We start in darkness. After fighting our way through the dingy, low-ceilinged, crowded waiting room that serves as New York City’s current Pennsylvania Station, we pull out through a graffitied tunnel that follows one of the oldest roadbeds in America. Freight trains once clattered along open tracks here, spewing smoke within a few dozen yards of the mansions along Riverside Drive and attracting one of the most dangerous hobo encampments in the country, before it was finally all buried beneath a graceful park in the 1930s. Today, we emerge into sunlight for the first time in Harlem, following a route up the glorious Hudson River, past Bear and Storm King Mountains, and the old ruined Bannerman castle on Pollepel Island.

A dining car is attached at Albany — a delay that takes an hour. For that matter, we are not actually in Albany but in Rensselaer, across the river, where in 2002 Amtrak completed the largest train station built in this country since 1939 — a structure that has all the individuality of a shopping-mall Barnes & Noble. But we gladly seize the opportunity to stand on the open platform and stare across the Hudson at the capital. It’s a splendid early-fall evening, and we’re at the start of an adventure. We smoke and stretch our legs, and I chat with Derrick, our sleeping-car porter, who is in charge of providing for all the passengers in his five compartments and ten “roomettes.” He tells me he emigrated from Uganda and has been working for the railroad for the past two and a half years.

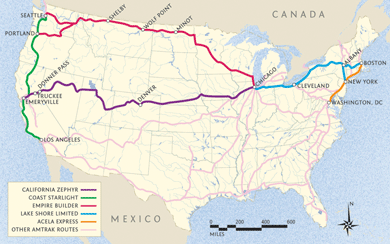

Empty café car near Tomah, Wisconsin, on the California Zephyr from Emeryville to Chicago. Unless otherwise noted, photographs by McNair Evans from In Search of Great Men, an ongoing project documenting long-distance travel on Amtrak.

Amtrak’s long-distance dining and sleeper-car crews tend to be efficient and almost indefatigably friendly, despite the long trips and the relentless demands of their jobs. A high percentage of them are people of color, an old railroad tradition. (George Pullman, searching for an uncomplaining workforce to service his new cars, began the practice of recruiting former slaves to work as porters soon after the Civil War. Yet they did not prove as pliable as Pullman would have liked; though it took them decades, they organized their own union, the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters, under slogans such as “Fight or Be Slaves,” and hired a socialist firebrand named A. Philip Randolph to run it.)

By the time we step back on the train in Rensselaer, we can hear the dining-car crew setting up for the evening meal. Once, railroad-dining-car chefs produced some of the best food in America at almost any time of the day or night, serving up regional specialties on real china, with glass, silver, and fine linen napkins. Today the food is prepackaged and warmed up, airline-style meals served mostly on hardened paper or plastic dishes. All across America the menus are the same: a choice of reasonably edible steak, hamburger, chicken, salmon, or pasta, accompanied by a couple of dinner rolls and an anemic salad. But the real attraction is the strangers you’re seated with.

My first night I sit with a merry retired couple, Mark and Linda, a former middle-school teacher and an accountant from Hyde Park, New York, who love train travel. They constitute, I will discover, one of the three leading categories of long-distance train passengers: train enthusiasts, derisively called foamers by Amtrak crew members. (The others are tourists from Britain and those who, for one reason or another — physical or psychological — cannot tolerate the many inconveniences of air travel.)

Mark and Linda are foamers. They buy everything on their Amtrak credit cards in order to run up rewards points, as do many of the enthusiasts I encountered. Mark is also a model-train buff. They are New Deal liberals, and though outright politics is almost religiously avoided around the close quarters of an Amtrak dining table, most sleeping-car passengers will let on quietly, almost conspiratorially, that they believe in things like public investment, and not just for trains.

Mark can reel off the names of the towns we are passing in upstate New York even in the darkness — “Amsterdam, Utica, Syracuse!” — from his time spent camping in the area with his two sons. But he and Linda are disheartened by the economic disaster that has hit much of upstate, and wonder what is to become of the region where they’ve spent so much of their lives.

We are following the route of the New York Central’s most famous train, the 20th Century Limited, which once rivaled Europe’s Orient Express in extravagance. At five o’clock every evening, porters used to roll a red carpet to the train across the platform of Grand Central Terminal’s Track 34. The women passengers were given bouquets of flowers and bottles of perfume; the men, carnations for their buttonholes. The train had its own barbershop, post office, manicurists and masseuses, secretaries, typists, and stenographers. In 1938, its beautiful blue-gray-and-aluminum-edged cars and its “streamline” locomotives — finned, bullet-nosed, Art Deco masterpieces of fluted steel — took just sixteen hours to reach Chicago, faster than any train running today.

The 20th Century Limited became a cultural icon. It was a luxury train, but middle-class people rode it, too. In the heyday of American train travel after World War II, they also rode the Broadway Limited, the Super Chief from Chicago to Los Angeles, and the California Zephyr, which were nearly as celebrated and beloved.

Some twenty years later, it was all over. Virtually every privately owned passenger-rail line had died by 1970, done in by cheap gas and jet engines. The pathetic mishmash of decaying stock that remained was lumped together into a Nixonian experiment: a publicly funded, for-profit corporation dubbed Amtrak. It was widely believed that this arrangement was set up to fail, because saving trains seemed pointless. Americans wishing to travel long distances could drive their cars on the interstates or take a plane or intercity bus. Railroads seemed as archaic a mode of transportation as the wagon train.

But unexpectedly, ridership began to creep up — from fewer than 16 million in 1972 to more than 21 million in 1980. After 9/11, when air travel turned into unmitigated misery, it shot up to 30 million. Along the Northeast Corridor, between Washington and Boston, which generates 80 percent of Amtrak’s revenue, the train’s share of all combined plane and rail traffic has more than doubled, from 37 percent in 2000 to 75 percent today.

Barack Obama, during his 2011 State of the Union address, promised to lead America into a green industrial economy, and he committed his administration to a vision of giving “eighty percent of Americans access to high-speed rail within twenty-five years.” In 2009, invoking our history — Lincoln starting the transcontinental railroad while the Civil War raged, Eisenhower building the interstates during the Cold War — and challenging our national honor (“There’s no reason why we can’t do this: this is America”), the president made the argument that “building a new system of high-speed rail in America will be faster, cheaper, and easier than building more freeways or adding to an already overburdened aviation system — and everybody stands to benefit.”

Trains would help end our dependence on oil as well as our rapid transformation of the earth’s climate and allow us to re-create sustainable communities. Now we would have new trains, fast trains, magnetic-levitation trains that never touch the ground. Not just between nearby cities but across entire states and regions, eliminating the need for new airports and highways, replacing countless barrels of oil with electricity, or maybe using no traditional power source at all!

Yet by the fall of 2013, plans for any new high-speed national rail system — plans even for seriously upgrading our existing rail system — had been delayed for the foreseeable future. How had this come to pass? We used to value trains, used to imbue them and their stations with all the grace, beauty, and efficiency we were capable of as a people and a democracy.

To cross the continent by train in the fall of 2013, just as the organized right was about to shut down the national government, was an opportunity to trace our country’s entire fantastical boom-and-bust progress. It was also a chance to glimpse an American treasure that if squandered might never be regained.

The Lake Shore Limited is not, strictly speaking, a limited train, since it makes eighteen stops on its way to Chicago. The name is due mostly to Amtrak’s effort to evoke the great trains of the past, but it does follow the old water-level route around the Great Lakes, advertised as superior for sleeping because it does not climb and descend the mountain grades of the Alleghenies.

