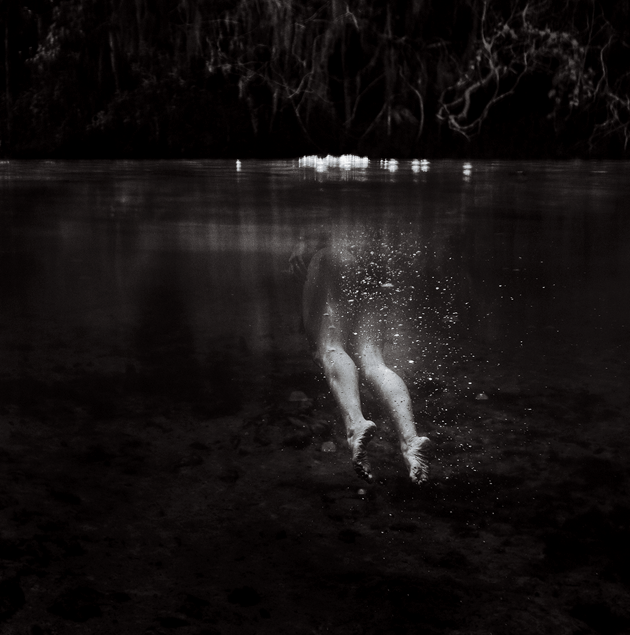

The lake is still and the stars are mammoth. She glides beneath the surface, a dark form he can follow but cannot see until she passes through starlight, this long-limbed woman who had been his wife — sweeping arc of arms, black tongue of hair, pincer thrust of legs — appearing and vanishing, as she swims constellations.

A crying baby yanks him from the dream, but there is no baby, merely wind troubling the lake, the metallic complaint of the trailer, a woman’s mournful, amused voice: “. . . sort of like a battleground seen from the air.” She holds a paperback, a hooded bulb clipped to the pages, the spray illuminating the muddled landscape of scars along his thigh. A lozenge clicks against her teeth, adding a rhythmic tap to her observations. “Or it could be a marsh,” she decides, “with wetlands all around it.”

The Airstream’s bed is narrow. Her body presses against the full length of his, the ice of her feet against his ankles. She has a fruity, powdery smell. This is their first time together, and he is not yet wakeful enough to claim her name.

“Rob and Laura Petrie slept in twin beds,” she goes on, shifting the light to his face, “and those beds were both wider than this thing.”

In the cave of radiance created by the book light, Paul blinks and breathes, his mouth forming vowels. How deeply he submerged after sex, a brief chilly slumber and the chill is still with him.

“You like old TV,” he says. “You and your dad watch it together.”

This testimony pleases her. “It’s nice to be with a boy — or man, I guess — who listens. I can put the book away if you want to do it again.”

Her body is plump and pale, pliant and inviting, topped with a nicely shaped head, ordinary brown hair, an open, eager face: big smiling eyes, tiny cagey mouth.

“Too sleepy,” he says. Her name is Melinda Bell, this woman beside him, whose feet are glaciers sculpting his shins.

“Okay, then.” She returns to her book. On her shoulder, the tattoo of a rectangle.

Paul has slept with several women since the demise of his marriage, none of whom resemble his wife. I’m not like other people: the first words Benz ever spoke to him. They lived on the same street, and she liked to garden: kneeling in the yard (cutoff jeans, a sleeveless blouse), watering purple flowers with a coffee can (tan shoulders, the curve of bone beneath the skin). They exchanged glances but not words until he was walking home one morning from sausage and eggs at Al’s Breakfast. She was trying to stuff a thin mattress, folded like a slice of bread, into the back seat of a car.

“Most people take the sheets and pillows off before moving a bed,” he told her.

“I’m not like other people,” she replied.

A man’s voice called from the house: Quit being so fucking dramatic.

Paul hesitated, calculated, edged closer. “I’ve got a pickup that’ll fit it.” He drove an old Dodge Colt, but his roommate owned a white Tundra. This was Minneapolis, miles and years from Bony Lake. Now Paul lives in an ancient Airstream, and the woman sharing his bed clatters hard candy against her teeth while she reads.

“Nine-letter word for a kind of service,” Melinda Bell says the following morning. She stands on the balls of her pink feet at the kitchen counter, one hand twirling a yellow pencil, a coffee cup making delicate clouds that rise to the aluminum ceiling. She wears the white waitress blouse and possibly underwear.

“Funeral,” Paul says. It’s early, the lake smeared with uncertain light, the trailer filled with the smell of coffee. They met at Lew’s All Nite. Paul pours drinks, Melinda serves tables.

“That’s seven letters.” Her thighs are as white as the birch trees that crowd the far shore of the lake. “This is a cute mobile home. How long’ve you had it?”

“Since I burned the house down. Three years, give or take.”

“I read about the fire. I was in a journalism class at the junior college that I had to clip things for and I clipped that story.”

His bones soften. “I never read any of the articles.”

“You can’t expect me to still have the clippings. I didn’t even finish that class.”

“Selective,” he says. “That’s nine letters.”

“Aren’t you the one.” On tiptoes still, she bends down to kiss him. Her breath smells of cherry candy, which smells nothing like actual cherries. She says, “I’ve got time if you want to do it again.”

“Maybe after coffee.”

“You men,” she says. “I know how you are.”

Blood is not always thicker than water. In the whole of the twentieth century, the Iris clan floated just two offspring to the shores of adulthood. Paul Montgomery Iris, thirty-year-old bartender ensconced in a miniature silver trailer, represents the tail end of the austere procession.

