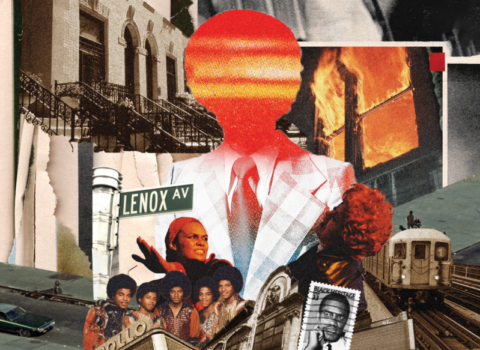

Discussed in this essay:

The Tastemaker: Carl Van Vechten and the Birth of Modern America, by Edward White. Farrar, Straus and Giroux. 400 pages. $30.

The reputation of the New York writer and salonnier Carl Van Vechten is best cherished today, almost in spite of what he published in his lifetime, in departments of African-American studies. From the 1910s through the 1940s, Van Vechten was the most outspoken white go-between connecting black performers and writers to the New York City press. He helped launch the careers of Paul Robeson and Langston Hughes at more or less the same time, in the mid-1920s, and even before that he systematically brought the rhythm of the blues to American high culture. Van Vechten also meticulously photographed American artists from the 1930s until his death, in 1964 — especially black artists, anticipating the country’s growing fascination with both visual culture and its multiracial identity. But for a well-to-do white man who wrote best-selling fiction and was a key delineator of American modernist tastes in music, art, dance, and literature, Van Vechten’s designation today as a “Negrotarian,” as Zora Neale Hurston once called him, is very nearly a defeat.

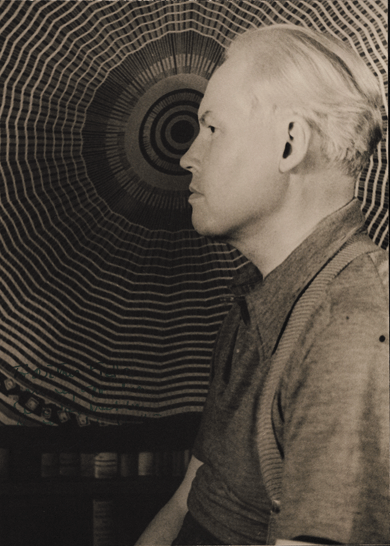

“Carl Van Vechten in profile,” by Carl Van Vechten. Courtesy Carl Van Vechten Papers,

Yale Collection of American Literature, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library

Van Vechten, who in an unpublished piece of college prose wrote that when he crashed turn-of-the-century black American circles in Chicago he was “invariably taken for a coon” (by other “coons,” that is), has finally crossed the color line. His reputation, affected perhaps by his personal character — hedonistic and whimsical, grandiloquent and narcissistic — has suffered the behind-the-scenes fate of his adopted people, the same fate reserved for such musicians as Louis Armstrong, Duke Ellington, and Charlie Parker and for the novelists Ralph Ellison, James Baldwin, John Edgar Wideman, and Toni Morrison, among others. Despite the renown and critical purchase of these artists, the real powers in American cultural life consider them a tad purplish when they start blowing — virtuosic but vain, overindulgent if spirited, campy and straining. They shine the penny too brightly, blurring the distinction between fad and tradition.

Van Vechten lived the kind of life outside the lines that appeals to Americans and Europeans today as romantic and devil-may-care. Edward White, in his breezy and enjoyable new biography, argues that Van Vechten was quintessentially American — that is, part entrepreneur, part inventor and pragmatic innovator, and part sideshow gimcrack barker. “Famous for his frivolity and elegance,” Van Vechten possessed modest gifts but excelled in his willingness to make a splash, to prick convention. And his adult life coincided with one of the most artificial public conventions established in the modern Western world — Jim Crow segregation, which reached its peak in the mid-1920s, when Van Vechten himself approached his full power. It isn’t hard to see Van Vechten, when pitted against such strident racism, as a kind of color-line-bending shaman. But Van Vechten did not create multiracial America; he simply recognized what was already there. His courage derived from his willingness to battle, with such weapons as he had, the whitewash under way during the first half of the twentieth century.

