Discussed in this essay:

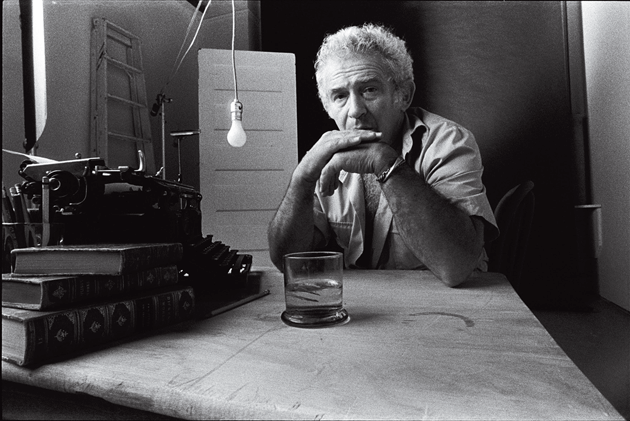

Norman Mailer: A Double Life, by J. Michael Lennon. Simon & Schuster. 960 pages. $40.

Mind of an Outlaw: Selected Essays, by Norman Mailer. Random House. 656 pages. $40.

Of course, the Young Writer had known of Mailer all his life. How could he not have known? He’d been raised in New York City, where Mailer twice ran for mayor — the first campaign brought to a premature end by Mailer’s drunken stabbing of his second wife, the next suffering a more conventional death, of voter indifference. All this before the Young Writer’s time, but the legend had persisted.

So the Young Writer had known of Mailer, but what had he known, exactly? The man’s last great work, The Executioner’s Song, had appeared in the year of the YW’s birth, after which Mailer had shown poor form by continuing to live and write for almost three decades. He became less a writer than a pundit, with an opinion on every subject that strayed into his view. The opinions themselves — on Bill and Monica, on 9/11, on the Bushes and their Gulf Wars — were predictable and unimaginative or worse: the YW remembered, for example, Mailer’s contention that the New York Times book critic Michiko Kakutani was a “kamikaze” who’d kept her job by means of racial and gender tokenism. This wasn’t provocative in an interesting way, just ugly and stupid. (That Kakutani was an analphabetic disaster whose continued employment by the paper of record was a genuine mystery only made matters worse: to put things in Mailer’s terms, his opponent was showing her chin, and he had opted to punch below the belt.)

In search of models for literary conduct, the YW looked instead to Pynchon, Gaddis, and DeLillo — writers with every bit of Mailer’s ambition who seemed by their actions to say that little could be won from too much contact with a fallen world. They could not be found on television, extemporizing about plastic or drugs or masturbation. They just wrote novels. Occasionally Mailer still did, too, but they were retellings of the Gospels or of Hitler’s childhood — a television host’s idea of important novelistic subjects.

Yet for all that, Mailer continued to loom, and he seemed to demand a reckoning. How could the Young Writer not engage in some way the man so many regarded as the very image of the serious American novelist? But then, in 2007, Mailer died, and much of his celebrity went with him. Perhaps no reckoning would be required after all. Everything seemed settled until this fall, when two volumes appeared — J. Michael Lennon’s Norman Mailer: A Double Life, and The Mind of an Outlaw, a career-spanning collection of Mailer’s essays. The books had a heft and range that insisted, as Mailer had insisted throughout his life, on his importance. The question naturally presented itself: Did Mailer matter?

The man himself would have understood the question well. He’d spent a lot of time talking about the novel that would alter the consciousness of his age. Most writers begin with such ambitions — the Young Writer certainly had — but Mailer was encouraged both by disposition and by early success to persist in thinking he might actually have a culture-changing book in him.

As Lennon reports in his biography, the twenty-year-old Mailer sought to defer his entry into the Army on the grounds that he was finishing “an important literary work” whose analysis of the fascist and democratic minds might have “some relevance to the war effort.” At the time, he was a recent Harvard graduate who’d won a national short-story prize and written hundreds of thousands of unpublished words but done nothing to suggest his work in progress would have world-historical significance. When the deferral was denied he gave that work up, but he was already telling his first wife of his plans for “THE war novel” before he arrived at Fort Bragg for basic training. It would be the only one of Mailer’s many grand projects that was completed more or less as conceived. More than 700 pages long, the book was finished in fifteen months and published in 1948, when Mailer was twenty-five. In an introduction to the fiftieth-anniversary edition, Mailer would describe The Naked and the Dead as “a best-seller that was the work of an amateur”:

The book was sloppily written in many parts (the words came too quickly and too easily) and there was hardly a noun in any sentence that was not holding hands with the nearest and most commonly available adjective — scalding coffee and tremulous fear are the sorts of thing you will find throughout.

