Discussed in this essay:

The Selected Letters of Langston Hughes, edited by Arnold Rampersad and David Roessel. Knopf. 480 pages. $35.

Did you ever see peaches

Growin’ on a watermelon vine?

Did you ever see peaches

On a watermelon vine?

Did you ever seen a woman

I couldn’t take for mine?

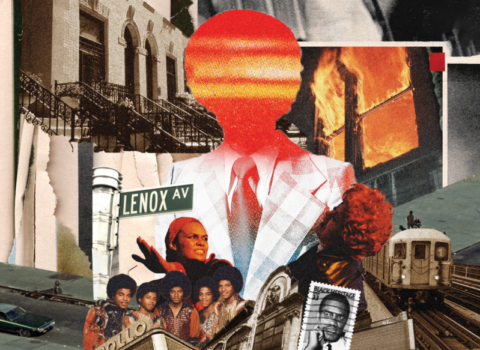

My first-grade and fourth-grade sons are fully embarrassed by Langston Hughes’s poetry, which is often in the mild dialect Paul Laurence Dunbar once called “a jingle in a broken tongue.” But for my generation, sympathy with Hughes was immediate; his poems were anthems of our childhood. “Mother to Son,” “The Negro Speaks of Rivers,” “I, Too, Sing America”: our teachers and parents, who had gone to elementary school in the 1930s and 1940s and had seen Hughes recite, knew these poems by heart, and that history imbued our own recitations with a poignant heft. When I won a scholarship to prep school, I received a paperback edition of the Hughes-edited The Poetry of the Negro from an intellectual family friend in the same way that a soldier was given a Bible before heading off to combat. Hughes was our foundation, the bedrock of our common identity, completely intertwined with our shag haircuts, David Thompson sneakers, and Swedish knits. It was impossible to separate him from twentieth-century black cultural totems, even those he had nothing to do with, like “Lift Every Voice and Sing” and Kwanzaa.

Hughes cultivated his image as the “Negro poet laureate,” as he was often referred to, as a business ploy and worked hard to nurture his career among black Americans. “I want to help build up a public (I mean a Negro public) for Negro books,” he wrote to James Weldon Johnson in 1931, while planning an expedition to black schools, churches, and lodges, “and, if I can, to carry to the young people of the South interest in, and aspiration toward, true artistic expression, and a fearless use of racial material.” During that year, Hughes found that he could indeed make a living with a primarily black audience, which was good, because he was never successful on white American terms, either aesthetically or financially (“a major career on a minor income” was his own description). He recognized early that he would probably have to live and die enmeshed in his racial identity.

“Langston Hughes,” 1942, by Carl Van Vechten © The Carl Van Vechten Trust. Courtesy Carl Van Vechten Papers, Yale Collection of American Literature, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library

Hughes got a significant boost in prestige across the color line nearly thirty years ago, when The Life of Langston Hughes, a two-volume biography, was published. The book revealed in vivid detail his extraordinary life and artistic struggles; it also had the collateral effect of elevating biographical treatments accorded African-American subjects more broadly. The author, Arnold Rampersad, and his research assistant, David Roessel, have now compiled a tasteful and well-annotated selection of Hughes’s letters. Two books of Hughes’s remarkable correspondence precede this collection: in 1990, Charles Nichols published a significant block of the letters between Hughes and his close friend Arna Bontemps, a novelist and librarian, and in 2002, Emily Bernard edited a shrewd chronicle of the literary friendship between Hughes and his patron Carl Van Vechten. The 254 letters included in Rampersad and Roessel’s The Selected Letters of Langston Hughes start in September 1921 and end in April 1967. For the most part they are addressed to only a handful of correspondents; nearly 10 percent are written to the wealthy Californian Noël Sullivan, another friend and patron. (Hughes, describing the unusual bond, told Sullivan that “to say what your friendship has meant to me would take more pages than I have ever written in any of my books.”) Together, the letters chosen by Rampersad and Roessel present a marvelous record of the euphonic as well as the discordant notes of Hughes’s twentieth-century America.