Nonetheless, I’m awakened repeatedly by the banging of cars and the grinding and wrenching of metal wheels along the track. The Lake Shore Limited pulls into stations or onto sidings to let other trains pass, then sprints to make up the time — a constant slowing and accelerating that is characteristic of long-distance Amtrak trains and that makes sustained sleep difficult.

As rains slow construction work in California, a man travels from Sacramento to Iowa on the California Zephyr to spend the winter building grain bins.

At half past three in the morning we stop again, and I peer outside into the darkness. There is only a flat little box of a train station visible, and a small parking lot surrounded by a chain-link fence. A few figures hurry furtively to their cars. I watch as they drive out past a single, towering wind turbine, a tangle of utility wires, and a looming football arena with a sign proclaiming it FirstEnergy Stadium. Only by looking at the Lake Shore’s timetable can I tell that we are in Cleveland.

“FirstEnergy” is appropriate enough. Cleveland was the hub of America’s first real energy boom, in the original oil fields of western Pennsylvania and eastern Ohio. This is where John D. Rockefeller made his fortune, not so much because of any expertise he had in finding or refining oil but because of a deal he cut with the railroads whereby they agreed to charge all his competitors as much as double the rate while providing Rockefeller with a secret discount and kickbacks on his competitors’ shipments.

The landscape before me today, a hundred years later, tells a different story of corporate hegemony. The old Cleveland station, where intercity trains stopped until 1977, was an outstanding example of Beaux Arts design constructed in the late 1920s by local brothers named Van Sweringen in imitation of New York’s Grand Central.

The station is still gorgeous, but trains don’t run there anymore, save for a few local commuter lines. Amtrak couldn’t afford the rent, so instead it lets anyone who wants to go to Cleveland off where we are, at Lakefront Station. Lakefront is what foamers call an Amshack — a building that looks as if it might be a storage facility for the files of an accounting firm that went out of business sometime during the Ford Administration.

It used to be that private corporations could be relied on to build exquisite public spaces at their own expense, not just slap their names on a finished product. American train stations were once the most magnificent in the world. Even in the smallest towns, they tended to be little jewels of craftsmanship. In bigger cities, they were the first monumental modern buildings erected without reference to God or king, built by the people to move the people.

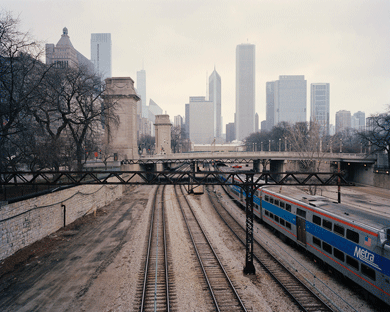

Metra tracks to downtown Chicago near the transfer point between the California Zephyr and the Lake Shore Limited.

Most of the leading American architects from the 1890s through the next forty years tried their hand at a train station, or more than one — Daniel Burnham, Cass Gilbert, Charles Follen McKim, Henry Hobson Richardson, Stanford White. What they produced were predominantly Beaux Arts beauties but also pretty much the entire array of architecture practiced in this country up through the 1930s, including some astonishing amalgams of styles.

Many of the great stations have been ingeniously repurposed and restored as commuter-train stops, shopping malls, museums, restaurants, even movie theaters, thanks to the foamers and the more enlightened city governments stuck with them once the old railroads died. Yet the removal of function from form is an essential societal disconnect. As Ed Breslin and Hugh Van Dusen write in the lavishly illustrated America’s Great Railroad Stations:

Each station functioned as did the main gate on a medieval town: it was the welcoming portal to that community, and it was meant to impress, comfort, and reassure the visitor. Each station was a focal point of collective pride, a civic monument large or small. All embodied America’s love of, and genius for, commercial excellence. Whether built on the scale of a small chapel, a substantial church, or a monumental cathedral, all of these stations personified and reflected America’s secular spirituality fueled by the belief that life could endlessly be enhanced by aesthetic beauty, industrial might, technological know-how, and creature comforts while traveling in style with alacrity from one point on the compass to another.

In Chicago’s Union Station, the Metropolitan Lounge is in chaos. The station is one of Daniel Burnham’s surviving gems, but for some reason its grand hall lies empty and still, while long-distance passengers and their luggage are jammed into a drab, undersize basement room. Only Amtrak could turn a luxury lounge into a refugee center. Most of the passengers struggle and sway hauling their baggage down to the train, then up the twisting stairs inside the double-decker cars.

Gazing out the window in the dappled afternoon light a few minutes before we leave, I see luggage handlers piling bags atop an ancient, wood-bedded open wagon. I might have witnessed much this same scene, even this same equipment, at Lincoln’s first convention, back in 1860, the first in a long line of political conventions of all denominations — Democratic, Republican, Bull Moose, Socialist, Communist — held in Chicago, because it was the nation’s premier train hub.

Over on the next platform are a couple of antique railcars, a charter doubtless ordered up by some of the wealthier foamers. There are entire associations of private railroad-car owners and renters who still hook up their cars to Amtrak trains. This is a subtler threat to the future of Amtrak and passenger-rail service than are the budget-cutters in Congress — the danger that train travel will be seen as merely a hobbyist’s preoccupation. But it’s impossible to deny the beauty of the antique observation car I can see from my window: it’s another perfect artifact from the height of train design, full of padded leather armchairs and matching Art Deco side tables.

In the 1930s, America was mad for design, especially when it came to machines. Devastated by the Depression, facing their first serious competition from airlines and automobiles, the major railroads completely overhauled their rolling stock. Many trains were converted from steam to cheaper diesel-electric power. All were put in wind tunnels, tested to see what could make them go faster, use less fuel, take turns more quickly and more safely. The most prominent industrial designers in the country went to work on them. They streamlined trains, lowered their center of gravity, cut their weight, and increased their speeds. The designs alone made the trains seem fast.?Amtrak’s observation cars today are built with no equivalent sense of artistry — or any artistry at all — but they are comfortable, maybe the most agreeable means of travel aside from ocean-liner staterooms. One sits up high in the double decker, at a table or a long row of swivel chairs that run down each side. There are tables and drinks stands at each seat, and the windows provide an almost 360-degree vista as you move through the American countryside. There are no observation cars east of Chicago because of low-hanging wires, but in any case the double deckers are best served by the West, where you are viscerally reminded of just how vast our country is, how abundant and majestic — where the words of all the old patriotic songs come true.

Traveling through Wisconsin, we spend the rest of that day passing fields of perfect rows of cabbages, pumpkins, beans. By the following morning, we are in North Dakota, and the landscape becomes sparser and more monotonous: miles of shallow marshes and fields of high green grass, occasional rows of old trees planted eighty years ago by the youths of the Civilian Conservation Corps to serve as wind breaks. But all of it is punctuated by breathtaking beauty. A pair of eagles swoop and glide low over a golden field of wheat near Williston. A white horse ambles and grazes its way alone through some marshland. A flock of small black birds rise and wheel suddenly through yellowed grassland. Black cattle stand out against a pasture, muzzles up, watching us pass.

The company in the dining and observation cars is so amiable that I was dissuaded from asking people’s last names when they weren’t offered. The passengers talk quietly and freely with one another. A pair of children march in with their mother, pretending to be a parade. A young man with an enormous Afro sits alone reading. A group of blustery young white men come in, regaling one another with tales of getting arrested.

