Dwight Maxwell, a self-employed roofer and handyman, was arrested around dusk on September 7, 2012, in the parking lot of a mostly abandoned shopping center in Dunnellon, a small city in north central Florida. He had ignored a police cruiser at the side of the road ahead of him and nearly driven his black Dodge pickup into Officer Adam Robinson, who was training with the Dunnellon Police Department and involved at the time in a routine stop for a burned-out headlight. Robinson and his supervisor, Sergeant Jacob Gonzalez, pursued Maxwell for about a quarter mile down U.S. 41, the city’s main thoroughfare, before he made his way into Dunnellon Plaza.

Maxwell was asked to step out of the truck, and he complied. He is black, about six feet tall and 235 pounds, and that night he wasn’t wearing a shirt. He was told to remove his hat, and Robinson searched his work boots, because boots are a good place to hide knives and dope. In his socks and camouflage shorts, Maxwell failed a series of field sobriety tests. At one point, Gonzalez shined a light into his face and noted an absence of nose hairs, an indication that he’d snorted something irritative.

Through a window on the passenger side of the Dodge, Robinson saw a beer can behind the driver’s seat. It had been crumpled and perforated for use as a pipe but showed no signs of burns. The officers found a rock of crack cocaine near the can and two hydrocodone tablets wrapped in paper towel under a dashboard mat made of short-pile synthetic turf. The passenger seat was filled with styrofoam trays and an aluminum warming pan. It was determined that Maxwell was under the influence of alcohol or drugs or both. He was handcuffed and moved to the back of the patrol car. Members of Maxwell’s family eventually came to recover some tools in the truck’s bed. Those tools would be needed the next day, and there was no telling what might become of Maxwell. Closed-circuit video from the Marion County Jail shows him a couple of hours later, seated in a blue folding chair against a white cinder-block wall. Still shirtless, he seems to be singing quietly to himself. At one point he leans forward and says to no one, “Hell, I’ve been drunk all my life, so I ain’t worried about it.”

Maxwell was charged with two felony counts of drug possession and two misdemeanors, driving under the influence and possession of drug paraphernalia. He was arraigned on October 9 at the Marion County Courthouse in Ocala. In court that day, sitting tight-lipped next to his wife, Luevenia, he didn’t seem to notice me seated on the other side of the room and back a few rows. Another court date was scheduled, for January. I’d book a ticket from New York City. This time, my mother would ask to join me in the courtroom.

On May 30, 1982, just outside Jonesville, Maxwell lost control of his car, which spun around and crossed over into the eastbound lane of Newberry Road near County Road 241, where it collided with the car my uncle Jim was driving. My father was in the passenger seat. My brother, Frank, and my aunt Ann were riding in the back. My father died.

With the possible exception of the birth of my son, in 2011, no single event has affected me as deeply as that crash, yet nearly all I know of what actually happened that day, and the person responsible, has come in bits and pieces. My search for Maxwell himself began with the obituary of his mother, Katie Mae Bellamy, which listed all her survivors. In October 2006, I met with Maxwell’s sister Sylvia, who told me what little she could about the afternoon in 1982 when her brother killed my father. She had seen Maxwell that day at a family cookout, she recalled, before he left for a job. “Next thing we knew, we get a phone call, said that he had an accident.” Sylvia also told me that a nephew of theirs had been arrested the previous Thanksgiving after a hit-and-run involving a teenage boy in DeLand, on Florida’s mideast coast. I began to travel to attend the hearings. Over the next six months, I met several of Maxwell’s other siblings and maintained the hope that he might make an appearance himself. He never did.

On these visits, I would stay with family in either Gainesville or suburban Orlando, both of which make tiny Dunnellon and even Ocala, the Marion County seat, feel like remote outposts. One afternoon, my aunt Ann took me on a drive to look for the crash site. We went west, toward Jonesville, on Newberry Road, and after a while turned around and headed back east, but she couldn’t be sure anymore. A letter I have from her contains my father’s last words: “Hold on, we are about to be hit.”