His grandfather Colman Sheelin Iris moved to Minnesota from Brooklyn in 1892 and built a house at the water’s edge, clearing the land himself, hauling timber to the sawmill on a wagon pulled by four spotted horses — Priam, Troilus, Hector, Aeneas. He used the horses like men to help with the construction: by means of harness and pulley they turned the big auger and raised the great timbers. When it was complete, the house was two stories connected by the narrowest of stairs, a cathedral-framed landmark of which Colman was intensely proud, permitting no renovation, not even electrical wiring or indoor plumbing. It appears in early photographs of the lake — tall, gaunt, unpainted — bordered by a narrow dock, attended by a barn and chicken coop, a vented outhouse, and a perimeter wall of stripped, vertical logs.

Colman kept Holsteins and fowl, selling eggs, milk, butter, and walleye to a local mercantile, and it was there in the spring of 1917 that he heard the story of a girl from the north who had lost her parents and needed a husband. The parents had taken ill at the turn of the year, were dead by February. The girl could not make her way off the farm until the weather broke. She harnessed a sled to her narrow shoulders and pulled her parents’ frozen bodies to the nearest town, Pine River, Minnesota.

With four horses, a light load, and good weather, Colman managed the trip to Pine River — 130 miles — in eight days. He found her to his liking: Aesa Fett, a tall, hardworking, lovely girl. The family that had taken her in did not want to let her go, but Colman had traveled too far to be dissuaded. He told her to meet him in the road after the family had gone to sleep. She obeyed, coming to him in a spring snowstorm, carrying a leather suitcase that had belonged to her father, a cast-iron pot that had been her mother’s. She was thirteen years old; Colman, sixty.

The snow did not let up, winter returning like a curse. On the ninth day of their passage, one of the spotted horses collapsed. Another crumpled in the road the following afternoon. Colman had no choice but to let the weather bury them. The return trip took eighteen days. He kept Aesa beneath a blanket in the wagon on the long ride, but his left hand, which held the reins, suffered frostbite. He would lose two of the fingers.

When they finally reached Bony Lake and the wagon was within the walled confines, his hands could not flex to lift Aesa, who climbed, as he directed, onto his back. He ferried her through the drifts and into the house, where he built a fire in the stone hearth before closing and locking the gate, stabling the horses. A third died that night. Aeneas was the only of the horses to survive the expedition, and he was no good for work thereafter, sway-backed, skittish, and frail, lacking the fortitude to carry even a child.

Lew’s All Nite was a dark tavern attractive to serious drinkers. It had no piped-in music, jukebox, or television; no darts, pinball machines, or pool table. Behind the bar hung neon signs for extinct beers: Falstaff, Griesedieck, Blatz, Blind Man Ales, Hamm’s, Lucky Lager, Meister Bräu. Centered among them was a brightly lit aquarium with no fish. The All Nite was not a place for optimists.

“Hey, genius,” a regular called, a woman in her late thirties named Kay Timmons, a gin drinker, who liked to talk, who needed his attention, who would tip him a twenty on a thirty-dollar tab. “If you’re so smart, why’s my glass empty?”

Paul responded immediately, “Nobody thinks I’m smart but you.”

“I’m putting all my eggs in that basket,” Kay told him. “Be kind to my eggs.” She seated herself on the same stool every Friday night, pretty in the Disney fashion — long hair the blond of Diet Sprite, lipstick the color of a fire-alarm box. Only her eyes didn’t fit the image, a rawness about them, like undercooked eggs. Her husband drove in the demolition derby, and she came to All Nite while he crashed motorized vehicles. “He makes fifty dollars,” she told Paul. “More if he wins, which he never has.”

Her bar tab was often more than that.

“Don’t do no math.” She indulged bad grammar for effect. She celebrated the fraudulent in her character and body, fluttering false eyelashes, adjusting her enhanced bosom, tilting her head to display the bleached teeth behind the painted mouth.

Melinda joined them, unloading a tray of dirty glasses. “Can there really be a demolition derby every Friday night?”

“In the summers,” Kay said, “but he has to go all over. One time way down to Texas. Lender? Lander? Leander?”

Melinda wore the shortest skirts of any waitress. The men in All Nite studied her hungrily. From the first hour of her first shift Paul had the feeling they would wind up in bed together. How it happened: she bumped the garbage bin over and balked at the mess, an expression of horror on her face. Paul cleaned it up. Certain objectionable chores didn’t bother him. It was like changing a child’s diaper, he explained, not distasteful but satisfying. She responded by going home with him. She hadn’t seemed to enjoy the sex but kept offering and they did it a second time, standing in the Airstream after breakfast, her elbows on the counter. He remembered thinking that she’d cast a longing look at her crossword. “Why do you have the tattoo of a rectangle?” he had asked, pausing but still engaged in the act, his face in her hair, unable to finish and unwilling yet to admit it.

“It’s Colorado,” she said, “my home state.”

“You’re from Ohio.”

“It’s a book, then.”

“It’s not a book.”

“It might be a book. I read.”

“Looks more like a television.”

“All right, then,” she’d said. “Are we done?”

All Nite was housed in the oldest surviving building in town — the original mercantile, where Paul’s grandfather had heard the story of Aesa Fett, and which Paul’s father would later manage and eventually sell. It became a department store, the Modern, a place Paul recalled from his youth. When downtown was vacated for the mall on the highway, The Modern was supplanted by a storefront church — the Holy Committee of Righteous Christ — whose floppy-haired minister plastered flyers of his face all over town, declaring himself god’s delivery system. He played electric flute and drum machine during hymns. Paul met him once, in a bar on the north end of the lake. “You recognize me, don’t you?” the preacher asked as he slid a creased five into the tight filament of a stripper’s thong. “You’ve seen my posters,” he insisted. Paul merely shrugged, but they shared a table, a pitcher of Pabst. “I am of the flesh,” he said. “I’ve known fire and I’ve known rain.” A few months later the doors to Righteous Christ were chained shut and the building mutated once more, becoming All Nite. Paul had tended bar for two years.

