It’s possible that Michael Dukakis didn’t understand the question.

“If Kitty Dukakis were raped and murdered,” CNN anchor Bernard Shaw asked the Democratic candidate on live national television near the start of the second 1988 presidential debate, “would you favor an irrevocable death penalty for the killer?”

What Dukakis could not have known at the time, amid the lights and the electric hum, was that the whole doomed history of the American left had quite suddenly come to rest on his answer. His rote reply — “No, I don’t, Bernard . . . ” — marked the end of more than just Dukakis’s own career. The response seemed to confirm the suspicions at the heart of arguably the most devastating attack ad in presidential-campaign history: George H. W. Bush’s Willie Horton spot. The parable that emerged in 1988 — liberal politician goes soft on crime, black criminal goes on violent rampage, liberal politician loses election — quickly hardened into political truism. For Dukakis’s woebegone party, loser of three straight national elections, his strategic failure was what our current Democratic president might call a “teachable moment.”

Four years later, Bill Clinton, who was then the governor of Arkansas, pointedly flew home to Little Rock in the middle of his own presidential campaign to oversee the execution of a man named Ricky Ray Rector. There was no doubt that Rector was a killer. But he was also handicapped — lobotomized by his own botched suicide — and there were profound legal and moral questions about executing a man who possessed the awareness of a dim young child. The case had dragged on for more than a decade, and in Rector’s final days, Clinton heard pleas from various Democratic stalwarts, including one of the candidates from 1988, Jesse Jackson, to commute the sentence and simply leave the diminished man in jail for life. But Clinton did not budge. His fortitude suggested a new breed: a Democrat who was more intent on winning elections than upholding bygone virtues, and who was willing to make the necessary corrections. As president, Clinton followed through on this promise: his crime agenda, the New York Times wrote in 1996, gave him “conservative credentials and threatened the Republicans’ lock on law and order.”

In the late Eighties and early Nineties, violent crime was unrelenting. For rich and poor alike, life in America’s big cities was marred by unprecedented numbers of murders, rapes, assaults, and robberies. Crime was a top voter concern, and a sizable majority of Americans supported the death penalty. Given the realities of the day, some Democratic posturing was unavoidable. But Clinton and his party stuck to the hard line through the mid-Nineties, even after crime rates began their dramatic decline. The 1994 Violent Crime Control and Law Enforcement Act — authored by Joe Biden, then chairman of the Senate Judiciary Committee — was one of the broadest expansions of the criminal-justice system in national history. “One of my objectives, quite frankly,” Biden said, “is to lock Willie Horton up in jail.” The bill devoted nearly $10 billion to new prisons, instituted a federal “three strikes, you’re out” rule, and created sixty new capital crimes and more than half a dozen new mandatory minimum sentences.1 It imposed mandatory drug testing on parolees, ended Pell-grant eligibility for prisoners — and with it most inmate-education funding — and established the Community Oriented Policing Services (COPS) program, which by 1996 was funneling nearly $1.5 billion per year to police departments nationwide.

Today, the crime epidemic is a cultural relic, no less a throwback than The Bonfire of the Vanities, crack babies, and the Willie Horton ad itself. Fear of random violence lives on, but the reality is that violent-crime rates have dropped to levels not seen since the early Seventies. Some criminologists and politicians, Biden chief among them, argue that our newfound safety is the logical outcome of harsher laws and increased spending on law enforcement. But that point is debatable — at the state level there has been little correlation between crime reduction and changes in incarceration rates. Whether we credit society’s better behavior to the legacy of Clinton-era policies or to the spiritual evolution of the species, the paradigm has shifted dramatically. Today’s urgent social problems no longer center on criminals and the depravity of their crimes, but on police, courts, prisons, and the system’s routine abuses of power. We traded grim murder, rape, and assault statistics for asset forfeiture, police militarization, and mass incarceration.