Hughes was born in Joplin, Missouri, in 1902, and was raised partially in Lawrence, Kansas, and Kansas City. He had a difficult relationship with his father, James. The opening letters of the volume show him in the unenviable position of being a very young man, precocious if not a literary prodigy, struggling to convince his hardened patriarch of the value of a life devoted to the arts. By 1921, James Hughes had already quit the United States (along with his son, whose legal name was also James) for Cuba — and later Mexico — likely on account of the intolerable racial situation. Even when Langston was accepted to Columbia University, the elder Hughes clearly believed that his son was too precious to succeed, a floundering hothouse lily at an expensive school in an expensive city. “I don’t want to burden you if you can’t keep me in school,” Hughes chirped to his father, which was followed a few months later by the offhand coda, “Columbia was interesting. Thanks for the year there.” His father may have been right about the uselessness of a freshman year in Morningside Heights: Hughes admitted to Countee Cullen, a fellow poet, that “I spent more time last spring on South Street looking at the ships than I did in the Dorms.” Langston hoped that approval from blue-chip black people might help him regain his father’s confidence. Of the writer and teacher Jessie Fauset, the literary editor of the NAACP magazine, The Crisis, Hughes wrote, “Did I tell you that Miss Fauset has been reading my poems in the New York City high schools in her lectures on modern Negro poetry?” He was pleased, he told his father, that fans of his race-proud modernist poems in New York “seem to take them seriously. Ha! Ha!” But flinty James Hughes would never regard with pleasurable significance either the poems or the poet.

In addition to ogling the boats, Langston spent his year at Columbia grooving to the musical Shuffle Along and nurturing an unrequited love for the theater that would last throughout his life. He also began discussing German, French, and Spanish musicals and plays with Alain Locke, a Howard University philosophy professor. Locke’s interest in Hughes had an obvious sexual component; what later became known as the Harlem Renaissance was fueled as much by the libidinal undercurrents as the artistic and intellectual overcurrents in the friendship shared among Hughes, Cullen, and Locke. “You are right that we have enough talent now to begin a movement,” Hughes assessed in the spring of 1923. “I wish we had some gathering place of our artists, — some little Greenwich Village of our own.” But unlike the other two talented men, who devoted themselves to classrooms and traditional forms of literary expression, Hughes was always crossing borders and surmounting orthodoxies.

Instead of becoming Locke’s petted liege in Washington, Hughes lit out for the territories in 1923, working on an Africa-bound cargo ship. On another voyage, he jumped ship and headed to Paris. He washed dishes at a Montmartre nightclub with an all-black staff, where “the jazz-band starts playing at one and we’re still serving champagne long after day-light.” He went to Italy, where he caught up on his classics with Locke, and, after the professor left, wrote the haunting, dirgelike, but uplifting “I, Too, Sing America” on the back of a letter while in Genoa.

Hughes turned from a darling black lyricist into a bluesman of the “low-down” “rough stuff” in 1925 when he planted himself in Washington, D.C. At first he prepared to attend Howard to study with Locke, but decided against it. Instead, he immersed himself in the music of Bessie Smith, Clara Smith, Ozie McPherson, and banjo-playing clog dancers. He was a bright young jitterbug having a love affair with black American life, and the next summer went “ ‘on the bum’ through the flood district to New Orleans,” a pilgrimage that Hughes anticipated would “yield some grand experiences.” By 1926, he had completed a book of poems, The Weary Blues, which included several of what would become his most famous works and which was followed the next year by another collection, Fine Clothes to the Jew. Although Hughes was now launched as a poet, he never gave up his original sort of derring-do; he was always willing to vagabond and put himself in danger, as he did in 1931, to reach the condemned boys in Scottsboro, Alabama, and in 1937, to report from Madrid during the Spanish Civil War. From this plebeian soil Hughes dug out more collections of poetry, including Let America Be America Again (1938) and Shakespeare in Harlem (1942); a novel, Not Without Laughter (1930); the short stories collected in The Ways of White Folks (1934); and plays such as Mulatto (1935), Troubled Island (1936), and Little Ham (1936).

