. I surreptitiously decant a few pumps into a container of my own. In another, I am approaching the cash registers at a large chain pharmacy, on my way to meet a former colleague at the beach, when I spot a display of 100-milliliter sanitizer bottles near the checkout. One is a conventional clear gel, and the other, by the same brand, is mentholated and opaque green, with the metallic glint of dandruff shampoo.

In my waking life, I was in a position to use soap and water nearly every time the need arose, which was especially fortunate because I have never liked hand sanitizer; I find that using it to “clean” your hands has the same insufficient feeling of drinking soda to quench thirst. Sanitizer has its place, of course, and there, too, I was covered. For reasons that should never be explained, I had ready to hand two gallons of pure ethanol and the equipment and supplies necessary to make my own sanitizer—not the runny stuff that emerged in March to fill the shortfall but a thick, luscious, crystalline gel. Clearly, though, it was too much on my mind and others’ minds.[1] As with masks, the fact of a shortage seemed to intensify the belief that what could keep us safe was just out of reach. But with sanitizer, unlike with masks, missteps and omissions in public health guidance—and errors in the very media reports that purported to fix misperceptions—were never really examined, and corrections were slow to emerge. These problems were not nearly as consequential as early fumbling over masks, but because sanitizer should have been a relatively simple thing to get right on the basis of well-established science, the ways the institutional responses went wrong provide a curious and cautionary case study. (The backstory of sanitizer is even bigger on curiosity points!)

2. Some recent history

Alcohol was likely used in some disinfectant capacity for hundreds of years before the pathogenic model of disease transmission became widely adopted. But such use wasn’t common in most people’s lives until Purell debuted as a retail product, in 1996. I have some scattered recollections of this sea change, but I remember more clearly how it had crept into certain areas of extra-clinical life within a decade, the particular locations and events: stadiums and concerts, buses and airplanes—places where restrooms were scarce, distant, or dirty. Some of these contexts were transitional or remote; most of them were very public.

Hand sanitizer for the masses was, or anyway was supposed to be, understood as a second choice or a low-effort top-up with respect to handwashing. By the time U.S. lockdowns began, though, sanitizer became an object of mania, endowed, beyond its actual usefulness, with an aura of protection; Purell was “the most sacred goo,” per a Washington Post headline.

One significant previous uptick had occurred in 2009, when the H1N1 pandemic contributed to a 70 percent increase in sales of wipes and gels over a period of about six months. But that bump was small in comparison with 2020. Between early February and mid-April, Instacart searches for “sanitizer” rose twentyfold (granted, Instacart itself was becoming more widely used by housebound consumers). Adobe Analytics reported a ninefold increase in online searches even earlier, from December to January—perhaps reflecting an initial wave of panic in the United States, before the temporary ascendancy of a presumption that the Chinese government had comprehensively contained the virus; Dr. Bronner’s, a legacy brand that added a sanitizer spray to its lineup in the early 2010s, told me that its own surge began in late January (in the form of overseas wholesale orders), spiked to about sixteen times baseline demand in mid-March, and settled in at a steady eight times projected demand for 2020.

3. cultural and chemical context

Sanitizer gel has a particular power of reassurance. It is engineered, transparent, purifying. It reeks of technology. Some of these associations come out of a specific cultural moment: the craze for clear products in the late Eighties and early Nineties. A lot of these were personal-care and cleaning products. One of the first was a clear Ivory liquid soap. I can pinpoint a Clean & Clear shampoo and conditioner set that I used in the winter of 1988–89, prior to which I had been a Prell child. There were deodorants and mouthwashes. In 1992, Pepsi introduced Crystal Pepsi, following a trail blazed by Clearly Canadian and other colorless non-caffeinated sodas, and in turn followed by Tab Clear. That same year, Zima debuted. By 1993, the year of Miller Clear beer and Crystal Clear gasoline, criticism and parody had crystallized. The New York Times and Los Angeles Times, among others, ran long pieces quoting experts who generally agreed that the trend had at least plateaued. That same year, Saturday Night Live made a memorable fake ad for Crystal Gravy, turning the virtue of transparency into a liability of visceral disgust. (The gravy was probably glucose syrup.)

SNL’s gag was effective because it uncomfortably conflated the two categories of purity messaging: ingestible products were more about virtue and naturalness, while the other products relied on a kind of “better living through chemistry” vibe. Purell didn’t appear until four years after Peak Clear, but it squarely took advantage of the second purity category’s enduring appeal. Its early TV ads were smartly produced and hold up well (transitions between, e.g., a microscope slide of bacteria and grocery-store plastic-wrapped chicken proceed with the flickering-lights cuts of a horror movie).