“Einstein,” Kay said, “your hand’s heavy as an anvil.” She lifted her drink approvingly, ice cubes making their secret shapes beneath the hiss and spit of tonic. “One of these nights, you’re gone drown me in happiness.”

He had the same feeling about Kay Timmons that he’d had with Melinda — some Friday night while her husband was out in Leander colliding with passing Corollas, Paul would take her home. Ever since the fire, women sought him out.

Colman and Aesa’s first children — boys, two years apart — died in 1929, during the influenza epidemic. The next child they kept home. He never attended any school, spindly Sean, the slightest of boys, who learned to read on his mother’s lap from the only books in the house: The Real Charlotte, Gulliver’s Travels, the King James Bible.

A fourth child was born in 1931, when Aesa was twenty-seven and Colman was seventy-four. The girl was never christened, surviving a matter of hours and taking her mother with her when she departed, the spread of blood so severe that the mattress could not be redeemed. Colman constructed a crude raft the size of the ruined mattress, which he saturated with kerosene before arranging on it the bodies of his wife and infant daughter. In his best clothes, he strode into the water. Waist-deep he studied their repose. Finally, in darkness, he lit a match and pushed the raft, let it drift into the deep.

Frail, bewildered Sean watched from the house, behind the transparent pane his father had set in the wall at an angle: his father in the water, his mother and the other on the mattress, the drifting flame on the lake. For hours he watched. When his father came inside, there was ash in his hair.

Sean was seven when his mother died. His father tacked a notice on the wall of the mercantile for a woman to raise the boy, and he hired the only applicant, a young widow named Etna Toft, whose husband had died in the construction of the Gilboa Dam. She met Colman at the mercantile, Sunday shoes on the plank floor, a stiff gray dress, hands demurely at her waist, a hint of a smile on her lean, homely, intelligent face. Colman merely nodded his approval. He nailed shut the door to the room he had kept with his wife, which meant that Etna Toft shared the other bedroom with little Sean.

For the remaining fourteen years of his life, Colman slept downstairs, on a blanket spread over the hardwood floor. He quit shaving or cutting his hair. He gave up speech. But he continued to rule the house and his business, conceding nothing to men who thought to take advantage of his silence. He carried a polished walking stick that he was not loath to swing and remained strong to the end, forceful to his final day. Only occasionally did he lose himself: oaring into Bony but forgetting the line, the bait, the rod, his hat and coat, gone until evening, returning sunburned and without shoes, his shirtsleeves damp; boiling water on the wood stove, depositing tree bark, segmented gourd vines, winged insects culled from the rotting trunks of fallen fir into the pot; mistaking Etna Toft for his dead wife, pulling her into his arms, his hands clutching her ribs, his mouth murmuring at her ear.

His son was taught to ignore the embraces. “Let him have his reunions with the dead,” Etna advised.

“He speaks to you,” Sean said.

“Not to me.”

At the age of twelve Sean left the upstairs room to make a bed beside his father on the plank floor, and at seventeen, he reported to Naval Station Great Lakes. He served in the Pacific on the U.S.S. Long. When it sank in January of 1945, he was pulled unharmed from the water by a rescue ship, the U.S.S. Hovey. The following day, a burning plane crashed onto the deck of the Hovey at the same moment a torpedo struck the hull. Sean found himself once more in the blazing waves, and he was saved again, this time by the U.S.S. West Virginia. Bones in his legs and ribcage were shattered, and a shard of searing metal left him blind in one eye. He was sent home, where he discovered that his father had disappeared.

According to Etna Toft, Colman went out onto the frozen lake with his hand auger and rod and never returned. A local boy, who had also been ice fishing, claimed to have seen Colman’s body, floating faceup, arms spread, hands pressed against the underside of the frozen lake like a child discovering the Christmas display window at the Modern. A crew of men with axes searched the ice, but the body was never found.

The day Paul first spoke to the woman who would become his wife, after he had swiped his roommate’s pickup, loaded her every possession in the truck’s bed, and driven away from the sarcasm of her boyfriend, she had begun singing to herself: O Lord, won’t you buy me a Mercedes-Benz? He never called her anything but Benz.

They tried the houses of her friends, but none would take her in — the first was not home, the second claimed her boyfriend wouldn’t like it, the third said her boyfriend was too enthusiastic. In the end, she agreed to stay with Paul.

“Just till I can find a place,” she told him, “and I’m not going to screw you.”

“I know.”

“Or cook or something.”

“I have zero expectations,” he said. “Except I’ve seen you around and I’ve wanted to get to know you. Ever since I saw you watering plants with a coffee can.”

“My plants!”

“We can go back at midnight and dig them up.”

“I packed the coffee can.”

Within a few weeks they were lovers. She simply stepped into his bedroom one night, saying, “That couch is so uncomfortable,” and pulled off her blouse. On a winter’s night a few months later, she said, “If you could only cook, I’d marry you.” He enrolled in Mediterranean Cuisine for Beginners, and they were wed before it met.