My father’s postmortem examination, prepared by the Gainesville Medical Examiner, arrived in September 2007. It says that he “died with or shortly after impact at 4:05 p.m.” Attached to the handwritten report is a diagram indicating every laceration and fracture. His head sustained just a small cut above the right eye. His neck and spinal cord were fine, but both his ankles were shattered when he tried to brace himself. Almost every rib was cracked, and jagged bone sliced him inside. The cavity around his lungs filled with blood. There were glass fragments in his chest. His right shoulder had smashed through its girdle. He was wearing a University of Florida T-shirt and a pair of white swim trunks with red and blue stripes. No shoes. No socks. He had been out in a boat near the mouth of the Steinhatchee River in the hours before the crash, lounging in the sun.

For much of my life I’d hoped Dwight Maxwell had rotted in prison. That feeling, and the often racist thoughts that went along with it, only began to change in early 2005, when I first read his mother’s obituary, began to meet his family, and came across the records of his arrest and sentencing. In a letter sketched out over two pages of a legal pad and mailed to the judge in his case, Maxwell provided some information about himself “for the purpose of mitigation.”

FACTS:

1. I don’t rob or steal. I’m a solid citizen.

2. I fear God. I’m deeply sorry I cause some one Death.

3. I would gladly spend this time trying to rectify this error. By work x # amont of hr’s per mo. In the com. for charity & spend x # weekends in jail. And pay as much restitutions as possible.

4. There is no other income in my house hold to support my wife and son a few cow’s and a very small farm with a mortgage payments of $209.63 plus household expense.

5. My wife and I belong to A-O-H Holiness Church of Christ. And both of us have been mortified by this mans Death. I am so sorry.

6. I intend to seek all the help I can get so I will never drink again. I realize now the price, and it’s to great.

7. I have accepted Jesus Christ as my personal savior and I have been change.

8. The information I give here is true so help me God.

He was twenty-six. He was a person. And once I’d seen what he had to say for himself — that he lived with his wife and son and very little else, that he knew his mortgage to the penny — I began to suspect that I was the monster for hating him. I began to wish that he’d never been sentenced at all. Too many lives had already been ruined. With what vestiges of sacramental Catholicism remain in me, I wanted us to be reconciled. Although I have given up eternal life as an idea — closure for both the saved and the damned — I still try to salvage what I can of my tradition and its promise of redemption. Without hope for another world, Christianity has become for me about forgiveness in this one. When I finally built up the nerve, in January 2008, to travel to Dunnellon and face Maxwell for the first time, I had this in mind. I went because I thought we needed each other; I thought we could help each other out.

U.S. 41 connects Miami to Michigan’s Upper Peninsula, running through Dunnellon north into Newberry, ten miles from where my father was killed, and then six states later passing within fifteen miles of the home in Waterford, Wisconsin, where he’d been teaching me to read. Maxwell’s house is across some railroad tracks, just off the highway, eleven long and rural miles north of downtown Dunnellon. It was cold the day I arrived. Orange growers were spraying their groves with water so that the ice would insulate the fruit.

I knew I was at the right place when I discovered a tattered and rained-on piece of poster board at the front gate:

“it’s our anniversary”

“30” years

dwight @ luevenia

When Maxwell realized someone had come to see him, he stepped out from behind the fence surrounding his property. He wore a black ny knit cap, jeans, old black sneakers, and a blue denim shirt under a lighter-blue sweatshirt, which was inside out and dirty. He hadn’t been expecting me, but he’d heard, from family, that I wanted to meet him. He suspected at first that since I’d spent so much time trying to find him — three years now — I might be there to kill him. That’s what he said, although he didn’t seem worried. Had he been afraid of me that afternoon, he said, he would have turned and run as soon as he realized who I was. He’d realized fairly quickly. When we shook hands, tears formed in his eyes but did not fall.

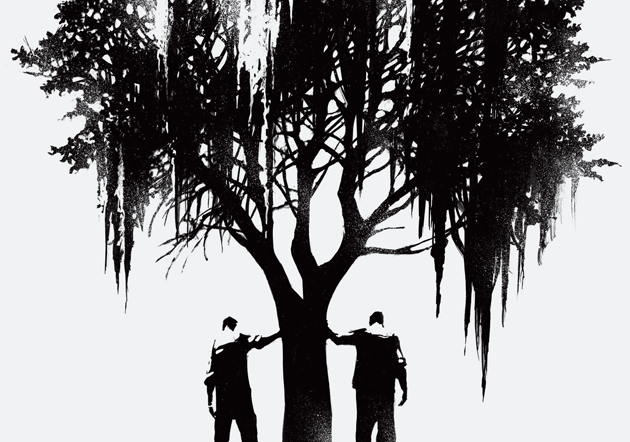

Maxwell spoke softly. Sometimes what came out was a mumble. After a while, seeing I’d caught a chill in the shade of a giant tree, he led me into the sun. I’d left an old brown sweater in the car and had been standing with my arms crossed for twenty minutes. I was grateful; the sun felt good. We began to talk about forgiveness and God.