Born in 1880 into a Cedar Rapids, Iowa, family who had migrated from Holland to New Amsterdam in the middle of the seventeenth century, Van Vechten grew up in a household of successful businesspeople who had a taste for the arts and social reform. Van Vechten’s father helped fund the Piney Woods School, an institution of African-American education in Mississippi that stands today. Carl was raised to address the family’s black servants by their surnames, with Mr. or Mrs. as prefix. He attended the University of Chicago, where he only flirted with the classroom, preferring to spend his down time in two of the city’s other institutions. First was the Auditorium Theatre, home of the Chicago Orchestra and the Chicago Opera and the domain of the conductor Theodore Thomas, who was determined to bring the gospel of Wagner, Dvorák, and Richard Strauss to the bloated slaughterhouse town. Second was the Levee, a place White calls “the most depraved locale of any city in the United States.” (To win that laurel in Van Vechten’s time you had to beat out Storyville in New Orleans, Beale Street in Memphis, and the Baltimore of one Clarence Halliday.) Along Satan’s Mile — in places like the Bucket of Blood, the Why Not?, and, Van Vechten’s favorite, the Everleigh Club — brothels catered to all manner of carnal appetites.

“Billie Holiday with ‘Mister,’ ” by Carl Van Vechten. Courtesy Carl Van Vechten Papers,

Yale Collection of American Literature, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library

Van Vechten put on galoshes after graduation and waded into the muck of crime reporting for Hearst’s newspaper the Chicago American, but his love of fine art kept him attuned to chances farther east. He parlayed his acquaintance with Theodore Dreiser into a staff position at the New York Times in 1906, soon announcing himself as the critic who dared to applaud the Metropolitan Opera’s production of scandalous, skin-baring Salome. From there he moved to Paris, flubbing a job as an international correspondent but acing the town’s nightlife scene, before returning to New York to write articles in praise of the dancer Isadora Duncan. After a failed marriage to a Midwest socialite (which fell apart either on account of Van Vechten’s affair with the playwright Avery Hopwood or because of a child given up for adoption), Van Vechten became one of the regulars at Mabel Dodge’s salon on Fifth Avenue. The salon’s storied theme evenings, on such topics as Cubism, “sex antagonism,” psychoanalysis, and revolutionary socialism, attracted intellectuals, political activists, and artists. One night, Van Vechten brought a black burlesque vaudeville act to the all-white salon, and he laughed, clapped, and emitted “little shrieks” while the banjo played and the hostess’s temperature flashed hot and cold in discomfort. The elegant bohemians were delighted to wax philosophical about the illicit cabaret clubs of the Tenderloin, but when Van Vechten served them up raw black music and sensuality, the people from his set tended to faint. Van Vechten enjoyed the fainting, the power he had to cause people to convulse and suspire.

Van Vechten’s exuberance for black bodies had begun in a stereotypical way. “How the darkies danced,” he blared in his early critical sallies from the 1910s. “Delightful niggers, inexhaustible Ethiopians, those husky lanky blacks!” Slumming gave him a drunken titillation. He so habituated the tables of the black performers’ Midtown mecca, Marshall’s Hotel, that he was depicted in Charles Demuth’s 1918 painting Cabaret Interior with Carl Van Vechten. But pleasure soon began to take him in the direction of principle. Before the end of the 1910s (and in the company of the tireless iconoclast H. L. Mencken), Van Vechten started to argue for the primal strength of American culture, especially African-American culture. He heartily promoted Ridgely Torrence’s play Granny Maumee, with its all-black cast, because it exemplified the use of “the negro or the Indian or something that fully belongs to us.” He encouraged black singers such as Bert Williams, who could turn the minstrel jokes on whites, and acted as both publicist and deal-maker for the captivating songstress Ethel Waters. He believed instinctively in ragtime, the blues, and jazz, and he valued his friendship with W. C. Handy, who transcribed the first blues songs, copyrighted the earliest lyrics, and composed that jam of all jams, “St. Louis Blues.” “Americans are inclined to look everywhere but under their own noses for art,” Van Vechten yapped in 1917, well satisfied with everything he could sniff nearby.