Alcohol-based sanitizers for clinical use had existed since the Sixties, and in 1988 Gojo Industries finalized development of Purell, which was made available to institutional purchasers in clinical care and the food-service industry[2] The civilian market really exploded after the early Aughts, and now thousands of variations on sanitizer gel can be found in the FDA’s product registry. Offhand, the least appealing one I noticed was cinnamon-bun scented. The most depressing one might be Joe Biden’s Build Back Better sanitizer, whose label rips off Dr. Bronner’s zany, text-dense design and features “Joe’s COVID-19 plan” ($8 for two ounces).

Hand-sanitizer gels like Purell are hydrogels, which are formed by the addition of certain polymers whose cross-linked chains can hold vast amounts of water with a high degree of dimensional stability. The polymer added to an aqueous solution to create a hydrogel is in functional terms a rheology modifier, which—with apologies to an entire branch of the physical sciences—indicates that it alters properties encompassing the way the gel flows (as a liquid) and holds its form (as a solid). Hand sanitizers use various polymers as rheology modifiers.[3] Some commonly used compounds include Carbomer (a trade name for C10-30 alkyl acrylate crosspolymer) and various derivatives of guar gum. These thickening agents and their hydrogel forms have plenty of other applications, from drug delivery to fracking to adult diapers. Aloe vera gel, to the great disappointment of many who were able to secure it in the dark days of DIY hand sanitizer, doesn’t really work as a rheology modifier.

4. “dangers,” unforced errors, and an information shortage

Depending on whom you asked in the industry, you got a slightly different answer about shortages: alcohol was expensive; the gellants that make the gel were hard to source; the orders for plastic bottles were backed up for months and months, a matter of there needing to be more machines made that can make the machines that make the bottles. With existing suppliers unable to meet the spikes, new products emerged to fill the gaps, but not before a significant stretch where DIY was the only option available to many Americans. This prompted a volley of hastily produced articles and video content by stir-crazy staff writers feeding the cruel, insatiable hunger of their organizations’ web metrics. The messages of these articles came in two prongs: “Making your own sanitizer is easy!” and “Making your own sanitizer can be ineffective, even dangerous.”

Most of the references I found regarding the danger of DIY were either vague or concerned a single incident, in which the owner of a few New Jersey 7-Elevens, who was later arrested, is said to have cut some form of commercial sanitizer with water and sold it in refillable spray bottles. The solution gave “burns” to several children who sprayed themselves (the diluted sanitizer was apparently a foaming type, and probably one whose microbicidal agent was not alcohol but a quaternary ammonium compound, such as is commonly found in surface wipes, and which was not at the time recommended for SARS-CoV-2). A far more widespread sanitizer risk among children is intoxication by ingestion. And recent discoveries of poisonous sanitizer (i.e., more acutely toxic if ingested) seem limited to stuff that was industrially produced.

The matter was more complicated, and interesting, when inefficacy itself was the potential danger. Dodgy recipes circulating on social media listed standard 80-proof liquor as an ingredient, which means that before any other component is added there is only 40 percent alcohol by volume—just two thirds the recommended minimum. And even when warnings against such formulations broke through the noise, there were many expressions of frustration about how a humble homemade something was better than high-handed advice to use nothing.[4] This reasoning might be true of other less-than-ideal situations: basic face coverings worn by two people, one contagious and the other uninfected, will still provide a benefit of reduced transmission. But the false sense of security that one might get from using a sanitizer with significantly reduced concentration and efficacy (say, vodka and aloe) was a different kind of problem—it would arguably be better to use nothing and behave accordingly.

The correctives that the media offered contained further errors. These mistakes, miscues, and elisions, sometimes attributed to distinguished doctors or presented by lab-coated speakers with advanced degrees, were very plausibly responsible for at least some of the mistaken assumptions and false conclusions floating around. A content-mill approach by media outlets created or furthered the popular idea that hand sanitizer needed a special recipe. These recipes often called for ingredients that put the formulations out of reach of many Americans on the back end of a buying panic, and potentially rendered useless plain rubbing alcohol that would have been a far more effective solution. These sources got a lot of basic math and science wrong, and called for vast quantities of moisturizing agents (such as aloe vera gel or glycerin) in proportions that had no basis in any kind of established research and made it impossible to produce effective sanitizer without extremely concentrated alcohol. (For a full discussion breaking down what one representative cluster of advice pieces got wrong and how they fed off one another, see Appendix 2. For a detailed discussion of home formulation, see Appendix 1.)