“If I want to end up with God when I am placed in the ground,” Maxwell said, “I have to stay on the right path.” As if to show the way — the straight path — he pointed across the stretch of land behind his brother Robert’s trailer, property he’d grown up on. It was all right here: family, security, maybe even goodness. For Maxwell as a child, his was a neighborhood where, he remembered, “my mama beat you and your mama beat me.” Back, he said, when kids walked around in their Fruit of the Looms, back before kids ever left this place. (On his mother’s side, beginning with his grandparents, Maxwell’s family first appears in the Marion County census in 1930, in a part of Dunnellon called Romeo.) Maxwell’s sisters and most of his brothers left and raised nephews and nieces on other land, and some of the nephews, I knew, had gotten into trouble. Wendall was the one arrested in DeLand. Gerald was shot dead in 1992, as a high school senior, in the parking lot of Rainbow Square, another shopping center on U.S. 41.

Maxwell had been released in 1985, after a hard year and a half, which was followed, he assured me, by years of nightmares. I let him know I’d turned out okay, that my mother had remarried, and that I was here in good faith. But we made little progress beyond that. He had gestured me out of the cold and I had clasped his hand, but we could find no way out of what James Baldwin might have called our “common trouble.” I was too city, he said. He was backwoods. Low-down. Wasn’t fancy. I was white. He was black. He’d killed my dad. Although he made it clear from the start that he was deeply sorry for that fact, he eventually sent me away, insisting that he had to get back to his work. He agreed to meet again the next evening and to bring Luevenia, then ducked away.

The following morning, Maxwell called and left a message. He was very clear and did not mumble. He even said the important things twice. “Hey, Scott. This is Dwight Maxwell. I talked with you yesterday. I talked with my attorney, and he advised me not to talk to you about anything. I’m sorry, but I talked to my attorney, and with my adviser, and he talked to me and he told me not to talk to you about anything. I’m sorry I can’t help you. Bye.”

On January 25, 2013, my mother and I arrived in Judge Brian Lambert’s courtroom before Maxwell did. Her interest in him had grown alongside mine over the years, and so, to a certain degree, had her sympathy. Decorum in Lambert’s courtroom, announced a bailiff, involved not making eye contact with the judge. A woman seated in the row in front of us clipped her fingernails.

Maxwell arrived alone, five minutes after the session began, and found a seat in the front row on the opposite side of the room. He wore camouflage cargo pants and a gray sweatshirt. Luevenia came later and sat next to him to wait. She cleared her eyes with her fingers. For nearly an hour — with case after case appearing before Lambert, most handled in minutes — Maxwell waited his turn, either leaning back with his arms crossed or bouncing his knees with his head down and his hands in his lap.

Most of the defendants that morning did what most defendants do. They pleaded guilty or no contest; they were processed and led out of the courtroom. When one defendant hesitated, his mother, in the gallery, shouted out, “Take the plea!” He did. With each case, Lambert, who is considered no-nonsense, fair, and efficient by both the state’s attorney and the public defender, wished the defendant good luck.

This is the way that criminal justice usually works now. “Almost no one ever goes to trial,” writes the Ohio State law professor Michelle Alexander in her influential 2010 book, The New Jim Crow.

When prosecutors offer “only” three years in prison when the penalties defendants could receive if they took their case to trial would be five, ten, or twenty years — or life imprisonment — only extremely courageous (or foolish) defendants turn the offer down.

Maxwell had taken a deal in 1982, pleading no contest to vehicular homicide when the state offered to drop three additional felony charges. Since then, plea deals have only become more common, with the portion of felony convictions that result from trials declining from one in twelve during the 1970s to fewer than one in forty today.

Maxwell was eventually called. Explaining that at trial the state would seek a five-year sentence, the prosecutor offered Maxwell a deal that included 270 days in jail and two years’ probation. Maxwell then did the unthinkable: he turned down the offer. His trial, it was decided, would begin in a month. Everything transpired very quickly. My mother turned to me and said, “What just happened?” I had no answer. My best guess was that he was trying not to make the same mistake twice — not with a guarantee of at least one more month of freedom ahead of him. Incarceration was just that bad.