At my table at lunch there is Kate, an English assistant headmistress, just retired. She tells me about how she taught in New Guinea with her husband for seven years, then raised four children by herself after being widowed very young. Now she is finally on holiday, having sent the last child off to university. Kate is fascinated by America’s sheer size, and also by its countless religions: “I think they’re related. When people want to, they simply go off and start another one.”

The train makes her case for her. In a single afternoon moving through North Dakota, I have conversations with an Amish person and a Mennonite. There are plenty of each traveling on the Empire Builder. Alice, the Mennonite, is a pretty, birdlike woman who owns her own catering business in Canada. Apart from her old-fashioned dress and her hair bun she seems thoroughly modern, showing me a picture on her phone of her congregation’s little blue church.

Felty Miller is a young construction worker, part of a large party of Amish bound from western Tennessee to a wedding in Washington State. He does not object to my interrupting his reading of a big illustrated Bible in the observation car. Like the other Amish men, he is dressed in a neat dark-blue shirt, pressed black pants, and a vest, and has light-brown, curling chin whiskers. He dandles Elias, his two-year-old, towheaded son, over his knee as he patiently explains to me that, yes, he is used to the speed of the train, having ridden in trucks that the outside contractors the Amish work with drive. He speaks of how bad the economy still is — and offers the opinion that more money needs to be put into the national rail system.

For all the pastoral beauty of the Plains states, passenger trains are interlopers here amid the hidden industrial life of the country — hidden, at least, to those of us who live in more crowded places. In Wolf Point, Montana, we watch as a truck heaped with rolls of hay drives by on the cracked two-lane highway. We pass huge grain silos, some abandoned and open to the elements, most still in use, a few houses and barns huddled nearby. Interminable freight trains sweep past us.

Some of the freight trains are made up of boxcars, some of the oil-tank cars now overwhelming our neglected infrastructure in a series of spectacular derailments and fires around the country. On one freight train alone, I counted 104 tank cars, fat and rounded as big black pigs. They slow to pass us, but still we rock in their wake like a small boat on a heavy sea.

Freight is the main economic reason why trains — or any other form of mass transportation — exist. “A passenger train is like a male teat — neither useful nor ornamental,” groused James J. Hill, whose nickname, “the Empire Builder,” adorns our train, when he was running the Great Northern Railway through these parts more than a century ago.

U.S. passenger trains may be, “quite simply, a global laughingstock,” as Time magazine put it a few years ago, but American freight trains “are universally recognised in the industry as the best in the world,” according to The Economist, and they still have an estimated 43 percent share of the freight market in the United States — the highest proportion in any industrialized country, and nearly ten times the total tonnage moved by freight trains in the entire European Union.

Freight companies also own most of the rails in the United States, which is one reason why U.S. passenger trains lag so far behind high-speed systems in Europe and China, where trains rocket along at more than 150 miles per hour, much less Japan’s new Shinkansen bullet, which runs at 200 miles per hour. All these trains travel on dedicated tracks or in sunken, walled corridors, and so can be built light and fast.

Amtrak trains, by contrast, must weigh about twice as much as the average European passenger train in order to have any chance of surviving a potential collision on the rails they share with the freights. Even the Acela — the result of Amtrak’s big 1990s effort to build a train that might average 150 miles per hour on the Northeast Corridor — is so bulky and plodding that the French and Canadian engineers working on it nicknamed it le cochon, “the pig.” The Acela never actually achieves that speed, save on a couple of very short stretches of track in New England. Overall, it manages just about sixty-nine miles per hour — about the same as Amtrak’s regional trains, or the cars on the highways just outside its windows.

At dinner the first night out from Chicago is Jason, returning to his job laying pipe in North Dakota’s Bakken oil fields. A trim, big-shouldered man who looks younger than his forty years, Jason just celebrated his twentieth wedding anniversary in Michigan with his wife. The Bakken job pays well and he likes it, having worked in the past as a firefighter and a die maker for “a big company” at which he saved “a documented two hundred fifty thousand dollars over nine years, but never got a penny raise for it.” Now he is part of a twenty-eight-man crew in the fields, along with his brother-in-law and his nineteen-year-old son, whom he says he is glad to have the chance to keep an eye on.

In North Dakota, Jason lives with three other men in an RV, where he cooks and also raises and cans vegetables from his garden plot. Local food prices are at boomtown levels. For everything else he needs, he goes to the Walmart in Williston, though he reports that demand is so high now that the shelves are often empty, which forces him to travel some 125 miles to the better-stocked Walmart in Waterford Township.

At Minot, a small prairie city in North Dakota, the porters bring on stacks of the Minot Daily News, which boasts the most risibly far-right editorial page I have ever seen. There are two syndicated columns, one by Rich Lowry arguing that we don’t need any more gun-control laws, the other by Brent Bozell arguing that we don’t need any more gun-control laws, and a column by George Will mocking President Obama for not comparing the civil war in Syria to the Nazi blitz on London.

Will wrote an equally vitriolic diatribe in 2011 for Newsweek entitled “Why Liberals Love Trains.” In it, he scorned “the president’s loopy goal” of giving 80 percent of all Americans access to high-speed trains, citing the contentions of the Cato Institute’s Randal O’Toole that “high-speed rail connects big-city downtowns where only 7 percent of Americans work and 1 percent live,” and that the “average intercity auto trip today uses less energy per passenger mile than the average Amtrak train,” while “high speed will not displace enough cars to measurably reduce [traffic] congestion” and will in any case be too danged expensive.

All the practical reasons for promoting train travel, which Will sneers at for their “flimsiness,” are in fact of vital importance in a world where every day brings a new report from actual scientists that climate change is proceeding at a pace faster than anticipated. An average freight train expends slightly more than one twelfth the BTUs per short-ton mile as a heavy truck, while, as Tom Zoellner puts it in his book Train, “One trainload of passengers equals about a hundred city blocks of cars.” Amtrak expends an estimated 1,600 BTUs of energy per passenger mile, according to the U.S. Department of Transportation, compared with about 3,300 for buses, 2,500 for airplanes, and a whopping 3,900 for the cars that now besiege most American cities and suburbs in hours-long traffic jams. This is not even to mention plane travel — conspicuous in its omission from Will’s rant — in the course of which one is now X-rayed, wanded, patted, groped, deprived of shoes and belt like any other prisoner, then sausaged into an ever more crowded tube, charged for every minor amenity, and dropped at least a good hour and fifty dollars from one of those allegedly desolate downtowns we don’t need to reach anymore.

All the practical reasons for promoting train travel, which Will sneers at for their “flimsiness,” are in fact of vital importance in a world where every day brings a new report from actual scientists that climate change is proceeding at a pace faster than anticipated. An average freight train expends slightly more than one twelfth the BTUs per short-ton mile as a heavy truck, while, as Tom Zoellner puts it in his book Train, “One trainload of passengers equals about a hundred city blocks of cars.” Amtrak expends an estimated 1,600 BTUs of energy per passenger mile, according to the U.S. Department of Transportation, compared with about 3,300 for buses, 2,500 for airplanes, and a whopping 3,900 for the cars that now besiege most American cities and suburbs in hours-long traffic jams. This is not even to mention plane travel — conspicuous in its omission from Will’s rant — in the course of which one is now X-rayed, wanded, patted, groped, deprived of shoes and belt like any other prisoner, then sausaged into an ever more crowded tube, charged for every minor amenity, and dropped at least a good hour and fifty dollars from one of those allegedly desolate downtowns we don’t need to reach anymore.