Mailer had his reasons — so the Young Writer came to believe — for insisting on the novel’s weaknesses, but he happened also to be right. From its first lines the book has the pitch of a middlebrow bestseller:

Nobody could sleep. When the morning came, assault craft would be lowered and a first wave of troops would ride through the surf and charge ashore on the beach at Anopopei. All over the ship, all through the convoy, there was a knowledge that in a few hours some of them were going to be dead.

A cast of characters is introduced, a platoon getting ready to go on patrol in the Pacific, each soldier sketched in ready-made language: “He was a big man about thirty years old with a fine mane of golden-brown hair, and a healthy ruddy face whose large features were formed cleanly.” If anything about the book truly challenged its time, it was the depiction of the soldiers’ language, although even this was bowdlerized at the publisher’s request. (The word “fug” and its variants appear more than a hundred times, which reportedly led the actress Tallulah Bankhead, on meeting Mailer for the first time, to say, “So you’re the young man who doesn’t know how to spell ‘fuck.’ ”)

For all that, the YW found the book gripping and sometimes quite funny, an impressive achievement for a writer in his early twenties. At the time, several critics had seen in it THE war novel Mailer had hoped it would be. And it was a hit, spending nineteen weeks at the top of the New York Times bestseller list and staying on the list for more than a year. It made its author rich and famous, both of which — despite steadily increasing alimony and child-support payments — he would remain for the rest of his long life.

So great was Mailer’s fame that it survived when he followed his long, panoramic, conventional-but-inviting bestseller with a book that was none of these things. “Probably I was in the war,” begins Barbary Shore, the story of Mike Lovett, an amnesiac who takes a room at a boardinghouse in Brooklyn. He wants to write a novel but has no memories to draw on. He believes this loss occurred in combat, but when he tries to recall the experience, stock war images appear instead:

I could almost picture the crash of an airplane and the flames entering my cockpit. No sooner had I succeeded, however, than the airplane became a tank and I was trapped within, only to create another environment; the house was burning and a timber pinned my back. Such violence ends with the banality of beads; grenades, shell, bombardment — I can elaborate a hundred such scenes, and none seem correct.

The whole conceit rebuked the realism of The Naked and the Dead, and it angered Mailer’s fans. The book also displayed the author’s growing interest in Marxism, an unusual hobby for a mainstream American writer in 1951; Lovett’s education in the topic by a former Communist Party member takes up many pages. Time called it “paceless, tasteless and graceless.” For his part, the YW found Barbary Shore to be a mess, but a mess born of the admirable impulse to reflect the weirdness of the postwar period as Mailer himself experienced it. The awkwardness of the book was the awkwardness of a major talent sorting itself out.

Mailer’s next novel also concerned a would-be novelist and war veteran, this one named Sergius O’Shaugnessy. Set in Desert D’Or, a southern California town modeled after Palm Springs (which Mailer had visited for all of twenty minutes on his way to Hollywood), The Deer Park was dropped by his publisher on grounds of obscenity and eventually declined by half a dozen other major houses — an astonishing turn given that its author had published the best-selling novel of the year less than a decade before. When it was finally picked up, in 1955, The Deer Park sold better than Barbary Shore — even spending a few weeks on the bestseller lists — but the reviews were nearly as bad. The YW supposed that the book would have received more kindness, if less attention, had someone other than Mailer written it. Perhaps it would even have survived as a minor classic, a scathing satire of blacklist-era Hollywood, written during the era itself. At times the book has an odd, aphoristic brilliance, and it includes a line that became central to the Mailer legend, about a “law of life so cruel and so just . . . that one must grow or else pay more for remaining the same.” Mailer was wounded by the bad reviews, but he struck back by collecting the worst of them into an advertisement he placed in the Village Voice, which he’d helped found that year.