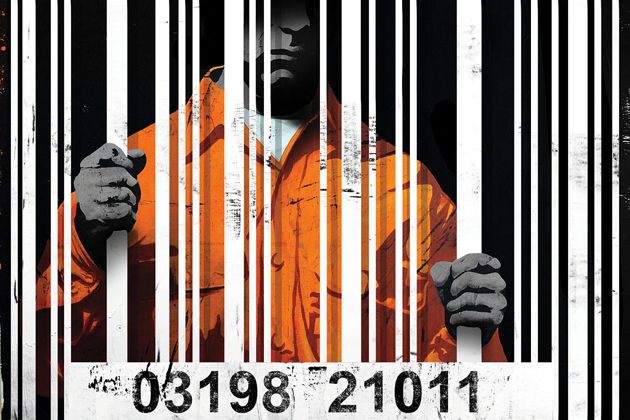

However often cited, the numbers bear repeating. The United States currently holds about 2.3 million men, women, and children inside secure concrete and metal boxes from which they will almost certainly not escape. Our nation is exceptional in this way, with incarceration rates that far surpass those in Russia, Iran, or any other country on earth. One in twenty-eight American children has a parent in jail. African Americans have for decades been arrested for narcotics at more than three times the rate of white Americans, despite using drugs at roughly the same rate. There are more black men in the prison system right now then there were male slaves in the antebellum South. Counting parolees and probationers, the corrections system controls the lives of nearly 7 million people. Half of all federal inmates are in prison for drug offenses, and post-9/11 immigration roundups have provided a new human-inventory stream. Between 2001 and 2011, the number of detainees held each year by Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) more than doubled — from 209,000 to at least 429,000 — making foreign migrants one of the largest demographics in federal custody.

The feeling that we overcorrected, that it isn’t the drugs or the crime but the efforts to defeat them that now cause the greatest social harm, is widely held across the political spectrum. It is repeated in a streaming harmony of newspaper columns, blog posts, radio shows, academic symposia, documentary films, and casual conversations. The shooting of Michael Brown, an unarmed teenager, by police officer Darren Wilson in Ferguson, Missouri, last summer and the months of civil unrest it sparked focused the country’s attention on the new dynamic. The militarization of our police and the institutionalized exploitation of black and poor people was suddenly crystallized in the image of small-town cops facing down their own community with sniper rifles and mine-resistant armored vehicles. In New York City, where violent-crime rates are approaching the lowest levels on record, an officer was caught on tape choking Eric Garner while attempting to arrest him for selling loose cigarettes. Garner, who died an hour later, can be heard on the recording saying, “I can’t breathe.” In the span of nine days, grand juries in St. Louis and Staten Island declined to indict the officers in both cases.

With the election of Barack Obama as the country’s first African-American president — and his appointment of Eric Holder, the first African-American attorney general — liberals might have expected a frank reappraisal of the policies that have devastated generations of minority Americans. Instead, they’re stuck with a party that still isn’t ready to get over Willie Horton. In the weeks after the grand-jury decisions, most prominent Democrats played it safe. Obama struck the necessary presidential notes, but he made no significant policy suggestions. This failure is particularly difficult to understand if one accepts the established story line: that the Democratic lurch to the right on criminal justice was driven by mere electoral expediency. It would be one thing — shameful in its own way, but at least explicable — if criminal-justice reform were too politically radical for the average voter. But the excesses of mass incarceration have become so apparent that there is little risk in speaking out against them. At the start of Obama’s second term, Holder stepped forward as one of the chief critics of the very system he oversaw. He made criminal-justice reform a signature cause and issued a stream of public critiques and Department of Justice memos that called on prosecutors to argue for shorter sentences and encouraged thousands of federal inmates convicted of nonviolent crimes to appeal for commutation. Holder’s words carried political freight, and news headlines heralded the dawn of a reformist era. But executive memos are non-binding. The drug war wages on, and the laws that put petty offenders in prison for twenty years remain unchanged.