Silliest of all Will’s charges, though, is his insistence that trains are “Archimedian levers” designed to make Americans “more amenable to collectivism.” Beyond the immense freedom that Amtrak trains in fact provide the individual to read, work, eat, drink, sleep, or stare out at the beauty of America, what stands out about any Amtrak train, at least in the day coaches, is the incredible diversity of the passengers. The usual categories only begin to scratch the surface. To walk through the Empire Builder at night was to pass scenes of incredible sweetness: couples snuggled together under blankets, mothers with babies in their arms, whole families of every possible color and age and creed strewn out over the seats and snoring uninhibitedly.

In the observation car, the Amish wedding-goers sat up together at two tables in the dimmed lighting — lighting perhaps no brighter than the oil lanterns provided when trains first rolled across these plains: the men dressed and bearded like Felty Miller, the women in long black or blue dresses and white bonnets, all of them talking and laughing quietly in their unique German dialect, members of one of the very first religious groups to find refuge in America from persecution. It struck me that Whitman would be right at home on the train, even if Will would not.

What is the appeal of train travel? Ask almost any foamer, and he or she will invariably answer, “The romance of it!” But just what this means, they cannot really say. It’s tempting to think that we are simply equating romance with pleasure, with the superior comfort of a train, especially seated up high in the observation cars. But having seen a rural train emerge silently through a gap in the New England woods, having seen the long slide of a 1 train’s headlights down the rails of a Manhattan subway station, I suspect that the appeal of trains is something more primitive than this. Trains are huge things that come upon us like predators. Almost from the beginning of the machine age, Americans yearned and sought ways for the train to connect their little towns — to connect them — to the greater world.

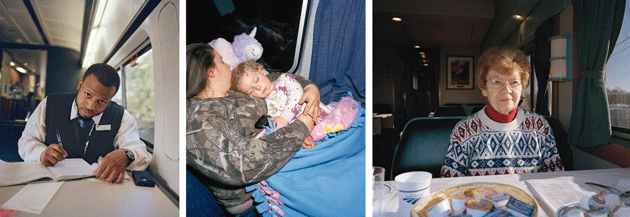

An Amtrak employee on the Silver Star. A mother and daughter travel from Cary, North Carolina, to Jacksonville, Florida, on the Silver Star. A passenger eats breakfast on the Crescent from New York to New Orleans as it passes through Charlotte, North Carolina.

Romance or not, it is this very practical desire that has probably kept Amtrak alive. The Republican right politicized train travel long before George Will and the Tea Party — almost from the moment it failed to expire on cue, in fact. David Stockman, Ronald Reagan’s budget director, dedicated himself to terminating Amtrak, denouncing trains as “empty rattletraps” and “mobile money-burning machines.”

Over the years, Republicans have pushed the question of Amtrak’s continued existence into that same strange sphere of debate in which they have isolated nearly all public institutions, save the military: not whether it serves a valuable social and economic function, but whether it makes a profit.

Highway advocates point to tolls and gas taxes as evidence that pavement is self-sustaining; rail’s supporters object that train riders are forced to pay such subsidies, too. Federal highway subsidies came to some $41.5 billion in 2013; federal aviation subsidies, to $16 billion. Amtrak, by contrast, received only $1.6 billion. All Amtrak’s subsidies for the past forty years — almost its entire existence — do not equal what the U.S. Treasury transfers from its General Fund to the Highway Trust Fund in a single year. To put it another way, each American citizen pays $4.07 a year to keep Amtrak running.

Whether even this amount will be forthcoming in the future is open to conjecture. Rail service has many friends but a limited constituency. There are just over 20,000 Amtrak workers; by comparison, New York City’s MTA system employs more than 70,000 people. Only 2 percent of Americans say they’ve ever set foot on an Amtrak train, and only 3 percent of American workers commute by local train. A cursory swing through the nation’s capital confirms what an uneven struggle the politics of trains really is. Amtrak’s leading defenders are only the rail service itself, ensconced in Washington’s Union Station, and the National Association of Railroad Passengers, a plucky nonprofit advocacy group with a membership of only 23,000, tucked away in a few rooms of a town house in an old neighborhood not far from the station.

And yet, so far at least, this uneven struggle has not worked out the way anyone expected, thanks not just to the fervor of trains’ defenders but also to the votes of Republican congressmen and senators, often from the region of the country I am passing through now. Amtrak is the only public-transportation link to the outside world for more than 300 of its stops — many of them in small communities scattered over the Empire Builder’s route through North Dakota, Montana, Idaho, and eastern Washington State. For years, Stockman’s desire to defund Amtrak was thwarted by Mark Andrews, an otherwise undistinguished one-term North Dakota senator who came to Washington on the coattails of Reagan’s sweep in 1980 but was determined to keep train service available to his constituents.

In recent years, Republicans have mostly confined themselves to their trivial if mean-spirited proposals for paring down train costs — what is perhaps intended to be a death by a thousand cuts. While Amtrak workers actually make less than private-sector employees in similar positions, the G.O.P. objects to their health-care and benefit plans. Other Republican congressmen have pushed the bold idea of replacing the café cars with vending machines, and there have been the frequent suggestions that our national passenger-rail service should simply be privatized and returned to the states.

How this might in fact work was demonstrated by Amtrak’s recent request that Colorado, Kansas, and New Mexico each chip in $40 million annually over the next twenty years — $2 million per state per year — to help keep the Southwest Chief line running along its current route. Even this small request for additional state funding has set off extended bickering and created a deadlock between the states involved — along with outcries from many of the small communities the Southwest Chief now serves.

An object lesson in what the train means to the small towns of the West is Shelby, Montana, hard by the Canadian border. The Empire Builder reaches it around ten thirty at night, running five hours behind schedule thanks to the freight traffic. Shelby was where the craziest of all Western booms took place, back in 1923 — boom and bust, all in one day. After an oil strike that drove the town’s population from 500 into the thousands overnight, Shelby’s leading citizens decided they might parlay their good fortune into becoming a permanent resort destination, provided they could host a fight for the heavyweight boxing championship of the world on the Fourth of July.

It was a typical Western dream: audacious, patriotic, idiotic, and quickly exploited by a grifter from back east. But Shelby’s town fathers were on to something. Theoretically, at least, it didn’t matter now how small their town was, or how far it was from any other population center. The railroad could magically alter time and space.

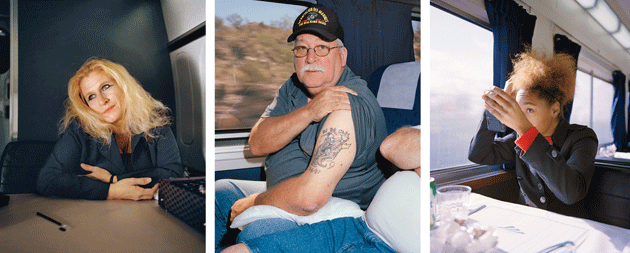

A commuter on the Silver Star to Miami. A former Marine returning to Onalaska, Texas, on the Sunset Limited from Los Angeles to New Orleans after a reunion with fellow Vietnam veterans. A woman on the Silver Star travels to Miami with her twin sister to celebrate their birthday.