Reading his way through Mailer’s work and Lennon’s biography, the YW found himself understanding for the first time Mailer’s response to the change in his fortunes. Though only a part-time Marxist, Mailer was a full-time dialectician, and he seemed to understand that passing from easy establishment success to this subsequent drubbing provided the opportunity for a synthesis out of which the real Norman Mailer might emerge. He wrote about the experience for Esquire in 1959, in “The Mind of an Outlaw,” the essay that lends its title to the new collection:

In a way there was sense to it. For the first time in years I was having the kind of experience which was likely to return some day as good work, and so I forced many little events past any practical return, even insulting a few publishers en route as if to discover the limits of each situation. I was trying to find a few new proportions to things, and I did learn a bit.

To judge each action by how much was learned and whether the experience was likely to return someday as good work — this in itself interested the YW, but it might as easily have been said by any number of novelists. More interesting was Mailer’s view of the larger culture he inhabited.

[W]hy then did it come as a surprise that people in publishing were not as good as they used to be, and that the day of Maxwell Perkins was a day which was gone, really gone, gone as Greta Garbo and Scott Fitzgerald? Not easy, one could argue, for an advertising man to admit that advertising is a dishonest occupation, and no easier was it for the working novelist to see that now were left only the cliques, fashions, vogues, snobs, snots, and fools, not to mention a dozen bureaucracies of criticism; that there was no room for the old literary idea of oneself as a major writer, a figure in the landscape.

When the YW thought about the problems facing writers of his own time, he was likely to put things in nearly these terms. But it wasn’t the day of Fitzgerald and Perkins to which the YW and his peers looked with longing. They looked to Mailer’s day, the time of Partisan Review and the early Dissent, the time of Trilling and Barzun, the time when Mailer himself might be found on television beside Gore Vidal or William F. Buckley or James Baldwin. In the Fifties and Sixties, Mailer was assuredly a figure in a landscape.

“The Mind of an Outlaw” became a central component of Mailer’s 1959 collection of “pieces and parts, of advertisements, short stories, articles, short novels, fragments of novels, poems and part of a play.” Advertisements for Myself was the first of Mailer’s books to take the figure of Norman Mailer as its explicit subject and, not coincidentally, the first that struck the Young Writer as having achieved real greatness. That it had done so took the YW by some surprise, since it contained so much work that was manifestly no good, work its author seemed to know was no good — undergraduate juvenilia, Village Voice columns written in stoned haste. This very unevenness became part of the Mailer legend, a sign of his commitment to testing limits. We needed to see the man fall on his face once in a while to appreciate the risks he ran. “For those who care to skim nothing but the cream of each author, and so miss the pleasure of liking him at his worst,” he wrote in the note to the reader that opened Advertisements, “I will take the dangerous step of listing what I believe are the best pieces in this book.”

To skim in this way would have been a mistake, not just because Mailer wasn’t to be trusted to choose his best work, but because the book’s great breakthroughs were its “advertisements,” bits of interstitial polemic that explained the meaning of each selection and gave the whole both cohesion and narrative force. “Like many another vain, empty, and bullying body of our time,” Mailer began the first of these advertisements, already up to full speed,

I have been running for President these last ten years in the privacy of my mind, and it occurs to me that I am less close now than when I began. . . . In sitting down to write a sermon for this collection, I find arrogance in much of my mood. It cannot be helped. The sour truth is that I am imprisoned with a perception which will settle for nothing less than making a revolution in the consciousness of our time. Whether rightly or wrongly, it is then obvious that I would go so far as to think it is my present and future work which will have the deepest influence of any work being done by an American novelist in these years. I could be wrong, and if I am, then I’m the fool who will pay the bill, but I think we can all agree it would cheat this collection of its true interest to present myself as more modest than I am.

The YW could see that much work was being done here to establish the figure. But work was likewise being done to establish the landscape: Advertisements for Myself inaugurated the Mailer staple of taking candid stock of his competition, which he does in an essay called “Evaluation — Quick and Expensive Comments on the Talent in the Room.” He begins with James Jones and William Styron, two contemporaries he counted among his closest friends. To each he is alternately generous and devastating. From Here to Eternity is “the best American novel since the war,” but Jones’s subsequent work has been a “debacle.” Like Jones, Styron “may have been born to write a great novel,” but “his mind was uncorrupted by a new idea.”

More than a dozen other novelists get similarly mixed treatment. Breakfast at Tiffany’s is a “small classic,” but Capote “has less to say than any good writer I know.” Despite an absence of “discipline, intelligence, honesty and a sense of the novel,” Kerouac “had enough of a wild eye to go along with his instincts and so become the first figure for a new generation.” On Bellow: “knows words, but writes in a style I find self-willed and unnatural.” On Salinger: “the greatest mind ever to stay in prep school.” On Ellison: “essentially a hateful writer: when the line of his satire is pure, he writes so perfectly that one can never forget the experience of reading him.” On Baldwin: “too charming a writer to be major.”