It was not her first marriage, but she didn’t like to talk about her ex. Paul knew only a few things about him. He ate fat-free lemon cookies. Paul had selected the cookies in the grocery, and Benz said, “Don’t get those. Manny ate them.” Manny wore flip-flops, Paul knew, because she threw away Paul’s flip-flops. Manny liked football, shaved his head, suffered cravings for sweets, and didn’t want children. “Knock me up,” she said one warm day when the lake was shushing against the dock. “Sow a seed. Plant a little soldier in the incubator. Let’s take our lives seriously.” This was after his parents drowned and left him the house on the lake. The place was theirs, free and clear. They felt rich. Anything was possible, even the future.

And after sex, while they lay in the afternoon sun, the French doors open on the water, she said, “Are you going to be weird about the lake?”

He was asleep and she had to repeat the question. His parents had rowed out one evening and never come back. Bony Lake spanned two hundred feet from surface to bottom and was murky in its depths, down where Paul’s relatives dwelled. But his parents’ deaths were different from the others. They had chosen to die. Lymphatic cancer was killing his mother, and his father had an increasing number of days when he could not claim his own name. Paul said, “I’ll be weird, no doubt, but not about them.”

“Manny hated water. It scared him.”

Paul smelled fear at that moment. It smelled like the lake. “Are you still in love with Manny?”

“I guess,” she said, “but I’d rather be with you. You’re my husband.”

“Not the perfect answer,” he told her, but he was buoyed, nonetheless, by some great, nameless emotion. “Husband and wife,” he said. “A house on the lake. Maybe a bun in the oven.”

She put her hands on her abdomen. “I’m pretty sure we did it. I feel occupied.”

Despite his war injuries, when Sean Sheelin Iris took possession of the house on Bony Lake, he was industrious. With the help of Etna Toft, he pried open the door his father had sealed, discovering his mother’s clothes hanging in the armoire, tears in the fabric from its own gravity. He and Etna emptied the room. He painted the house, installed electrical wiring and indoor plumbing. He converted the pantry off the kitchen into a bathroom. He knocked over the outhouse and filled in the wretched maw. He revived his father’s business, and during his third year home from the Pacific, he proposed marriage to Berit Thoresen, the granddaughter of the mercantile’s founder, who counted the eggs, kept the ledger, and weighed the walleye. Her brown hair reached her waist, and one of her legs was shorter than the other. “If I can still work behind the counter,” she replied to his question.

He carved out a second bathroom in the old house, on the upper floor, to spare his bride trips on the stairs. A year later, he insulated the roof and redesigned the ground floor, adding a bedroom and the French doors. After ten years of a happy but childless marriage, Berit, one summer afternoon, had her lunch on the dock and slipped into the water for a swim. Her body was discovered on the far side of the lake, among the roots of the giant birches. Fish were found in her hair.

Sean left the house, claiming an apartment above the store he now ran, visiting Bony Lake and Etna Toft infrequently. He would not marry again until 1983, shortly before he turned fifty-nine, and this wife, whose name was Anna Montgomery and who was thirty-eight on their wedding night, gave birth to Paul Montgomery Iris later that year.

Sean reclaimed the lake house, and over the years he added a garage, a gravel driveway, an automatic opener for the wooden gate, wall-to-wall carpeting, a satellite dish. Paul Iris was raised in the house. He would leave for college and come back without a degree but in possession of a wife, for whom his parents would immediately tumble. They would continue to love her until their deaths in the first decade of the new century. Paul was twenty-six when the house became his, and within a year it had burned down to its white oak joists.

Smoking in bed. Drunk and smoking in bed. He had scars on his thigh, a battleground of skin seized from other parts of his body, stitched into place by a surgeon from Hyderabad, India, who advised him to sell the property and move away. “Too many people here are like Hannibal’s elephants,” he said. “They never forget one damn thing.”

The third time Melinda spent the night, she found Paul’s stash in the cupboard beneath the range. She had been talking about her father and looking for steak knives.

“He has a theory about memory,” she said. “He’s got this boss he instinctively dislikes, only what are instincts in humans but leftover memory? And one afternoon we’re watching cable, old shows he watched as a kid, and on this episode of Combat! there’s an actor who actually does look like my dad’s boss, and he’s a German spy. Voilà! From that point on, we watch nothing but black-and-white TV — Dobie Gillis, Beaver, Outer Limits. He’d spill these facts about the cast, like Vic Morrow, who was Chip Saunders, got sliced in two on the Twilight Zone set by a helicopter, and Dwayne Hickman, who was Dobie Gillis, could never get roles playing adults. Every one of those actors had tragic lives, my dad says, but back when — Are these pictures?” She had found his stash in a low cupboard.

“Put them back, please.”

“But why are they like this?”

Each photograph was wrapped in tinfoil.

“I don’t want to look at them,” he explained.

“Do you want me to throw them away for you?”

“I don’t want you to look at them.”

“I wouldn’t —”

“Yes, you would. Besides, I don’t want to throw them away.”

She held a stack in each hand, as if she were about to shuffle them. “I’ll put them back.” She was naked. She claimed there was no point in getting dressed if you lived in a trailer the size of a sneeze.

“Do you enjoy sex with me?” he asked.

“If it makes you happy.”

“But do you enjoy it? Enjoy doing it?”

She turned her head sideways. “Girls are like that.”

“I want you to have an orgasm. I can’t do this unless you have an orgasm at least some of the time.”

“You don’t always have one, either. Not very often, really.”

“Lie down.”

“What are you going to do?”

“You’re going to have an orgasm.”

The lozenge against her teeth expressed a sentiment neither could articulate. After a moment, she added, “I’m not sure I like your attitude.” Her words were muted and slow, with long pauses, like a person speaking underwater.

“Forget it, then.”

“Don’t get sulky.”

“Read your book, do your crossword, tell me again about Lassie or Lost in Space, how George Reeves died in his bedroom.”