He derived special pleasure from the clash of black life with high art. It was Van Vechten who introduced the cadenced, undulating prose of Gertrude Stein to American audiences, in his 1914 Trend magazine article “How to Read Gertrude Stein”; who praised the Armory Show the year that Nude Descending a Staircase was exhibited; and who claimed to have brawled for the love of art at the Paris premiere of Stravinsky’s Le Sacre du printemps. (He was there for the second night’s performance.)

This brand of swashbuckling modernism was not without its faults. In 1914, seemingly unmindful of the slaughter of World War I, Van Vechten wrote the glibly titled essay “War Is Not Hell,” which argued that such conflict was actually a creative force. Causes that required grim obligation to the poor — like communism when it came along, and even organized civil rights, both passions of many of his dearest friends — bored him.

Van Vechten was, at least for his time, outwardly if not quite flamboyantly gay and attached to a circle of young gay men he called the “jeunes gens assortis.” But Van Vechten neither bore a stigma nor shouldered a placard. Instead, he preferred a heterosexual domestic arrangement (and sometimes heterosexual sex) with the actress Fania Marinoff, who remained more or less by his side for fifty years.

Though Van Vechten had published multiple collections of essays on art and music in the first decades of the century, it wasn’t until his debut as a novelist, in the early 1920s, that he reached popular fame with American audiences. Celebrity, wealth, and scandal arrived with his second novel, 1923’s The Blind Bow Boy, a nearly outright story of sexual education whose popularity may have contributed to the so-called pansy craze that swept Manhattan a few years later. The hit was followed within a year by The Tattooed Countess (the middle-aged, sexually adventurous heroine has que sais-je? stenciled on her wrist), in which Van Vechten lampooned the provincialism of the same Middle America that had produced him.

In the 1920s, Van Vechten’s apartment, at 150 West 55th Street, became the headquarters of New York’s bibulous conviviality. George Gershwin couldn’t be moved from the piano (excepting one evening when Van Vechten wanted to play; the publisher Horace Liveright soon pushed “Carlo,” as friends called him, off the bench, breaking his shoulder in the process). Guzzling high-proof bootleg whiskey, dancing the Charleston, and crossing the color line were the articles of faith at Van Vechten’s cabaret, where he suspended, according to White, “the byzantine rules of racial division that existed beyond his front door.” (Carlo might have been better off leaving some of those rules unsuspended. After one party, a drunken Bessie Smith mistook Fania’s theatrical parting kiss for a come-on and knocked her to the floor.) The raucous festivities could not have survived without the sound track. “Jazz may not be the last hope of American music, nor yet the best hope,” wrote Van Vechten in 1925. “At present, I am convinced, it is the only hope.”

Van Vechten was onto something about the value of autochthonous culture, and his taste matured in 1924, when he read the novel The Fire in the Flint, by the assistant secretary of the NAACP, Walter White. White’s book, which featured a black doctor as its protagonist, dealt vocally with the national scourge of lynching. From then on, Van Vechten began to see black culture as more than merely the unrefined ore of American music, theater, dance, and general élan vital; he also reckoned seriously with highly educated black American artists. (For his part, the very light-skinned White cherished the cross-racial friendship so much that he named his only son Carl.)

After 1919, all of Van Vechten’s tastes converged in one New York neighborhood. Harlem became his “all-consuming passion, the absolute center of his social universe.” But Van Vechten eluded the punishment that ruined the other modernist provocateurs, making them bitter or suicidal, utterly frivolous or expatriates, and hurtling them toward conservative orthodoxy as they turned gray. Perhaps the small fortune bequeathed him when his elder brother died, in 1927, helped him dodge the inevitable reckoning.

Without Van Vechten, we might never have heard great black American artists like Bessie Smith and Billie Holiday. He helped them span the gap from the margin to the center of culture, both by introducing them to publishers and entertainment-industry executives and by preparing the readership of places like the Times and Vanity Fair for black art. As White argues, Van Vechten’s best talent was doubly promotional: “a gift for recognizing and expressing the ineffable brilliance of an artist and a moment of performance and, in so doing, binding himself to their greatness.”