As we enter the final quarter of the Obama presidency, neither the White House nor the Democratic Party has backed comprehensive reform.2 The party’s 2012 platform cited the ongoing need to “combat and prevent drug crime” and called for increased funding for the Byrne Justice Assistance Grant Program, a main source of funding for prosecuting drug crimes. It made no mention of criminal-justice reform. These facts raise a troubling question: if the New Democratic tough-on-crime attitude was entirely a matter of cynical, short-term tactics — merely the first and best Clintonian triangulation — why has it proved so difficult to undo? More to the point, how is it possible that libertarian conservatives like Kentucky senator Rand Paul have captured the moral high ground on the issue, while establishment Democrats seem content to hold the empty bag of a status quo that is not merely unjust but also, for a party that counts on the support of minority votes, politically untenable?

Last spring, I traveled to Washington, D.C., to seek out politicians of either party who would speak on the record about criminal-justice reform. Rand Paul was the highest-ranking official who wanted to talk. Paul has introduced five pieces of reform legislation in the Senate in the past two years, which addressed issues ranging from felon voting rights to civil asset forfeiture. He also signed on to three other bills, making him the only member of any party to attach his name to all eight. In his effort to make prison reform a Washington priority, Paul has rounded up an ideologically diverse coalition that includes several young conservative Republican lawmakers, all loosely affiliated with the Tea Party, and Cory Booker, the young Democratic senator from New Jersey. When he speaks about the issue, Paul often refers to Michelle Alexander’s book The New Jim Crow (2010), the bible of reformists on the left, which argues that racial disparities in the corrections system are a form of state-sanctioned oppression that follow directly from segregation and slavery.

“I think Eric Holder is sincerely for [reform],” Paul told me in an antechamber of his Senate office last year.3 “I’ve had lunch with him, and I think he sincerely does favor these bills. I think the president does as well.” But even the most popular reform measures remain stalled in the Senate’s purgatory. “The height of irony,” Paul said, “the epitome of what’s wrong with this place, is even when we agree, we can’t pass anything.”

Paul isn’t the first independently minded lawmaker to run into this roadblock. Jim Webb, a Democrat from Virginia — and now a member of this magazine’s board — devoted much of his single Senate term, which ended in 2013, to his National Criminal Justice Commission Act, which would have named a bipartisan commission to study the issue and make recommendations. The Obama White House never endorsed the bill, and in 2011 the N.C.J.C.A. failed to pass the Senate by three votes. Auditing the nation’s criminal-justice system, Republican Kay Bailey Hutchison said, was “not a priority in these tight-budget times.”

“Washington is dysfunctional, you may have heard,” Paul said with a grin. His conference room had the just-moved-in feel of a campaign office with more important things to worry about than décor. High on the wall, two oil-on-canvas portraits, one of Paul and one of his father, Ron Paul, the former Texas congressman, smile at each other. The paintings are unframed, too small for the wall they hang on. Each is unfinished, left by the artist with swatches of raw canvas showing through the places where the politicians’ jackets should be.

To the dismay of many Republicans and Democrats, Paul has spent a year leading the polls for the G.O.P. presidential nomination. Early in his rise, after he united liberals and libertarians with a thirteen-hour filibuster against the Obama Administration’s drone program, many Republican elders regarded him as a passing fad. But as the reality of his staying power set in, and after he announced the formation of what appears to be a serious fifty-state campaign, a neat symmetry emerged from Washington’s center. Democrats call him crazy, a creature from the right wing’s lunatic fringe, while hawkish Republicans use the reverse tactic, painting Paul as an impostor and a dangerous liberal mole. That strategy may prove effective, and on some issues, namely the re-reescalation of the war in Iraq, the attacks have caused Paul to vacillate. But on criminal justice he has remained consistent.

In picking up where Webb stalled, Paul has brought several conservatives along with him. “It’s not about whether or not we’re going to be tough on crime,” Utah senator Mike Lee told the Salt Lake Tribune. “It’s first and foremost about restoring justice to our justice system.” Idaho congressman Raúl Labrador, an unofficial leader of the rebel faction of House Republicans and a coauthor of the House’s version of the Smarter Sentencing Act — the more limited of the two mandatory-minimum reform bills introduced last year — frames the issue in terms of basic American values: “The Founding Fathers did not want states to have an easy job putting people in prison for a long time,” he told me.