A few weeks later, as I was waiting for the trial to begin, I learned that the state had accepted a counteroffer from Maxwell’s public defender. Someone had evidently persuaded Maxwell his chances at trial were poor, and he had changed his mind. Now he pleaded no contest on all four charges. His sentence was four years of drug-offender probation, including random drug screening and the requirement that he avoid alcohol entirely — drinking it, possessing it, entering bars or liquor stores. It seemed like a longer but lighter sentence. He had avoided prison time, at least in theory.

In practice, the truth was more complicated, as I would learn from Assistant State Attorney Bill Gladson, whose office had prosecuted Maxwell’s case. Gladson took an interest in my story, in part because he had no record of my father’s case in his files. Sitting across from me at his desk, puzzling over how he could have overlooked it, Gladson ran a hand down his face in a way that brought to mind a particular high school football coach from television — disappointed in his team, sure, but even more disappointed in himself. Finally, when I showed him my old Gainesville Sun clippings, he realized that the crash had been in Alachua County, not Marion County. Files like these don’t travel.

Gladson explained the logic of the deal as the state saw it. Florida sentencing guidelines are based on a score sheet that categorizes felonies into ten levels according to their severity. A primary felony offense earns anywhere from 4 points (level 1) to 116 points (level 10). In Maxwell’s case, the possession of cocaine, level 3, amounts to 16 sentencing points; he accrued an additional 2.4 points for the hydrocodone, and 0.2 points each for the misdemeanors of driving under the influence and possession of paraphernalia, for a total of 18.8 points. Since July 1, 2009, as part of Florida’s money-saving prison-diversion program, unless a convict scores more than 22 points, he is typically given a “nonstate prison sanction” — in other words, a maximum sentence of a year in county jail.

The state’s offer of 270 days signaled to the defense that they didn’t want to go to trial. They would have been happy with a counteroffer of 120 to 180 days with three years’ probation. What the state got instead Bill Gladson had jotted down on a legal pad the day before we met:

Double probation

Drop jail

Over 22

Now if he VOPs he goes to prison

Gladson translated. The state “accepted a counteroffer with an extended drug-offender probation in exchange for the two hundred seventy days in jail, with the understanding that if he violated his drug-offender probation his scores would allow him to go to prison with the additional six points. This factored in the reality that drug-offender probation is difficult for people to complete.”

In other words, with four years of drug testing almost sure to catch him up, Maxwell, who was not eligible for prison after his arrest in September, is probably going to end up there sometime in the near future. Not necessarily, but probably. “Considering in this case that he’s charged with cocaine and DUI, and knowing that the prior vehicular homicide involved alcohol,” Gladson said, “it surprises me that there have been no other offenses in the past thirty-one years.” For Maxwell to be able to meet the terms of his probation would be not only surprising but — it struck me, in talking with Gladson — a little disappointing too, as far as the state was concerned.

With just 2 percent of criminal cases in Florida going to trial, finding ways to game the score sheets seems to have become the prosecutors’ primary occupation. The state took the deal because it made the more severe punishment more likely.

I met next with the chief assistant public defender, Bill Miller, in a small and windowless office crowded with memorabilia of his hero, Roberto Clemente, and a collection of nature photos Miller had taken himself. I explained my relationship to the case and asked him about what the state sees as a very likely outcome — Maxwell in prison as a result of the deal that Miller’s office negotiated.

Miller said he was sure that Maxwell’s attorney had “made him aware of all the consequences of a plea and what the statutory maximums are, and would have told him, ‘You are exposed to that.’ ” “That” being ten years’ incarceration.

“In your opinion,” I asked Miller, “based on what might have been two hundred and seventy days in jail and two years’ probation, do you believe this is a better outcome for the client?”

“Depends on what he does with it,” Miller said.

I nodded in a way that felt conspiratorial.

“I will say this,” he concluded. “I would like to go back to the days when we actually considered rehabilitation as a goal that was admirable.” He was referring to Florida Statute 921.002 (1)(b), which became law on October 1, 1998: “The primary purpose of sentencing is to punish the offender. Rehabilitation is a desired goal of the criminal justice system but is subordinate to the goal of punishment.”