Complementing the lack of clear and sound information about making sanitizer (it would be implausible to expect the federal government to join the media as an enthusiastic arbiter of home sanitizer hacks, but they might perhaps have offered specific prohibitions as a lesser evil), there was no centralized, authoritative guidance about using sanitizer. In this area, the CDC and the media failed to provide simple, consistent, rational messaging; there was the endless repetition that handwashing was superior to sanitizer, and good information on how to handwash, but little about how to make sure sanitizer was deployed effectively.[5] One CBS article with a recipe for sanitizer (also discussed in Appendix 2) contained the following: “While soap and water is also effective against the virus, hand sanitizer is often more convenient. ‘We are a lazy society—no one wants to sit around for 20 seconds and wash their hands,’ Dr. Agus said.” David Agus is the best-selling author and oncologist who treated Johnny Ramone’s prostate cancer; he seems to be quoted here because he is a CBS commentator and they needed a quick take, not because he is a subject-matter specialist. Responsible sanitizer application, in the available research, requires precisely what Agus frames as not necessary: twenty to thirty seconds of standing around. (In hospitals, the time savings from sanitizer comes from not having to travel back and forth to wash stations.) But finding advice as simple as “use sanitizer in the same manner and for the same amount of time you would use soap” proved elusive. There was also the rarely discussed question of how much to use: 2.5 to 3 milliliters or so (a generous half teaspoon). That quantity is a little awkward to handle as a poured liquid and a little slow to dose out with a spray.[6] But a gel!

5. the sanitizer boom

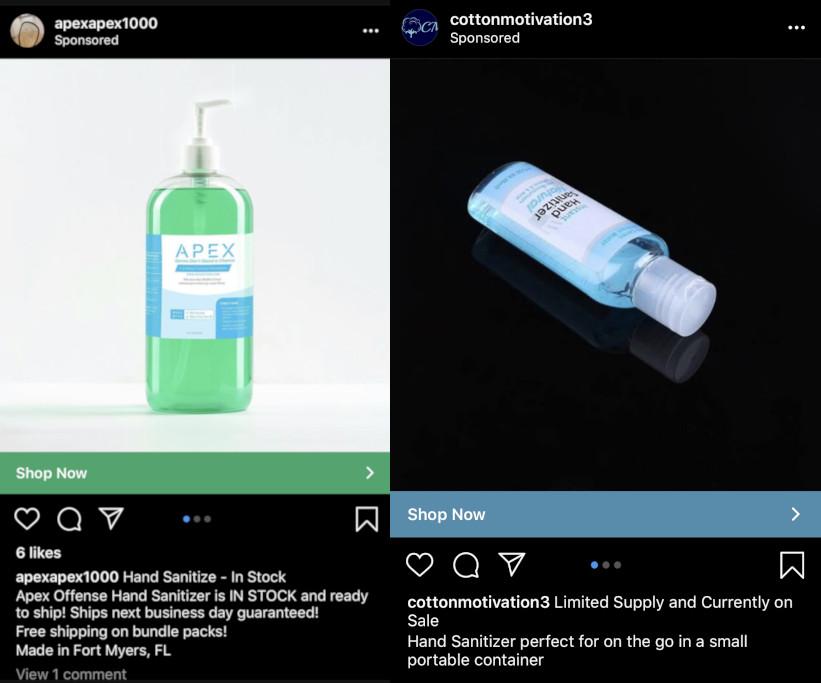

By the time commercially produced gel sanitizer was once again widely available, around the beginning of May, an array of new products had proliferated. Many of the roughly 200 Instagram ads for sanitizer I was served between mid-February and the end of April depicted offerings that did not exist a few months earlier. (Facebook’s ad engine eventually backed off on sanitizer and concluded, as far as I can infer, that I was producing THC vape liquid at scale.)