These dissident Republicans have mounted an organized, three-pronged critique of the system’s failings: fiscal (prisons are too expensive), religious (criminals deserve forgiveness), and libertarian (the system is an authoritarian nightmare). Left–right coalitions have been passing criminal-justice reforms in red states for more than a decade, but Texas is the conservatives’ shining example. In the mid-Nineties, the state led the country in per capita incarceration, but in 2007, as Governor Rick Perry and the Republican-controlled statehouse were facing $2 billion in prison-construction and operating costs, they passed more than a dozen reforms that saved money and shrank prison rolls. The state shut down three juvenile-detention centers, cut the youth prison population by 53 percent, and allocated $241 million to alternative drug-treatment programs. Crime rates in Texas are at their lowest levels since 1968.

For Republicans in Washington, Texas offered more than an example of good policy; it offered political cover with conservatives. “If these ideas had been thought up in Vermont, they wouldn’t go anywhere,” Grover Norquist, the antitax activist, told me. Norquist helped found an informal Washington reform group that included David Keene, a former chairman of the American Conservative Union and later a president of the NRA; Edwin Meese, an attorney general under Ronald Reagan; and Pat Nolan, a former G.O.P. leader of the California State Assembly and the vice president of Prison Fellowship, the prison ministry founded by Nixon aide Chuck Colson after his Watergate-related incarceration. Republicans voting in lockstep may have defeated Webb’s bill, but Paul’s anti-establishment coterie sees an opportunity in the vacuum left by the Democratic Party’s passivity. “Our movement is showing that prisons, after all, are just another bureaucracy,” Nolan told me.

“Society is changing,” Paul said. “I think almost everybody, from Christian evangelicals to the far left, believe that people deserve a second chance and that putting people in jail for a decade for smoking pot or selling pot is not the appropriate penalty.”

The polls back him up, but polls don’t move legislation. Last month, Iowa Republican Chuck Grassley replaced the congressional reform movement’s most powerful ally, Vermont Democrat Patrick Leahy, as the chairman of the Senate Judiciary Committee. In a May speech on the Senate floor, Grassley opposed not only the content of the Smarter Sentencing Act but even the idea of bringing the bill to a vote. He described the act as “reckless, wholesale, and arbitrary” and called the fixed sentences prescribed by current law, which judges cannot overrule and which are widely seen as the greatest single driver of mass incarceration, “the only tool that Congress has to make sure that federal judges do not abuse their discretion in sentencing too leniently.” Another problem, according to Grassley: The reform bill “does not increase discretion for judges to be more punitive.”

Grassley has often found common cause in his effort to uphold mandatory minimums with Chuck Schumer, the New York senator who has long positioned himself as a tough-on-crime Democrat. Last year, the Senate version of the Smarter Sentencing Act was cosponsored by six Republicans, two independents, and twenty-three Democrats. Schumer was not among them. In 2012, Paul earned Schumer’s ire when he put a hold on a bill that created new twenty-year minimum sentences for purveyors of synthetic drugs. When Paul didn’t budge, Schumer’s office worked the press. “The grieving mother of a teenager who was killed after smoking synthetic marijuana is filled with fury at the lone U.S. senator blocking a ban on the dangerous drug,” the New York Daily News reported. “[Paul’s] got blood on his hands,” the Aurora, Illinois, woman told the tabloid. “It would be good to ask [Schumer] directly and get him on the record” about mandatory minimums, Paul told me. Schumer’s office did not respond to several invitations to discuss prison reform.

As I wandered the capital, speaking to a seemingly endless parade of reform-minded conservative Republicans and waiting for Democrats to return my calls, the senior senator from New York suggested a key to the mystery of why a political calculation that has outlived its electoral usefulness still drives Washington’s criminal-justice policy. Schumer is known around town for the money he raises from the financial sector and the political protection he offers Wall Street in return. Meanwhile, Rand Paul and his ilk represent the anti-corporatist wing of their party. Maybe the story of Democrats and prison reform is no longer the familiar one about pandering for votes, but an entirely different, if equally familiar, story about the unholy alliance of big government and big business.