Hughes’s huge personality comes through clearly in his letters. “I always do as I want, preferring to kill myself in my own way rather than die of boredom trying to live according to somebody else’s ‘good advice,’ ” he wrote to a friend. He had a deep sense of loyalty to people who supported him, like Fauset, who published his poem “The Negro Speaks of Rivers” in The Crisis. When Eric Walrond, a brilliant peer, disrespected Fauset in a literary review, the typically uncholeric Hughes judged Walrond “terribly childish” and said he was tempted “to punch him in the eye.”

Some of Hughes’s most interesting letters are to Claude McKay, a Jamaican writer. Though Hughes was circumspect in most of his literary communications, he shared an open camaraderie with McKay. About McKay’s book Home to Harlem, Hughes wrote, “Lord, I love the whole thing. It’s so damned real! . . . Your novel ought to give a second youth to the Negro vogue. Some said it would die this season.” His penchant for real talk spared little that was sacred to black people. In 1928, Hughes criticized Tuskegee University, which McKay had attended while living in the United States: “Do you remember . . . the nice Negroes living like parasites on the body of a dead dream?” Hughes maintained his opinion on Tuskegee throughout his life; the year Ralph Ellison enrolled as a student there, Hughes called it “a huge trade school going dead.” Although he felt a strong bond with black American porters, mop wringers, hairdressers, and cooks, he opposed the narrow confines of the black elite, the mimes of a white world that forcibly excluded them. When Ezra Pound wrote to him about the possibility of a black school hiring a trained African historian who knew the culture of ancient Benin, Hughes complained that “Howard and Fisk . . . are trying desperately to become little Harvards” and that the winds of modernism and cultural relativism had not reached these “highly religious, highly imitative” schools, which were “mostly controlled by white gentlemen.”

Hughes did not limit his criticisms to the black institutions, or people, of the South. When he came to the North, he noted the bizarre excesses of the place in a humorous observation about the oldest profession:

In Boston I didn’t go anear Harvard . . . but I met a colored lady who looked like she possessed six degrees, wore nose glasses and all, — and had been in jail eighteen times and in the pen once for robbing her clients, — Chinese laundrymen and white clerks, — but she was still operating undaunted. I never saw so dignified a daughter of joy before, but she said she had always worn pince-nez.

Throughout his career, Hughes resisted becoming a hack writer, or jobber, and he often turned down worthy assignments to uphold his integrity. When the famed educator Mary McLeod Bethune asked him for ghostwriting advice for her autobiography in 1932, he determined that

a life such as yours connected so closely with the general problems of Negro education would, if I wrote about it directly and personally, demand from me, I feel, a critical treatment that, while not in any way touching your own splendid position, might hold up to too unpleasant a criticism our entire American system of philanthropic and missionary education for the Negro.

Hughes saw the class cleavage in education for the threat that it was. After the Harlem Riot of 1943, which he missed while visiting Yaddo as the artist colony’s first black guest, he chuckled at the condemnation issued by the tony Harlemites of the Sugar Hill neighborhood near City College: “The better class Negroes are all mad at the low class ones for disturbing their peace. I gather the mob was most uncouth — and Sugar Hill is shamed!” Why were they so mad? “Laundries and pawn shops looted, they suffered almost as much as the white folks.” Hughes’s capacity to poke fun at his own class kept him ever a man of the people, one who was welcome all his life on the streets and in the bars and nightclubs of black America.

In the first volume of The Life of Langston Hughes, Rampersad attempted to explain his subject’s deep devotion to his racial identity. Describing Hughes’s fall from the grace of a wealthy patron, Charlotte Osgood Mason, Rampersad wrote, “Now Godmother had banished him, just as his father and mother had done in inflicting the great, unhealable wound of his life.” Rampersad concluded that “only his race, black and itself abused, never banished or abandoned.” In his introduction to Selected Letters, Rampersad doubles down on the thesis:

Hughes evidently fell in love with Mrs. Mason, as a son loves his mother. . . . Cast off, he pleaded desperately for reinstatement. . . . But Godmother never changed her mind. Broken, Hughes spent months recovering from this crisis — if indeed he ever recovered fully from it.