The majority of these sanitizers were liquids rather than gels, and the ingredients and marketing were impressively diverse. There were gently gendered fancy-hippie options for coastal elites, while certain gruff denizens of Real America might opt for the appealingly named Hand Shit or combat-themed gels that would look right at home on the webbing of a tactical vest. One brand, of a yoga-ish flavor, quoted the Instagram poet Rupi Kaur; others enticed the consumer with judiciously chosen typography—turn-of-the-century pharmacy, monochrome Helvetica (black on white), monochrome Helvetica (white on black), graffiti script in fluorescent blue with a circa-1991 salon-product vibe. The packaging ranged from the standard cheap plastic pump bottle (lately something of a premium commodity) to aluminum or brown Boston glass bottles to round-edged rectangular spray canisters reminiscent of an iPhone 3, while prices ranged from $33 an ounce to $45 a gallon (from a rug store in Los Angeles). Some were even non-alcohol-based, touting the benefits of probiotics or colloidal silver.

I contacted some of these brands to spot-check how manufacturing was taking place and what the constraints on it were. It became clear that a fair amount of what was being done stretched the rules or happened off the books. The first constraint was the regulatory environment. The FDA advisory extending permission to non-registered facilities to produce sanitizer mandated that they produce according to the World Health Organization protocol, narrowly conceived. Some new liquid sanitizers have additives, or depart from the acceptable percentages, and so should be registered with the FDA as over-the-counter drugs but haven’t been. The FDA advisory also requires that the alcohol be denatured (made unpalatable, with ingredients that range from just gross to mildly poisonous). The denaturing isn’t noted on the FDA’s one-size-fits-all sample label, and some sanitizer makers ignore the requirement, probably for fine reasons: One distillery, in New York City, told me that they didn’t want poisons sitting around in a facility that still actively produces liquor, while another distiller, Maine’s Split Rock, have stuck with the advisory to the letter. And although foams, aerosols, and gels are not allowed to be sold unless FDA registered, I found some underground gel makers who seemed legit. On the other hand, a friend’s father who ordered sanitizer gel from China, which boasted of mysterious “amino acids,” wound up with a pump bottle of gellified water. Then there were sundry false claims scattered about, concerning a given product or its competitors.

I asked the COO of Dr. Bronner’s, which uses an FDA-registered third party to produce its sanitizer spray, whether the company had considered moving into gel, since the market was ripe for it, or whether, in a rare turn, its technological sheen was at odds with a brand identified with earthiness. “That’s poetically true,” he said after consideration, “even if it’s not prosaically true.”

As we reach the height of fall, the gels are back in full splendor. At several drug stores I have visited, they appear in perpetually stocked displays of artless desperation, a jumble of sizes and brands stacked directly on the floor near the entrance. I have wondered if the appeal of tranquil self-care will sustain the $20 patchouli-infused sprays and the all-in-it-together-ness will sustain the distillery purchases. A related question is how all this might affect Purell’s absolute market share. After selling the brand in the mid-2000s, Gojo Industries bought it back in 2010—to (one assumes) triumphant vindication. The product has long enjoyed not only the primacy of its quarter-century track record but a singular authority. The packaging has remained consistent, with just enough “design” to be distinctive, tempered by the restrained look of a medically adjacent product. The gel’s fragrance is immediately recognizable. Its translucent, slightly tinted aloe version looks so much more soothing than, say, the weird Nickelodeon-slime green of Germ-X Aloe.

6. coda

A friend was in a bathroom, in a building in a part of Brooklyn, near Prospect Park, that even before regentrification was a bit grand. She was there visiting her friend’s house for Shabbat dinner. In the bathroom, she opened a cupboard to find dozens of pristine bottles of Purell. These people are insane, she thought to herself. She later found out that the friend who had invited her to dinner had married into the family that owns Gojo Industries.

Appendix 1:

gel recipes and further fun facts

Video Player

What brought you here, reader, so far into this dyspeptic and discursive website article I wrote before the summer and then set aside until after we headed back to school (sort of)? Schadenfreude over another unforced media error? Nineties consumer nostalgia? Distraction on the eve of a fraught election? Dr. Zuckerberg’s Stupendous Fully Automated Algorithmorator? It probably wasn’t, at this point, questions about how to make sanitizer gel. But who knows! Maybe my weighing the merits of different formulations will prove useful for the ages. Maybe you are curious about thickening up your watery face wash, or have correctly identified making your own cosmetics as a delightful way to waste time. Maybe you panic-bought a bunch of liquid sanitizer for your Masonic lodge, large family, or rug club and now wish to gellify it.