A., AGED SIXTEEN, IN HER CELL AT THE HARRISON COUNTY YOUTH DETENTION CENTER, IN BILOXI, MISSISSIPPI. SINCE 2001 THE FACILITY HAS BEEN PRIVATELY OPERATED BY A COMPANY CALLED MISSISSIPPI SECURITY POLICE, WHICH RECEIVES OVER $1.6 MILLION FROM THE COUNTY EACH YEAR.

“I was looking for businesses that would be less volatile and that would perform better in a recession,” Tobey Sommer, a senior equity-research analyst with SunTrust Robinson Humphrey, a bank based in Atlanta, explained to me as the stock market boomed last spring. In 2009, the staffing firms that Sommer had been covering for SunTrust were reeling from the aftershocks of the financial crisis. “A lot of the stocks I covered were not stocks I would want to sell,” he said. His clients wanted the stability of what he calls “government companies,” and with partnership corrections — the industry term for private-sector incarceration — he found what he was looking for.

The profits generated by the corrections economy have not been definitively calculated, and a comprehensive audit would be a staggering accounting task. The figure would have to include the cost of private-prison real estate, mandatory drug testing, electronic monitoring anklets, prison-factory labor, prison-farm labor, prison-phone contracts, and the service fees charged to prisoners’ families when they wire money for supplies from the prison commissary. Contracted commercial activity flows in and out of every city jail, rural prison, suburban probation office, and immigration detention center. For stakeholders in the largest peacetime carceral apparatus in the history of the world, the opportunities for profit add up. For analysts like Sommer, the system also offers a safe, government-secured investment.

Sommer told me that despite the calls for reform and recent reductions in prison populations, the industry shows no signs of contraction. In fact, the majority of new prisons built in the United States in the past five years have been for-profit enterprises. Prisons are not the only corrections businesses that are flourishing, but they are the standard-bearers of innovation in the industry. Their business model is a simple exchange of money for services: the company owns or operates a secure building, and state or federal agencies pay out a per diem for each man, woman, and adolescent it incarcerates. The more prisoners held, and the longer they stay, the more money the company earns.

Private-prison businessmen have been turning profits in America since the early 1600s, when English entrepreneurs began shipping convicts to the Virginia settlements and selling them as servants. After Reconstruction, when labor plantations proliferated in the South, prison labor powered manufacturing in the North. In the late 1800s, convict labor leasing was encouraged by policy in more than a dozen states. San Quentin, which was built in 1852 from rock and clay by convicts held on a nearby prison ship, was initially operated as a for-profit enterprise. State and federal agencies took control of prisons starting in the 1920s, but that government-run system, made familiar by classic Hollywood films in which every guard and warden was a public employee, was a historic aberration and a model that proved incompatible with the demands of the drug wars of the late twentieth century.

In the 1980s, with prisons brimming to cruel and unusual densities, judges ordered agencies in more than two dozen states to remedy their constitutional violations. According to Christopher Petrella, a prison-policy analyst, these orders were the first step toward a gradual return to private enterprise. “Crowding litigation has historically served as a catalyst for the rapid expansion of prison capacity and thus the emergence of for-profit prison management,” Petrella told me. Faced with eliminating overcrowding while finding room for scores of new drug offenders, lawmakers warmed to the same ideas that had appealed to the British 400 years earlier.

Private prisons, which cost less and were built faster than government projects, rapidly outpaced their already booming public counterparts. In 1990, there were roughly 7,000 inmates in private facilities throughout the nation, according to the ACLU. By 2009, that number had grown to nearly 130,000, an increase of about 1,600 percent. Today, some 10 percent of the country’s total prison beds are for-profit, with rates as high as 44 percent in some states.

Since its first federal contract, in 1983, Corrections Corporation of America has grown into the fifth-largest jailer in the country. It holds 85,000 inmates in 14 million square feet of prisons spread through nineteen states and the District of Columbia. Only the federal Bureau of Prisons and three states — Texas, California, and Florida — incarcerate more people. The Geo Group, an international player with more than 78,500 beds in the United States, the United Kingdom, Australia, and South Africa, is their main domestic competition. Since 2006, Geo’s stock has nearly quadrupled in value and CCA’s has more than doubled. In 2001, total revenues for all private-prison operators worldwide were $1 billion. A little more than a decade later, the combined profits of CCA and Geo alone reached $3 billion. The two companies own or manage roughly 75 percent of the for-profit-prison beds nationwide, and along with the Utah-based Management and Training Corporation (MTC), they bring in roughly 90 percent of the partnership-corrections industry’s gross income.