As evidence, Rampersad and Roessel include five sensational draft letters that Hughes devoted to Mason in 1929 and 1930. Hughes worked to present himself as Mason desired him: part exotic primitive, part chameleon playtoy. “I am sorry that I have not changed rapidly enough into what you would have me be,” he apologized to her in one communiqué. “You must not let me hurt you again. I know well that I am dull and slow.”

Even if Hughes’s words were genuine, and not a maneuver in a contest for Mason’s resources — with Locke (who’d become a nemesis by 1929) and Zora Neale Hurston (a nemesis by 1931) — Rampersad’s argument that Hughes never got over the break remains controversial. It is hard to accept that the “Negro poet laureate” was forever emotionally bound to a rich, elderly, dilettante-Africanist patron. Nor was it Mason’s withdrawal alone that soured the end of the 1920s for Hughes. He noted the ways in which the avaricious, mercilessly cretinizing engine of popular culture was keen to exploit African-American content:

Awfully bad colored shows are being put on Broadway every week or so now. . . . Some of the colored victrola records are unbearably vulgar, too. Not even funny or half-sad anymore. Very bad, moronish, and, I’m afraid, largely Jewish business men are exploiting Negro things for all they’re worth.

Beyond a few playful letters to the beautiful Afro-Chinese ballerina Sylvia Chen, evidence of Hughes’s sexuality is not on display. The Hughes presented here seems abnormally fearful of sex; his fear may have had complicated sources in the age before reliable birth control and treatments for sexually transmitted diseases. But he seems to have worried that the women he encountered wanted to consume him like a treat, a sugar daddy, or a tonic. He also had a coy, teasing relationship with his mother, Carrie, to whom he signed off a letter, “Lots of love to you. One kiss.”

In the recent book My Dear Boy, John Edgar Tidwell and Carmaletta Williams collect Carrie Hughes’s letters to Langston and offer the fascinating argument that much of Hughes’s poetry of the 1920s and 1930s was written in response to her. Certainly, Carrie competed with her son for professional acclaim (she hoped for success in show business), and their relationship does seem to have shaped his basic sexual responses to both women and men. Hughes may even have been partly in love with her; her death left the poet wounded in ways he was disinclined to show.

In October 1935, Hughes learned that Carrie had cancer — it would eventually kill her — and that she needed expensive radium treatments. She was unable to rely on public assistance, so “the only thing to do,” he wrote Sullivan, “is pay for the operation myself.” But Hughes could not afford the medicine because the producer of his play Mulatto, which was doing well on Broadway, aggressively avoided paying royalties. Hughes was arguably the most articulate writer of his generation; he was well known and well traveled and putatively affluent — but he was nevertheless powerless to ease his mother’s suffering.

In 1936, Hughes was in Chicago visiting a girl whose father had been lynched in front of her during the Chicago Race Riot of 1919, when white mobs had attacked black neighborhoods in a deadly spree. He observed that life for blacks in the North was, in many ways, a step down from that in the South. “Chicago is still a savage and dangerous city,” he wrote. “It’s a kind of American Shanghai.” Anticipating the fiction of Richard Wright, who would become a friend in the next decade, Hughes described the decline of American cities in the early twentieth century:

Almost everybody seems to have been held up and robbed at least once. . . . 85% of the Negroes are on relief. And there are whole apartment houses packed with people who haven’t paid rent for months, and the landlords letting the houses go to rack and ruin, so that they look like nothing you ever saw inside and out. . . . Kids rove the streets in bands at dusk snatching women’s pocketbooks, so people are even afraid of children.