“There was good railroad service into Shelby along the tracks of [the] Great Northern [Railway],” Roger Kahn wrote in his 1999 biography of boxing legend Jack Dempsey, A Flame of Pure Fire. “Fight fans could come in on coaches and Pullman cars from Spokane and Seattle and San Francisco, or from Grand Forks and Minneapolis and St. Paul, even Chicago and New York.”

The trouble was that the railroads, never quite believing the town could pull off the big fight, declined to run any special trains. Just under 8,000 paying customers showed up, in an age when heavyweight-title bouts routinely attracted 100,000 spectators. By the time it was all over, every bank in the area had gone bust, and Dempsey’s nefarious manager, Doc Kearns, was stuffing the last of the town’s money into a suitcase and running for his train, while the locals discussed whether to string him up from some nearby cottonwoods. “Lonely-looking trees they were, at that,” Kearns would remember.

Seen from the train, Shelby today is little more than a gas-station sign looming out of the darkness. But it’s a working town of more than 3,000 citizens, out here in the illimitable Western prairie, still served twice a day by the Empire Builder.

The next morning breaks bright but turns appropriately overcast as we snake our way down along the bank of the Columbia River and into the rain shadow of the Rockies. This is ominous-looking, barren country, studded with desolate gray and brown hills. It is another industrial landscape, with enormous machinery scattered here and there, but the only sign of human activity to be seen is another train, making its way along the south bank of the wide, slow river. The clouds hang lower, but the hills grow steadily more steep and wooded, each passing scene more dramatic as we approach the Pacific.

View from the window of a Crescent traveling through North Carolina after a night of snowstorms and delays.

I catch the Coast Starlight out of Portland’s pretty redbrick-and-stucco Union Station, with its high clock tower and its mural of Lewis and Clark inside. The Coast Starlight is the closest thing Amtrak has to a 20th Century Limited — to an elite carrier — even if the differences from its other long-distance lines are trivial. A voice purrs quietly over the public-address system, urging us not to bother our fellow passengers too much by using cell phones. A complimentary split of champagne and a wine-and-cheese tasting are on offer in the “parlor car.”

There are “wine tastings” on many long-distance Amtrak trains, but this usually means a few plastic cups of table red. On the Starlight, local vintages and artisanal cheeses are served in actual glasses and on real plates, and they are presented with copious guides to what we are about to devour and which bottles will be available for purchase. It’s all wittily moderated by a train steward with a steady comic patter, much to the delight of a small English tour group and an Australian family of three, who are reduced to almost nonstop laughing and snorting by the wine and japes.

The parlor car was built for the Atchison, Topeka, and Santa Fe Railway in 1955, during the last gasp of opulent train design. It has cut-glass booth dividers with the name and logo of the legendary, long-vanished railroad it was intended for, and well-crafted corner cabinet bookcases that hold a few musty books, magazines, and board games. Downstairs is a tiny movie theater that shows a children’s film during our imbibing and, later on, the most recent Great Gatsby for the adults.

The Coast Starlight does not really travel along the coast until San Francisco, but we do pass through lush river valleys and alongside well-heeled small towns, suburbs, and country homes.

California was supposed to be where President Obama’s vision for the future of rail was to become reality. In theory, his plan was a good one. It called for immediate upgrades on “existing infrastructure to increase speeds on some [Amtrak] routes from seventy . . . to over a hundred miles per hour.” This would be followed by longer projects to create true high-speed-rail systems on thirteen major corridors throughout the United States, each of them one hundred to 600 miles in length and running between multiple urban centers. It was, in short, a plan to replicate what already works — Amtrak’s Northeast Corridor — all over the country, and make it better, maybe building a permanent ridership for trains in the bargain.

The trouble came, as it so often does with Mr. Obama, on the follow-through. The $9.3 billion he requested for railroads in the first stimulus proposal was a ridiculously small amount for the project at hand — one that signaled through its size alone what a low priority rails really are for this administration. Of that $9.3 billion, a mere $1.3 billion went to upgrading existing Amtrak operations, partially through the purchase of seventy new, badly needed electric locomotives. The remaining $8 billion was allocated to the planned high-speed-rail corridors. This was barely enough to build a hundred miles of track. The original thirteen proposed corridors were narrowed down to four, in California, Florida, Ohio, and Wisconsin. But none of these plans was put into place before the 2010 elections swept Democratic governors and legislatures out of power in Florida, Ohio, and Wisconsin. Their Tea Party replacements gleefully renounced federal money for the train corridors as “high-speed boondoggles.”

The one exception was California, where Jerry Brown was back as governor and where voters had already approved a referendum authorizing the state to spend $9.95 billion to build new trains that could travel from Los Angeles to both San Francisco and Sacramento, and do it in no more than two hours and forty minutes. The federal government has now pledged some $6.4 billion of the original $8 billion designated for fast trains to the California project, with the hope that it will be completed sometime in or around . . . 2033.

It has been determined that at least 40 percent of the new rail will be elevated, with an estimated 22,000 enormous concrete pillars carrying the train through earthquake-prone California and replicating the very sort of hated elevated urban highway that so many cities have just spent decades tearing down at enormous cost and trouble. Even in the depressed farming communities of California’s Central Valley, where the first leg of this monstrosity is supposed to take shape, opposition has been intense. Governor Brown, however, has remained committed, ridiculing the plan’s opponents as “fraidy cats” and “fearful men — declinists who want to put their head in a hole and hope reality changes.” But the changing reality proved to be the system’s projected costs, which started at an estimated $42 billion, then rose to $68 billion — or $190 million a mile, enough to run two public high schools for a year. By the end of 2013, Brown was in China, still seeking additional funding for this El to nowhere — now estimated to cost more than $91 billion.

If, as Zoellner writes, the American rail system today is an example of “technological regress,” the Obama fast-train project is political regress. A large and immediate commitment of money to upgrade successful existing Amtrak trains — increasing their speeds and frequency, making their service and safety better, reducing their price — might have bolstered a growing constituency for mass transit while providing jobs, improving the environment, and supporting smarter growth. Instead, the Obama Administration’s failure to move with alacrity, clarity of purpose, or even basic competence has probably doomed not only its own efforts but a critical national project.

Whether or not California’s fast rail will ever reach San Francisco, no Amtrak train goes there today. Now a trip back across the continent starts with a predawn bus pick-up along Fisherman’s Wharf, for delivery to another Amshack, in Emeryville, a generic northern California suburb where there is not a hint of, say, a hotel. An electronic board lists all of two local trains; a sign next to it announces that the two long-distance lines here, the Coast Starlight and the California Zephyr, will not be listed on the board.

The Zephyr runs across both the Sierra Nevada and the Rockies, back through the heart of empire. By the afternoon, we are climbing steadily through the foothills of the Sierras, passing just north of where gold was discovered at Sutter’s Mill in 1848, setting off the daddy of all Western booms. Soon we are between 1,500 and 1,800 feet above the American River, then the Bear River, revealed to us in one stunning vista after another through the mountain woods, territory so absolutely beautiful that all we can do in the observation car is snap away with our cameras or phones, or sit helplessly mumbling superlatives.

The northern banks of Lake Pontchartrain seen through the window of a City of New Orleans bound for Chicago.

At 7,000 feet, we reach the pass where the Donner party came to grief, resorting to murder and cannibalism when their wagon train was caught by the first mountain snows, though their fate was exceptional. Planning their trips with incredible care, almost every other wagon train made it through. Even so, only about 200,000 pioneers had followed the Overland Trail to California by the time the Civil War began. The journey took five to six months, and the only alternatives — traveling around Cape Horn or across the fever-ridden Isthmus of Panama — were full of worse perils.