“Quick and Expensive Comments” concludes with Mailer’s earliest and most famous expression of literary misogyny, a confession that he hasn’t included any women in the essay because he doesn’t like the “sniffs” of women’s ink; “a good novelist,” he concludes, “can do without everything but the remnant of his balls.” While the YW found it possible to read Mailer’s later antifeminism in an interesting light — as an effort to find a stream in the culture willing to oppose him with the full adversarial force he required — no such defense could be made here. But it occurred to the YW that radical honesty wasn’t worth much if all one’s secret opinions were finally defensible. What passed for candor in the YW’s era had something self-serving about it. One made confessions with the attendant expectation of forgiveness. Or one expressed opinions only to psychologize or sociologize them away, so that reader and writer were left in the same comfortable liberal consensus. When Mailer told us his opinions, he allowed that they might be wrong, but he made it clear that he didn’t think they were wrong; that’s why they were his opinions.

The YW was tempted to say that what his own landscape lacked was Mailer’s willingness to offend, but this put the emphasis in the wrong place. Mailer was at his worst when he was obviously hoping to offend, as in his riff on women’s ink. Anyway, there were plenty in the YW’s time willing to say stupid things merely to get attention. But Mailer at his best simply told the truth as he knew it, whether it offended or not. And this was a rarer thing. The YW was among those who thought his own landscape was too nice when it came to hard truths, too cozy. Some said this was because the cost of harshness had become too high: writers could no longer depend on sales alone to support themselves, and the object of one’s criticism might be in a position to weigh in on a tenure decision or the awarding of a fellowship. But what were tenure and fellowships when one believed, as Mailer did, in the possibility of a revolution in the consciousness of the time?

Sometimes the YW imagined a political journal that covered only politicians it liked: With so many fine, underappreciated candidates out there, what was to be gained by tearing someone down? It sounded absurd precisely because everyone agreed that politics mattered. A bad candidate could do real damage if elected. So, too, the YW thought, could a bad novelist, especially if mistaken for a good one. Naturally he longed for the time when this had been widely recognized.

But hadn’t Mailer himself complained of cliques, fashions, vogues, and fools? It was difficult for the YW to imagine a famous writer of his own day putting on a performance like “Quick and Expensive Comments,” but no famous writer other than Mailer would have done it back then, either. And few had known what to make of it. Lennon reports that James Jones kept a copy of Advertisements in his apartment in Paris; when writers mentioned in the essay came through town, he would ask them to write comments in the margins. Only Gore Vidal seemed to take the book in the spirit in which it was offered, writing a mostly appreciative review in The Nation before proceeding to feud with Mailer for the next four decades.

By writing the contextualizing essay the critics of his day had failed to provide him, Mailer created the excitement he’d decided was missing. At least if he did it himself, he got to set the standards. And Mailer’s standards were clear: it was all about the big book. “[I]t may be better to think of writers as pole vaulters than as artists,” he claimed in another of his talent-in-the-room essays.

The man who wins is the man who jumps the highest without knocking off the bar. And a man who clears the stick with precise form but eighteen inches below the record commands less of our attention.

Mailer knocked the bar down as often as any great writer the YW could think of, but he never set the bar where it could be easily cleared. He explained in Advertisements that The Deer Park had been “conceived as the first book of an enormous eight-part novel.” The collection included the prologue to this already abandoned project, “The Man Who Studied Yoga,” as well as the prologue to the next long novel, adding that “one of the purposes of this collection is the intention to clear ground” for the novel.

“Several times over the next half century,” Lennon notes, “he came up with ambitious, skeletal plans for multi-novel projects as a way of getting started on the next one.” When he did publish another novel, it bore no resemblance to the long novel described in Advertisements. Instead it was a short book about a famous public intellectual who drunkenly murders his wife. An American Dream was written on deadline and serialized in Esquire, an arrangement that not only paid Mailer well but also allowed him to present the book as more freelance work, signaling to his audience that it shouldn’t be judged against the standards of the big book. It was followed by Why Are We in Vietnam?, which similarly declared its minor status. The book’s author photo shows Mailer in full self-mythologizing mode, wearing a shiner and aching for a fight, and the jacket copy says the short novel appears “between the longer works he has written in the past and the longer works he will produce in the future.” The book was well received at the time, but it read to the Young Writer like a throwaway.