While certain industrial applications of hydrogels are complicated and require tightly controlled processes, making sanitizer gel is pretty simple. The suggestions I present are the result of tinkering that I undertook in March and April. The basic shape of it is that you need to combine various liquid ingredients (such as alcohol, water, hydrogen peroxide, glycerin, aloe vera gel, etc.) with various solid ingredients (such as rheology modifier, aloe vera powder, pH adjuster, etc.). But typically not all of those.

a) alcohol

First, one chooses which alcohol to use. Yet another misleading claim floating around in the DIY coverage held that ethanol is more effective against viruses. This is true, but the “more effective” part is about the fact that ethanol is better than isopropanol at inactivating non-enveloped viruses (such as adenoviruses and rhinoviruses), while both are effective at inactivating enveloped viruses (such as coronaviruses and herpesviruses). An in vitro test of both WHO formulations (described in Appendix 2) at varying concentrations actually found isopropanol to be more effective than ethanol at inactivating coronaviruses at lower concentrations.[7] Isopropanol is a bit more drying than ethanol, but alcohol-based hand sanitizers, overall, may actually prove less drying than handwashing, so this probably shouldn’t be a major consideration. Ethanol evaporates more quickly, but if you dispense a proper amount, and especially if you’re dealing with gel, this likewise shouldn’t affect your decision. Ethanol is usually more expensive, because of excise tax, but prices are weird these days. I tried using both, but for most of the formulations I used ethanol, just because it smells better. Starting from 100 percent ethanol also meant the math was never going to require much thought when scaling proportions. Because the effectiveness doesn’t decrease as you rise in the 60 to 90 percent range, there’s no harm in keeping percentages a bit high—between, say, 70 and 80 percent alcohol by volume. Pure ethanol is also by definition not denatured by methanol, which can mess up the math, because a “95 percent” ethanol that is actually 10 percent methanol and 5 percent water is effectively 85 percent useful alcohol, since methanol is not an efficacious microbicide in the way isopropanol and ethanol are. Ethanol denatured with isopropanol is fine, and less toxicologically risky than methanol. But it seems likely that anyone reading these recommendations who wishes to follow them will simply use what they already have lying around.

b) measurement

One thing that makes model formulas a little annoying is that the ingredients are typically by weight; solids are easy to weigh, whereas for most people it’s more convenient to measure liquids at room temperature by volume. Again, I assume that most people now have access to the hand sanitizer of their choice, but if you’re going to do this, it probably makes sense to cross-convert so you can use volumetric measurement for liquids and scales for solids. In that case, you need a scale accurate to 0.01 gram and a modest capacity, and graduated cylinders (10 milliliters and 100 milliliters should be sufficient). If you want to go by weight, you need only a scale, but probably with a minimum capacity of 500 grams, because a lot of that gets used up by the tare weight of containers. Level kitchen teaspoons are 5 milliliters, tablespoons 15 milliliters, and if you have half and quarter teaspoons in a set, those can be handy as well, as a substitute for a smaller graduated cylinder.

c) mixing (and matching) ingredients

I tried a range of formulations, starting with the WHO protocol for ethanol (modified to 84 percent ethanol) and adding one of several rheology modifiers. Then a 70 percent ethanol solution with concentrated aloe vera powder instead of glycerin (I used 100x concentrated powder, about 0.2 gram per 100 milliliters of solution), which is dissolved in the water before it’s added to the rest. Then I tried replacing the plain water partially or entirely with various hydrosols (basil, witch hazel, etc.), because my mind wanders and I am undisciplined and friends I took orders from started making weird requests. For another version, I used aloe vera gel, which serves as both the water and the moisturizer. In yet other versions, I used propanediol instead of glycerin, with or without aloe, as it’s a less tacky moisturizer.

How hung up do you need to be on moisturizers? Probably not that hung up, unless you’re using sanitizer constantly, and even with heavy use (at least in a clinical setting), commercial hand sanitizer may be less drying than handwashing. At minimum, it’s not obviously more drying. With any other thing you think about adding, you want to check that it doesn’t have some secret microbe-enhancing property and that it doesn’t drastically change the pH. (None of the simpler preparations should do either of those things, so you don’t need to worry about pH targets and testing.) Some compounds have unexpected benefits beyond the primary association. Purell contains, for example, tocopheryl acetate, a.k.a. vitamin E, which moisturizes and also provides mild microbicidal activity that makes it useful as a preservative.