“I’m happy to do it.”

“Can you at least say fuck?”

“It doesn’t take half a brain to say it.”

“Say it then.”

“We can fuck if you want to.”

“No, thanks.”

It had been wilderness when his grandfather built there. Bears fished in the shallows, and the odors of the wild entered the house and stayed. Up to the end Paul would catch a whiff in a little-used closet or cupboard. His grandfather had shot a bear and kept its hide, sleeping beneath it the final years of his life. His father domesticated the yard, planting grass, mulching it in the spring. The grass came back after the fire, and Paul kept it mowed. His trailer was fifty years old, the faded silver of old dimes, curved like a sperm, parked right where the house used to be.

“A lake is good for reading,” Melinda said. “Sit beside water and you concentrate. It’s like you’re doing more than if you’re reading in bed.”

Concealed in lawn chairs on the dock, they drank cold beer. Melinda read. Paul analyzed her: intelligent, crafty, big-spirited, small-minded, wise. The lake this day was the color of ash, as was the sky.

“You should try a book every now and then,” she said. “You want this one?” She offered her paperback, red-spined like a fish.

“What’s it about?”

“People making a mess of things. But it’s different in a book.”

“If you have a crossword, I’ll do that with you.”

She lifted her bag and searched. A leathery odor rose from the purse’s wide mouth. She unwrapped a candy and deposited it on her tongue before speaking. “I’m not sure what you’re doing with me.”

“Here we go,” he said, “the requisite conversation.”

She found the crossword book and let the purse clatter to the deck. “It’s not what you’re thinking.” Like a boat tapping against a pier, that lozenge against her teeth. “I’m not in love with you, Paul Iris.”

“It’s just a pity-fuck kind of thing?”

“More like science.”

“Why is it since the fire women go out of their way to be with me?”

“They want to heal you.”

“Lots of people need healing.”

“Not too many burned up his wife and child.”

He tossed his beer bottle end over end into the lake. It splashed and then it splashed again. Birds flying overhead made their noises. Finally, he said, “We had the doors open to catch the breeze off the lake.”

“Oh,” Melinda said and put down the crossword.

“I kicked off the bedspread. Kicked it off me. We’d been having a little trouble. Something we would’ve gotten past, but my hand, the hand with the cigarette, dropped to my side. The bedspread might as well’ve been made of gasoline. The draft pulled the flames into the hall and through the house. Pulled them away from me. I’ve just got this scar —”

“The combat zone,” she said. “I’ve seen it.” Then she added, “You’re broken. That’s why women are attracted. You’re a broken man who has lost everything. You’re irresistible.”

“The baby’s room didn’t burn. Just the smoke. Her skin was so gray, almost . . . My father put French doors in the master bedroom. When you opened them, it was like the lake slid a little ways into the room. The stars in the water would shine in the house.”

“Everybody has the urge to burn down his life, but you did it.”

“Is that why you’re here? To burn your life down?”

“It’s not like that.” After a few moments, she said, “Honest, it’s not.” Then, “I need a Civil War general, seven letters.”

“Lee and Grant,” he said. “Those are all I know.”

“You could build your own house out here.”

“What’s wrong with the trailer?”

“It’s so teeny it’s like being swallowed.”

“You want to be with me because I killed my wife and daughter?”

“I see this potential in you. I’m not thinking husband, I just want you on your feet again. I mean, truth be told, we’re not even friends.”

“Sherman. General Sherman.”

“I knew that one,” she said. “I wrote it in while we were talking.”

“After you die,” Benz told him, “you’re like a kid in church who wants to get outside but there’s no outside, and the world is pouring through you but you’re not in it.” Her hair held light and smelled of pine.

“How is it, then, that you’ve come to me tonight?” he asked.

“ ’Cause you’re so fucked up they gave me a pass.” Her exhale lifted her bangs, which were luminescent, feathery, unreal.

“And our daughter?”

“I’ve seen her, but you don’t hang with people. It’s more impersonal than you’re thinking.” She turned her head like a deer — sudden, alert, uncomprehending. The ear visible to him curled charmingly against her head, a fetal curl, the skin pink with thought. “It’s more like you witness, only that’s not the right word either.”

“You don’t sound like yourself. I think I’m dreaming.”

“This is no dream. I can prove it.” Her hands made a church, here’s the steeple. “ ’Member that time we were in the tunnel? The ambulance came thundering? Flew past so close we could feel its breath?”

“I remember,” he said, “though that never happened.”

“This is a dream?”

“Looks like it.”

“Don’t wake up yet.” Her features slipped into the real, the actual, the precise woman Paul loved, her imperfect skin and complicated eyes coiled like caterpillars. Even her breath tasted of her. “Why don’t you tell people you were no good at smoking?” she asked.

“I was mad at you, though. What if, because I was mad . . .”

“Don’t dwell.” She shook her head, her hair a magician’s cape. “And you know, if you wait till you’ve got to pee before you screw, you might have better luck coming.”

“Okay,” he said. “Noted.”

“All I’ve got to offer, except I like the net you use when the fish are frying.”

He made a grab for her, but she slipped through his hands. It was dawn. A smell in the trailer like cut hay and sugar. Melinda’s ghostly skin and the book against her bare chest, book light shining on her sleeping face, shadows flitting across it like expressions.

“I was angry and drunk, and I was going to show you,” he said softly, as if he were still in the dream.

The sleeping woman beside him did not wake and the lake remained still, unmoved and unmoving, patient and present — reliably present, horribly present.