By the middle of the 1930s, Hughes had clearly already espied for urban black migrants the “dream deferred,” his famously dim characterization of black hope that he would record in the tart poem “Harlem” in 1951.

Hughes was a courageous man, even when it was his own hind parts crisping at the fire. In 1934, when Esquire was brand-new, the magazine waffled over whether to print a “high yaller” story by Hughes that described the erotic fetish that many powerful white men had for black chorus girls. Hughes expressed delight to Blanche Knopf, his book publisher, that a “full page of letters” appeared in the magazine evaluating the story. But the dissenting voices were not playful at all: Hughes was accused of fomenting race riots like the one that had recently occurred in Tulsa, Oklahoma, where, according to a letter-writer, “it took the city incinerator days to burn the black bodies.” “Don’t you think having the only nigger in Congress is enough of an embarrassment to the administration without Chicago” — where Esquire was published — “starting something that it may cost men and millions to stop?” wrote the Oklahoma bigot. When the bone-deep neo-Confederates Allen Tate and John Gould Fletcher defended the Scottsboro Trial death sentences (“If a white woman is prepared to swear that a Negro has either raped or attempted to rape her, we see to it that the Negro is executed,” Fletcher wrote in The Nation), Hughes was ready for a confrontation. He suggested that it would be amusing for the Knopf publicity department to rile the Rebs further by sending them his new book, The Ways of White Folk. Hughes later summed up the pickle by writing that “southern intellectuals are in a pretty sorry boat. Certainly they are crowding Hitler for elbow room.”

Blanche and Alfred A. Knopf were Carl Van Vechten’s friends, and Hughes was pleased to have his books with their lustrous house, but it seems that they published him only grudgingly. When Hughes was polishing his elegantly unassuming autobiography, The Big Sea, he had to appeal earnestly to Blanche, who thought Hughes’s list of notable blacks unnecessary:

One could not write about life in Negro Washington without including the names I mention therein and who are nationally known to most colored people and who are very much a part of the literary and social life of colored Washington — which is, as I point out, a segregated life. I mention this so that you won’t think they’re being included as a “courtesy gesture,” they being as much a part of Negro life as Dorothy Parker would be if a white writer were writing of literary life in New York.

Blanche would later reject outright Hughes’s poetry collection Montage of a Dream Deferred.

Hughes did not always conceal the incredible tension of working under this kind of arrangement. During the economic collapse of the 1930s, he wrote several poems that emphasized American hypocrisy and ungenerosity, such as “Advertisement for the Waldorf Astoria” and “Goodbye Christ.” Van Vechten, who lived off an inheritance, attempted to warn Hughes away from this brand of radical verse, which would have a second life in the 1940s and 1950s, when Hughes was targeted by religious and political right-wingers. “About the Waldorf, I don’t agree with you,” Hughes responded.

At the time that I wrote the poem it was one of the best American symbols of too much as against too little. I believe that you yourself told me that the dining room was so crowded that first week that folks couldn’t get in to eat $10.00 dinners. And not many blocks away the bread lines I saw were so long that other folks couldn’t reach the soup kitchens for a plate of free and watery soup.

In fact, Hughes’s feelings about the situation were stronger than that. While he was visiting the Soviet Union in 1933, he mused, “I don’t even know why I am coming back. I’ve never lived better than here, or sold more work for actual cash, even if it is not changeable in capitalistic lands.” “Really, Moscow must be a paradise compared to New York or Chicago now,” he intoned. “At least everybody has something to eat here.” By 1947, Hughes was in full self-exculpatory mode, writing to an editor at Negro Year Book to assert, as he would repeatedly over the next half-dozen years, “I have never been a member of the Communist Party.”