But not all black Americans were grateful to their well-placed cheerleader. When Van Vechten’s paeans to black culture appeared in Vanity Fair, the black poet Countee Cullen declared it wrong to read such homilies, since playboy Carl was only “coining money out of niggers.” Van Vechten could be an irksome friend to the Negro too. He was the kind of impatient man who believed that racial segregation in New York would collapse within a fortnight if blacks were only more daring. Calcified white Northern prejudice concerned him not even as an afterthought. He was warmly caring, but mainly about himself, and was capable of enormous callousness to others.

This latter flaw became especially clear in 1926, with the publication of an inflammatory novel that threatened to undermine many of the relationships Van Vechten had cultivated in the previous decade. In July of 1925 Gertrude Stein had written to Van Vechten from Paris, urging him to write the “nigger book” they had been discussing for some time. The next month Van Vechten stumbled upon a title, Nigger Heaven, the impolite sobriquet used to identify the balcony area in theaters where Jim Crow laws required African-American customers to sit. Van Vechten’s father, Charles, shortly before his death, advised his son to change the title so that he might indeed help “the race” instead of scandalizing it. Van Vechten decided to brazen it out, temporarily losing the goodwill of W.E.B. Du Bois and others but making a pile of money in the process. The Afro-American, a newspaper published out of Baltimore, encapsulated the precise wound in a reported snippet of conversation: “You mean to say a man went to people’s houses and accepted their hospitality and then called ’em nigger?”

On the other hand, the title was shrewd. The novel’s black characters — the libidinal sexpot Lasca Sartoris, the priapic gunman Scarlet Creeper, and the college nerds Byron Kasson and Mary Love, Europhiles denying their purportedly atavistic racial urges — were archetypes dipped in the problems of ethnic identity. The story itself is that of a love triangle, in which Byron jilts the frigid Mary in favor of Lasca, who gives him a taste of the real Harlem nightlife. Not being in good taste was key to Van Vechten’s strategy; he pandered to widespread prejudice with descriptions of characters as “pure black, with savage African features, thick nose, thick lips, bushy hair . . . eyes rolled back so far that only the whites were visible.” But he did not underestimate the ignorance of the white American “booboisie.” A couple of New York businessmen, finding themselves astounded to read about African Americans who had been to college and could read French, invited Van Vechten to give lectures on race relations. He declined, but Walter White was happy to collect from the well-heeled in his stead. At the end of the evening White was told, “The average white person knows nothing about the things which you have said here tonight which are set forth in Nigger Heaven.” Nigger Heaven also had more than a few black readers, in spite of, or because of, the controversy. “I have seen its pale blue jacket with its discreet white printing in more brown arms than I have ever seen any other book,” wrote the poet (and librarian) Gwendolyn Bennett.

After a late-1920s try at Hollywood turned into a misadventure (and a disaster for his drinking buddy F. Scott Fitzgerald), Van Vechten gave more attention to promoting Gertrude Stein. Beginning in the fall of 1934 he led Stein on a triumphant tour of packed auditoriums around the United States. The shepherd of the Lost Generation, who died in 1946, rewarded him by making him executor of her literary estate. (When her protégé Ernest Hemingway wrote that Stein “only gave real loyalty to people who were inferior to her,” he probably had Van Vechten in mind.) Throughout Stein’s visit Van Vechten took photographs, including a formidable shot of Stein with the American flag draped behind her. Now in his fifties, Van Vechten turned his attention to portrait photography. In his first year he made pictures of Henri Matisse, Eugene O’Neill, Frida Kahlo and Diego Rivera, Bill Robinson, and Georgia O’Keeffe. Later he would add Truman Capote, Gore Vidal, Norman Mailer, and Marlon Brando. At his studio apartment he averaged more than one session per week until his death.