The Iris men had a long history of competence. It was mysterious to Paul that he was the only one left and yet he was utterly inept. There had to have been bungling in generations past. His father had dented a car by backing into a concrete post, Paul recalled, and he’d held on to the mercantile too long. And his grandfather, one way or another, let all his children but one die. His great-grandfather had come to the United States from County Cork, and the immigration forms confused him, leading to the name Iris, which was meant to be Irish in the box asking for nationality. By all rights, they were the Sheelins from the Blackwater Valley. Incompetence had made them Irises, as if they were flowers or parts of the eye, and after 120 years, Paul and the Airstream, the charred ground, the deep water, and that insurmountable wall — such was all they had to show.

Paul had once fixed a hanging lamp that would not stay lit by lashing a book to the pull string. And that last night he had bumped into the perimeter wall, driven the Colt up to the gate, and while he fumbled with the automatic opener, the car banged into the wall. Benz made her way out to the car and gestured for him to slide over. They had fought earlier, words hurled like spears, but she maneuvered the Colt inside and up the gravel drive for him. She shut the gate and left him in the front seat. He stayed there a long while. If he’d had cigarettes, he might have spent the night in the Colt. In the morning, he would have held his daughter and told his wife he was sorry. They would have made love with the doors open to the lake. It would have lapped at their bed and reflected sunlight on their skin. But he was out of Luckies and made his way inside.

Melinda came over only on weekends, usually in the afternoon when he was raking leaves, sharpening the blade on the lawnmower, or running a tiller through the scorched ground, which held the char the way water held light — three years since the fire, but the ground was still black just beneath the surface.

He would not go to Melinda when she arrived. He would not call out to her. They did not embrace. She would make no effort to help him in his chores, plopping down in a deck chair, her tiny feet and slim white ankles visible beneath the hem of her black pants.

Sometimes she began a story. “There was this one Have Gun, Will Travel my dad really hated . . .” she might say. Or she’d have her pinkie marking the page in a book, parts of which she would read aloud, as if a passage had to be heard to be understood. Now and again she came with a proposal in mind — a walk along the shore, a drive to watch the leaves change, or what was the purpose of pulling a boat out of the water to scour if you never went rowing? The boat was the same one that his parents had taken into the twilight, iris stamped onto a brass plate on the bow. They never did any of the things Melinda suggested, though once they cast lines into the lake, and he caught a lake trout, which he threw back, and then she caught the same fish, Paul’s snipped line hanging from its mouth.

“This is a really stupid fish,” Melinda said.

“Or really hungry. Mortally hungry.” Paul gutted it, fried it in butter. They ate with their fingers on paper plates.

Mostly, they fucked, the aluminum trailer squealing and whinnying along with them. Paul could rarely reach orgasm, needing to pee or not, the sensitivity there and gone, images of Benz and the places where they had made love flitting through his head, pleasurably one moment and disastrously the next.

A person from his past, from his youth, a slim white-haired woman with sun-damaged skin, had come by shortly after the fire, the same day Paul paid a man fifty dollars to tow the Airstream across town and park it at the edge of the lake. The woman, whom he recognized but could not name, had brought a fish casserole. “He used to take the horses into the lake,” she told him. “Horses can swim, a high-stepping kind of swim. They punch the water the way you do dough to stop it rising.” She made an incomplete gesture with her hand. “You recall wiggle-tails in the cistern?” When Paul did not answer, she added, “He went down there searching in the night, by moonlight, all along the lake, but he never got to that stand of birches. I’ll want that dish back.”

After she was gone, Paul dug his fingers in the casserole and scooped it into the lake. He set the rectangular Pyrex dish, which was burned black on the bottom, on the surface, to see whether the dark water would float it. The dish drifted only a moment, a badly designed ship that would make its way to the bottom of the lake, which held all that remained of Paul’s kin. A family mislaid. All but him.

It was only later that night, his first on the trailer’s narrow mattress, that he realized the woman was Etna Toft, who had lived in the house while he was growing up, who would have to be more than a hundred years old. How could she have gotten to the lake from the nursing home? He switched on the light over the bathroom sink to check his fingernails, but he could find no residue of the casserole. His fingers smelled of soap. When had he last visited her? But no, she had been dead for years. She had died before the fire, complications from the flu, her lungs filling with fluid. Another drowning.

Paul and Melinda stayed out until morning on the dock while the wind skimmed their bare bodies and brought sounds from the other side of the lake: the cry of a car door opening on a bad hinge, the intermittent music of some lousy rock song, and television, of course, the language of men and women from old movies playing in the small hours, voices of the dead bouncing off the water, mixing with the other sounds, and, when the wind shifted, all of it disappearing.

The lake smelled of fish and dampness, which meant the smell of char was temporarily overcome. He stood to piss over the side of the dock and then dived into the dark water, which was cold any time of year, and he swam down and down and down, the lake not shallow even here, until his hands touched the soft bottom, which he patted, as if searching for something — the casserole dish, perhaps — but what he touched, what he thought he touched, was his mother’s face, not eviscerated by water and the powers of nature, but the pliant skin and smiling face of his mother. He remembered as a boy pretending to be blind, imagining his mother’s expression by patting the features, and he realized that it was not his mother’s face but his wife’s, which made no sense, as she had not drowned. He swung his legs around and frogged off the bottom, his lungs aching by the time he reached the surface and pulled in the fragrant air. Melinda, who had followed him into the lake, dog-paddled beside him in the dark while he spat out lake water.

“You were gone a long time down there,” she said.

What did he know about her, really? She preferred gin but drank vodka, which was supposed to be easier on the body, less likely to chisel the drinker’s lines in the face, and she treasured her ordinary face, her chunky, adorable body, and maybe that was what made it desirable, Paul reasoned, the loving way she presented it, even to the customers at All Nite, the careful way she walked with trays of sparkling drinks.