A young railroad man from Connecticut had another idea. Theodore Judah talked so obsessively about the idea of building a railroad across the continent that people began to call him Crazy Judah. By 1860, after four years of searching, he was sure he had found his route — the one we are taking now through the Donner Pass.

The transcontinental railroad proved a remarkably easy sell, even with the country about to lurch into civil war. In part, the Union wanted it as a way of keeping California and Oregon attached to the country. Yet well before the war, America was sold on the idea of a continental road — its leaders and opinion makers remarkably prescient about the prospects of global trade. For John C. Frémont, the transcontinental meant that “America will be between Asia and Europe — the golden vein which runs through the history of the world will follow the track to San Francisco, and the Asiatic trade will finally fall into its last and permanent road.” Asa Whitney, a New York dry-goods merchant, wrote in 1845:

You will see that it will change the whole world. . . . It will bring the world together as one nation, allow us to traverse the globe in thirty days, civilize and Christianize mankind, and place us in the center of the world, compelling Europe on one side and Asia and Africa on the other to pass through us.

In reality, the transcontinental railroad was not merely ill conceived but actively destructive, according to historian Richard White, who makes the case in his 2011 book, Railroaded, that all the rail lines eventually built through North America were run by “inefficient, costly, dysfunctional corporations” and should not have even been attempted. In their immaturity, White maintains, they were “failures as businesses” that started repeated financial panics; “helped both to corrupt and to transform the political system by creating the modern corporate lobby”; “flooded markets with wheat, silver, cattle, and coal for which there was little or no need”; wrecked communities, including many Native American nations, as well as individuals; crushed their own workers; and “yielded great environmental and social harm.”

White’s criticisms are inescapable, but they seem more an indictment of the nation and the age than of the railroad itself. Certainly the Native American peoples east of the Mississippi fared no better than those to the west, even if it took white settlers — without trains — centuries longer to overrun them. Booms and busts had roiled America from the time of the Jamestown Colony, as had financial chicanery since at least the moment the first government bonds set Wall Street in motion. The railroad was not so much a cause as a symptom or a tool.

What remained, though, was that prophetic nineteenth-century vision of America at the center of the world, strategically situated between the economic powerhouses of Europe and a resurgent Asia. And, of course, the physical reality of the railroad itself.

Abraham Lincoln enthusiastically signed the Pacific Railway Act of 1862 into law with almost no opposition from Congress. His government chartered both a Union Pacific Railroad company, to build west from the Missouri River, and the Central Pacific Railroad, to build east from Sacramento. Both companies would be granted ten square miles of land for every mile of track laid — an enormous government giveaway. Government bonds would raise $16,000 a mile for construction over flat land, $32,000 a mile in the high plains, $48,000 a mile for the passage through the Sierras and the Rockies.

Despite this subsidy, nobody was sure the job could be done. The Donner Pass route that Judah proposed might be compared to a great ramp up the mountains from Sacramento. Climbing it today, we can still appreciate how gradual it is, perfect for a means of conveyance clamped around two metal rails. But just past Donner Lake was a thousand-foot rock wall, and all along the route were granite ridges, liable to sudden rock slides and thirty-foot snowfalls.

The work required 13,500 men to hack away at the Donner Pass with the most primitive of tools — picks and shovels, wheelbarrows, and one-horse dump carts. Progress slowed sometimes to as little as two or three inches a day. The solution was nitroglycerine and Chinese immigrants. The former had to be concocted on-site, after a shipment annihilated a San Francisco dock and killed fifteen people. But the largely Irish, immigrant workforce still wouldn’t touch the stuff, and the Central Pacific resorted to the almost entirely male population of Chinese laborers who had come to California chasing the Gum Sham, “the Mountain of Gold,” only to be ostracized, persecuted, and frequently lynched by local whites.

The Central Pacific loved them, eventually hiring some 12,000 Chinese men — who would work for lower wages than white laborers demanded and made up about 80 percent of the workforce — to bring the road through the mountains. Lowered along the rock walls in gigantic baskets, they drilled holes fifteen to eighteen inches deep, poured in the nitroglycerine, capped the hole, then set the nitro off with a slow match. They worked carefully and well, but the real benefit to the Central Pacific was that nobody much cared how many of them got blown up. Estimates vary widely as to how many died cutting their way through the Sierras, obliterated by the nitro or crushed under the rock slides it set off. It was carnage enough to provoke even these desperate men to go on strike, though they won a raise of only five dollars a month.

The California Zephyr climbs steadily along Judah’s great ramp, moving all the while past what remains of the rustic mountain towns founded to help build the railroad and support its operations. At 4,700 feet, we pass Blue Canyon, once a town of more than 3,000 people, with water so pure and delicious it was considered the best in the West and was served on all South Pacific Coast trains. Today the town consists of a few scattered houses, half-hidden in the woods. We pass Gold Run, where hydraulic engines lifted millions of dollars’ worth of gold out of the ground before the mines gave out and the town was abandoned, and Cisco, a supply depot 5,938 feet above sea level where more than 7,000 people once made their home — now no more than a few houses and some rusting sheds next to Interstate 70.

After Lake Spaulding, we move into a long snowshed, built to protect passing trains in the event of an avalanche. Once there were thirty-seven miles of them, snaking their way through the mountains. Sparks from the old engines routinely set them on fire, but the railroad work crews kept rebuilding them. Supposedly, one third of all the forest in California was chopped down to provide the timber for them, and for all the bridges and the work sheds and the ties needed to build the railroad and keep it running. Near Norden, another tiny community, we pass the Summit Tunnel, the peak of the railroad in the Sierras, where the Chinese blasted their way through 1,649 feet of solid rock, making a way that passenger trains and freights used continuously until 1993.

After Norden, we descend in a series of dazzling, miles-long switchbacks, the end of our train visible on the mountain plateaus above us, and pass Truckee, a flourishing resort town that in the late nineteenth century held fourteen lumber mills and countless saloons and burned down six times in its first eleven years; then Verdi, a tiny community with a large trailer park; and Boca, a once-thriving lumber and ice-harvesting town that went bust when the sawmill shut down and the hydroelectric dams brought electricity, and now all that remains is the ruins of its vaunted brewery and a few crumbling bridges over pretty little trout streams.

This mountain scenery is so infectious that it makes us giddy in the observation car, where we continue to chatter and take pictures. At dinner I sit with two of the friendliest people from our long afternoon over the mountains, Lilly and Jackie, a mother and daughter from California. Lilly lives in Sacramento, her daughter in Stockton, which she staunchly defends, claiming the media has it in for her town.

They are traveling together now on a sort of grand tour, going to see friends and relatives in Chicago, Washington, D.C., Virginia, and Atlanta. Lilly was married for many years to an Air Force man, and they had seven children and lived all over the world. Jackie remembers being most impressed by the cherry blossoms and the 1964 Tokyo Olympics, when their family was stationed in Japan.

Jackie relates stories from her twenty years as a federal corrections officer. She tells us about drug couriers who tried to smuggle their contraband into the country inside dead babies, and about the racketeer Michael Milken, whom she calls a rascal, and Heidi Fleiss, whom she calls ugly and says was stoned when she first reported to prison. She is afraid that she became too paranoid during her years as a guard. She is proud of her knowledge of guns and self-defense, but found that for months after she retired she would catch herself searching her home for places where someone might conceal a weapon.