The period that followed, from 1968 to 1979, was the peak of Mailer’s career. But his success didn’t come from the publication of the big novel, or of any novel. Mailer solidified his standing as America’s most important novelist without publishing any new fiction at all.

Shortly after the appearance of Why Are We in Vietnam?, the novelist Mitchell Goodman invited Mailer to participate in an antiwar march to the Pentagon. Over the course of a weekend in the capital, Mailer gave a drunken speech at the premarch rally, described by Time as an “unscheduled scatological solo,” and was later arrested for crossing a police barrier at the march itself. On his return to New York, he realized he’d done the thing he’d most desired to do, which was to play an important role in an event of real cultural significance: the March on the Pentagon was the moment the antiwar left became undeniably powerful, and Mailer was a part of that moment. He had not attended as a journalist, but he knew he needed to write about the experience, and his agent negotiated a $10,000 contract with this magazine. “The Steps of the Pentagon” ran in the March 1968 issue at 85,000 words, then the longest magazine piece ever published in America.

Mailer approached the material as a novelist; when a slightly longer version appeared in book form as The Armies of the Night, the work bore the subtitle History as a Novel, The Novel as History. Mailer decided that to “resolve . . . the ambiguity” of the event, he needed “an eyewitness who is a participant but not a vested partisan . . . not only involved, but ambiguous in his own proportions, a comic hero.” That he hit upon himself for this role was predictable. The real breakthrough was his decision — inspired in part by The Education of Henry Adams and in part by Mailer’s recent work in film — to depict himself in the third person, as the literary character “Norman Mailer,” a perspective Lennon calls the “third person personal.” It allowed Mailer to insert some distance between the participant and the novelistic intelligence. It also allowed him to write about the Mailer legend even more successfully than he had in Advertisements.

“He had in fact learned to live in the sarcophagus of his image — at night, in his sleep, he might dart out, and paint improvements on the sarcophagus,” Mailer writes early in The Armies of the Night.

During the day, while he was helpless, newspapermen and other assorted bravos of the media and the literary world would carve ugly pictures on the living tomb of his legend.

The reason this works is that his treatment of the figure in the landscape required as much attention to the landscape as to the figure. There are expert renderings of every subsection of the antiwar left as it existed at the time — from hippies to civil rights leaders to Ivy League chaplains — and of other literary figures at the march, including Dwight Macdonald and Robert Lowell. In one scene, Lowell tells Mailer, “I really think you are the best journalist in America.”

“Well, Cal,” said Mailer, using Lowell’s nickname for the first time, “there are days when I think of myself as the best writer in America.”

The effect was equal to walloping a roundhouse right into the heart of an English boxer who has been hitherto right up on his toes. Consternation, not Britannia, now ruled the waves. Perhaps Lowell had a moment when he wondered who was guilty of declaring war on the minuet. “Oh, Norman, oh, certainly,” he said, “I didn’t mean to imply, heavens no, it’s just I have such respect for good journalism.”

“Well, I don’t know that I do,” said Mailer. “It’s much harder to write” — the next said with great and false graciousness — “a good poem.”

Lennon reports that it took Mailer “half the book before he adjusted psychologically” to the third-person personal. The Young Writer could well understand this difficulty. But the method succeeded completely for Mailer, and it became his preferred approach to non-fiction. Harper’s quickly sent him to the 1968 Republican and Democratic presidential conventions, and the result was Miami and the Siege of Chicago. Both books were nominated for National Book Awards the following year. The Armies of the Night won the Award for Arts and Letters, along with the Pulitzer Prize for General Nonfiction.

For the next decade, Mailer gave the better part of his writing life to a series of non-fiction books written in this third-person personal. He took on the moon landing, the 1972 presidential campaign, feminism, the heavyweight championship fight between Muhammad Ali and George Foreman. From book to book, the third-person figure shifted; it might be “Mailer” or “Norman” or “the Novelist.” In Of a Fire on the Moon, he calls himself “Aquarius,” which the YW thought would be merely ridiculous but somehow wasn’t. The Prisoner of Sex, his attack on feminism — or, rather, his rebuttal to feminists’ attack on him — begins, “Near the end of the Year of the Polymorphous Perverse (which is to say in the fall of ’69) there were rumors he would win the Nobel.” From there on, Mailer is “the PW,” which stands alternately for “the Prizewinner,” “the Prisoner of Wedlock,” and “the Prisoner of War.” During this time Mailer created the sense that no major story had been settled until it had received the Mailer treatment, and he always found a way to bring things back to his favored themes — the coexistence of God and the Devil; the inevitability and even nobility of violence in response to powerlessness; the dangers of technology; the essential differences between the sexes.