He touched her wet hair as they made their way to the dock, he touched the blue rectangle on her shoulder, deciding that he would not dive into the lake alone. He did not want to kill himself, and if he did kill himself, he did not want to drown in the lake as the others had, or burn beyond recognition as his wife had, or suffocate from smoke as their child had, whose name had been Elizabeth and whom they called Baby and who, from her crib, had stared right at Paul, as if she understood that he was someone important in her life, that this man was her father — or maybe it was something else she understood: This was the one who would kill her.

No, he decided, kicking to keep his head above water, he would take pills, a different kind of drowning, a slow and easy sinking, like the broad oak leaves when they fall from their limbs, rocking to earth, touching gently down.

With a sour dish towel over one shoulder, his left hand on the polished wood of the All Nite bar, he asked Melinda to dinner. They’d never eaten together outside his trailer.

Melinda had her fingers in several glasses as she declined the invitation. “It might give us both the wrong idea.”

“The idea is I want to take you home with me, but first I want to eat.”

“Pick me up after.”

They didn’t fight. They never fought. They’d had a few dull arguments but never had a fight. When they got to his trailer, he opened cans of Hearty Man. “How about after we eat,” he said, “we go for a drive?”

She agreed to go as long as he promised not to stop the car.

“What if we need gas?”

“Do you need gas?”

“No.”

“Okay, then.”

He filled a thermos with chilled, transparent liquor and took the narrow asphalt lane that followed Bony’s shore. The moon in the lake was a wobbly biscuit of silver light.

“I used to be a risk taker,” she said. “You know how when the dark is out there, and maybe you give yourself permission to let it take the wheel — that was me back when. Not now. Even this, drinking martinis on this nowhere road, I wouldn’t do if I were driving.”

The Colt wound through the woods, into the hills, and he slowed, cut off the headlamps. They could see nothing, but he sensed the pines and juniper, the briars, the black earth rich with worms, and they heard the rush of a stream that fed the lake, and through the open window of the car, he smelled the water and the dirt and the million stars. The stars smelled like salt.

She put her feet in his lap and let her hair fly out the window. The wind through the open windows inflated her skirt.

She said, “I’m glad I met you, even though . . .”

“What is it that you really want from me?” he asked. It was too dark to see her face, just her ashen legs, the mumbling movement of her skirt, moonlight in her martini. “What do you want from this relationship? If it is a relationship.”

“Just exactly what I’m getting.”

“What about from life, then? What do you want from life?”

“I used to have this dream,” she said. “I’m on a diving board wearing a gold gown, and the wind is making it flutter. It’s nighttime, and there are people with guitars and horns and steel drums surrounding the pool, but they aren’t playing any music, and when the gold from my dress passes over them — or through them — I hear what they’re thinking, which is overlapping and mixed-up, all these different voices, and they’re all thinking about me. Some are wondering whether I’m going to jump in and some wonder whether I’ll let the whole dress fly off and some want me to fail — though it’s not clear what I’d be failing at. On the other side of the pool, there’s a man with a whistle, and he points at the musicians and they start playing a bunch of different songs at once, and I understand it’s time for me to take the leap.

“There are hooks and straps and buttons on the dress that I unhook and slip the straps off of and unbutton, and I sense the impatience of all those people, and then my feet slip and I’m falling and the gold dress flies off me, floating away, way up above me, and the musicians disappear, and there is another level of people beneath them, like a parking garage, and they’re in formal clothing and drinking out of crystal glasses and my parents are there and I call out to them but they’re already gone, and there’s another level full of people in cheap clothes, the men’s shirts so thin that you can see through them, and a level below that one with old-fashioned people dancing. There’s no end to the levels. I’ve had this dream maybe four times, and it’s the most special thing in my life.”

“All right,” he said evenly, said quietly, said firmly, “quite a dream. Really quite a wild dream. But that wasn’t my question.”

“Turn the headlights on now.”

“What do you want from life? That was the question.”

“The dark is making me nervous.”

“Answer the question and I’ll turn them on.”

“What I want is to not make a mistake. To not make a mistake I can’t correct.”

In the sudden tunnel of artificial light: deer stood on the road only a few yards ahead. They raised their heads. They hoofed the air. Gone.

“We would’ve hit them,” Melinda said, filling his glass from the chilled thermos. “One more minute in the dark, and we would’ve hit them.”

On the drive back, he recalled the last words Benz ever spoke to him: “Just don’t wake Baby when you come in. That’s all I ask of you.”

“Would you call that unbridled passion,” Melinda asked, “or bridled?” Her cheek held a crease from the wood paneling. They had just given up on an unsuccessful trot through multiple erotic positions.

“I don’t know what’s going on with me,” Paul said.

“Oh, it was okay enough.” She pulled a pen and a pocket calendar from her purse. “Honest, it was.” Her sweet, rippling laughter sounded like the contortions of a shallow stream. “I’m all come out, come out, wherever you are but you’re still bent on cover.” She tapped the ballpoint against September. “Let’s pick a day to break up. I know the anniversary of the fire is next week, but what about Tuesday of the week after? Should we wait two weeks after?”

“Why do you want to break up?”

“It’s called managing your future,” she said. “Most people can’t do it, but I can.”

“What’s the point of it?”

“The point is, I wanted to do this but I didn’t want it to become anything more than what I planned. I aimed for A-B-C-D and the problem is, you blink and you’re at Q-R-S-T and you feel committed.”

“We’ve hit D, you’re saying?”