The scenery changes the moment we get out of the mountains, the way it does so often across America. From the train, most of Nevada looks like exactly what it is, the bed of an ancient sea, a landscape broken only by the remnants of more bridges, tiny clusters of houses, and distant highways on each side of the tracks. The exposed desert rock glows softly in the dusk, a drowsy, pastel sunset after the dramatic landscapes of the Sierras.

The headlines on the bundles of USA Todays brought aboard read HOUSE, SENATE PARRY ON ‘OBAMACARE’ AS SHUTDOWN LOOMS. It’s not of much concern on the California Zephyr. At breakfast, I reminisce with Gene — a devout Nebraska Cornhuskers fan wearing a bright-red team jacket, on his way back to Lincoln, where he has been teaching mathematics for fifty-three years — over Johnny Rodgers’s greatest game. At lunch, I talk to Leah and John, both of whom have their pilot’s licenses and have lived and worked all over the world in public health, about Mayor Dick Lee and his struggle with the Model Cities program in New Haven, Connecticut. We speculate about a middle-aged couple who hold hands everywhere they go on the Zephyr, and whom everyone wonders about until we realize that the man is blind. I marvel anew at the range of conversations you can have on the train even as you’re being Archimedied into collectivism.

Traveling north through central Oregon on a Coast Starlight from Emeryville, California, to Portland.

As it happens, the Zephyr is unable to take its usual scenic route through the Rockies because torrential rains have washed out the track near the Moffat Tunnel — the second washout due to extreme weather I’ve encountered within a week of travel. Suddenly, we are in a tale foretold. Ayn Rand — the devoutly atheist cult leader who has somehow become the prophet of fundamentalist Republicans — loved trains. In her major opus, Atlas Shrugged, one of her great heroes of capitalism — her “prime movers” — runs a railroad. In doing research for the book, Rand supposedly rode in locomotives of the New York Central and even operated the engine of the 20th Century Limited, later claiming, “[N]obody touched a lever except me.”

When the prime movers of Atlas Shrugged decide to go on strike until they are properly appreciated, trains are transformed into tools of almost biblical retribution. They plunge off a bridge into the Mississippi, or asphyxiate all aboard in a badly ventilated mountain tunnel, or simply stop in an Arizona desert, leaving its passengers and crew to be rescued by a passing wagon train (!).

Here, then, is Rand’s prophecy, much echoed in recent years by Republicans from Mitt Romney on down, though usually with reference to Europe. It is finally happening! Our indulgent, unaffordable welfare state has caused our entire civilization to collapse!

Except the employees of Amtrak have made provisions for this contingency. It turns out that somehow we are not to be choked to death in our compartments or turned out to wander the prairie like so many buffalo, just rerouted through Wyoming, where we will be following the rail bed of the original transcontinental railroad.

We are hustled through the state like Lenin being carted across Germany to Russia in his sealed railway carriage during World War I. No one is allowed off the train at the brief stops, even to stretch their legs, lest we contaminate the good citizens of Cheneyland with our collectivist ways. The only exceptions are a couple of passengers who have brought dogs. We watch enviously from the windows as they cavort through the high prairie grass with their pets during a stop.

Wyoming is almost unbelievably empty, even compared with the rest of the West. Mile after mile, there is nothing: no visible water, no sign of human habitation beyond the snow fences along the tracks, just two steel lines moving across the land. An Army topographic engineer once called the high plains west of the Mississippi the Great American Desert. The region averaged less than twenty inches of rain a year, and much less during its years-long dry spells. Blizzards and long cycles of drought killed off the settlers’ cattle. Locusts devoured their crops. Even in the good years, they often lived in sod houses infested with spiders, snakes, and centipedes, and burned buffalo chips as their only source of fuel.

Against this dispiriting reality, the railroads took up with land speculators to turn the Great American Desert into the Great Plains and “the Garden of the World.” Posters and pamphlets promised “Riches in the soil, prosperity in the air, progress everywhere. An Empire in the making!” A booster invented that dangerous absurdity, “Rain follows the plough!” The more the settlers churned up the earth, they were promised, the more moisture would be absorbed into the soil and circulated back into the atmosphere. The Atchison, Topeka, and Santa Fe insisted that the “rain line” moved west with its tracks, the steam from its engines condensing into clouds. Pseudoscientific properties were attributed to the steel rails themselves, or to the electrical impulses leaping along the new telegraph wires, or even to loud noises. If all that failed, farmers were urged to embrace “dry farming” — plowing furrows twelve to fourteen inches deep, then harrowing their fields after each rainfall.

When it was finally conceded that the West could not be the East, the area was reconceived as a sort of colossal factory. Almost anything that could be extracted was cut down, torn up, dug out, shipped east by rail, then processed and shipped on again. Between the Civil War and the Great Depression, new industrial booms followed one after the other, in cattle, in timber, in coal and other minerals — even in bison meat. The railroad was, once again, its conveyor.

When World War I disrupted wheat exports from Russia, farmers on the high plains found a bonanza selling their wheat to Europe. They poured their newfound cash into mechanized plows and reapers and tractors and got rid of many of their work animals, freeing up another 32 million arable acres formerly dedicated to pasture. Wheat production grew 300 percent in the 1920s — but all this succeeded in doing was driving down the price of wheat. Desperate farmers responded by plowing up increasingly marginal land. The buffalo grass that had stitched the Western plains together for 35,000 years was gone overnight.

The end was an ecological as well as an economic catastrophe. With the next, entirely predictable cycle of drought, the dust started blowing, in 1932, and didn’t stop for a decade. A huge oval of land on the plains, roughly 100 million acres, 400 by 300 miles in size, soon lay desolate. The dust was everywhere, covering farm machinery and entire houses, piled up against barns like Saharan sand drifts. One third of the Dust Bowl’s inhabitants — 250,000 people — ended up leaving. In a generation, as the historian Donald Worster points out in his book Dust Bowl, much of the region had gone “from a spirited home on the range where no discouraging words were heard, to a Santa Fe Chief carrying bounteous heaps of grain to Chicago, and, finally, to an empty shack where the dust had drifted as high as the eaves.”

No traces of that devastation can be seen today. The discovery of aquifers (now rapidly being depleted) and the creation of farm subsidies and government conservation and resettlement programs allowed for the land to be restored — at least for the time being.

The trains, too, got taken in hand, by private enterprise and government alike. J. P. Morgan and others snapped up as many lines as they could. Populist and progressive revolts gave the Interstate Commerce Commission unprecedented powers to regulate rates and conditions. With our entry into World War I, every train in the country was nationalized under the U.S. Railroad Administration. This practice proved so efficacious that after the war the ICC proposed a comprehensive national plan to consolidate the rails, though it was never implemented. In the 1920s, the United States still had 1,085 railroad companies. But the mergers of many rail lines during the 1930s and more forced consolidation by the government during World War II succeeded in creating by the 1940s a more rational system.

The dining car on the Zephyr loses its air-conditioning when its electrical board malfunctions, and the kitchen becomes unbearably overheated. The menu is limited, but the staff remains remarkably helpful, and we are not asphyxiated. We move south, into Colorado, and actually reach Denver early, because of the detour. Dinner is served while we are halted on the tracks just past the center field of the Colorado Rockies’ park, Coors Field, finished in 1995 at a cost of $300 million.