I returned to Maxwell’s house that May. The property was just as I remembered it, except now there was a dog. A black Dodge sat under a shelter away from the house. The trailer on the other side of the property and beyond the fence, I knew, belonged to his brother Robert, who lived with his wife, Rhonda. I found no one at either home, but just as I was leaving, Robert drove in and parked a giant red pickup under the shelter on his side of the fence. I introduced myself.

Robert chewed on a cigar but did not light it. He had little to say, but he led me under a tree, out of the heat. In fields beyond the trailer and an outbuilding, on land that had belonged to his grandfather, Robert grew cantaloupes and watermelons that he sold wholesale at a farmers’ market to the proprietors of local produce stands. He also did landscaping. I’d grown used to finding this catch-as-catch-can industriousness around Dunnellon, where unemployment is around 18 percent. I gave him my phone number and asked him to pass it on, and he suggested I try Maxwell’s brother-in-law, Archie Jeffries, at his house close to the center of Dunnellon.

I found Jeffries sitting on a small cooler, applying wax to his truck’s front end. I made another introduction and asked whether he knew that Maxwell had been arrested in September. Jeffries told me he hadn’t heard anything at all: “He stay to himself.” Maxwell’s sister Regina, standing in the back doorway to their house, not venturing out, also hadn’t heard of the arrest. “He’s been saved before,” she said. “He grew up in holiness. He know who to look up to. He know the Lord.” She didn’t seem too sure about me, though: “It’s so hard to trust anybody. Trust God.” It’s right there in the Bible: “Put your trust in no man,” she advised. It was an allusion to Psalm 146. When I asked whether they knew who might have appeared on the scene to gather the tools from the roofing job, they said it was probably Maxwell’s brother John, who lived in a neighborhood called Chatmire.

I first heard about Chatmire from Officer Robinson, who had spotted me one morning just as I had begun to walk the quarter mile along the highway between where he was nearly clipped by Maxwell and where Maxwell was arrested. Turning in to a KFC, he lowered the passenger-side window of his cruiser, and we talked for a while near the entrance to the drive-through. He seemed genuinely interested in my well-being and advised me against heading into Chatmire, which he described as a high-crime area. Drugs mainly. He brought up a local map on his computer and showed me the neighborhood’s boundaries. The danger zone, as he saw it, began just around a bend from the shopping plaza where Maxwell pulled over that night.

Without an address, finding John’s place was a matter of asking the first person I met in Chatmire, a middle-aged man looking after two young girls. He walked me back to the road and pointed out where I would have to make a turn, then another, where I’d go from pavement to dirt. The house would be brown, and there’d be a white truck. The man then loaded the girls into his car and led the way, sending me down the dirt road with a wave of his arm before driving off. Finding things just as they’d been described, I rapped on John’s screen door, and he came out wearing a white T-shirt, leading with his belly.

John showed me through the yard, past a shadeless floor lamp and the box from a flatscreen television, to a table under the carport, where he offered me a seat. He had driven by that evening, he told me, and, seeing the police lights in Dunnellon Plaza, gone to investigate. He’d recognized his brother’s Dodge. Robinson and Gonzalez, John told me, had a “bad case of ass” that night. Still, the officers allowed the family to collect the tools. “A lot of what goes on,” John said, “has to do with how they think about black people.”

As I drove away, past the home of the man who’d directed me to John’s house, back toward Dunnellon Plaza, a car behind me raced up close, honking. Startled, I pulled to the side of the road and watched as two girls leaving Chatmire smiled and waved.

Between meetings with lawyers and cops, for most of a week I’d driven back and forth along U.S. 41 hoping to find Maxwell at home. So the morning of my last day in Dunnellon, I took a different approach into the neighborhood, a road a little farther up U.S. 41, where the turnoff is marked with a sign fastened to a tree that advertises Robert’s business, maxwell logging, buying & cutting timber & land clearing. When I arrived at the house, I paced the fence, peering in where I could to spot movement back behind the collapsing garage, thinking I might see some sign of life in the house through the raising of a window shade. But there were only roosters in the distance and crickets. The dog lay still behind the fence. I returned to the side of the car and waited.