To mix, I used either a magnetic stirrer or a low-shear setup on an overhead mixer. A magnetic stirrer uses a magnetic bar that you place in the bottom of your container; the stirrer’s base contains an internal magnetic rotor that turns the bar. This allows you a lot of flexibility in terms of containers. You can even use a closed container, which helps prevent evaporation. Stirrer bars can tolerate some eccentricity and convexity in the bottom of a container. But with a gel, you can’t plan to mix more than 250 milliliters, depending on the shape of the container and the thickness of the gel, because the stirrer doesn’t have sufficient muscle to move viscous liquids, especially compared with an overhead stirrer (a steel egg-beater attachment, a paint mixer on a drill, or, in my case, a large Forstner bit on a small milling machine). Some people use the sort of handheld, battery-operated mixer designed for frothing milk.

d) order of operations

Measure your liquid ingredients. Dissolve solids other than the rheology modifier in water. Add the water to the alcohol. If using glycerin, reserve some of your measured water (either distilled or boiled and cooled) to help flush residual glycerin from its measuring vessel. You can combine your finished liquid and your rheology modifier in stages or sift all the powder into all the liquid fairly quickly.

If you don’t have some kind of power stirrer, you can sprinkle the rheology modifier atop the solution, close the container, leave it overnight, and then manually stir it a few times. The swelling of the gellant does a lot of the mixing for you.

If you’re using a magnetic stirrer, you can keep it running for as long as you like to get things thoroughly blended, but remember that with either magnetic or overhead, you want a low-shear mixing process: an initial vortex is fine, but no splattering or serious displacement. The thickening liquid will soon make the vortex disappear and limit the maximum speed of a stirrer bar. With the overhead mixer, on which I could dial in the speed, I started at 500 rpm and increased to 1,500. If you’re using an open-top vessel, about 90 minutes of mixing should get enough of the gelling agent mixed in without posing any significant evaporation risk.

You will need a clean spatula or other appropriately sized scraper to get the finished gel out of the mixing container and into the dispenser (if they are not one and the same).

e) choice and quantity of rheology modifier

Some of the rheology modifiers I tried were guar-derived, but plain guar gum is difficult to use at home. It is preferable to use synthetic compounds that can be added in a single shot to the hydroalcoholic mixture to produce gel, can tolerate high concentrations of alcohol, and aren’t finicky to work with in terms of pH (changing it or being changed by it). The company Seppic makes several products, including Sepimax Zen; Solvay makes Jaguar HP-120; and Jingkun Chemical makes Guarsafe JK-303 (last year, Jingkun produced 100 metric tons of the compound, and this year, a company rep told me, it’s producing that amount about every ten days).

The rheology modifier I used most of the time was polyacrylate crosspolymer-6 (available in consumer-size quantities as Gelmaker PH or Sepimax Zen), for which the manufacturer recommendation starts pretty low. (Unbranded hydroxypropyl guar, Sepimov, and Carbomer are among other options readily available in small quantities to the consumer; always check whether a given product will require a pH adjuster to add to the mix or a specific order of mixing.) Polyacrylate crosspolymer-6 was satisfactory at 0.8 gram per 100 milliliters in solutions ranging from 70 to 84 percent ethanol—a little on the thin side, but not as thin as some of the gels currently on the market. I went as high as 2.5 grams per 100 milliliters of hydroalcoholic solution to get a significantly thicker gel. It seemed like isopropanol required a bit more gellifier than did ethanol, but I didn’t experiment with it enough to pin this down, and it could have been my imagination.

Keep in mind that you might be better off going with a little more thickener at the outset. It’s a hassle to add more powder to a gel later on.

f) just give me a simple recipe

Add 100 to 300 percent the manufacturer-recommended minimum amount of rheology modifier (for hydroalcoholic gel) to previously mixed WHO-formula liquid, or rubbing alcohol plus glycerin, and call it a day. The percentage will work out fine.

Rough WHO-derived liquid formulas, approximately 1,000-milliliter yield, are as follows.

Using 70 percent isopropanol:

To one 946-milliliter or 1,000-milliliter bottle (halve quantities above if your bottle is 473 milliliters), add 10 milliliters glycerin and 40 milliliters H2O2 (3 percent). Do not add water. Add rheology modifier (e.g., 15 grams polyacrylate crosspolymer-6).

Using 96, 98, or 100 percent ethanol, or 91 percent isopropanol:

To 800 milliliters of one of the above, add

10 milliliters glycerin, 40 milliliters H2O2 (3 percent), and 150 milliliters distilled or boiled water (cold). Add rheology modifier (e.g., 15 grams polyacrylate crosspolymer-6).

g) bottling

You could use an empty sanitizer container with a flip top or a pump. But if you’re passing these out to people or making a bunch of different small batches as a way to pass time, I found that low-density polyethylene vape-fluid bottles are good. They have safety caps and handy removable nozzles, they don’t leak, they’re cheap, they are in stock everywhere, and they come in many sizes. The bottle mouths are a little small for easy filling, but eh.

h) so, how is it?