Hughes did, however, keep questions of social and economic injustice at the center of his work. By the early 1940s, he had added a regular newspaper column to his already massive oeuvre, but his income-tax levy still left him “ruined and broke in both spirit and finance.” When asked about his response to the escalating anti-Communist purge of artists in the late 1940s, Hughes reflected on the situation with rare bitterness. “The publication of my name in RED CHANNELS has not affected my employment in TV or radio. Being colored I received no offers of employment in these before RED CHANNELS appeared, and have had none since — so it hasn’t affected me at all.” By 1948 Hughes’s profile had fallen so low that when the writer Arthur Koestler lectured at the Los Angeles Philharmonic, Koestler could erroneously report that Hughes had been “broke and hungry” and in the Communist Party in Soviet Asia in 1932, and was by then also dead. Alive and smiling, Hughes was sitting in the audience.

In the lead-up to the McCarthy hearings, Hughes found himself vulnerable because of his race and his politics. “Without your able help,” he wrote in 1953 to Frank Reeves, his black attorney, “and kind considerate, patient and wise counsel, I would have been a lost ball in the high weeds or, to mix metaphors, a dead duck among the cherry blossoms.” In 1954, this self-described “literary sharecropper tied to a publisher’s plantation” owed his stenographer money and still had to scurry to Van Vechten for a hundred dollars to pay his debts. Luckily his dentist, “being a patron of the arts,” forgave his debt and “never sends me a bill.”

By 1960, Hughes feared that he had grown “NAACP-ish,” by which he meant “over-sensitive racially,” but he remained in constant battle against the commercial panderers of black culture. As he watched the stereotypes change from comic to thug and back again, he put his hopes in “the boomerang that will set back the setter-backers!” Hughes’s letters to his radical black friends who had a stake in even stronger political conversations — among them Horace Cayton, John P. Davis, Ralph Ellison, Loren Miller, Louise Thompson Patterson, Matt Crawford, and William Patterson — will, one hopes, appear in published form at a later date. (Some of this material is forthcoming in the book Letters from Langston: From the Harlem Renaissance to the Red Scare and Beyond, edited by Evelyn Louise Crawford and MaryLouise Patterson, the daughters of four of Hughes’s friends.) But it’s a tribute to his integrity and the vitality of his craft that so much of his work remains effortlessly current now. The Hughes revealed in the letters, so slyly resolute and patient in his commitment to bending art in the direction of justice, is a powerful reminder of the resources necessary to remedy the ills — from Ferguson to Cleveland to Staten Island — of our own time.

Before he died, of prostate cancer, in 1967, Hughes opened the doors for more than one writer whose later reputation, at least in America’s ivory towers, outstripped his own. Ralph Ellison began as a devoted friend of Hughes’s but, as the relationship deepened, Ellison began to sense the lack of an intellectual dimension in Hughes’s craft and became disillusioned. Always modest, Hughes amicably endured the young lions who benefited from his friendship and his path-blazing example. He had, he wrote in 1958, “lived longer than any other known Negro solely on writing — from 1925 to now without a regular job!!!!! (Besides fighting the Race Problem.)”

The letters to and about James Baldwin, whose published criticism for decades upbraided Hughes and Richard Wright, are a case in point. The Selected Letters includes two letters drafted to Baldwin (one other is mentioned in a footnote), and they signal the testy relationship between Baldwin and the older man, who had settled permanently in “mighty whooping and hollering” Harlem in 1942, quite close to the time that Baldwin escaped it. Within a dense vernacular, Hughes poked fun at Baldwin’s distance from black folkways:

Man, after reading

your piece in “Per-

spectives” I didn’t

expect you to write

such a colored book

—without the u.

Almost ten years later, Hughes read Baldwin’s collection of essays Nobody Knows My Name, and wrote to applaud Baldwin, who was by then the most famous black writer of the 1960s, for becoming a “cullud sage — whose hair, once processed, seems to be reverting.” Hughes was extraordinary for so many reasons, but especially for his legacy as an artist who stood for blackness and beauty and the poor, not least when they were all the same despised thing. He once said about Amiri Baraka (then called LeRoi Jones), a writer who, like Ellison and Baldwin, stood on Langston’s shoulders to grasp the acclaim that Hughes never received, “He doesn’t like my work — which I don’t mind. I like his.”