The next morning, we push through into the farm country of Nebraska, then Iowa. The kitchen stays down all the way to Chicago. For a day and a half, and a dozen stops, no one has the wherewithal to fix the malfunction. On board, the bloom is off the rose, thanks to the sheer length of the trip. We resort more and more to the subterranean café car, run this time by Carol, a perpetually angry attendant, who treats any efforts at empathy with marked hostility. When someone remarks that she will surely be glad to see Chicago at the end of the sweaty, fifty-three-hour voyage of the Zephyr, Carol snaps, “Why? I hate the city!”

I skip the Metropolitan Lounge on the trip back to New York, preferring to sit in a dark, beery commuter bar in Chicago’s Union Station. But the Lake Shore Limited is cheery and bright, and another helpful steward serves us complimentary wine and cheese.

He gives a leftover half bottle to a couple in their thirties. They laugh and smile and hold hands in the club car. They speak glowingly about all they have seen on the way out to Spokane, where Lisa had a speaking engagement, and back, the lights of the oil and gas fields at night in North Dakota, the beauty of Glacier National Park by day.

He gives a leftover half bottle to a couple in their thirties. They laugh and smile and hold hands in the club car. They speak glowingly about all they have seen on the way out to Spokane, where Lisa had a speaking engagement, and back, the lights of the oil and gas fields at night in North Dakota, the beauty of Glacier National Park by day.

Eric works mostly in Maryland and Washington, but he owns a home and fifty acres in Binghamton, New York. He’s hoping that it will attract a fracking company — the great dream of everyone in upstate New York not looking to hook up with one of the four casinos recently promised to the region — and he dismisses any environmental concerns: “If you look at the science, it’s perfectly safe.”

In the morning, we pass the ruined cities of upstate New York again. By afternoon we are headed back down through the dappled autumn loveliness of the Hudson, to New York City and Penn Station. We plunge back under Riverside Park, the sort of structure we used to routinely build above our buried trains, with what was then our endless talent for practical and gracious innovation. But today a journey of more than 7,000 miles, into our greatest city, ends where it began, the disembarking passengers staggering along a drab, dimly lit concrete platform. “One entered the city like a god; one scuttles in now like a rat,” wrote the architectural historian Vincent Scully after the original Penn Station was torn down, in 1963.

That building, designed by Stanford White, was a symphony in glass and steel, clad in pink Milton granite and honey-colored Travertine; lit through lunette windows, and festooned with clocks and map murals of the great nation it stood in tribute to. It was something “vast enough to hold the sound of time,” as Thomas Wolfe wrote in You Can’t Go Home Again.

But when it was thought that something more profitable might be built in its stead, its vaulted glass roofs were smashed with wrecking balls and its granite and marble walls were jackhammered to pieces. Its graceful Greek columns were sawed through, and its great clocks, its carved-stone eagles, and the maiden sculptures that represented Night and Day were pulled down and taken over to New Jersey, where they were dumped in the swamps of Secaucus, like the body of a murdered mob stoolie.

“The message was terribly clear,” Ada Louise Huxtable wrote in the New York Times. “Tossed into that Secaucus graveyard were about 25 centuries of classical culture and the standards of style, elegance and grandeur that it gave to the dreams and constructions of Western man.”

In addition to being beautiful, the old station was the pinnacle of an immense technological achievement, a vast network of infrastructure that included two rail tunnels under the Hudson River, four more under the East River, and the Hell Gate Bridge. To build the Hudson tunnels alone, crews of sandhogs dug toward each other beneath the river for three years, under intense heat and pressure, behind 200-ton iron cylinders or shields. Finally, “the shields met, coming together rim to rim,” in the words of the historian Lorraine Diehl, “like two gargantuan tumblers.” For the first time, America was connected by rail from Montauk to San Francisco.

“It was one of those rare architectural masterpieces that are able to touch man’s soul,” Diehl wrote of the station that so fittingly crowned it. “Built as a landmark, it was a monumental gateway meant to last through centuries.”

Instead, it lasted a little more than fifty-three years. When the decision was announced, in 1962, the only protesters were some 200 people, mostly architects and academics. Few others seemed to care. Officials posed smiling for pictures next to the lowered eagles. “Just another job,” said John Rezin, the foreman of the demolition crew. “Fifty years from now, when it’s time for our Center to be torn down, there will be a new group of architects who will protest,” Irving Felt, president of the Madison Square Garden Corporation, predicted.

It has been another fifty years, and not only architects but many New Yorkers in general would gladly take Madison Square Garden apart by hand if it meant a chance to see a new Penn Station rise. But nothing gets done. The Garden was stuck atop the grave of the old Penn Station back in the 1960s because white commuters were supposedly too afraid to venture very far into the big, bad, black city — about as terrible a perversion of urban planning as has ever been practiced. Ironically, the scariest people around the new Penn Station are the drunken suburban louts in their Rangers jerseys on game night.

Plans for building a twenty-first-century train station in the Beaux Arts central post office across Eighth Avenue from the Garden have been on the books for twenty years now. Architects have churned out any number of wondrous fantasies of what a new station might look like. But the Garden and its teams are owned by a thuggish cable-TV heir who stubbornly holds out against any intrusion on his ugly cash cow. Amtrak, citing money worries, still hasn’t fully committed to the proposed new facility, to be dubbed Moynihan Station (in honor of former New York senator Daniel Patrick Moynihan, a leading rail advocate), and all the grand plans aside, it’s unclear what passengers would get in the end — maybe just a bigger Amshack.

As one state official told the New York Times architecture critic Michael Kimmelman in 2012, the “project aspires to be more like the Frank R. Lautenberg Station in Secaucus, N.J.”

We have always been a country of boom and bust, and a rail has always run through our wildest schemes. The train was a wonderful tool that came into being before anyone, even the men who owned it, really knew what to do with it. As with the rest of our democracy, it was the learning, the mastering of these men and their machines, that would eventually provide us with some measure of what this country has always personified.

We did incredible things with trains. We ran them through mountains and deserts and under rivers and swank avenues and beautiful buildings. We turned them into rolling luxury hotels and made them into something so extraordinary that adults as well as children came running just to watch them as they passed. We learned how to coast them into stations without their locomotives and how to string whole cities of commerce around them. We looked a hundred, two hundred, three hundred years into the future, and built railroads to match our vision. Then we discarded trains as something hopelessly antiquated and unnecessary.

The America we live in today does not even have the political will to connect a train to a platform in many places, much less build a new generation of supertrains. Amtrak and its supporters remain confident that it can endure, even triumph, and they may be right. Trains still have advocates even in the reddest of Western states, and unlike so many of the public-sector areas that the right’s corporate sponsors would like to fully privatize — education, health care, prisons — no one seems eager to get their hands on a passenger rail system.

But the odds are just as good that Amtrak will vanish completely. Against the rigid ideology that now drives the Republican Party, the old politics of horse-trading and constituent services may not suffice. The government shutdown ended twelve days after we pulled back into the bowels of Penn Station, a big defeat for the Tea Party movement. But within weeks, its memory was obliterated by the Obama Administration’s botched rollout of its already woeful health-care plan. The unwillingness of the Democratic leadership to commit to any public good has already disfigured the liberal idea, and its continuing failure may well sweep our national rail service away, along with everything else. For all Amtrak’s shortcomings, losing it would be a very bad thing. The train muddles through wonderfully, given all the restrictions we put on it. We are capable of more — or at least we used to be.