“Our revenue is primarily from government entities at the federal, state and local level,” CCA writes in its shareholder report. According to Petrella, CCA’s revenue is approximately 99.2 percent government-sourced.4 These companies are more accurately thought of as outsourced government agencies.

Two years ago, both Geo and CCA legally redefined themselves as real estate investment trusts (REITs). Historically, to qualify as a REIT, a company had to prove that its revenues were wholly derived from real estate holdings. But as the Internal Revenue Service gradually loosened these requirements, prison companies, which identified themselves as landlords for the government’s criminals, were positioned for the change. CCA and Geo converted within a few months of each other and saw the same immediate benefits — exemption from the 35 percent federal corporate tax rate, cash dividends for stockholders (REITs are obligated to distribute 90 percent of earnings to shareholders), and increased stock value.

The conversion also helped the industry invent new, mutually beneficial arrangements for its government clients. In fall 2013, under court order to alleviate overcrowding, the state of California made a deal with CCA to turn the company’s for-profit federal immigration holding center in California City into a state prison. After the transition, CCA maintained ownership of (and earns rent on) the facility, an arrangement that solidified both the REIT’s primary role as landlord and the prison-guard union’s claim on jobs. “This format really addresses the principal concerns of many constituencies,” Sommer said. “If there are downside risks, they are not evident to me at this juncture.”

For major-party politicians, too, the benefits of privatization are more apparent than the risks. Democrats ride on unionized jobs. Republicans recruit corrections companies, cut department budgets, and tout the marvels of the free market. In rural America, where manufacturing is gutted, agriculture consolidated, and downtowns sit fallow, prisons do more than provide much-needed jobs. The federal census makes no distinction between the free and the jailed in its population counts, and a few thousand inmates can help a desperate district gain political clout for schools, roads, or any number of voter-pleasing projects.

The industry benefits the state in many ways, but it does not take its recession-proof profits and noncompetitive bids for granted. In 2013, CCA spent $2.7 million on forty lobbying firms in twenty-seven states and the District of Columbia “to educate federal, state, and local officials on the benefits of partnership corrections.” The company also operates a political action committee, CCA PAC, which makes political contributions to choice candidates while assuring shareholders that its decisions are made with the inmates’ best interests at heart. “As a matter of longstanding corporate policy and practice,” CCA says, it never lobbies “for or against policies or legislation that would determine the basis for an individual’s incarceration or detention.” But until 2010, CCA was a member of the American Legislative Exchange Council (ALEC). During the period of CCA’s membership, ALEC lobbied for mandatory-minimum statutes for drug crimes, California’s three-strikes law, federal immigration detention regulations, and Arizona’s Senate Bill 1070, the anti–undocumented immigration measure signed into law by Governor Jan Brewer in April 2010. (A spokesman for CCA told me that the company was a “non-voting” ALEC member “for the purpose of monitoring policy trends.”)

Meanwhile, contractual occupancy quotas — also known as capacity guarantees — set a minimum number of inmates that the government must supply to a private facility. If a government agency, be it the Arizona Department of Corrections or the Department of Homeland Security, fails to meet the minimum, it pays for the promised inmates nonetheless. Quotas accomplish two key objectives: they shift the industry’s most acute risk — a lack of inmates — away from shareholders and squarely onto the government, while also encouraging high prosecution rates, regardless of the frequency of crime. Quotas vary from state to state and prison to prison, but a 2013 study of seventy-seven state and county for-profit facilities conducted by In the Public Interest, a government-contracting watchdog group, found that 65 percent of contracts included guarantees, which ranged between 80 and 100 percent occupancy. ICE has a quota, written into federal code by bipartisan congressional assent, to maintain at least 34,000 beds for detained migrants.