All these books were first published as long magazine pieces — The Prisoner of Sex nearly filled an entire issue of Harper’s. Mailer took on this work in part to support his ever-expanding household. (By the mid-Seventies he was living with the woman who would become his sixth wife, though before he married her he needed to divorce his fourth, then marry and divorce his fifth; he had children with each of them.) These financial demands were very real, but it seemed to the YW that ultimately Mailer’s desire to be a great novelist and his desire to be a significant cultural figure were at odds with each other.

In the early Seventies, Mailer started a new “big book,” the “Egypt novel,” an account of the reign of Pharaoh Ramses IX. “He knew it was time to write the novel of his life,” Lennon says, “or give it up and be satisfied with the primacy first accorded him by Robert Lowell: the nation’s finest journalist.” Mailer wrote hundreds of thousands of words of it throughout the decade. But then he was distracted again by non-fiction. In early 1977, Larry Schiller, a photographer with whom Mailer had collaborated on a few previous books, contacted him to say he’d bought the rights to Gary Gilmore’s story and wanted Mailer to work with him on it.

Gilmore had been killed by firing squad a few days earlier for murdering two people in Utah; he was the first person executed in the United States since the end of a four-year moratorium on the death penalty imposed by the Supreme Court. His story was a tabloid sensation, and Schiller had paid Gilmore and his family $60,000 for access. He and Mailer eventually sold the story to Warner Books for $500,000.

Because Mailer came on board after Gilmore’s execution, and because his source material consisted of reams and reams of Schiller’s interview transcripts, it wasn’t clear how he could work his usual authorial stand-in into the plot. At first he created a fictional character named Staunchman who could act like the Mailer figure in his other books. When this didn’t work, he rewrote what he had with a conventional, third-person narrator.

The Executioner’s Song contains all of Mailer’s big themes, and it is a remarkable act of ventriloquism, featuring hundreds of voices, none of them Mailer’s own. This last fact is often noted as an irony, but it struck the Young Writer as a typical example of Mailer’s canniness. Absence is only meaningful when presence is expected. The second half of the book, “Eastern Voices,” is largely concerned with the media response to the fight over Gilmore’s execution — Schiller makes a prominent appearance. We await Mailer and are surprised when he never arrives. As an act of selflessness, it seemed to the Young Writer somewhat like Wilt Chamberlain setting out one year to lead the league in assists instead of points.

Mailer called The Executioner’s Song a novel, though it was the most meticulously documented of his reported narratives. Lennon expends much energy puzzling over this decision, but to the YW it seemed likely that Mailer understood that he’d taken his best shot at the big book, and the big book had to be a novel. It was his only work to win a major award in a fiction category — his second Pulitzer — and its publication was the last unmitigated victory of Mailer’s career. The victory created a dilemma. If he had now gloriously exhausted a certain vein of non-fiction writing, there was nothing left but to return to fiction, which was after all the real work. He’d sprung a trap of his own devising. For a decade he’d been paid a monthly advance to write the Egypt novel, and now he was expected to deliver. He called the rush to finish “a perfect expression of my character: work ten years with great care on something, and then arrange matters so that I have to sprint at the end.”

Ancient Evenings received Mailer’s worst reviews since The Deer Park — which is to say, since Mailer had last written a long novel. Unlike those earlier assessments, these struck the YW as fair: the book is a bad book — overlong, overly scatological, and absurd beyond any possible intention. In any case, Mailer understood that it wasn’t going to alter anything but his reputation and that it wouldn’t make a dent in the consciousness of the age.

Mailer would commit himself to fiction in the remaining years of his life, but he seemed almost to have lost the basic capacity for novelistic invention. He could apply his imagination to the facts as he found them, but he couldn’t really fictionalize. Instead he wrote a series of painstakingly researched historical novels. The only purely fictional work was Tough Guys Don’t Dance, a paint-by-numbers bit of hackwork, written at speed for money.