It’s nice. Silky smooth. I find it more appealing than commercial versions. One of my neighbors said she likes it better than her store-bought one. Maybe she was just being kind.

i) In a pinch, to remember for some future supply-chain collapse

Plain rubbing alcohol is hand sanitizer.

Appendix 2:

tracking bad information

One example of how muddled the media advice was may be found in this cluster of cross-referenced informational pieces.

The first component is a popular LiveScience video on YouTube, which during the sanitizer drought racked up over a million views. It recommends a two-to-one ratio of 91 percent isopropyl alcohol and glycerin, which ensures a final mixture of at least 60 percent alcohol by volume. The stated basis for this, according to a companion article on LiveScience.com, is the CDC’s recommendation of a two-to-one alcohol-to-emollient ratio.[8] It does not appear to be the case that the CDC ever actually offered this advice. And in context, it doesn’t make any sense: the video mentions aloe vera gel and glycerin interchangeably. But aloe gel is mostly water, while glycerin is typically available with 0 to 2 percent water. A formula with one third glycerin would contain an order of magnitude beyond what is necessary and would just make a sticky mess. (And although high concentrations of glycerin inhibit bacterial growth—that’s why it is sometimes used to preserve human tissue samples—there is evidence that at lower levels, using more than necessary can actually reduce the effectiveness of alcohol-based hand rubs.) The video then goes on to offer, as an alternative formula if higher alcohol content is desired, a three-to-one formula, and the departure from the original, dubiously sourced ratio is not explained or explored.

The LiveScience.com article, and a CBS article on which it heavily draws, present further problems. Both mention in passing a range of 60 to 95 percent alcohol content. (The FDA range is actually 60 to 95 for ethanol and 70 to 91.3 isopropanol, but the agency’s use of “alcohol” to mean ethanol has confused many; at any rate, 60 percent isopropanol, if COVID is your concern, likely isn’t a problem [See Appendix 1’s item (a)].) In spite of the warnings about a lower limit, neither of these sources explain the upper limit, even though consumers could at the time get their hands on ethanol and isopropanol more concentrated than the rubbing alcohol (which can be either type of alcohol) available in pharmacies. In February and March, the highly concentrated stuff (especially in large quantities) was, owing to the mysteries of supply chains, sometimes easier to source than the drug-store kind. Above 95 percent concentration, ethanol will rapidly coagulate the outer layer of an enveloped virus like SARS-CoV-2, harming it but potentially not penetrating to inactivate it completely.[9]

The CBS article then wanders into some garbled sentences that appear to endorse the use of these highly concentrated alcohols, while what they actually mean—positing the two-to-one ratio as ironclad—is also wrong. Many who took this ratio as gospel complained that it rendered the overwhelmingly common form of 70 percent rubbing alcohol—already present under sinks and in cupboards in tens of millions of American homes—supposedly unusable (because two-to-one starting with 70 percent produces 46 percent). Another option—as is the case here—was sometimes mentioned in passing with a kind of fearful reverence. This was the WHO hand-rub formulation, contained in a how-to “Guide to Local Production” for clinic-level operators in the developing world who need to make their own hand sanitizer cheaply. (Hand sanitizer is, of course, also used in lieu of handwashing by plenty of medical shift workers in advanced industrialized countries.)

The WHO pamphlet lays out two formulas resulting in either 80 percent ethanol or 75 percent isopropanol solutions. These formulations are, indeed, exactly what relaxed FDA guidelines have permitted shortfall-filling commercial facilities (distilleries and the like) to produce without fear of being pursued by regulators. Both WHO formulations call for 1.45 percent glycerin as well as 0.125 percent hydrogen peroxide (to kill any hardy bacterial spores present in the containers). There is some flexibility: whatever is readily available, miscible in hydroalcoholic solution, stable over time, and allergenically low-risk may be substituted as an alternative moisturizer for glycerin, and the amount of glycerin can be lowered if the skin feel is too tacky.[10] You adjust the amount of alcohol depending on how concentrated the alcohol you have on hand is, and the balance of the formulation is water; CBS’s mention of the WHO protocol not only omits the water, it reproduces verbatim the (other) quantities in the WHO pamphlet, which are for making ten liters at a time. It seems the length of the pamphlet, the equipment depicted in the photos, and the scale of production intimidated CBS and other outlets, which assumed that things like large mixing bowls (not necessary), large quantities of supplies (not necessary), and an alcohol hydrometer (not necessary, but available online for under $10) put this beyond the reach of the casual user.