Quotas are guaranteed regardless of circumstances. In the summer of 2010, three inmates escaped Arizona’s Kingman State Prison, an MTC-operated facility, with the help of a relative who threw some tools over the top of a fence. According to a report in the Arizona Republic, Kingman’s guards ignored the alarm that went off, because it had been broken and sometimes rang 200 times during a shift. Two of the escaped convicts kidnapped and murdered a retired couple driving through the area, shooting them at close range inside their RV and setting the vehicle on fire.5 After the devastating breach, the state declared Kingman dysfunctional, removed hundreds of flight-risk inmates, and suspended new arrivals. Citing the eleven months that passed before the prison was back to its guaranteed 97 percent occupancy, MTC threatened to sue the state for $10 million in lost fees. Arizona settled for $3 million.

Private-prison incentives undeniably pervert the system. “The business model they employ is perpendicular to the fundamental goals of recidivism reduction, or of criminal-justice policy,” Petrella told me. But the economic and political imperatives that empower the system reach well beyond the 8 percent of American inmates who sleep in private beds. Guard-sanctioned “gladiator schools” have encouraged inmate-on-inmate violence in public and private prisons alike. A class-action lawsuit filed last October against the Alabama Department of Corrections alleges rampant guard-on-inmate violence at the state’s maximum-security St. Clair Correctional Facility. Juvenile solitary confinement and the death penalty, including a highly publicized bungled execution in Oklahoma last year, are paid for by your tax dollars, as well. Petrella worries that “the habit of fetishizing the dysfunction of for-profits obscures larger questions about the purpose of punishment.” For the prisoner serving a twenty-year sentence for selling marijuana, it doesn’t matter who owns the prison.

Other stakeholders in the public system have found opportunities every bit as desirable as those exploited by profit-seeking companies, and public-sector interest groups — such as those that represent prosecutors, law enforcement, and prison guards — have also lobbied against reform. The California Correctional Peace Officers Association, the state’s prison-guard union, which represents some of the best-paid correctional officers in the country, helped push through the state’s three-strikes law in 1994. The law sent petty thieves to prison for decades and contributed to the state’s ongoing and unconstitutional overcrowding. The guards had been staunch opponents of private prisons, but in California City, the union essentially merged with the industry.

In early August of 2014, Geo’s stock experienced its largest price jump of the year, a 7 percent spike over two days that came on better than expected second-quarter news: tens of thousands of Latin American children had fled to the Mexican-American border.

Tobey Sommer, the SunTrust analyst, confirmed the causation. There is “an expectation emerging that the ongoing political issue of immigration and subsequent additional funding that immigration is receiving could result in more business for both companies,” he told me. Geo executives said as much during their second-quarter investor conference call on August 6, when they announced a partnership with ICE at the Karnes, Texas, civil-detention center for “housing family units as a result of the ongoing crisis along the southern border.” The Karnes facility houses mostly women and children, in rooms that, according to Geo, feature individual bathrooms and showers, televisions, and microwave ovens. School-age children at the facility, said Geo president John Hurley, “will be attending education classes on premises conducted by a certified charter school under contract by Geo.” As the crisis continued and the Department of Homeland Security announced $405 million in new funding, Hurley said that Geo was quick to offer ICE “a number of proposals to provide secure residential care.”

A formula applies to both the fiscal and political logic: More prisoners mean more dividends. The inescapable result is that American inmates exist in a country within a country, a totalitarian vassal state with a captive consumer market and little regulation. It doesn’t make much difference whether the buildings are private or public property. Profits will be extracted from every part of the prison experience.6

Consider the prison-phone industry. For inmates, especially urban felons shipped to far-off rural sites, calls to the outside are a social lifeline and a proven method for reducing recidivism. But here, too, Wall Street has identified a high-demand, low-supply commodity. Other government contractors, be they food suppliers or dentists, collect fees paid out by the state. Prison-phone companies, and the prison-wire-transfer companies that are following their model, extract revenues directly from inmates and their families. (Fifteen dollars for a fifteen-minute phone call is not uncommon.)