While reading The Mind of an Outlaw, the Young Writer decided that even the great essays from Advertisements and The Presidential Papers and Cannibals and Christians didn’t work nearly as well in this volume, a curious sign of how much Mailer’s power depended on the context he created for himself. Mailer’s effort at creating that context never let up entirely. He kept to his habit of taking on the talent in the room. In particular, he liked to speak up whenever it seemed that a younger male novelist might have made a shot at the big book. He worked them over in the same spirit with which he’d once worked over his peers, mixing admiration with disappointment. He wrote a long review of American Psycho in which he acknowledged Bret Easton Ellis’s talent — “How one wishes he were without talent!” — before noting that “we cease believing that Ellis is taking any brave leap into truths that are not his own. . . . [H]e is merely working out some ugly little corners of himself.” A review of Jonathan Franzen’s The Corrections called it “very good as a novel, very good indeed, and yet most unpleasant now that it sits in my memory.” He added speculation that recalled his own situation after The Naked and the Dead:

Now, the success of The Corrections will change his life and charge it. Franzen will begin to have experiences at a more intense level; the people he encounters will have more sense of mission, will be more exciting in their good and in their evil, more open at their best, more crafty in their use of closure. So if he is up to it, he will grow with his new experiences (which, as we ought to have some idea by now, is no routine matter), but if he succeeds, yes, he has the potential to become a major writer on a very high level indeed.

In the event, of course, Franzen did almost the opposite. Rather than exploring his own celebrity he retreated from view for the better part of a decade to work on the next big book.

At the time, the Young Writer had admired Franzen for it, but now he wasn’t so sure. After the suicide of Franzen’s closest literary friend, David Foster Wallace, discomfort in the world seemed less like an aesthetic principle than a form of pathology, or at best a defensive response to the possibility that the novelist was no longer an important figure in the landscape. It changed things for the YW to know that Mailer had been faced with the same possibility half a century earlier, and that he had responded not with a retreat but with an attack.

In 1994, Mailer complained that the place in the culture once reserved for the novelist had come to be occupied by Madonna. The YW would say that in his own time this place belonged perhaps to Kanye West, but that Kanye more or less deserved that place, insofar as he had not just talent but Mailer’s fascinating combination of megalomania and vulnerability, Mailer’s willingness to make a fool of himself, Mailer’s belief in his own importance, and Mailer’s determination to take the case for that importance straight to the people. The YW remembered what Schiller (the German poet, not Mailer’s buddy) had said — that a man must be a good citizen of his age, as well as of his country. What the literary world needed was a few good citizens willing to tell the age tough truths.

Instead, it had the writer as philanthropist (Dave Eggers), the writer as borscht-belt clown (Gary Shteyngart), and, worst of all, the writer as graduation speaker. Somehow the graduation speech — usually a genial collection of uncontroversial clichés — had become the great literary form of the day. The one Wallace gave at Kenyon College — certainly among the least interesting or challenging things he ever wrote — became his signature work. George Saunders, who had replaced Wallace in the role of the writer as secular saint, had recently spoken to the graduating class at Syracuse and told them to be nicer to one another. It was a fine idea — not for nothing had Jerry Springer once ended each broadcast with a similar sentiment — but it hardly seemed worth publishing as a stand-alone book. Doubtless when it is so published it will be bought for every graduate in the land, outselling everything else Saunders will ever write.

Occasionally writers managed quite by accident to cause offense, but when they did they responded with great contrition. The YW had cheered when Jennifer Egan — a novelist he had long taken as a model — said that young writers ought to aspire to something better than “banal and derivative” commercial fiction. But after the remark hurt the feelings of banal-and-derivative-commercial-fiction writers, Egan had made a public apology, seeming genuinely horrified. It had bothered the YW that Egan retreated just when she seemed on the edge of insisting, as Mailer had insisted, that there was something unique to be gained from a great novelistic intelligence applied to its age, that such a performance was more valuable than the entertainment provided by commercial page-turners or prestige television dramas, that it was, for that matter, more valuable than literary fiction that lacked the same ambition. Because this news was not welcomed by mediocrities, and because mediocrities have feelings, Egan had felt forced to withdraw the remark.

But perhaps the YW was wrong to wait for someone else to lead the way, to expect someone to prepare the landscape for him. When it came down to it, the Young Writer wasn’t all that young anymore. If his own time did not appear so inviting, perhaps it was his job to do something about it.