A young woman approached from the north, riding a horse, which got the dog’s attention. The woman was in a University of Florida tank top and wore her hair in a ponytail. She lived nearby but couldn’t tell me much about Maxwell beyond his reputation for making excellent ribs, which he sold at a place called the Log Cabin Store, a few miles down Highway 328. He sometimes had a smoker, on wheels, in the yard. This explained the warming pans and styrofoam trays I’d seen in police photos from the night of his arrest.

Along the highway I found the Log Cabin Store and the smoker, emblazoned in red with the word rib. No one was cooking. The woman behind the counter apologized; the man who sold the ribs — Max, she called him — was around only on the weekends. I headed back to Max’s house, where I found the dog calm again and the roosters and crickets still at it. I lasted maybe another twenty minutes in the heat before deciding to head back into town for lunch. I drove away.

And there he was. Wearing the same sort of floppy hat and camouflage shorts he’d been arrested in, Maxwell was riding a bicycle north along U.S. 41. The road had a slight grade, which I hadn’t noticed before, and he was pedaling hard. We made eye contact, and I may have smiled before he crossed the highway in my rearview mirror. In the time it took me to wheel the car around, he’d vanished.

I set out again in the direction of the Log Cabin Store, keeping an eye on my rearview mirror. After about a quarter mile I turned back, and once again on U.S. 41 I spotted another direction he might have gone. I took NW 13th Street, about a half mile to the west and around a bend past Pine Island Prairie. He hadn’t come this way either. When I returned to 41, however, out of nowhere, there was Maxwell, pumping his bike toward home. I turned the car around on Highway 328, bottoming it out in a driveway that didn’t quite meet the road, and parked near a stop sign.

That Maxwell had disappeared again seemed impossible. I began to walk along the highway toward where I’d last seen him. A stream of cars and trucks went by. A minute or so down the road, I spotted a blue Schwinn at the edge of the narrow woods between the roadway and the railroad tracks, which run parallel through this part of Marion County. I heard rustling.

“Dwight,” I called, stepping into the undergrowth. “Dwight!”

Maxwell emerged from behind a tree. “You remember what I said to you?” he shouted. He was tugging a magnolia sapling from the ground. He moved forward with it, and I stepped back. He then started pacing, tugging up branches and dragging them along as he went. I asked what he was doing; the magnolias, he said, were for his yard.

I asked whether he would come out to talk. I had to raise my voice for him to hear me over his stomping and the traffic. It’s a terrible thing, I said, to have one thing happen to you that changes your whole life like this. The accident is something we shared, I told him, something I’ve been living with my whole life. I shouted, “Maybe there’s something good that I’m trying to do here!”

He said he couldn’t understand at all what I was trying to do.

“Tell me what happened in September.” I told Maxwell I knew what the police had to say. “But what about you?” I was going to write this all down. “If that’s not the true story, then it’s up to you to tell me the true story. Maybe things didn’t go right for you. And maybe they could have gone better. And maybe there’s a story to tell about that.”

He told me to write whatever I wanted. He didn’t care. He wasn’t going to say more than he’d already said.

Maxwell had moved to the tree line and was attempting to pile the branches on the grassy shoulder of the road, near his bike. I offered to move a branch out of his way, and he told me to stop. I insisted and then struggled. It was getting hot in the woods. I asked whether I could help him carry the branches. I asked whether we could go to his house and talk.

I know how difficult it must be to get back on your feet, I told him.

He agreed; it was.

It had been a long time for there to be no other trouble, those thirty-plus years. Again, he agreed.

“If you violate your probation,” I told him, “you’ll go to prison.”

He said he knew.

“Do you think it’ll be difficult?”

“It’s been difficult my whole life.”

Out of the woods, Maxwell climbed back on his bike and began pedaling, dragging the magnolia branches behind. I asked again whether I could follow him home and talk more about this. He continued, shaking his head and silently repeating no. He pedaled on, not so fast, but fast enough to increase the distance between us. I was not going to run.

Once he hit the railroad tracks after turning from U.S. 41 onto Highway 328, Maxwell got off the bike and walked, now about fifty feet ahead of me, still dragging the branches. He walked along the tracks leading to his house. I stopped and let him go.

Eventually, he climbed back on the bike and pedaled again. He was at such a distance and was pedaling so slowly, obscured too by the shade cast over the tracks, that it was difficult to tell which direction he was going. I turned around to walk away, and then faced his shape again. For a moment, I thought he was coming back.