There was a game we played. Maybe it wasn’t a game in and of itself. Is a ball a game? A ball is not a game. But you can make a game with it, can’t you? What can’t you make a game with or of? You just have to decide you’re going to do it, is all. Or not even make up your mind and go ahead and decide as such. All you have to do is take the thing and start doing something with it and then say to a boy on the block, Can you do this? and then you show the boy that you can, and then the next thing is that that particular boy has to see if he can do it too or even if he can’t, well, I ask you, is there or is there not already enough of a game going from just that much of it already? Or even better, let’s say he can’t do it, the boy, that particular boy, then even better, even better that he can’t, except who can say, maybe before you know it you’re the boy who’s sorry you started the whole thing in the first place, because maybe the boy we’re talking about, maybe he can go ahead and do it better than you can do it, and then you wish you had never even taken the reins and started the game and could instead of any of that just stop playing it, but you can’t stop playing it, because every time that particular boy on the block comes around he’s got the thing you need for the game with him and he says to you, Hey look, can you do this, can you, can you? even if all you have to do is do it as many times as he can, or do it a little farther than he can, or do it faster than he can, or, you know, more times, or do it some other way different like that.

It was like that when I was a boy.

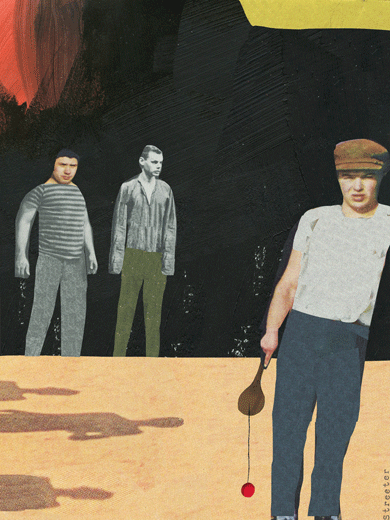

So the thing itself in the case I am thinking about, it was a little red ball — and there was this mysterious way they had of getting the little red ball stuck to a pretty long red rubber string, and the string, this pretty long red rubber string, was stapled to a paddle, that was the thing I want for you to picture for yourself, the paddle and the ball and the string — are you with me? — the paddle and the ball and the string, which the whole idea of the game was for you to grab the paddle in your hand and see if you could toss the little red ball up a little bit and then smack it with the paddle and then keep on smacking it with the paddle until you missed it altogether or, you know, you just didn’t smack it right and it went all crazy in the wrong direction and then it was the other boy’s turn, or if there were a lot of other boys, which was the way it just so happened to be on my particular block, even at this day and age I could name every one of the boys if you dared me to, if you happened to want to take the time it would take for me to go ahead and look back in my mind and name every single last one of them or, okay, maybe if truth be told, maybe I wouldn’t be absolutely able to name every last one of them, but you can bet your bottom dollar I could probably name plenty enough of them for me to give you the general drift of the thing I am taking the trouble to sit here and tell you about, such as the Stanleys, for instance, such as the Stanleys themselves, who were, for your personal information, the biggest of all of the boys on the block and who I wouldn’t at this particular point in history be the least little bit surprised if they were probably the oldest of all of us too, Stanley R. Florin, for instance, and Stanley S. Baughman, for another instance. That’s right, I’m right, those were the two Stanleys, Stanley R. Florin and Stanley S. Baughman, they were referred to as the Stanleys, or as the two Stanleys, and they were pretty good at the game, let me sit here and tell you that the two Stanleys, that they were pretty goddamn terrific at it, yes indeedy, I am here at this point in history to goddamn tell you the Stanleys were good, the Stanleys were great, the two Stanleys were the best at the game of anybody on the block, them just going ahead and taking the paddle from you and then smacking the little red ball with it and then just keeping on smacking the crap out of it and then on and on and, wow, holy cow, making the little red ball come whipping right back at the paddle to smack the shit out of it all over again and then smack it some more and keep smacking it some more and, you see, you see, just look at it, are you really trying with your mind to look at it, either one of the Stanleys just smacking that little red ball every time the long red rubber string goes snapping out and then comes snapping back at the paddle again — and then again and then again and then this way and that way until, Jesus, who could stand there and believe it anymore, until you just had to stand there praying and hoping and hoping and praying your turn was never going to come up again, but no matter how much you stood there pleading with Jesus himself, you pleading with Jesus, Please, Jesus, please don’t let it, don’t, don’t, please don’t let my turn come again, please, Jesus, please, but it would, oh you bet it would, and there you were, standing there with the vicious paddle, ashamed all over again and sad, so sad, so awful sad from just standing and standing and from hearing yourself screaming out loud to yourself inside of yourself for it all of it to be all over and finished again, please, for it all of it to stop, just stop, just for it to break and be broken, string gone, ball gone, paddle flown out of your hand, and for everybody, for all of the boys, for them just to fall over and finally be dead.

Oh Jesus, your turn!

Oh Jesus, my turn!

Oh me, I’m telling you, I myself as a boy, I’m telling you, I’d go ahead and take the handle of it in my hand and go ahead and give the little red ball a little bit of a toss, but try as I might, and I tried, oh brother, boy oh boy, did I for Christ’s sake try to just get the little red ball to go up and come back down just even twice for once, even if I hit it just as easy as pie, just only straight up and right straight back down to the paddle just twice for once.