“It’s a good quitting point.”

“Then what?”

“I’ll pick someone else.”

“What’ll I do?”

“Mope and drink and screw some other girls. Hole up in this little pony keg like you’re waiting for doomsday.”

“Don’t you wonder what Q-R-S-T are like?”

“They’re filled with squalling children and bills for refrigerator repair and wearing the same shoes for two years and putting vinegar in the kitchen sponge and running it through the microwave to get rid of the mold smell and save a few cents on a new sponge.”

“All right then. Tuesday’s fine.”

“December breakups are ideal,” she acknowledged, making an X in the box, “but it’s too far away.”

And then it was October and a brisk wind crossed Bony Lake to make the Airstream flinch and tremble. The deadline had come and gone but Melinda was still in his slender bed, her autumn feet no colder and no warmer than her summer feet.

“It can’t be Flicka,” she said, erasing. She had a themed crossword puzzle, page three in a book her father had sent her. “It has to end in ‘r.’ Forty-seven down has got to be Lone Ranger. I know that’s right. I know everything about the Lone Ranger.”

“Who was his wonder horse?”

“Hi ho Silver,” she said, scribbling as she spoke. “You’re good at this.”

“I didn’t get it, you got it.”

“My dad complained about the bad plots, but we still had to watch it. All the real people met terrible ends — the Lone Ranger, Tonto, even Silver.”

“Why don’t they show Westerns anymore,” Paul asked, “instead of the crap they have on now?”

“Like you even own a TV,” she said. “The guy who played Tonto never got any parts but Indian stereotypes, and the guy who played the Lone Ranger kept wearing the mask after the show was canceled, like to the dry cleaners or dentist, and when they tried to make him stop, he wore dark glasses that looked like the mask.”

“You’re happy now, aren’t you,” he asked her, “that you didn’t leave me?”

“I’m all right with it, yes,” she said, putting the book down. “Only I’ll still have to, and it’s going to be harder.”

“Why worry about that?”

“Because it’s going to be really hard.” She got up to dress. “It isn’t me that you’re going to be okay with,” she told him, buttoning her blouse. “And it’s not the next one after me either.”

“The next what? The next woman?”

She pulled up the All Nite skirt, tucked in the All Nite blouse. “It’ll take a whole string of us,” she said. “What’s the point of not leaving?”

He remembered holding Baby in his arms and smelling her breath, which smelled like nothing, which smelled like the lake when the lake smelled like nothing.

“Don’t get that look on your face,” she said. “It’s not fair if you get that look on your face.”

“You just said you were glad you didn’t leave.”

“Even if I’m glad, sooner or later I have to. If I don’t, I’ll be dragged to the bottom, too.”

He caught her at the door, physically caught her, his arms around her waist. “You can’t go, you didn’t finish the crossword. You left your pen. You never told me what happened to Silver.”

She tossed the puzzle book onto the stove. “You finish it. And keep the pen. Going-away gift.” He didn’t let go, even when she bent forward and pushed the door open to let in the lake. “There was a fire on the production lot,” she told him. “They got all the horses out in time, but they didn’t hold onto them. Somebody has to keep hold of the reins or they’ll run right back in.”

“That’s what happened?” His arms fell away. “Is that what you’re saying?”

“Does it matter what I’m saying?” She jumped down, landing in the disturbed earth, stumbling before righting herself, her blouse catching the light, just the blouse, and then it, too, disappeared in the dark.

A few minutes later, he put his fist through a closet door and drove himself to the emergency room for stitches.

The wind has died. The night is surprisingly mild. He finishes off a bottle of rye and unwraps the bandage. His good hand manages the doorknob. It is three a.m. He stumbles onto the dock, kicking off his shoes, one skipping across the planks and into the water. He has to sit to pull off his pants one-handed and then forgets to remove his shirt. The water is not as cold as he imagined, yet a chill takes his legs, his chest, his arms. He swims, the stars his only witness, speckling the lake with bright indifferent eyes. He swims in the direction of the birches. He has swum it before — sober and in summer, in daylight, when he was eighteen and somebody’s son, somebody’s classmate, somebody’s boyfriend. He didn’t expect to swim it this October night. Why didn’t he take off his shirt? What are the names of those horses his grandfather lashed to the auger? Why was the old man’s body never found? His mother used to read to him at bedtime. His father taught him the names of the gods. The horses swam in this lake, spotted horses, hooves agitating the deep. His wife, one night, standing over the bassinet, said, “Babies have more bones than humans.” Adults, she meant. Babies have more bones than adults. “They fuse together as you grow.” He swims the bitter water, the cold radiating from the depths of the lake. “In the war,” his father says, “a man learns to . . . a man learns to . . .” What does a man ever learn? Paul wonders and swallows lake water. He lifts his head and doubles his effort, the white trunks of birches appearing in his mind like columns of cream. They possess a divine stillness, those trees, starlight making their limbs glisten. They shine with an unsteady clarity, like a luminous stand of unreasoning thoughts.

Here are the clues, say the birches. What is the mystery?

As he swims, his bones leave him. There are fewer with each stroke, until he is a single thing, a human raft, a thrashing object on the surface of Bony Lake, and then not on the surface, and spitting water, submerged, redefined, a sinking man, and then . . . his feet touch the muddy bottom and they instinctively push off. His head crowns and he breathes in the night air, flounders ahead, until he understands that he can stand, that he has reached the other side. He plods forward and crawls to the base of the birch trees, which are not so white or so grand as he imagined them. He collapses among their roots, rejected by the lake that has always solved his family’s problems.

“Who are you?” asks a voice, a woman’s voice.

It is morning and he has been found.