As with partnership corrections, profits are largely determined by contracts, but phone and money-transfer companies sweeten the deals for their public partners with profit-sharing perks. These commissions kick back anywhere from 40 to 60 percent of revenue to the contracting government agency. According to a study by Prison Legal News, a publication of the Human Rights Defense Center, about 85 percent of non-federal jails sign up for commission-added contracts, and because commissions increase in proportion to the total contract value, cash-strapped public officials are motivated to choose the most expensive contract available. Prison Legal News found that when Louisiana put out a public request for proposals for phone services in 2001, the agency stated the wish explicitly: “The state desires that the bidder’s compensation percentages . . . be as high as possible.”

In 2000, prison-phone commissions totaled more than $20 million in both New York and California. The states, along with at least seven others, have since phased out the kickbacks, and after a decade of petitions, the FCC has instituted limits on interstate call rates. But the FCC rules have not affected intrastate rates, and inmates and their families still deal with exorbitant fees. The prison-phone industry, which generated more than a billion dollars in annual revenue in 2014, is one of the brightest stars in the corrections economy.

Wall Street is paying attention, and private-equity investors have been driving successive rounds of merger activity. In 2004, prison-phone companies T-Netix and Evercom Systems merged to form Securus Technologies, a firm that in 2009 locked down a five-year, $95 million contract to supply services in twenty-five CCA facilities. But GTL, which owns about 57 percent of the prison phones nationwide, is the prize. In 2009, the company was purchased by two private-equity firms, Veritas and Goldman Sachs Direct, for $345 million. In a widely publicized Wall Street deal, they sold GTL two years later to another private-equity firm, American Securities, for $1 billion, a return of 190 percent on their investment. A year later, Securus sold for $700 million. Today, three companies — Century Link, Securus Technologies, and GTL — control about 90 percent of the prison calls in the country.

This rigged game of economic exploitation is a recurring theme in Rand Paul’s list of criminal-justice grievances. “You’ve got poor people caught up in stuff where they are fined, where they go to jail if they can’t pay the fine, then the private company that’s making money off the ankle bracelet is charging him three hundred fifty dollars a month,” Paul said. “Then you go to debtor’s prison for not paying your debt. People get trapped, and poor people are particularly trapped.”

In 2010, Geo acquired Behavioral Interventions, an electronic-monitoring company that tracks roughly 60,000 offenders nationwide and is the only federal contractor for electronic supervision of ICE-detained migrants. In many Southern states, private debt collection and probation companies work hand in glove with law enforcement to extract steady profits.

“Over time, you realize that the Pentagon and the prisons do things that the government ought to deal with,” Grover Norquist told me. “Prisons are too important to leave to the wardens. Criminal justice is too important to leave to the prosecutors. Conservatives assumed the cops and prosecutors were all good guys. Turns out that was not a safe bet.”

The power of corporate interests may be a widespread outrage in this country; dismay and disgust with the financial sector might have been the common complaint shared by the Tea Party and Occupy Wall Street. But real reform only comes when there is consensus about something being broken. As long as the machines are running in lower Manhattan, and migrant children are safer in a South Texas detention facility than in their own countries, the system thrives. The schizoid American psyche, split between corporate boosterism and anti-corporate populism, will forever war against itself.

As Eric Holder finished a six-year term as attorney general, during which he spoke out frequently about mass incarceration but left the federal government’s prison numbers much as he found them, he told a congressional sentencing commission that prison reform was a bipartisan issue that should appeal to the overlapping interests of the fiscally conservative, socially liberal American middle class. “Overreliance on incarceration is not just financially unsustainable,” he said in his testimony, “it comes with human and moral costs that are impossible to calculate.” With this, Holder offered a classic misinterpretation that betrayed a fault of perspective. He failed to consider the needs of the system itself. The American prison system isn’t broken; it’s working exactly as designed. Seven million people may find their lives constrained, but according to the metrics that make America hum, their time served is also value added. Critics who mistake mass incarceration for a failure of social justice are oblivious to a stronger governing principle: Criminal justice is a business, and business is good.