But Bobby, there was a boy Bobby, I don’t think I told you anything about this particular boy Bobby yet — because there was this particular boy Bobby on the block, and Bobby was worse.

I’m serious.

I’m being serious with you — there was this Bobby, okay, and believe you me when I tell you, this boy Bobby was worse, this boy Bobby was probably even the worst of all of the boys — until, wait, wait, you didn’t hear anywhere near anything yet where the rest of this thing is going to come out to its honest-to-God ending yet, you don’t even know the first thing about any of the whole unbelievable miracle of this particular story yet, the worst boy on the whole block, the worst, the worst, this Bobby, this Bobby, doesn’t the day all of a sudden dawn, doesn’t the day all of a sudden come along when this Bobby who I have been mentioning to you, when this particular boy Bobby, he all of a sudden starts taking the paddle and beating the piss out of the little red ball, which, like I told you, like I already took the time to tell you, which was stapled to it, just standing there like it was nothing to him if he hit it this way or if he hit it that way because whichever way this boy Bobby wanted to hit the little red ball he hit it and hit it just the way I just have been mentioning to you, the weakest, the littlest, the worst boy on the block, but wait, wait, what happens but the day fucking dawns, the day just fucking comes fucking along when, hey, hey, this boy Bobby, he’s taking the paddle and smacking the little red ball better even than Neal could and better even than Clive could, and you take Clive, or you take Neal, those two boys, those two particular boys, they themselves were almost themselves in a league with the two Stanleys, it’s true, I mean it, it happened just the way I just sat myself down here and just this minute have been telling you, this Bobby passing this Clive by and then this Bobby passing this Neal by and then this Bobby almost catching up right there in front of your eyes to one of the Stanleys once, this boy on the block Bobby himself almost catching up right there in front of your eyes to one of the two Stanleys once, this boy on the block Bobby almost catching up to Stanley S. Baughman once or with, or to, the other one of the champs once, to, or with good old Stanley R. Florin once, but definitely with one or to one or the other of them once.

That’s right, that Bobby, he was almost right up there with one of the champs once — and then that particular Bobby boy, he just, zowie, he just keels over and dies from something, or of something, like of something like spinal meningitis probably, or maybe it was instead from, you know, from polio instead, this particular boy Bobby who himself was just like a miracle in and of himself all so all of a sudden suddenly at once.

So that’s when I had no choice but to invent the game of getting a stick and hitting a pebble with the stick, but not just hitting the pebble with the stick but hitting it right straight at the face of a boy on the block and — wait, wait — because I mean hitting the pebble with all of your might, that’s right, hitting it with all of it, hitting it with absolutely all of it, like every boy who was ever in his heart a boy who knows things right down to the soles of his shoes, there’s this feeling — right? — there’s this thing you have to have for you to have a feeling like this, which is this really type of mysterious feeling of it or for it, like of or for you giving the pebble one of these really great whacks, like whacking it solid in the center of the stick like, I mean like whack, whack, I mean like cracking it right with the right part of the stick, which was just how it was when this particular boy on the block whose name I happen at this particular juncture to think was probably a name like Edwin probably or maybe more like Everett, I think, or like some other terrible name like that, like a name probably beginning with this horrible letter E in front of it, I think, which it is my personal official opinion that I have already made fair and ample reference to, but hold it a minute, just hold it for one little more minute, because, yes, yes, Elliot, wasn’t it, or spelled Eliot or instead Eliott or something E-name-wise like that?

It put his eye out just the same.

Whichever eye it was, whatever name it was.

He cried a lot with his sight knocked out like that and then he had to go all around all over the block with this drippy-looking bandage hanging half over the whole seepy mess of it, and this — me sitting here as God is my judge — this very thing was what this poor particular unfortunate boy had to do for years and years to come, until, thanks to the regular fabulous improvement you can always count on with regard to our modern-day medicine, he got to be old enough and got himself more settled down in his emotions enough for the experts to go ahead and give him an operation and put a ball of something in there where a real eye used to be for like this fake one to be there in his head instead.

Oh, I know, I know.

Wrong, wrong! — of course I was wrong.

I completely forgot to remember that it was Henry — that it wasn’t even close to any E-name but that it was a particular name — Henry, Henry! — which I, Gordon, personally hated the guts out of.

And here’s another thing for you to sit there and take into your thoughts in the process of according to them the consideration due them while you and your family marvel over these long-ago personal events that I, Gordon, am taking the trouble to tell you about, that it took two days — two! — for the boys on the block to get somebody’s mother’s broom cut clear away all of the way off from its handle so that, in effect, you had yourself a free-swinging stick that you could really lay your back into and then — wait, wait! — two more days on top of those two days, this crazy thing of this number of two again — right, am I right? — the mystery of it, the fucking mystery of it, Jesus! — it taking two more days on top of that for us to get the handle sawed off short enough so that you could really stand there and have the presence of mind for you to develop this particular feeling for yourself of getting your feet planted just exactly right enough and really wind that fucking half of a handle up with all of your might and lay your whole young back into it, really get your whole great-feeling boy’s back heaved all of the way into it and wing that son-of-a-bitch pebble out there into anybody’s face you felt like just like a fucking shot like.

But so what?

I mean, I ask you, did it matter, what did it matter, whose eye you could maybe put out?

I mean, come on, hadn’t we all of us already seen what wasn’t all of it just only — everything, everything! — just only a different type of a game where there was nothing — nothing! — not anything on all of the whole block that was really on the up-and-up?