The question that surfaces again and again in Van Vechten’s story is whether he ever saw beyond simple self-satisfaction and opportunism. Despite the service he did to broaden the identity of the nation, was his advocacy ever about more than titillation, more than what Edward White aptly calls a “festival of self-indulgence”? He claimed, in the early 1920s, to have moved past a fetishization of all black people by having finally found one whom he hated; thus not all blacks were one-dimensional prizes. But people who knew him well saw it another way. “How can you like cities so much when you could vampire the country so much more?” Mabel Dodge asked him, encouraging him to focus his efforts on New Mexico’s indigenous peoples in the way he had on Harlem’s African Americans. Was Van Vechten ever more than a vampire?

It’s telling that the precise value of his contribution is still muddy. White tends to conceal the explosiveness of Van Vechten’s contradictions, and in doing so he makes them seem more jagged when they do appear. Though Van Vechten did his damnedest to liberate white Americans from their racial prejudices and their cultural sycophancy to European styles, he was also a personally vicious drunkard who sloshed his way through “party after party under the grip of dependency and a grim sense of duty to the myth of carefree Manhattan.” He may have been the earliest American critic (certainly the first white, thinks White) to argue for the value of blues and jazz. But the ugly side of the man — his hedonistic solipsism, his love of violent intoxication and sex tourism, qualities White dutifully prunes away from the noble arts humanitarian — cautions us from placing Carlo on the side of the angels.

The Tastemaker makes much of Van Vechten’s esprit but little of the consequences of his beliefs. This Van Vechten is curiously divorced from other white Americans invested in the same cultural struggles. Once in a while he has a moment of low spirits that seems to indicate the existence of some depth — one when he loses his mother, and another when he fears being turned away from the nightclub Small’s Paradise on account of Nigger Heaven. (He braved the door behind the ball-busting Zora Neale Hurston.) But in spite of these occasional glimpses of humanity, it is hard to avoid judging Van Vechten as a prima donna who used people for convenience, at least when his roaring libido held the leash to his personal life.

In 1941, Van Vechten opened an archive at Yale in the name of James Weldon Johnson, a black American who served as a diplomat, wrote brilliant poetry and a good novel, and was the first black secretary of the NAACP. The archive has impressive collections from twentieth-century African-American modernist literary figures, and Van Vechten ensured its strength by encouraging his friends to send him their manuscripts and literary fragments. Altogether, the materials have made it possible for the biographies of such major literary figures as Langston Hughes and Richard Wright to be written, and have undergirded much of the groundbreaking historical work that gave us a concrete sense of the Harlem Renaissance. The writer Chester Himes (for whom Van Vechten had provided a first-rate publisher; money when Himes was destitute, which was often; solid literary advice; and vodka on his birthday when everybody else forgot it) referred to the collection Van Vechten was building at Yale as “that paradise I won’t be here to see.” Through his archive, Van Vechten bent the institution into a custodian of black writers and, as a result, transformed it into a more genuine steward of American culture.

However, it turns out that Yale was supposed to be only half the story. “I am mad over the idea of breaking down segregation,” Van Vechten wrote proudly to the writer and Fisk University librarian Arna Bontemps around the time that Fisk, the intellectual leader among the black colleges, created a Van Vechten gallery in its library and accepted his donation of George Gershwin’s papers. Fisk was the designated repository of Van Vechten’s “white” materials, but it would not do for his own correspondence with such American literati as Fitzgerald and Stein. That he slated to dwell where his own crowd could reach the goodies more easily: at the New York Public Library. Yale would get a big chunk, too, plus his photographs. His famous fickleness, his insincerity, and his schemer’s dream to rank among the esteemed asserted itself in the end. A recent visit found Fisk’s collections shuttered during the summer and difficult to get to in other seasons; Edward White never even bothered to drop by. At Yale, the papers and photographs Van Vechten collected are lovingly nestled in acid-free folders on climate-controlled shelves in the glass-and-marble Beinecke Library, alongside the Gutenberg Bible and Shakespeare’s folios. The ticklish irony about Van Vechten’s archives is that he rightly adjudged the immense value of the art being produced by his black friends. Yet by welching when it came time to really put his chips on Fisk, he affirmed the logic of segregation that held sway throughout his long life.