What seemed to have gone missing from so much often discouraging (in intent or in effect) advice was that the easiest, most obvious, most accessible home formula would have involved slightly adapting the WHO protocol to use 70 (or 91) percent drug-store alcohol. That and scaling down the ten-liter quantities by a factor of ten (a standard quart bottle of isopropanol is 946 milliliters). Or twenty, or forty. You can add a little glycerin and some standard 3 percent hydrogen peroxide to your bottle of rubbing alcohol. And that’s it. Even starting with 70 percent, plus the other ingredients, and forgoing water (already there as the other 30 percent), you still wind up over the 60 percent threshold for safe, broad-spectrum antimicrobial activity.

The media, pervasively, failed to hit on this simple fix—perhaps, in some instances, because it wasn’t sufficiently engaging as advice. (The CDC, as noted above in this article, somewhat understandably approached home-sanitizer advice with broad discouragement.) Many people who could have rested easier were instead told that a magic formula required them to dilute the acceptably potent alcohol they already had, meaning that their choice was between unacceptably weak sanitizer and nothing at all. And they probably would have been fine with just a plain bottle of rubbing alcohol. It doesn’t evaporate that fast, and whatever it lacks in added moisturizers can be compensated for with the scientific marvel of lotion.[11]

[1] See, e.g., Schredl and Bulkeley, “Dreaming and the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Survey in a U.S. Sample.”

[2] In a search of a few databases, the earliest mention I turned up was a weird 1989 article from the Hartford Courant which boasts that servers at the local food festival will be cleaning their hands with “PUREL.” Although Gojo officially dates the consumer launch to January 1997, that version of the product was announced, advertised, and available in 1996.

[3] Polymer does not mean “plastic” in the industrial sense but a category of molecule that links together multiple similar smaller molecules—monomers. Polypropylene and nylon are examples of synthetic polymers, while, for example, DNA—a polymer consisting of nucleotides—occurs in nature.

[4] The comments on one New York Times article offer a characteristic snapshot of sentiment, with posters ranging from huffy sanitizer-deprived hoi polloi to a mad dermatologist who recommends combining Everclear and Cetaphil.

[5] There were a few exceptions, including some YouTube videos that did a good job amid the widespread stupid ones. But after reviewing plenty of reporting that consisted of the same basic points being recirculated and weirdly selective quoting of experts, I would say that nothing consistently intelligent or incisive made it to the top of the pile.

[6] Later on, a World Health Organization poster spelling out both technique and quantity for hand-rub use began to circulate widely.

[7] So perhaps even the sub-60-percent formulations of rubbing alcohol would have been pretty effective. (But you didn’t read that here!) The basic guideline of 60 percent, which is based on ethanol, is a good safety margin; the threshold above which broad antimicrobial activity is pretty consistent within thirty seconds is about 54 percent alcohol by volume. Isopropanol has historically been exceedingly rare as an ingredient in U.S.-distributed hand sanitizers; an FDA survey looking at a 52-week period in 2008–9 put its market share at 0 percent of products sold.

[8] Moisturizers work in several ways. If you read around in cosmetics literature, you might find these properties trifurcated into occlusive (forming barriers against evaporation), humectant (tending to draw in water from the air), and emollient (softening the skin). A single compound can be more than one, so I have just used “moisturizers.”

[9] In other news sources, there was a pervasive suggestion that water is necessary to keep the alcohol from evaporating too quickly on the hands, which is not actually the concern. Also, just as a general note, it’s important to keep in mind that the majority of research on sanitizers is oriented toward bacteria, not viruses, as befits a clinical context.

[10] If 1.45 percent can feel too sticky, imagine 33.33 percent. The recent study alluded to above that found that 1.5 percent glycerin actually reduced the efficacy of the formulation, and recommended 0.5 percent instead, might mean the WHO formula itself is due for reevaluation.

[11] The FDA’s idiotproofing note that “the agency lacks verifiable information on the methods being used to prepare hand sanitizer at home and whether they are safe for use on human skin” would appear to be untrue of rubbing alcohol, which is designed to be applied to the skin.